This article was published in Vol. 3 No. 1 of the print edition.

Ken Kersch Interviewed by Lénárd Sándor

Ken Kersch is professor of political science at Boston College. His research focuses on American political and constitutional developments, American political thought, and the politics of courts. Kersch is the author of five books, including American Political Thought: An Invitation (Polity, 2021) and Conservatives and the Constitution: Imagining Constitutional Restoration in the Heyday of American Liberalism (Cambridge 2019), as well as many articles in academic, intellectual, and popular journals. Professor Kersch received his BA from Williams College, his JD from Northwestern University, and his PhD in Government from Cornell University.

***

The Declaration of Independence is said to be the creedal document of the United States that provided a philosophy American governance and society has been relying on ever since. What has been the role of the Declaration in American political discourse and what was the approach of conservatives in the first half of American history?

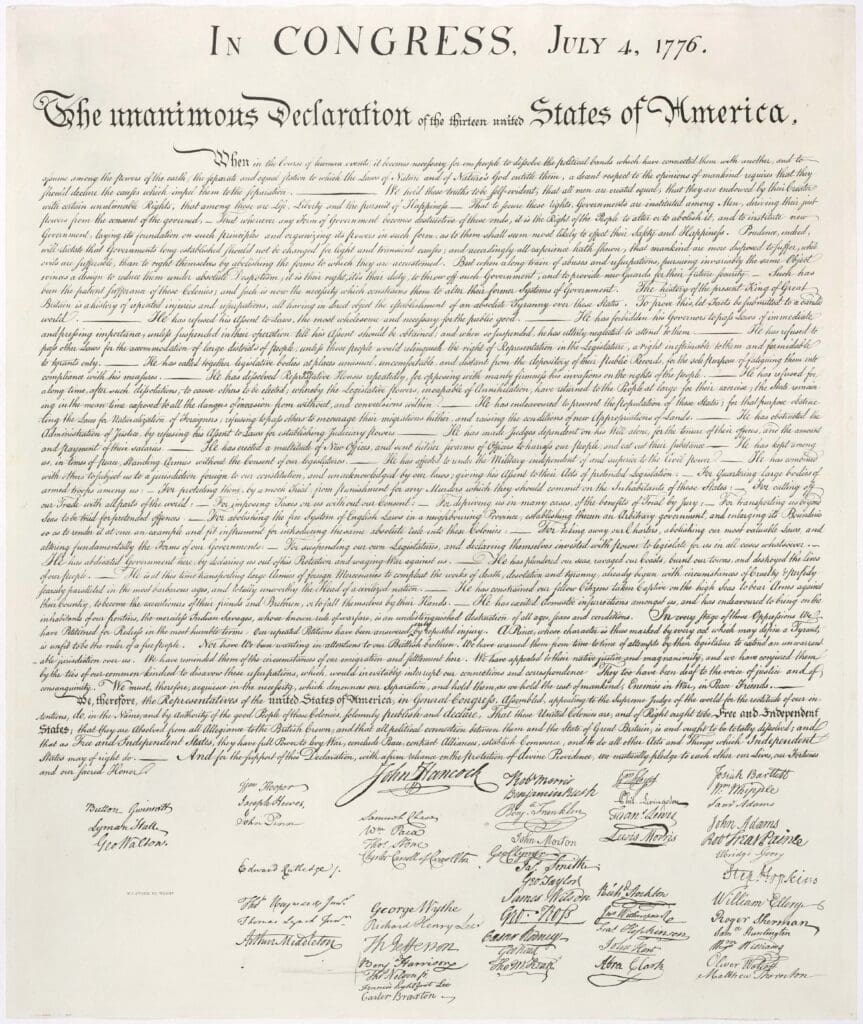

The Declaration of Independence has long been held up as creedal for a number of reasons. First, with pride and verve it announces the cutting of ties with a colonial ruler and the establishment of a new nation—co-equal to the other great sovereign nations of the world. Second, in succinct, stirring language it sets out a daringly egalitarian foundational premise: that ‘all men are created equal’. Third, in a boldly democratic spirit, it announces that this new nation is being created by the American people themselves. And, fourth, it declares that the new nation is being created by its people to protect the fundamental, pre-political natural rights with which they were ‘endowed by their Creator’—the rights to ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’.

While it drew directly from John Locke, this is nevertheless a major statement concerning the origins, theory, and nature of government. It has, moreover, proved of immense historical significance. Americans from 1776 on have enlisted the Declaration’s principles in a dizzying array of celebrations, causes, and appeals involving national independence, popular rule, and the promotion and advancement of liberty and equality. The abolitionist opponents of chattel slavery were among the most prominent to enlist the Declaration as a creedal document, arguing that the toleration of human bondage, as countenanced by the Constitution, amounted to a betrayal of the nation’s founding principles. Ever since, Americans across the political spectrum—left, right, and centre—have appealed to the principles of the Declaration to provide ballast for their causes in popular politics.

It is anachronistic to speak of ‘conservatives’ in the first half of American history. Yes, conservatives and conservatism have featured in American political life from the beginning. The problem is that the history of American conservatism does not map onto contemporary ideological templates. Conservatism in its most fundamental (traditionalist) form evinces a belief in hierarchy and authority, a suspicion of, if not outright antagonism towards, democracy, and a preference for the rooted and established, and the collective and communal, over the changing, the abstract, and the individual. It is also a defender of transcendent and anchoring moral foundations. The Declaration of Independence sits very uneasily with all of that. It is, in many respects, an Enlightenment document. Many early conservatives like John Adams declared the principle that ‘all men are created equal’ to be demonstrably false. Most early conservatives, including the Federalist founders, emphasized the distance between the Declaration’s claims of ultimate popular sovereignty and what they characterized as the more radical claims of democracy, which they took to be a threat to the protection of the rights that the Declaration was meant to protect. It is complicated.

What set the stage for the so-called ‘Declarationism’ and what does it mean in constitutional interpretation? What has been the role of the ‘natural law’ and ‘natural rights’ traditions in regards to the intellectual rise of the conservative movement? What were the stakes of the ‘Lincoln–Douglas debates’ from this perspective?

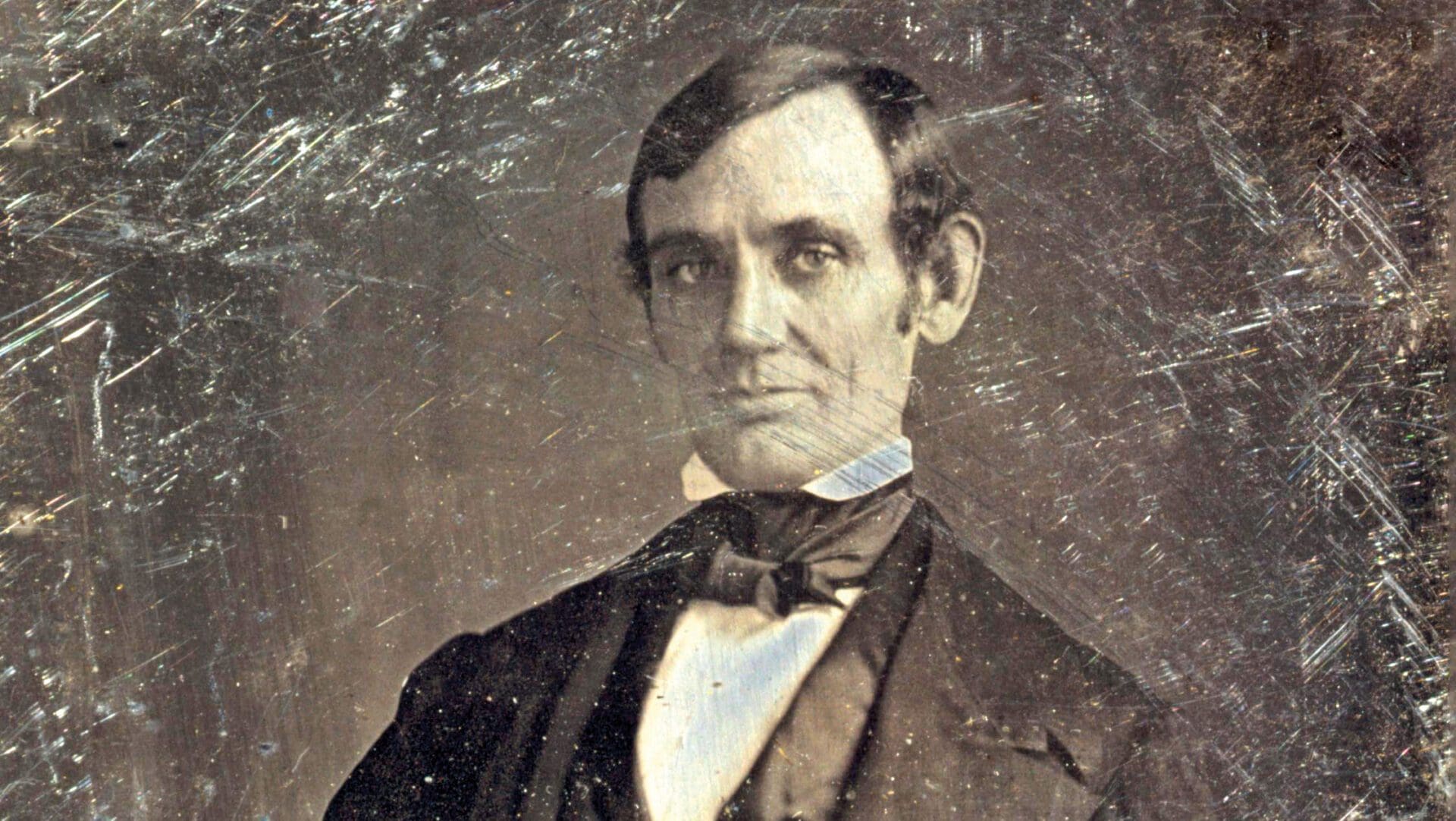

What I have called ‘Declarationism’—the decision by some modern conservatives to root their political ideology in the ‘teaching’ of the Declaration of Independence—is a relatively recent development. In a sense its roots go back to Lincoln and one strain of abolitionism advanced by Frederick Douglass. Both argued that the Founding had been marred by slavery, an affront to the Declaration’s insistence upon human equality and the commitment to natural rights. In his US Senate campaign debates with Stephen Douglas, Lincoln argued that these rights were guaranteed by all legitimate governments, and should not be subject, as concerned the admission of new states, as Douglas contended, to popular vote.

Lincoln spoke and wrote extensively on the relationship between the principles of the Declaration and the fundamental law of the Constitution, arguing that the latter had been intended to implement the principles of the former. In the mid-twentieth century, the Straussian political philosopher Harry V. Jaffa began systematically arguing that Lincoln’s understanding of the Declaration at the time of the slavery controversy was the true and best understanding of the American constitutional and political system. Jaffa added that Stephen Douglas’s popular sovereignty understanding was false, and a betrayal of ‘the American Proposition’ concerning the equality of natural rights.

But this was not a purely historical argument. Reading American history through the prism of Leo Strauss’s Natural Right and History (1953), Jaffa argued that Stephen Douglas’s view was, at its core, positivistic, relativistic, historicist, and ultimately nihilist. As such, it was an American progenitor of Nazism and Bolshevism. Jaffa and his Claremont students and their progeny, moreover, went on to argue that there was a direct line of intellectual continuity in this regard stretching from the defenders of slavery to the Nazis to contemporary American progressives—and, hence, the contemporary liberal Democratic Party.

Before Jaffa, many American conservatives had a low opinion of Lincoln. Lincoln, for instance, does not appear in Russell Kirk’s The Conservative Mind (1953), a landmark conservative movement compendium of conservative thinkers. Many traditionalist conservatives denounced Lincoln as a radical egalitarian. Libertarians denounced Lincoln as having betrayed the Founder’s Constitution by radically centralizing American government, abusing executive power, and violating individual rights.

What challenges did the conservative movement face after the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, especially in the post-war period? How did the liberal theory change the philosophy and governmental arrangement of the country?

Many conservatives accused FDR of having destroyed constitutional government in the US. Only a small ‘remnant’ of conservatives, they said, remained to keep the flame of liberty and constitutional government alive. The problem was that FDR was immensely popular. Breaking with tradition (and prompting the 22nd Amendment (1951)), he served nearly four full terms. He successfully led the US through the unprecedented twin crises of the Great Depression and the Second World War. These successes established Roosevelt’s Democratic Party programmes and policies for generations as the new baseline for American government.

New Deal liberalism was so popular that even many Republicans supported the core of the Roosevelt agenda, which included the nationalization of politics, programmatic executive leadership, and a proactively policy-oriented, problem-focused administrative and social welfare state. This meant that old-school conservatives were actually out of step with both parties. Their challenge would be to find a way back to political power, and to re-establish credibility for their ideas.

What was the philosophy behind the New Deal?

The New Deal theory of government was that constitutional limits on government power concerning economic regulation and social welfare programmes should be understood flexibly and pragmatically to advance the public interest. Government is a tool that should be creatively leveraged to help the common person, including the poor, the vulnerable, and the working class, by checking concentrations of economic power. The economy should be actively regulated to advance the common good. Moreover, FDR held that the national government had a special, enhanced role to play in solving national problems. Over time, liberal Democrats became strong defenders of individual liberties concerning the freedom of speech and press, and also of the procedural rights of criminal defendants, and champions of an egalitarian programme for civil rights. Opponents of these in time migrated towards a transformed and revitalized movement, the conservative Republican Party.

What was the role of John Courtney Murray S. J. in reconciling the country’s founding principles and constitutional institutions with the requirements of the Roman Catholic faith and in a larger sense with Christian theology and conservative thinking?

A Jesuit theologian, Murray was widely known in the mid-twentieth century US, although, even then, he spoke mostly to American Catholics. At the time, Catholics were enjoying a cultural moment in a largely Protestant country. The Catholic political-theological tradition was long defined by its anti-liberalism and anti-modernism—by its opposition to democracy, religious liberty, church–state separation, and rights-based individualism. This was a problem in the American context especially, where, at least as far as official doctrine was concerned, it raised questions about whether good Catholics could ever be good Americans. Murray was writing at a high point of American Catholic assimilation, on the eve of the election of John F. Kennedy as the US’s first Catholic president. He directly addressed that question in WeHoldThese Truths: Catholic Reflections on the American Proposition (1960).

Murray was then working on two fronts. Within the church itself, he was an architect of the modernizing Vatican II reforms. For the broader American audience, Murray wrote We Hold These Truths, a sophisticated work of constitutional and political theory that argued that not only could good Catholics be good Americans but that, in a sense, their adherence to a natural law tradition made them the most grounded of all Americans. His argument rested upon his reading of the Declaration of Independence as the ‘rock’ upon which the nation stood. From a Catholic perspective, Murray argued the foundational nature of the Declaration reflected an American national commitment to the same principles of natural law that Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) had distilled in Summa Theologica (published in 1485).

The liberal theory and the liberal reading of the Constitution managed to dominate and use the language of rights for the past seventy years or so. How did the conservative movement respond to this phenomenon? What is the role of ‘originalism’ as well as the ‘originalist interpretation’ of the Constitution in countering the liberal dominance? How do you see the recent shift in constitutional interpretation?

It is important to distinguish between the conservative legal movement and conservative constitutionalism in party and social movement politics, and conservative intellectual life. These worlds are related, but their relationship has altered over time in complicated ways.

The conservative legal movement emerged from legal academia on the eve of the Reagan administration. Beginning in the early 1970s, law professors like Robert Bork at Yale, Antonin Scalia at the University of Chicago, and Raoul Berger at Harvard began advancing ‘originalist’ arguments that targeted a liberal activist judiciary that had by then reached an apotheosis of power and influence. Nineteen seventies originalism was actually an intervention in legal academic constitutional theory debates that dated back to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The focal controversy back then was over an ostensibly politicized ‘conservative’ judiciary that was said to be thwarting democratically elected legislatures from enacting progressive labour regulations, as well as restrictions on concentrations of economic power. The progressive argument at the time was that, unless there was a clear constitutional violation, an appropriately ‘apolitical’ judge should defer to the democratically elected legislatures (and, in time, to the expert opinions made by administrative agencies). This was an argument for deference and judicial restraint. The theories of Bork, Scalia, Berger, and others—soon to be taken up by the young conservative law students at Yale and Chicago who formed The Federalist Society (1982), and championed by President Reagan’s close adviser and Attorney General Edwin Meese—essentially adopted the early twentieth-century progressive argument concerning democracy and deference to legislatures, and enlisted it in opposing what they considered to be the ‘politicized’ liberal judiciary of the Warren Court of the 1950s and 1960s. They used originalism because it promised to de-politicize the judiciary by calling for restraint to advance the power of legislatures.

What has been the stance of conservative intellectuals on the Constitution?

Conservatives in the party, the movement, and intellectual life outside the law schools had the same grievances, objectives, and targets as the law school originalists. But they were not as fixated on the promise of either neutral, ‘apolitical’ judging, or deference to legislatures in the name of democracy. Movement conservative constitutionalists argued for substantively conservative principles and values, including in the understanding of rights. Many of them argued that American Founders had embodied those conservative principles and values, and that the Constitution had enshrined them. Their interest was in substantively right principles and substantively right answers.

If legislatures got the values right, in ways that were authorized by the Constitution, judges should defer to the legislatures. If legislatures got the values wrong, in ways that were not authorized by the Constitution, the judges should aggressively repeal them. If, given the nature of the laws that were being passed, that entailed an aggressive, activist judiciary, then so be it.

As you pointed out, until recently every major school of political thought in America accepted the authority of the Declaration of Independence as a ‘creedal document’ even if they had constant disagreements over its exact meanings, implications, and role. However, nowadays, progressive movements such as ‘The 1619 Project’ or the ‘Woke movement’ question the very authority of this founding document. What challenges does it pose to the conservative movement?

The 1619 Project and what has been called ‘Wokeism’ have been boons, and generated opportunities for the conservative movement. Many Americans outside the insular elite subcultures of high-end American academia and blue-state urban enclaves recoil at the relentlessly didactic evangelism, dogmatism, intolerance, and bureaucratic and managerial coerciveness of these privileged, and often comically un-self-aware, elites. ‘Woke’ excesses, often emerging from academia, but also from the worlds of art and culture, and prestige media like National Public Radio and The New York Times, have provided an endless stream of mockable actions and initiatives that have played a major role in fuelling the rise of conservative media, and helping to recruit the next generation of conservative Republicans.

Progressives are hardly alone in promulgating dubious history and teaching it to students. But they have decided to plant their flag on a fundamental attack on the country’s history and heritage as source, ultimately, of meaningful membership and civic pride. In return, they offer little but endless debunking, and the thin gruel of a solipsistic identity politics, spiced with an off-putting self-righteousness and self-regard.

‘Most Americans remain patriotic and proud of their Founding, whatever its flaws. They recognize the necessity for change, reform, and progress’

The proponents of this idea have seriously miscalculated how these initiatives come off, even amongst members of the groups for whom they, ironically, purport to speak. Most Americans recognize that their country has problems, many deep and longstanding. But most Americans remain patriotic and proud of their Founding, whatever its flaws. They recognize the necessity for change, reform, and progress. The Democrats would be in a much stronger position politically without these embarrassing excesses in their camp, since their actual policies often align much more neatly with most Americans’ preferences. What Americans do not trust about Democrats is their values. And they take Woke values to be the values of the Democratic Party. Democratic elected officials, who mostly are not involved in these unfortunate developments, have been tarred by them. Electorally, at least, this helps the Republicans.

We can also see the emergence of national conservatism as well as ‘common-good constitutionalism’. How does national conservatism shape the conservative movement conception of policymaking? In what sense does ‘common-good constitutionalism’ differ from ‘originalism’?

National conservatism represents a new convergence amongst a set of rising traditionalist conservatives in the US rallying to the defence of what they take to be embattled Western traditions and traditional American values. In their signature manifesto, national conservatives have declared themselves in favour of national sovereignty, ‘the Constitution of 1787’, free enterprise, restricted immigration (with a presumption of assimilation), rigorously enforced law and order, and government supported, promoted—and, indeed, privileged—Christian morality. On the grounds that ‘all men are created equal in the image of God’, national conservatives have declared themselves to be against public and private racial discrimination.

In the American context, national conservatism’s distinctiveness lies in its frank willingness to charge governments with privileging Christianity over other religions, and to leverage government power to enforce conservative Christian moral understandings on the grounds that they are indubitably correct. National conservatives set themselves apart from some other conservatives by their criticisms of the power of trans-national corporations, and of the ravages of ungoverned capitalism. Their emphasis on national sovereignty and criticism of a globally oriented interventionist American foreign policy represents a retreat from the longstanding conservative Cold War anti-communist agenda, which was committed to the worldwide promotion of American-style (neo)liberalism and corporate capitalism.

How do you see the ‘common good constitutionalism’ theory put forward by Adrian Vermeule?

The attention being lavished on Vermeule’s ‘common-good constitutionalism’ is an artefact of the separation in the US of constitutional scholarship in the law schools from constitutional scholarship in other areas of intellectual and political life that I mentioned earlier. The primary objective of law school/legal academic constitutional theory has been to have those theories adopted by judges. The traditional test of a good law school constitutional theory is whether the theory has effectively removed all the substance in the name of a-political, procedural neutrality, so that the judge who adheres to it can plausibly claim to be deciding the case, not on the basis of prejudice, ideology, personal opinion, or politics, but by an objective application of ‘law’.

Conservative originalism is very much a part of this proceduralist project. Vermeule has seized attention by rejecting both constitutional theory’s limiting focus on judicial role as well as its proceduralist premises. This separates him not only from most progressives, but also, more provocatively, from his fellow conservatives, the originalists. Vermeule is far from unique in rejecting the ever-elusive quest for judicial neutrality in the name of law. On the liberal/ left, Ronald Dworkin advanced a (judge-focused) substantive moral vision, as have all manner of Marxian ‘Crits’—including radical feminists and critical race theorists—who have long rejected the ideal of legal-liberal neutrality.

Sidestepping the game, and the deeply-rooted legal academic constitutional theory agenda, Vermeule instead leads with an unapologetically substantive, and frankly pre-modern, traditionalist conservative programme and agenda, which he has characterized as involving a thoroughgoing commitment to ‘the common good’. Although he often hides the ball, Vermeule’s substantive understanding of what constitutes the common good is rooted in pre-modern traditionalist Roman Catholicism. For good measure, Vermeule claims that his substantive vision is more consistent with the understandings of the American founders than the proceduralist understandings of the conservative originalists, whose origins, as we have seen, was in the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century debates about democracy and Lochner-era judicial activism.

While Vermeule’s Common Good Constitutionalism (2022) goes more deeply into traditionalist legal thought, including Roman, Canon, and traditional international law, to recover his substantive foundations and ends, it is worth noting that—if one surveys the writings of post-war conservatives outside of legal academia—there is nothing new about frankly substantive conservative constitutional argument. Outside the law schools, movement scholars, activists, and theologians, including Christian evangelicals, fundamentalists, Pentecostalist charismatics, and radically traditionalist Roman Catholics (like Vermeule), and other traditionalist conservatives, including Straussians, have a long history of advancing substantive, as opposed to process-based, conservative constitutional theories and arguments. What is notable about ‘common-good constitutionalism’ is that it injects these morally substantive, ends-based constitutional arguments into a rather parochial elite of the legal academic world (in the US, law schools are separate professional schools that are detached from both the undergraduate teaching and PhD granting schools and departments of American universities) that either does not know about them or has not paid them any attention.

This leap of openly substantive conservative argument into a potentially agenda-setting role in the law-professorial world is nevertheless consequential: this is precisely how ideas and ideologies in the US make their way into the actual doctrines of American constitutional law. Notable too is that with the ascendancy of both national conservatism and common-good constitutionalism, there is a clear movement on the American right away from a concern with checking government power to a preoccupation with wielding it.

Related articles: