In Hungary, 16 April is the Day of Remembrance for the Hungarian Victims of the Holocaust, marking the beginning of the ghettoization of Hungarian Jews in 1944. If we want to learn about these horrific events of World War II through personal stories, we are at the eleventh hour. I can call myself lucky because I had the honour to talk to a person who survived one of the darkest periods in history, and who clearly remembers the events.

Hungarian Holocaust survivor Mrs Éva Reitlinger Geiger was born on 16 January 1937 in Buda, in the 2nd district. She was only seven years old when her family’s ordeal began. I sat down with Aunt Éva to listen to her crystal-clear memories of what happened to her family between 1944 to 1945.

***

Where did you and your family live in the early 1940s? Can you tell us a little bit about your family?

My father, László Reitlinger, was baptised in the early 1930s and became a Calvinist. He attended a German university and studied textile engineering. In 1935, he married my mother, Edit Kohn, who only wanted to convert and leave the Israelite religion in 1944, hoping it might help her situation, but then it was already too late. We, the children, were baptised as Calvinists, but we were not observant. From my birth, we lived in Tövis Street in the 2nd district. Apart from us, there were no other Jews in the area, so I don’t have such terrible memories as, say, my later husband, Tibor Geiger, who lived at 47 Király Street in the 6th district.

Were you an only child?

No, my sister was born in 1943. To this day, I regularly ask myself the question: how did my parents dare to have another child during these hellish years? It is true though that they did not even know about the death camps, nor about the situation of rural Jews. Perhaps there is no other explanation. My father was called up for labour service several times, but in the end, he was never taken because of his sick leg. Thus, the beginning of the 1940s did not cause much drama for our close family. My father worked as a scribe in the small town of Nagykáta. Since he could not be taken to forced labour due to his health, he worked in the Adria Silk Weaving Factory, practically, as a factory manager, where they manufactured parachutes. He could continue working until the German occupation of Hungary on 19 March 1944.

How did you experience the air raids as a child?

The air raids were awful; it was terrible to hear the sound of the sirens. It always made me throw a tantrum. During one of the attacks, [acclaimed Hungarian writer and publicist] Lajos Zilahy’s villa in Áfonya Street was hit as well—I remember that my father and I looked at it the next day. I still have before me the bathtub hanging upside down, peeking out of the ruins.

How was your life different after the German occupation?

I vividly remember 19 March 1944. It was sleeting. The area was not as densely built as it is today; there was a huge meadow next to our house, which hummed strangely at the dawn of that day. When it really started to get light, we were faced with the fact that there were dozens of German tanks and military vehicles in our immediate vicinity. We had guests at the time: a friend of my mother with her husband and their daughter, Nóri, who had fled to us from Zagreb. They were also Jews. When the little girl saw the German tanks, she fainted. The reason that had made them flee their home now caught up with them here in Budapest. The German presence also meant that our radios, cars, and jewellery had to be turned in. That was the first time I saw my father cry because he had to part with his beloved Fiat Balilla. It was also very painful for him since he considered himself a ‘true Hungarian’, and he never thought he would end up in a situation like that.

How did you get along with the Germans ‘next door’?

The German officers regularly visited us for tea. We all spoke German, so we had quite pleasant chats with them. The decree for the establishment of yellow-star houses meant that the situation suddenly worsened: no matter who had converted to which religion, soon we all had to wear the same distinguishing star. Our house was also marked with a yellow star, but only for two days, because after that we had to leave within 24 hours. We could only bring a stroller full of our belongings with us; everything else was left behind.

Where did they take you after that?

They took Nóri’s family and my grandfather, Dezső Reitlinger, to the brick factory in Óbuda, and my grandmother somewhere else. Nóri’s family was later sent to Auschwitz—the only survivor was the little girl. It was from her that I learned much later that Arrow Cross men shot my grandfather dead in the brick factory because he ‘worked too slowly’. My sister, my mother, my father, and I went to 54 Pozsonyi Street, where the relatives of my sister’s godparents lived. They were Christians. They accommodated us in the hall. Later, the house was placed under Swiss protection.

At that time, there was already a curfew, and our life became even more difficult. My mother had a friend, Mrs Erzsébet Dénes, who was a Christian, but whose husband was a Jew and died during forced labour service. She always brought us milk so that we could feed my little sister. It was thanks to her that we didn’t starve to death—she always took the risk of delivering food to us. Meanwhile, we had absolutely no idea what was going on in the countryside.

It couldn’t have been easy to live in such a small apartment…

Certainly not. But in August 1944, our situation changed. Until then, a Romanian actress from Bucharest had lived in the building, but she left Hungary and returned home after the transition in Romania, so we could move into her place. In the meantime, my mother looked up where my grandmother was and brought her to us. We lived in this sheltered house until the coup orchestrated by Ferenc Szálasi, the leader of the Arrow Cross Party–Hungarist Movement, in October. I received a lot of slaps from my parents in those months for going out of the house to play and often coming home late.

Then came Szálasi’s coup…

Yes. I will never forget the day of 15 October. Wherever there was a radio in the street, everyone listened to Governor Miklós Horthy’s announcement that we were withdrawing from the war. People who did not even know each other embraced, Jews and non-Jews alike. The next day, we were faced with the fact that Horthy’s plan had failed, and Arrow-Cross raids began. They went from flat to flat. From then on, I couldn’t even go outside to play—our situation became increasingly uncertain. At the beginning of November, during a raid like this, we were told that we had to leave 54 Pozsonyi Road. We had to wear a yellow star and could not take any luggage with us. We were redirected to 38 Tátra Street—hundreds of us gathered there. On that same day, those over the age of 40 were transferred elsewhere. In the first round, all men were driven out and then came the women as well. A Hungarian gendarme took pity on us and hid us behind the tile stove in one of the apartments of the house, but an Arrow Cross man found us and forced us to go down, too. He tore my sister out of my mother’s hands and threw the baby away; I managed to catch her, otherwise, who knows what would have happened to her. In the end, they left us children behind and only took the adults away.

How did you get along on your own as little children?

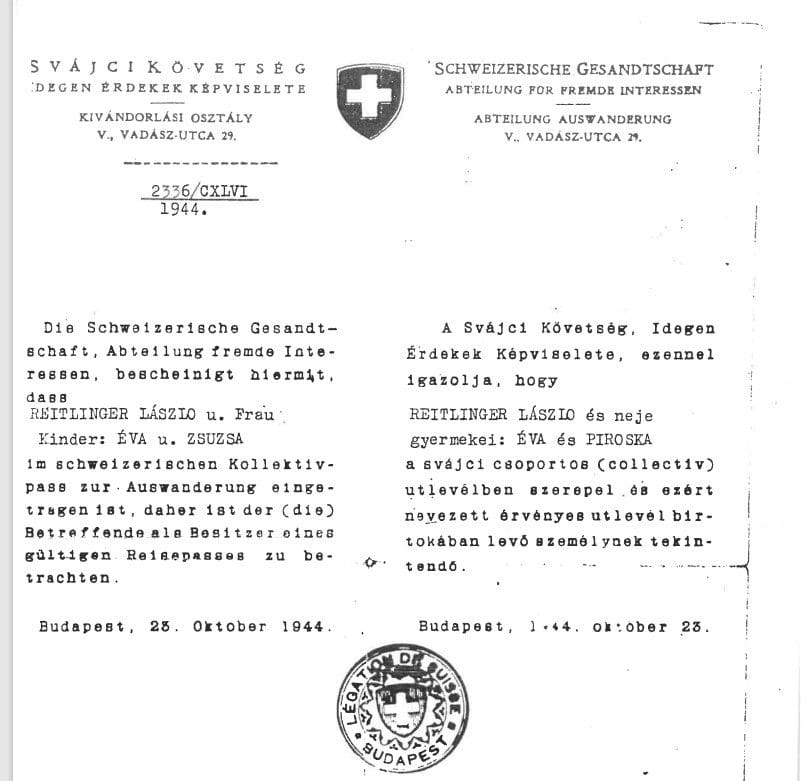

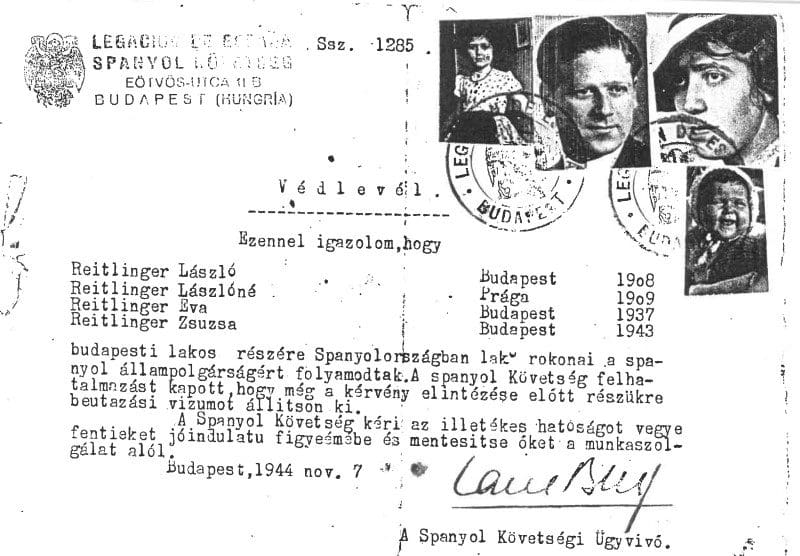

We wandered around this apartment for two or three days, looking for food. We didn’t dare to leave the building. I found some biscuits—I fed them to my little sister. After being taken, my grandmother tore off her yellow star and ran away. She came back for us soon and we tried to go back to the Pozsonyi Road apartment, where they did not want to let us in, because other Jews had already arrived in our place. When we pointed to our belongings, we were finally allowed inside. We didn’t know anything about my parents, and Mrs Dénes was no longer able to help us either. I was a lot of trouble to my grandmother; I regularly went out to the balcony, despite her prohibition, to look about from there. On one such occasion, I got pneumonia. As it turned out, my parents were on their way to the western border in the death march from Gönyű in early November 1944. At that time, they could no longer be taken to Auschwitz. If my mother hadn’t been there, my father would have certainly been shot dead as he could hardly walk because of his gammy leg. At Hegyeshalom, they received a protective letter from the Spanish Embassy on 7 November—as it turned out, it was the people of Giorgio Perlasca [an Italian businessman who posed as the Spanish Consul General to Hungary and saved thousands of Jews from deportation] who helped them.

I guess they immediately tried to come back to the capital.

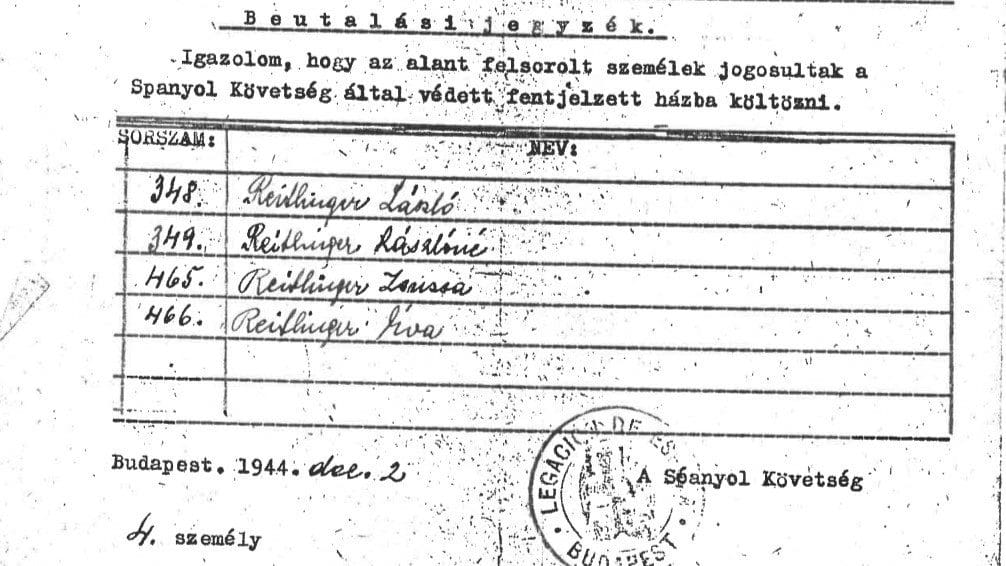

Exactly, although at the time the Russians began to surround Budapest, so it was not easy to return. My mother looked for us at 38 Tátra Street at once, exactly where we had parted earlier. There she was frightened to death to hear that we had been deported—she didn’t want to believe her ears, so she immediately looked for us in the flat on Pozsonyi Road. My parents arrived there as human wreckages, having dysentery and lice. They were only able to enter the building with great difficulty—there were already so many of us in there that we didn’t even fit into the basement when the air-raid alarm sounded. Therefore, on 2 December, my mother managed to get the Spanish Embassy move the four of us into a protected house in Főnix Street (today’s Raoul Wallenberg Street).

At Christmas, Mrs Dénes showed up with a small pine tree and candles—even though we were Jewish, she knew that we always celebrated Christmas and Easter.

At that point, did you already see some light at the end of the tunnel? Did you feel more peaceful that perhaps the worst part is finally over?

I would not say that. The house opposite was hit by a bomb, and the flying splinters almost killed my sister and me. There was a lot of snow that winter, and we lived in the basement until 20 January. My mother washed us in the snow, but we still had lice. Through the gaps in the door, I saw Arrow Cross soldiers leading people to the Danube bank to be shot to death. I also witnessed that those who could no longer walk were shot dead then and there, on the street. Then, on 16 January, suddenly great silence prevailed in the area. We were alarmed by this; we were so used to the constant noise. We couldn’t imagine what could have happened. Soon, a Mongolian-faced soldier with a machine gun opened the door, searching for Germans. After that, a Soviet officer also arrived, and tried to find out if any of us spoke German. My father spoke to him. He urged us to stay inside, and he later returned again. He brought me a tiny silver pistol as a present because he learned that it was my birthday. That was when we first started to believe that we wouldn’t be shot into the Danube. We returned to Pozsonyi Street at the end of January: the building didn’t get hit by a bomb, so we could move back to two rooms in the hall. A few weeks later, our relatives began to return, too. I remember watching the Soviet occupation of Margaret Island together with my father.

When could you return to your real home in Buda?

In April 1945, my father was brought over the Manci Bridge (a temporary pontoon bridge built next to Margaret Bridge) to Buda to see what happened to our house, to our home. There were sixteen bodies in our garden, German and Soviet soldiers, but there was also a dead horse. The house was shot up. For months, we lived with a carpet hanging over the door, and the roof of the building was covered with tar. Because of these memories, it happened a lot that I screamed all night long in my dream.

Many thanks to you Aunt Éva for sharing all these experiences with us. I wish you good health!

You are very welcome. As long as I live, it is my duty to tell our story.

Related articles: