This interview was first published in Hungarian on 777.hu.

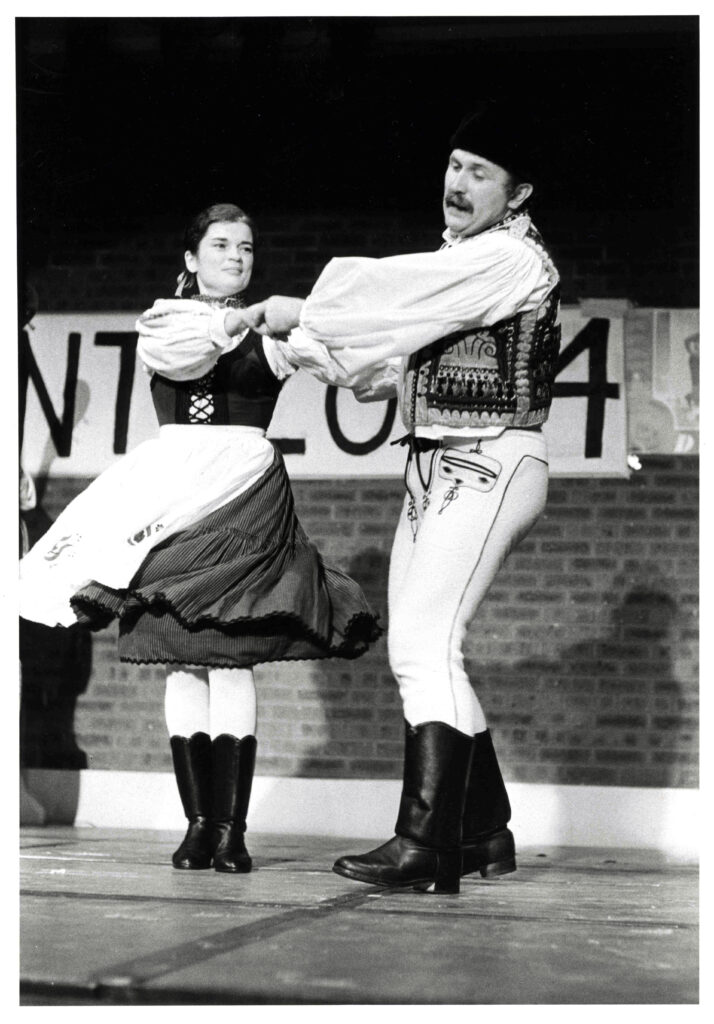

I first met Kálmán Magyar at the Pontozó Hungarian folk-dance festival, the biggest of its kind in North America held this year [2023] in New Brunswick, New Jersey, where he was the president of the jury. I was also interested in his adventurous private life—he immigrated to America with his father at the age of 18, after his mother left with his twin sisters six years earlier—but he insisted that we should focus on the Hungarian American folk dance movement, in the revival and renewal of which he and his wife played a decisive role in the ’60s and ’70s, and which he himself didn’t think would still flourish in the diaspora fifty years later.

***

How do you evaluate this year’s competition, compared to the beginnings?

The experience is still fresh now, but I’m trying to collect my thoughts. To compare, I have to tell you how it started. After the great waves of immigration following World War II and the Hungarian revolution and freedom fight in ’56, Hungarian folk-dance groups began forming also in New York. In the meantime, negative competition started, too: everyone collected the materials from somewhere and kept it for themselves, said bad things about the others, etc. I fell into this environment in the ’60s, when I became the artistic director of the Hungária dance group in New York, and I didn’t understand it. I thought that our common goal was to share our Hungarian folk culture and preserve it as a public treasure. That’s why in ’74 we brought together all the dance groups from New York in the Hungarian American Athletic Club (HAAC) in New Brunswick, which was a very big thing at the time: they performed on the same stage and had a positive attitude towards each other. By the way, the young people had no problems with each other, but the leaders… In addition, a few years later, there was a Hungarian festival in the huge outdoor stage in Holmdel, New Jersey with a capacity of 10,000, organized by Rev. Imre Bertalan, in agreement with the leaders of the state of New Jersey. I turned to him and suggested that we bring something special there, for example, a folk-dance festival. That was the first Pontozó. We disqualified three large, established groups, because we wanted to give an opportunity to the smaller ones, so finally seven or eight dance groups competed and an American group—with only American members—won.

In the meantime, my wife—who I know due to folk dancing, since I met her in the Hungária folk dance ensemble—started a publication, called Karikázó. This was a quarterly magazine in the pre-Internet age, where we reported on dance events and shared reviews. The magazine developed along with Pontozó. Since Judit and I were already teaching at folk dance camps, we had an increasingly large circle of acquaintances, and it became our goal to get together with the dance groups outside the New York region.

As a next step, we organized the first Hungarian Folkdance Symposium, which was also an important event, because it provided an opportunity for further education: we brought the best dance teachers from Hungary and provided live music. Later, I asked my friend Kálmán Dreisziger, who led the Kodály ensemble in Toronto, to take over Pontozó, and we agreed that there would be a district competition every year, and a main competition every other year, for the previous year’s winners. We built it on the Hungarian model, like many things in folk dance. The Symposium was a new idea, because there were different ethnic folk-dance camps, mainly on Balkan folk music and dance, which is why we also organized a Hungarian camp.

What were the sources of Hungarian folk life at that time here?

At that time, we had nothing—no information, no materials, no live music, no professionals—so we progressed very slowly. What we saw here at Pontozó today is very similar to amateur competitions in Hungary—both in terms of music and dance, since nowadays we have more and more events with live music. Two bands performed today, and my grandson Lacika Hajdú-Németh, who lives in Hungary, also played. In the ‘60s and ’70s, there were dance ensembles that performed ballets to the music of Brahms, and they thought it was Hungarian folk dance. This was understandable, but it was only an imagined romance, it had very little to do with the original Hungarian folk music and folk dance. At that time, the dance hall (táncház in Hungarian) movement started in Hungary and our goal was to persuade Hungarian Americans to follow suit. So we grew simultaneously with the folk dance movement back home, the merits of which I don’t need to describe, but if it had to be summed up in one sentence, it would be: the transfer of traditional village culture to the city populations.

By the way, there are new attempts to focus not only on dance, but also to save the village lifestyle—animal husbandry, clothing, religious life, and communities. For example, in Kiscsősz, the life of the entire village is about the preservation of traditions. The Cleveland Scouts folk dancers are also trying to connect with this movement: they regularly visit Palócföld and live with the locals. The reason the girls were able to present the karikázó dance so beautifully, because they experienced it in its original environment.Another very important element is the connection between generations, the example setting. My children and grandchildren play music and dance. Lacika has just been invited here as a first violin player (prímás in Hungarian) and he has played music with his old friends and performed with his other grandfather, who leads the church choir and led a special choreography on the stage called Férfierő (‘Male Power’). But the Kosbor or the Tóth families were also on stage together—and that’s why I liked the Schachinger family’s performance, where the parents and their children were dancing together. If you involve your children, i.e. you don’t just take them to dance lessons and deal with your business, but you participate in it together with them, then this culture will become much more ingrained in your children and will probably remain important for their whole lives.

Does Pontozó reach the level of Hungarian amateur competitions also in terms of quality?

The quality is not always of the highest level, but I don’t want to criticize anyone right now, it wasn’t the job of the jury either, we’ll sort that out at the professional discussion after the competition, but we won’t criticize them, for example, because in the Rábaközi dance they took on the costumes of eight different villages. Or, for example, two people came from New Hampshire, who keep Hungarian culture alive there—why should we tear their dance apart? I’d rather kiss them a hundred times. They are going to dance at the celebration on March 15 in Boston, because there is no dance group there (yet). If I criticize them strongly, they lose their enthusiasm. Everyone received recognition because they deserved it for participating and for nurturing Hungarian folk culture once or twice a week.

This is the level where we can safely say: every step, every dance was good—because they are much further ahead than we were when we started. I remember when the Hungarian State Folk Ensemble toured here, and I complained to their director about how difficult it was for us here, because we had neither material nor live music, Miklós Rábai replied: ‘Kálmán, just do it anyway, because the most important is that you do it!’ I took that as a guideline and didn’t mind if we got one step wrong. Today we should know the right steps, because we have access to teachers, materials and even live music also in the diaspora.

What about quantity? We saw twenty or so young people of the same age in the Cleveland Regös group, but no one else, not even the New Brunswick teams, had those numbers.

The quantity is another matter, it’s not just about folk culture. It’s clear that the Hungarian communities are constantly shrinking and weakening, but that’s natural. It shouldn’t be viewed with sadness, because thank God we don’t have a national tragedy and therefore no mass immigration from Hungary has taken place lately, unlike before, subsequently to the World Wars and the revolution of ’56, or very recently, for example, from Transcarpathia. The Ukrainian community in Pennsylvania, around Pittsburgh, is getting stronger now. We don’t and shouldn’t have that. There were huge Hungarian enclaves for instance in Pittsburgh or Youngstown, Ohio, but they have assimilated into the American communities over the past few decades. There are no dance groups in Akron, Ohio anymore either, but there are still some in places like Cleveland, Ohio or New Brunswick, New Jersey or Chicago. But the number of Hungarians is decreasing here as well: women used to stand in line to cook in the HAAC; today there are hardly any who are willing to volunteer. I remember that every week at St. Stephen’s Church in New York, they made such donuts (fánk) that people came from all over the city to have some, but those generations passed away and the younger generations didn’t take these community traditions over. As I said, this is a natural and unstoppable process; especially since we are no longer isolated.

Would that also mean that it’s not worth doing anything about it?

That’s not what I meant. There is a village, Óbánya, near Pécs, Hungary. We went there recently, and the Bible was read in German at the Sunday mass, even though Germans migrated there over 500 years ago, but the few German-speaking parishioners who are still alive insist on it. This doesn’t work in America: the McDonald’s culture is too strong here and absorbs everyone’s ethnic identity—unless one consciously acts against it. I note that the Hungarian state has recognized this and is trying to help, for example with the Kőrösi Csoma Sándor Program (KCSP) scholarships. If we didn’t have such good KCSP scholars —community organizers sent by the Hungarian State to the Hungarian communities of the diaspora with a fixed-term scholarship, typically in their twenties—this festival would not have been organized to such high quality either.

Where there is help and there is a strong community activity, folk dance, scouting, Church and Hungarian school, there will be survival. Elsewhere, Hungarian communities will disappear. It’s natural and doesn’t bother me. This is because, as I said, there is no national trauma. In addition, those who are in the enclave are all ambassadors of Hungarian culture. Me, you, and everyone who lives here and does something for Hungarians. This needs to be strengthened, which is why, for example, dual citizenship or the ReConnect Hungary Program are also very useful. The point is that the absolute number of those claiming Hungarian descent in the American censuses, approx. 1.5 million, has remained largely unchanged over the past few decades. Even if the communities dwindle, there will always be those who will do their best to be ‘Hungarian’. Because what does it take for someone to remain Hungarian in the diaspora? You need a Hungarian identity—for me, this was strengthened in America, for example, through Hungarian scouting and Hungarian folk dance—and a culture you are proud of that you don’t throw away and don’t replace. However, as noted, you need a Hungarian community in which you want to participate, and with the help of which you can strengthen your Hungarian identity. Folk dance and folk music are one of the best tools for this; it can even cross language boundaries.

Do you refer to the fact you can’t hear the American accent when one sings? Or to the fact that a Japanese couple also participated in this competition? Or that the bass player of the local Hungarian Fészer Band is of Slovak origin?

For these as well, but not only. The Japanese couple are members of the Chicago team, but they live far from the city and sometimes fly two hours to Chicago for a rehearsal. The Japanese are very fond of Hungarian folk music anyway, Sándor Tímár was in Japan often, but they were also fanatically loved in Hong Kong. The Tisza group in Washington DC was once purely American, now there are also Hungarians in the group, and they are doing excellently, because their founding leaders, Cathy and Rudi, went to Nyíregyháza, Hungary, where they learned not only dance, but also the language. But these are exceptions; there are not many American groups dancing Hungarian folk dance anymore, because táncház has taken over this role. There will be many Americans in tonight’s táncház as well. For example, I just met Claire Bright, who also likes Hungarian music very much, and created—at my suggestion—the Fényes Banda (Bright Band).

You said several times that our culture is the most beautiful in the world…

Yes, because it has been proved: there is no coincidence that the Hungarian táncház method was added to UNESCO’s list of intellectual heritage, in the register of best conservation practices. This is very special: we learn our own culture on an organized basis, thanks to Halmos, Sebő and Tímár. Hungarian dance has charm, the dance of Kalotaszeg and Mezőség is wonderful. It’s like rock n’ roll for African Americans. You have seen the little ones dance and sing, haven’t you? It’s all about the relationship, about life…

…but what does a foreigner see in it?

The Japanese are not interested in the text, but in the dance, which is new to them, because men can hold the women’s hands, for example. Did you see the dancing woman’s face today, how stiff it was? Only the man could let himself go. In America, there was an international folk-dance movement that flourished from the ’50s to the ’80s, it was called ‘international folk dancing’. Participants got together regularly and learned to dance folk dances of various nations, mainly Bulgarian, Romanian, Serbian, mostly dances that do not require having a partner. My wife and I also got into this movement. Judit and I were often invited to folk dance camps, where we taught them Hungarian dances for one or two weeks. We taught short choreographies; they really liked the special music and the steps—in those few minutes they felt like Hungarians. As a dance teacher or organizer, nothing else gives me a better feeling than seeing people who like and respect my culture—because those acknowledge me as well. The most important thing for every human being is to be recognized and respected, I think.

In an interview, you stated that family comes first, even before Hungarian identity or folk dance.

I saw many positive and negative examples, from which I learned a lot. The former were, for example, Tibor Cseh, Gábor Bodnár, András Hamza—I followed them. We invested a lot of time into folk-dance, financially too—if we hadn’t done it, I would have a much bigger house today, but there was no question about doing it. I might have organized a tour until 2 a.m. in the morning, but I had to be at work at 8 a.m. The most important thing was to support my family. It’s not enough to nurture your Hungarian identity, you have to do everything to maintain a happy family life. That’s why I considered myself having a double identity and didn’t mix the two: I was American at work; they knew that I was from Hungary, but I didn’t discuss my involvement in Hungarian cultural life. It wouldn’t have been a smart thing to mix it up, because the Americans would not have understood why I was organizing Hungarian folk events and tours, instead of going to a baseball or football game? I’ve always led a double life, and I think most of us are like that. Nowadays I can put the two together since I’m the boss of my own company, but as a subordinate it wouldn’t have worked out well.

‘There was no question about doing it’, you said. Why?

Because this is the greatest experience for us. I’ll give you another example. When we toured with the 1848 program of the Hungarian National Dance Ensemble, it touched the audience so much that during the last dance everyone jumped up and started clapping—the show always ended with a standing ovation. I saw that the audience—Hungarians and non-Hungarians—were very enthusiastic, completely captivated by the dynamic Hungarian folk dance and music. Or look at this festival… Fifty years ago I would not think it would turn out like this. Back then, we didn’t think so far ahead, we just simply loved it and wanted to do it. Our folk culture had to be researched, it was a mystery to be learned, and we just had to do it.

In other words, you still ‘do it’ today, in Hungary and at the age of 78…

As I always say, we’ve been re-immigrants (visszidensek in Hungarian) for the past 13 years and we feel very much at home in Hungary. And as long as I’m able to do so—both in my company and in the field of folk dance—I’ll definitely work and support Hungarian folk culture.

Read more Diaspora articles: