It is not easy to be an ethnic Hungarian living in Transylvania, even 30 years after the regime change. This especially holds true for athletes. Recently, Roland Niczuly, the goalkeeper for the Sepsi OSK football team was asked how it feels to hear thousands chanting ‘Out with the Hungarians from the country!’ at Romanian league games. He briefly answered: ‘It doesn’t feel like anything. I’m so used to it by now that I don’t even hear it, really.’

Well then, what must have been like to be a Hungarian football player in the 1970s and 1980s, at a time when the Ceaușescu regime was in full force, a regime which, despite its appearance, was not only Communist, but chauvinistic too, and did everything to do away with the Hungarian minority? I discussed this with István András Kiss, hailing from Magyarbirkal, Kalotaszeg (Bicălatu, Țara Călatei), who used to play for the Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca)-based CFR in the above-mentioned decades, in a team originally founded as Kolozsvári Vasutas (Kolozsvár Railwaymen) in the pre-Trianon era, 1907.

How did you come in contact with football? Was it love at first sight?

I was born on 19 December 1967 in Kolozsvár. We were a working-class family, with no athletes. I first went to a football game in the spring of 1977, my brother Jóska took me. That’s when I fell in love with football, and we have been inseparable since. I remember that the game in question was Kolozsvár vs. Nagybánya (Baia Mare), and Kolozsvár won 5–2. I was amazed by the field. There was no running track around it, which was rare at the time. This ‘English-style’ pitch amazed me.

First, only as an outside spectator… How did you become an active player?

I started playing football in the summer of 1976, for the Kolozsvár U (Universitatea, meaning University). I had been coming to practice for about two weeks there, but when I saw that the slag pitch at the Sétatér (today, it is called Parcul Central) Stadium, the place where the new stadium (Stadionul Municipial Cluj Napoca, known as Cluj Arena or Kolozsvár Arena today) 40–50 children were doing football practice, I decided to go up to Fellegvár (cartierul Gruia), hoping that the training sessions there would have fewer kids.

There still were about 30 boys there, but at least not 50. I started going to Gépész Street (strada Romulus Vuia) in April 1977. It is important to note that one of my classmates, Sándor Fóla, played a big role in my changing teams—we switched clubs together. CFR (‘the Railwaymen’) were not as attractive to play for as U back then. 70 per cent of children wanted to play for the university team.

Was the change worth it?

I think so. While at U, I was coached by Coach Bandi Sepsi, who played for the Romanian National Team at the 1933 Balkan Cup and was the coach for the 1965 Romanian Cup-winning university team, but I got to work under exceptionally great trainers at CFR as well. Coach Pista Nagy was the head coach, an iconic figure in the club’s history, he raised the team who went on to win the youth league as well.

He was the type of coach who made children love football.

Training at this level only consisted of gameplay. We did not even need anything more, as this way, it immediately showed who is skilled in the game and who is reliable as a person. This is already apparent from how frequently one attends training.

Coach Nagy praised me a lot, and never told me off. He was an excellent teacher, even though he had no formal training in education. No one was officially signed by the club at that point. First they wanted to make sure if it was worth officially tying someone to the club.

When did that time come for you?

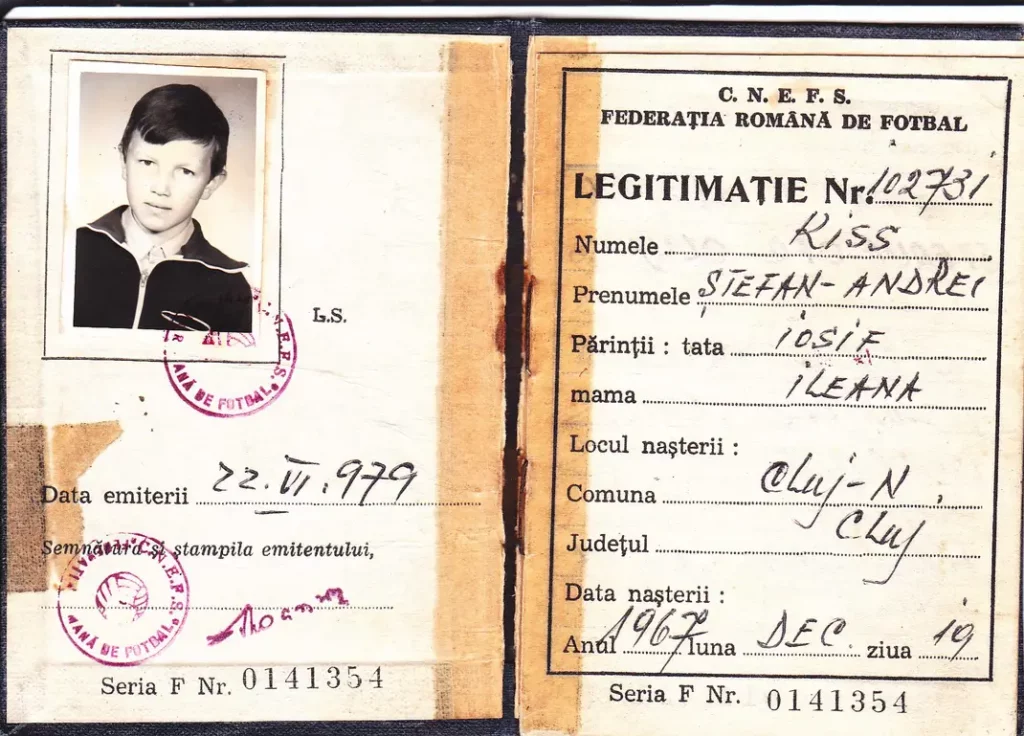

I became a formally registered player for the team in 1979. We first competed in the city championship. I’ll never forget it: we did not have strong enough legs to take the corners from the usual spot, so we took them from where the byline and the penalty box line meet.

There was no age limit within the ‘kids’ championship’. That’s why I got to play against Zsolt Muzsnay, two years my senior, who ended up making six caps for the Romanian National Team, and playing for clubs such as Kolozsvár U, Bihar (FC Bihor), and Steaua Bucureşti. He is the player [legendary Hungarian football commentator] Tamás Vitrai called the most technically skilled in the Hungarian league in 1991, when Muzsnay was playing for Fehérvár.

So, you got to be an officially registered player for the club. How did you then get to be part of the first team’s roster?

I am not exaggerating when I tell you I had to climb up the ranks. In 1983, I was picked for the Kolozs (Cluj) County all-star team. Our team was made up of CFR and U players. We ended up placing fourth in the national competition. I have a photo from the game we played on 22 July 1983, we beat Bihar 3–1. Sabău Lenuțu, who ended up being capped 55 times for Romania, was in our squad.

I played my first game for the CFR first team on 27 October 1983, when I was 15 years and 10 months old at the time, and played in a domestic cup game against Láposbánya (Băițan), in Máramaros (Maramureș) County. I got about 20 minutes on the pitch. Then, we won the youth league with in the 1984–1985 season. Only players under the age of 18 got to be involved in that competition. The members of the league winning squad were: Attila Marton, Sándor Diményi, Cristian Mayer, Sorin Urian, Zoltán Nosztray, Cristian Moldovan, József Orosz, myself, Sándor Lengyel, Constantin Olariu, and Niculae Cucuruzan.

Nine players out of them got to play at least a third-division level as an adult, but some even got to the first or second division. The club operated under the purview of the Northern Transylvanian Railway Corporation, a company that employed over 30,000 people.

The head of sports affairs at the company, Zemiánszky,

asked youth team coach József Szóher how come his youth league winning team had six key players who were ethnic Hungarians.

The entire squad was made up of eight Romanians and eight Hungarians. He did not have much of an explanation. 11 of us in the squad were raised together, we were good friends, almost brothers even. They never called me ‘homeless’.

There was no Romanian–Hungarian conflict, even if some of the higher-ups may have wanted that.

What’s important is that I got to play four domestic cup games for the adult first team, who were in the second division at the time. Apart from me, only three or four other players from my age group got such an opportunity then.

A cup game is ‘just’ a cup game. When did you make your debut in the league?

I played my first adult league game on 24 March 1985, at age 17. I earned the chance based on my previous achievements. I was in the starting line-up and played through the whole games in the next seven league rounds. However, I got injured in round eight. The injury weakened me very much, I couldn’t train, and thus I found myself in the youth team again.

It was a big deal that I got to train with the 1984–1985 first team. They had five or six players who had played in the Romanian first division before, quite a lot of games. Such players were, for example, Aurel Mureşan, Zoltán Náger, Ţegan, Albu, Berindei, and Lăzăreanu. They also had quite a few people with second-division experience, such as Popa Horea, Sándor Tóth, or Mihai Pop. They were highly skilled footballers. Many of them stayed out on the pitch after training, with me and my youth teammate Jószef Orosz—who later played for Paks in the Hungarian second division from 1991—and they taught us a lot. It did have a price, however, we had to buy them a few beers.

People really liked football back then. We were playing in the second division, still, at a mid-week, Wednesday game against Temesvár (Timișoara) there were 20,000 fans in attendance at the Temesvár City Stadium. It was an unspeakable experience to play in front of that many people.

In a 2019 interview for kronikaonline.ro, former CFR player Zoltán Kilin called the eponym of the modern ‘railway stadium’ in Cluj, Constantin Rădulescu, who is also regarded as an iconic figure in Romania’s and Kolozsvár’s football history, a ‘chauvinist bastard’. Do you have any memories of him?

I know Dr Constantin Rădulescu, whom the current stadium is named after, personally. I don’t know how much of a chauvinist he was, but it is certain that

in Romanian Communism, class warfare and chauvinism could easily co-exist.

It is also certain that sports was under the direction of the Communist Party. Rădulescu was aware of my being moved from the youth to the first team, as ‘the Doc’ was playing friendly games on Wednesdays, where he split the squad into two sides. He was an otorhinolaryngologist by trade, I even saw him as a patient once, I had a sinus infection. When the Doc called me up for the first team, Mihai Adam was the assistant coach, who was the Romanian league’s top scorer three times, in 1965, 1968, and 1975.

Could you give an example of how the Communist Party had an influence on Kolozsvár’s football?

Of course. In my childhood, CFR mainly played in the second division, while U had a solid first-division team. However, there were times when both teams played in the top tier, for example, between 1969 and 1976. In the off-seasons, players were often traded back and forth between the teams. It was often the Romanian Communist Party who decided which player should play for which club. The political leadership of Kolozsvár at the time—Ştefan Mocuța was the party secretary—made these calls.

In 1976, when both teams got relegated from the A league, and CFR had a really strong squad (a few of the talented players were Zoltán Náger, Lupu, József Szőke, János Román, Ion Ciocan, Manu, Mihai Liviu, Tegean, Batacliu, Hurloi, and Coman), they had a hard-fought promotion race against Nagybánya (Baia Mare). CFR won 5–2 in Kolozsvár, but Nagybánya ended up being promoted at the end of the season with a one-point advantage, since U did not let CFR win in the Kolozsvár derbies, but they did get beaten by Nagybánya.

Four players got redirected from CFR to U for the next season: Ciocan, Manu, Liviu, and Batacliu. Evidently, U was able to get back into the first division at the end of the that season. Nagybánya was coached by Viorel Matianu at the time, who had been a player for the Kolozsvár U 15 years prior. It was rumoured that U sabotaged CFR’s promotion on purpose.

It was quite a rivalry…

Indeed. The players of the two teams sat at the same table at eateries if they happened to meet each other in the city. However, on the pitch, there was no mercy, they were very tough opponents.

We have spoken about the chauvinism that was a characteristic of Romanian communism above. Have you ever been discriminated against for being Hungarian?

My Kolozsvár-native teammates never held it against me that I was Hungarian. However, there were some in the team who only played there as part of their mandatory military service. They were just conscripted to serve in Szamosújvár (Gherla), and thus they trained with and played for CFR. This worked out the best for everyone, for the conscripts and the club as well. They were from other parts of Romania, it was a different case with them.

In 1985, for example, when Videoton (the football team of Székesfehérvár, Hungary) had a deep run in the UEFA Cup, I was already on the adult team. When Fehérvár got beaten 3–0 by Real Madrid at home, I was greeted by a white cross chalked on indigo in my locker. I still don’t who did it to this day, but I am sure it was one of my Romanian teammates who wanted to make sure ‘I know my place’.

This also happened in 1985: we were playing in a regional final with the youth team against Domavátra (Dorna Vatra) in July. The Romanian referee stopped the game and warned us that if we kept talking in Hungarian with our Hungarian teammates, he would send us off.

This was a time when it was difficult to remain human in Romania, let alone if you were Hungarian.

Let’s talk about the ‘breakup’, your farewell. Why did you leave ‘the Railwaymen’?

I was already asked to play for the third-division Motor Ira in Kolozsvár after my aforementioned injury and subsequent exclusion from the team. I was at two of their training sessions, and I was told they need me. I asked my father to talk to CFR coach Marius Brătannal, but ‘the boss’ did not want to let me go. But my dad was stubborn, he told him that I was his son and I did whatever I wanted. That’s how I got to Ira in 1986.

I came at the same time as Attila Marton, with whom I played in the same youth league winning team. The Motor Ira squad at the time had at least five other ex-CFR players (Login, Ciglenean, Kelemen, Böndi, and Sipos). In the summer of 1986, two of my other youth teammates transferred there (Mayer and Cucuruzan), since Coach Pista Nagy became our head coach, who had trained all of us prior.

You had quite a respectable career, in a hellishly difficult world, under an oppressive regime. However, I still sense there is something lacking there: it was too short. Could it have worked out differently, better for you?

My father, when I got to the adult team, tried to help me get ahead and stay among the best by offering pálinka and gas—which were used as currency at the time—to the coaches in 1985. I told him, however, that if I find out that I was given an opportunity due to nepotism at any time, I would quit playing football. In retrospect, I regret that, this could have turned out differently—I certainly had the talent and the heart for it…

***

All the photos in the article have been kindly provided by István András Kiss.

Related articles: