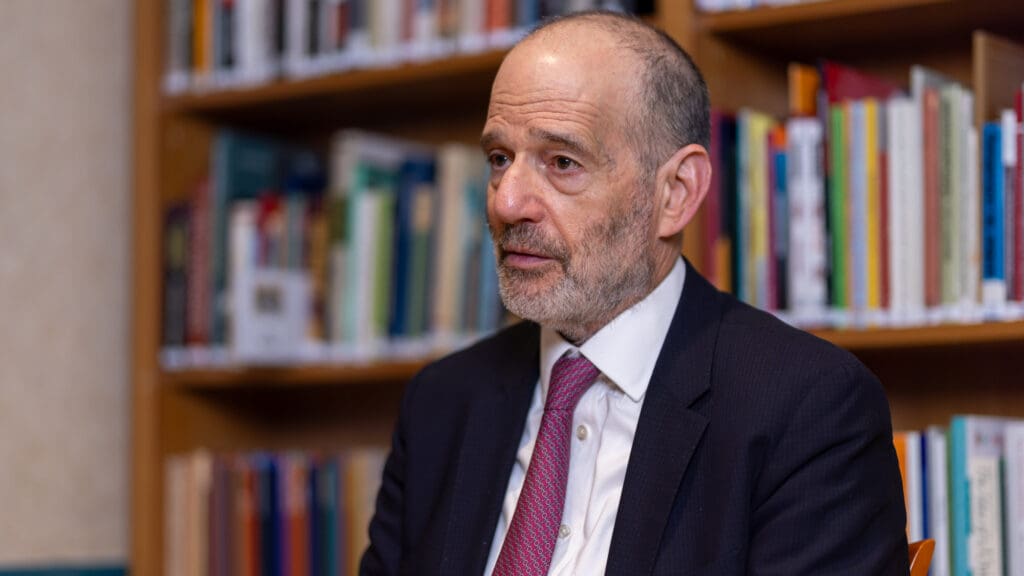

Barry Strauss is a Professor of History and Classics in Humanistic Studies at Cornell University and the Corliss Page Dean Visiting Fellow at the Hoover Institution. His books have been translated into twenty languages. He is co-founder and Director of Cornell’s Program on Freedom and Free Societies. He completed his Doctorate at Yale University and his Bachelor’s degree at Cornell. During the MCC Summit on Education, Hungarian Conservative had a chance to sit down with him to talk about philosophy and AI usage in the classroom and its incorporation into education.

***

In your opinion, what is the role of philosophy in education regarding critical thinking and building worldviews?

I think we begin with Socrates. And with Socrates’ famous statement that the unexamined life is not worth living. And so we want to get our students to examine their lives, and to rigorously question all the things that they believe in. Now, that being said, we want students to start from a foundation of faith, which we as teachers are not going to give them, that’s something that they’re going to have, they’re going to bring to the table. But once they have that bedrock foundation, we want them to question everything else, and ask what to do. And that’s the purpose of education. That’s the purpose particularly of university education. So I would say that’s when we start.

And then we want to take students and shape them into people who believe in the Western tradition, who know what the Western tradition is, actually, they don’t have to believe in it, they have to know what it is. And they have to use it as a foundation to start from if they want to question or want to challenge it. They need to know what this tradition is. So we’ve got to do that. And we also want to prepare them to be citizens. We want them to know what their responsibility is to the community and what it means to be a citizen. We don’t want them to simply have a passive attitude towards us. We want them to be informed, we want them to be engaged; they don’t have to be activists, they just have to think they have to be thoughtful about issues.

You mentioned faith as a foundation. If someone is on the edge between two avenues of faith, do you believe that teachers should or can influence them?

I don’t think teachers should influence students directly. I don’t think it’s the teachers who say, I want to convert you to this or that. But I think teachers can play a very good role by setting an example. You know, if a teacher makes it clear that he or she is a person of faith. And I think the students will take that seriously. I think students and all people always take more seriously something that’s done by example; you have to lead by example. So I think that it’s important. That being said, particularly in a university setting, there will be teachers who are atheists and don’t have faith. And that should be allowed, because we want universities to be places of free thinkers. But I think that in general for society, it’s much better if students start with some faith.

Do you believe that philosophy as a subject can enhance a student’s understanding of complex ethical and moral issues?

Yes, to a degree. I’m not a philosopher, I’m a historian. So I’m somewhat on the sidelines. But yes, I think students need to learn to think rigorously, and to have a sense of what the basic questions of philosophy are. And that can help them develop the scope, the skills of thinking that you need to make decisions about complex ethical and moral issues.

That being said, philosophy can only go so far. Philosophy is proudly impractical. And I think it should be impractical, because it needs to abstract itself from the practicality to think of the framework of ideas. Also, I really do think there are issues in life that have to be answered by the heart and have to be answered by speaking to emotions and to emotional sense. God comes more from the heart than it does from the head. I think there’s a lot of truth in that.

Do you think that educators, teachers, should try to include philosophy in almost every subject that they teach?

Yes, I mean, to a degree. So in my own field, which is history, I think that you need to have a framework of how you think human beings behave, and what you think history is all about, what you think matters. I mean, in crude terms, you’d have to decide if you’re a materialist or not. Or if you think there are other things that move human beings. I think it’d be very hard to be a good historian without having some sense, knowledge, and intimate knowledge of the Western philosophical tradition. I think you’re kidding yourself if you believe you can do without it.

That being said, that philosophical tradition doesn’t have to come to the centre. But I think it has to be in the background, at least. It’s also difficult to teach students who don’t know anything about the philosophical tradition. I’ve often been frustrated by the gaps in students’ knowledge. I mean, they don’t have a basic idea of what Plato said. Sometimes they don’t have an idea of what Plato said what Aristotle said. It’s very difficult to understand in America if you haven’t read John Locke, and you don’t know what John Locke is all about.

A few years ago, I was teaching and I had a graduate student assistant, and we were talking about the origins of democracy in ancient Greece, and I had referred to Pericles. And I said, you know, in many ways, it’s echoed in Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, and I looked at him and he said, ‘I’ve never read the Gettysburg Address.’ I was really appalled. I said to him, ‘Oh, are you Canadian?’ He answered: ‘No. I’m from New Jersey’, and I said: ‘You better go read it.’ Also, it seems our students are ignorant of the Bible, too.

In your experience, do students influence each other when it comes to philosophical thinking, or do they recommend reading philosophers to others?

Yeah, let me just say as a preface, although I’ve said some harsh things about students, I think our students are very good. They’re very bright, and very, very motivated. That being said, do they read philosophers? I doubt it. Maybe those who have taken philosophy classes, but they read ‘philosophy’, this sort of stuff you find on the internet. That’s part of popular culture. And yes, I’m sure they influence each other to that degree. Maybe some of them read philosophers, and maybe they have late-night conversations about philosophy or nature.

When do you think it’s best to introduce philosophy to students? As soon as they start to learn history, or later in their studies?

I think there’s room for it in high school, in a limited way, but I think it’s mostly a matter for university discourse.

What challenges or barriers are there that you can think of that prevent the introduction of philosophy into the classroom?

Well, you know, there’s a bias against the humanities in American higher education because it’s considered to be impractical. And for the progressives, the humanities are all about dead white males: they stand in the way of equality or equity for minorities, for the dispossessed, and so forth. So that’s one obstacle.

The second obstacle is that a lot of people don’t want to do it. Don’t want to do it because it’s hard. And even once you take it seriously, it’s difficult. But the other thing is, I think most people don’t really want to question their basic assumptions. And I think that’s a big difference between college students today and college students fifty years ago when I went to university. Back then the basic idea was that you would challenge everything and question authority. And that was part of the rite of passage of the university career. Nowadays, students seem to be much more focused, driven, ambitious, focused on success, focused on leveraging the university degree to build a career. That’s not a bad thing in and of itself, but they’ve thrown away the baby with the bathwater, throwing away the good. So we need to come back to that.

Do you think that debates in classrooms, organized debates about philosophy would be beneficial at universities?

Yes, I mean, we want, you know, the buzzword that is used on the right is intellectual diversity. That’s not my favourite term. Because I think diversity is not my favourite term. But I think debate, give and take discussion, intellectual wrestling, that sort of thing is so important to academic freedom and to what universities have to do. By the same token, we want students to be civil, as you say, we don’t want the debate to be shouting, and we want it to be respectful. And we want to educate students and show them what academics are supposed to do, but the academic life is all about the life of the mind, as we used to call it. That just seems like such a quaint term nowadays.

AI and ChatGPT are defining a lot of issues right now. What is your experience with it, are your students using it to ‘cheat’?

AI really hit the scene, maybe last spring, I guess. And so I wasn’t teaching then. And as I prepared to teach in the fall, I did some research on it. I took my short essays that I had to grade the previous autumn, and I fed them into AI and I was horrified at the results. It wrote good essays within a minute, 60 seconds. So I realized I can’t give these assignments anymore. So in one of my classes, for the first time ever, in all my years of teaching, I didn’t have any essays. I had them do oral presentations, and I asked them about what they were doing in the presentations, sort of like an informal oral exam. I think that worked. All right, it was satisfactory. But I think in the long term, it’s not a solution, because you want students to be able to learn how to write. So, I mean, a limited degree of AI is helpful. When you’re using a grammar app to correct your grammar, that’s okay. It’s not great, because the problem with doing that sort of thing is that you don’t master it yourself, you’re dependent on someone else. For instance, nowadays, when you learn a foreign language, you use an app and basically cheat. One of the things I always hated about learning foreign languages is learning irregular verbs. Well, nowadays, you don’t have to do that, because the app will do it for you. But that’s terrible, because you’re not really going to learn the language. We know that AI is doing awful things in terms of social media. Just the recent scandal about Google Gemini and the images that it created.

I’m concerned that young people aren’t going to learn how to do research anymore. And this is going to lead to the devaluation of writing even more. I’ve seen some educators who should know better say, well, AI is not a problem. You just use it to write a rough draft. And I think if you’re using it to write a rough draft, that’s more than half the work of the essay, you’re just polishing it, and surely you’ll use AI again to polish it and then one way or another, the researcher is just getting the information, and they receive an A without ever going into a library, or even googling. I think it’s a disaster. I think tt should be banned. But I don’t see how you could do that. And then that would also presuppose that universities took the honour code seriously. But that wouldn’t be possible because society doesn’t take honour seriously. So, I mean, we have an honour code at my university, but it’s not exactly enforced. These things went out of fashion in the 1960s.

You mentioned oral exams and presentations. With AI closing in, are exams more important than ever?

Yes, they are, you know, written exams, except for the minor problem that young people don’t have good penmanship anymore, because they don’t really learn that so much. Yes, written exams are very important and oral exams are very important as well. Because unfortunately, you can’t really trust things where they can use a computer because they can get the computer to write it for them. It’s really sad, because AI can be very useful. I’m told that there are all kinds of medical uses that can detect diseases earlier. And that will make a big difference.

But it’s being abused now in the humanities and the social sciences, being abused in education. And for this, we need leadership from the top. I mean, the message we’re often getting is that you want to encourage students to use AI because they’re going to need it in their jobs. And to this, I say no.

Read more interviews from the Summit: