The following is a translation of an interview written by Anna Bakai, originally published in Magyar Krónika.

The oeuvre exhibition of one of the most original Hungarian artists of the turn of the century and early modernism can be visited at the Hungarian National Gallery until 27 August this year. To have a more precise understanding of Gulácsy, Magyar Krónika spoke with the exhibition’s curator, Gábor Bellák.

***

Many people consider the famous Hungarian painter, Lajos Gulácsy to be one of the most mysterious figures in Hungarian art history. What does he owe this attribute to?

Lajos Gulácsy had a very peculiar personality, with an art that is difficult to classify, moreover, if we look at his works in a purely technical sense, there are many clumsiness and flaws appearing in them. However, these irregularities somehow do not matter at all, since people are not enchanted by perfection, but rather by genuineness and authenticity. Gulácsy’s works are completely free of mannerisms: there are neither idles nor routines in them, but passion and feelings permeate all of his paintings.

Do the abovementioned imperfections stem from being a self-taught painter?

Yes, for though he studied at the Model School of Drawing in Budapest under Hungarian history and portrait painter Bertalan Székely, he couldn’t be graded as he didn’t really attend classes. After that, he continued his artistic studies in various free schools in Venice and Florence, but overall he can really be seen as a self-taught painter.

Gulácsy’s art cannot be attributed to any isms: he followed his own path. How could you describe this path?

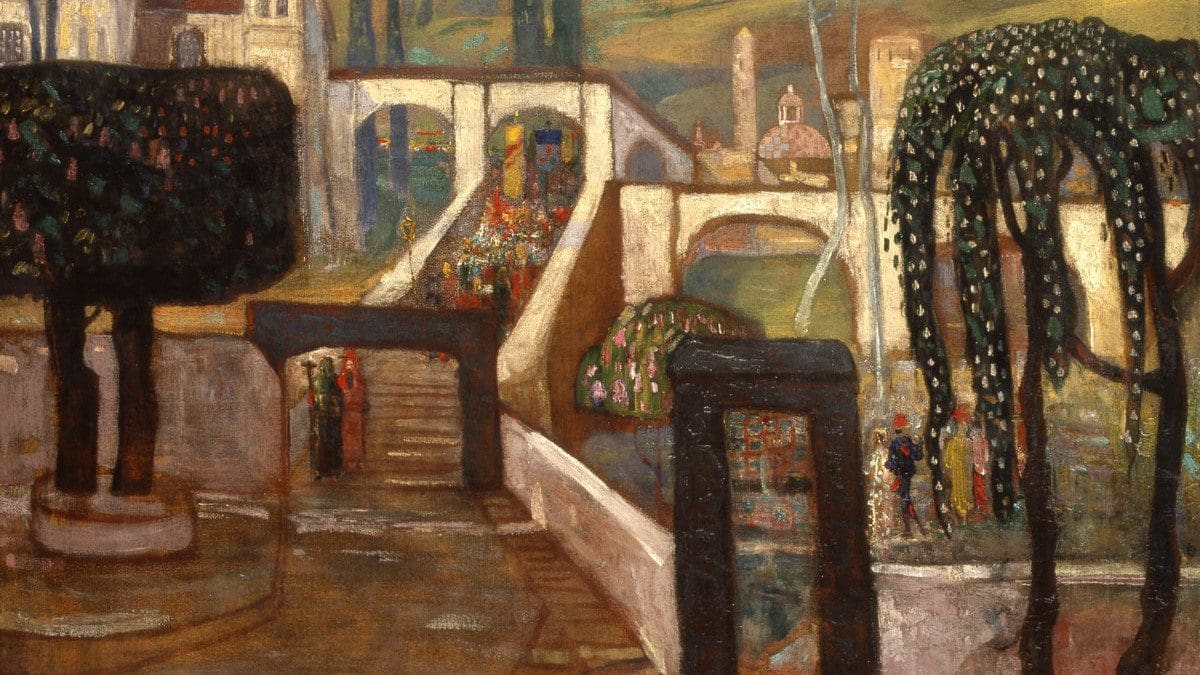

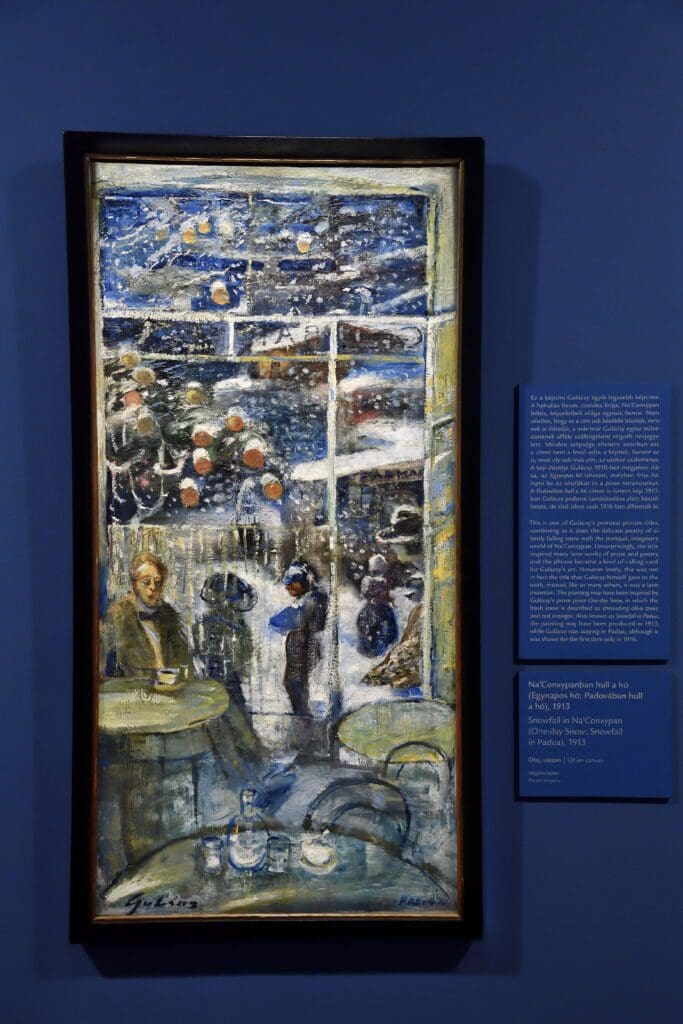

Gulácsy really cannot be included in any of the major trends of the early 20th century, but he may not even need to be. When studying the nature of his art, it is worth looking at what it was that fascinated him and what he wanted to express. The painter wrote about himself that he observed reality with one eye and dreams with the other. This duality can also be seen in his works: the strong imaginative content and the world of the surreal are clearly visible, for example, in his Na’Conxypan drawings, a world of dreams ruled by odd laws created by the painter himself. On the other hand, he was really passionate about reality—he made incredibly beautiful drawings of people, café girls, workers, or nature. He liked playing with different styles: he had rococo and renaissance pictures, but he also often painted in the Biedermeier style. He considered himself the heir of the entire history of art, i.e. the historia del arte, so he always created in the style he felt like. His had a unique, special path.

Apparently, he felt a strong attraction toward the past—but what was his attitude like towards the era in which he lived?

I think he must have felt like a stranger in his own era. He painted many self-portraits, in which he depicted himself in different roles, costumes, and sometimes even disguised as specific historical figures. He even loved to dress in different costumes in everyday life: in Florence and Budapest, he often wore strange historical clothes—sometimes he dressed as, for example, a medieval knight.

It seems that the feeling of longing was a strong sentiment he had.

Lajos Gulácsy was a person with immensely sensitive nerves. First, this weak nervous system collapsed in 1914, and then, despite short-term recoveries, he had a complete mental breakdown in the early 1920s. He spent the last eight years of his life in a mental institution. Although the aforementioned sensitivity arose from several sources, his extremely strong longing undoubtedly played a decisive role in it. In fact, the painter would have felt much more in place as a contemporary of Dante than as a member of the ‘electrical’ 20th century. Instead of letting his mind stray into the past with healthy sobriety, Gulácsy built an alternative world around himself, practically a shell in which it would have been impossible to survive in the long term without a split in his personality.

This duality is quite interesting since the aforementioned shell included the point of view of an active and open-minded person as well who, in addition to painting, also dealt with issues of art theory, designed sets, illustrated books, and wrote plays. Despite all his longings for the past, Gulácsy still had strong bonds with his contemporaries.

He longed for the past, yet in his criticisms he wrote surprisingly clearly and insightfully about his contemporaries. In his poems and Na’Conxypan stories, for instance, there is a lot of humour, too. Besides, among the big writers of the era, he had excellent friends and insightful analysts: for example, he was good friends with Hungarian poets Gyula Juhász and Ákos Dutka, but he also knew our great turn-of-the-century poet Endre Ady personally. Hungarian writers Dezső Kosztolányi and Milán Füst wrote sensitive criticisms about him, and in 1922, Gyula Juhász wrote perhaps one of the most beautiful poems an artist could ever write to another artist fellow. These all prove that Gulácsy was a recognised artist who, as long as he was able to create, created great and special artworks.

How was he perceived by the general public of the era?

This can only be measured by how successful his works were with collectors. He had constant financial problems, but he always had one or two major collectors. Thanks to them, many of his masterpieces could survive, but in the course of time, unfortunately, several of them have been lost, are missing, or were destroyed, such as one of the largest Gulácsy collections, which was destroyed in a fire in Báthory Street during the siege of Budapest.

How large is the Gulácsy oeuvre we know today?

A few years ago, I started collecting his artworks based on available sources, exhibition catalogues, and various other collections, so at this point, together with all his paintings and graphics, we can talk about a thousand items, about half of which can be properly identified. It is therefore a significant event that the public can now inspect nearly two hundred of these five hundred masterpieces at the exhibition in the Hungarian National Gallery.

Is there a particular reason the exhibition has been organised now?

The exhibition was originally planned for 2022, as we could have linked it to several anniversaries last year: 1922 was the year of the last exhibition organised during Gulácsy’s lifetime; he was born in 1882; and he died in 1932. However, it is much more important than the anniversaries that there has never been a Gulácsy exhibition on the premises of the largest collector of Hungarian art, the Hungarian National Gallery, even though he is one of the best-known and most loved Hungarian painters. The organisation of such an exhibition requires long preparation, one of the most difficult parts of which is to come up with a concept with which we can say something new and different from what has been said about Gulácsy so far.

What was the ‘something different’ thing in this case?

We tried to make the one-sided image of Gulácsy in Hungarian art history more nuanced. When talking about him, we tend to imagine a strange, dreamy, foolish figure, in whom we want to see a wizard of lyricism, sensitivity, and poetry. I, on the other hand, think that Gulácsy was not only a painter of dreams but an artist who obstinately observed reality, too. Posterity strongly reinterpreted his works based on this arbitrarily constructed image—we now wanted to free his oeuvre of these superimposed layers. To this end, we also present images that have never been exhibited before. It is also interesting to note that the gallery’s collection includes several of his pictures that have never been seen by the public and were not even asked to be borrowed for other exhibitions either.

Do they not fit the public image of Gulácsy?

Maybe that could be the reason. They were not considered interesting or important enough—we, however, strove not to recreate the painter according to our own expectations, but to show the real Lajos Gulácsy who actually emerges from his artworks.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.