The following is a translation of an interview written by Gergely Szilvay, originally published on Mandiner.hu.

How does Croatia compare with us today? What are Croatian sensitivities towards Hungarians, and why do they still like us to the present day? Who are our common heroes? Read Mandiner’s in-depth interview on Croatian–Hungarian relations with historian Dénes Sokcsevits, whose book on the history of our southwestern neighbour was recently published.

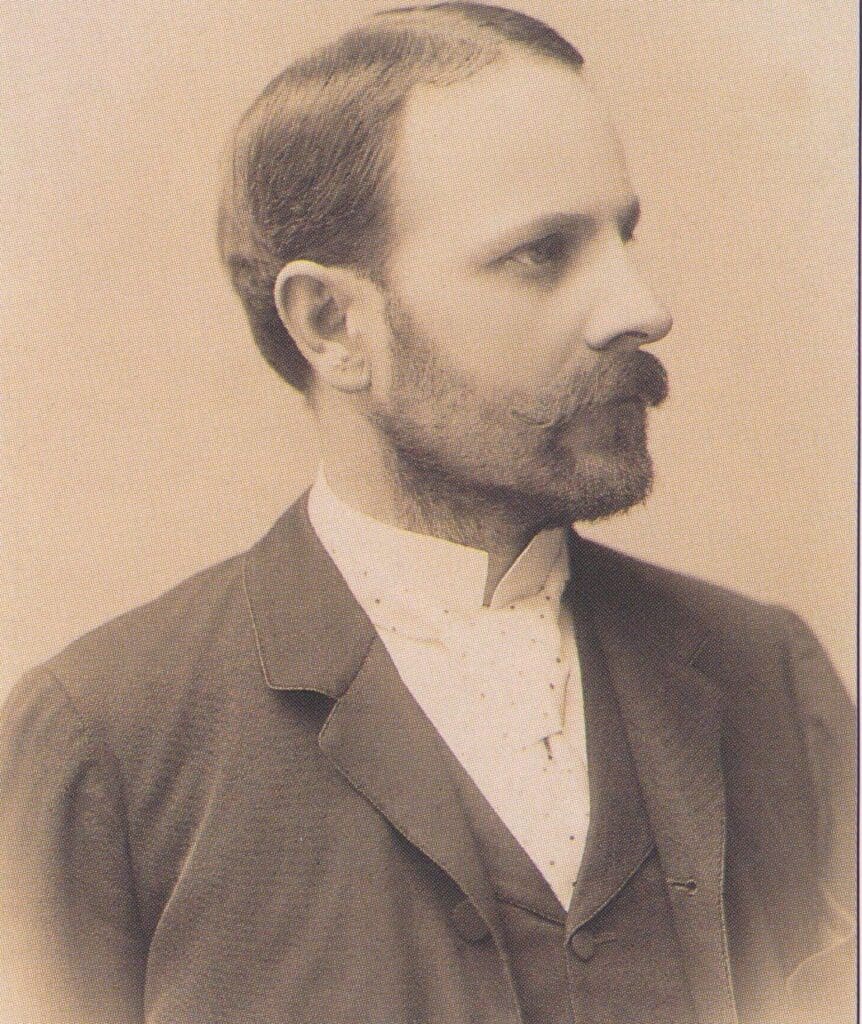

Dénes Sokcsevits (b. Baja, 1960; Croatian: Dinko Šokčević) is a Hungarian Croatian historian and associate professor. After finishing elementary and secondary school in Budapest, he studied Serbo-Croatian language and literature in Novi Sad, Serbia, and then continued his studies in art history and archaeology at the University of Zagreb. He graduated in 1987. In 1991, he became a journalist for the then-weekly newspaper of the Southern Slavs in Hungary Narodne Novine, and in the same year, he started working at the Faculty of Humanities of the Janus Pannonius University of Pécs, where he headed the Croatian Department and the Slavistics Institute. In 1999, he obtained his doctorate in history, his dissertation being on the Croatians’ image of the Hungarians in the dualism period. In 2008, he was elected Director of the Institute of Slavistics at the University of Pécs. From 2014 to 2017, he was the first director of the Hungarian Institute in Zagreb, and also an embassy counsellor. From 2013 to 2020, he was a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of History of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, then at the Rubicon Institute, and is currently a Senior Research Fellow at the HUN-REN Research Centre for Natural Sciences. He has published several books and articles in Hungarian, Croatian, and English.

***

How much of a powder keg are the Balkans today?

Not as much as it was thirty years ago. The situation is much calmer now. Despite the war rhetoric sometimes used by Balkan leaders, they all still remember the Yugoslav Wars, and nobody wants to fight again.

What is Hungary’s Balkan policy like now?

It is very active, both politically and in terms of investments, but also in cultural relations. In the last decade, the Hungarian government established several cultural institutions in Ljubljana, Zagreb, and Belgrade.

Your volume on the history of Croatia has recently been published. How much do you think Hungarians know about Croats and vice versa?

Not enough, but there is great interest in the subject. This is actually the second edition of this volume; the first one was published in Budapest in 2011, then in Croatian in Zagreb in 2017. This second Hungarian edition is a special initiative of the Hungarians in Zagreb because they need it very much in arguments with their Croatian acquaintances, colleagues, and friends. Thus, the new edition was launched by the Endre Ady Zagreb Hungarian Cultural Circle and was published there in three hundred copies, so it is essentially out of print now. A new edition in Budapest would be much needed.

What do Hungarians in Zagreb argue about with their Croatian friends?

First of all, about the past, about the events before 1918. There are points of contention in the history of the polity of the two countries that were judged differently by Croatian and Hungarian public opinion at the time, and after 1918, they were judged differently by Croatian and Hungarian historiography, too.

What is the Croats’ image of Hungarians today?

The Croats’ traditional image of Hungarians was positive until the 19th century.

This can also be seen in literature, whether in folk heroic songs, where Hungarian and Croatian warriors fighting against the Turks are praised as heroes, or in fiction—just think of the Zrínyi family. The conflicts began with the 19th-century Illyrian movement. Indeed, in this period one cannot speak of Hungarian–Croatian relations alone, as Vienna cannot be left out of the picture either. The Illyrian Party relied on Vienna to be active in politics against the Hungarian reformist opposition. It is important to note, however, that there was a serious pro-Hungarian party as well. In 1848, Josip Jelačić was the main character on the Croatian side, but then the Croats were very disappointed after 1849 because they too were caught up in neo-absolutism and did not convene the Sabor (editor’s note: the Parliament of Croatia), for instance.

Therefore, from 1860 onwards, the pro-Hungarian movement was revived in Croatia, so much so that the Croatian–Hungarian Settlement came into being in 1868, which defined the two countries’ relationship for fifty years. Croatia was granted broad autonomy, but despite the proposal of Ferenc Deák, ‘the Wise Man of the Nation’, it was not granted total financial independence. Contrary to Deák, neither Prime Minister Gyula Andrássy nor Finance Minister Menyhért Lónyay proposed it, and the former did not go through with it only because all but three members of the twelve-member Croatian delegation were frightened by the prospect and eventually backed out. Unfortunately, this later became a source of much strife, with Budapest being blamed for fifty years in tax matters.

I guess the two main controversial figures among Hungarians and Croats are Jelačić and Kossuth.

Jelačić will never be a positive figure in Hungarian history, but the Croats saw him as the defender of Croatian independence. Not everyone, though: the Party of Rights considered him a man of Vienna. In 1866, the famous statue of Jelačić was erected in Zagreb, but the communists removed it in 1945, which made him a victim of communism in the eyes of the Croatian public. It is no wonder, therefore, that in 1990 the statue was restored by popular consent, although his sword is not pointing towards Hungary for ‘spatial planning reasons’ today.

And what about Kossuth?

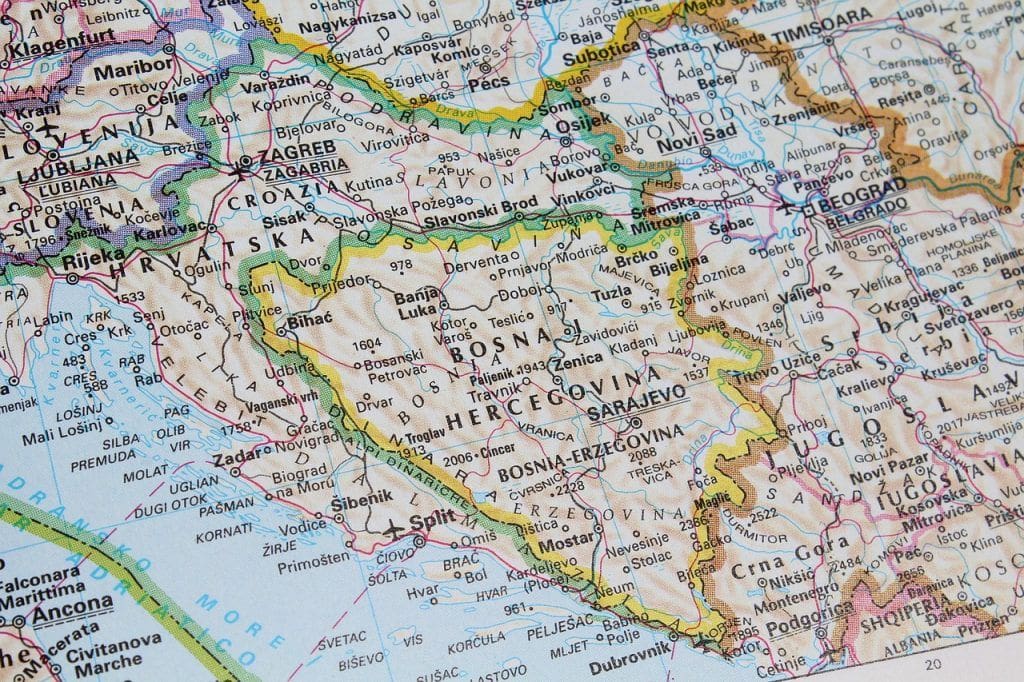

Second Prime Minister of Hungary Louis Kossuth refused to recognize Croatian aspirations for independence. Croatia had a very specific spatial development after the Turkish period. Prior to the Ottoman conquest, medieval Croatia existed more on the seabed, at least under the name of the Kingdom of Croatia. Present-day Zagreb and northwest Croatia were then known as Slavonia. The Croatian nobility fled from the Turks to Slavonia, because the Turks occupied only a small part of it, unlike maritime Croatia. In essence, the country moved away with Slavonia shifting further east, to where it is today. However, the Croatian nobility did not give up on Dalmatia either—they always felt it belonged to them.

The Croatian nationalist aspiration was to unite the three provinces under the name of the Triune Kingdom of Croatia,

which Kossuth refused to acknowledge and argued that Croatia did not in fact exist, because it had been partially occupied by the Turks, and Dalmatia had been the property of Venice until 1797, after the fall of which the Habsburgs did not unite it with the Hungarian Crown and Croatia that belonged to it, but rather governed it separately, directly from Vienna. Furthermore, part of the remaining Croatian land was a military border region. In other words, Kossuth meant what he said in terms of public law; however, in Croatian public opinion, it was as if he had said that he had not been able to find Croatia on the map, which left a bad taste in Croats’ mouths to this day. In contrast, it is not mentioned that later Kossuth, in his emigration, offered Croatia full autonomy.

Further grievances on the side of the Croats are linked to Count Károly Khuen-Héderváry, the Ban of the Kingdom of Croatia–Slavonia, whom we don’t really keep track of.

Yes, the Ban played a much smaller role in Hungarian history than in Croatian, since he was the former Croatian Ban for twenty years, from 1883 to 1903. At that time, from the 1880s onwards, there was an anti-Hungarian movement among the Croats, according to which the tax burden was too high, and there was also a language dispute. The Croats had full autonomy linguistically, they even spoke Croatian in the Hungarian parliament. Correspondence between the two sides was conducted in their own languages, and when they met personally, they spoke German.

However, Prime Minister Kálmán Tisza enforced Hungarian language signs in the joint institutions, thanks to which a scandal broke out, in which Franz Joseph also sided with the Croats. Military force had to be used, and after that, no one would accept the position of Ban. Tisza had four candidates, and although the Croats considered Khuen-Héderváry to be his man, he was in fact the Emperor’s candidate, and he was not even on good terms with Tisza at the time, supporting the opposition in parliament. Khuen-Héderváry was proposed to Franz Joseph by Austro–Hungarian statesman Béni Kállay. According to the Croatian–Hungarian Settlement, one could become a Croatian ban on the proposal and with the countersignature of the Hungarian prime minister, but in reality, all the important Croatian bans of the time were the Emperor’s men, such as, besides Khuen-Héderváry, Ivan Mažuranić or Pál Rauch.

And why is Khuen-Héderváry a negative figure in Croatians’ eyes?

Khuen-Héderváry’s main task was to crush the Croatian anti-dualism movement, the oppositionist Party of Rights. He succeeded in doing so, using the same methods that Tisza used against the Hungarian opposition. Incidentally, he was from an Austrian family, born in a town of rich springs in Moravia, and his family had estates in Slavonia. At the same time, he learned Croatian well and studied at the Zagreb Law Academy, which is why he was chosen as ban. Otherwise, he invested a lot in development and culture: at the time, Croatia was also benefitting a great deal from the boom throughout the Monarchy, with economic development beginning in the 1890s and continuing until the outbreak of the First World War. He was the one building the Croatian National Theatre in Zagreb, and it was under his leadership that the Lower Town of Zagreb was erected. This, however, has been ignored by Croatian historiography and economic history for a very long time; it has only recently been acknowledged by a Croatian economic historian. At the same time, however, the fact that he suppressed and controlled the opposition so harshly has led to a very negative image of him in Croatian public opinion.

As far as I know, the last big insult was the command language of the Hungarian State Railways (MÁV).

This became a real scandal in 1907, but the problem continued throughout the dualism era as well. In principle, the Croats had full linguistic autonomy—Deák even said during the settlement negotiations that it was so natural that it did not even need a law, but the Croats insisted on it, and as it turned out, they were right to do so. The command language of MÁV was decided to be Hungarian, and when the Croats objected to this, Kálmán Tisza’s government argued that MÁV was a private state company that could not be ordered around and that it was an internal company matter. In other words, they circumvented the Croatian–Hungarian Settlement. This would not have been a problem if the official language had been Hungarian only in the upper management bodies, but unfortunately, the conductors and the cashiers were very often Hungarian, too, because the Croats did not speak Hungarian, Hungarian was not a compulsory language in Croatia, and there was no Hungarian-language education in Croatia. In the 1890s, a department of Hungarian Studies was established in Zagreb, but it had very few students. In 1910, only two per cent of the Croatian population spoke Hungarian, but even that was not certain. Thus, conflicts with the train staff were a daily occurrence.

In 1905, there was a pro-Hungarian turn by the Croats, which was only a tactical turn because they wanted to stop the German Drang nach Osten, or the eastern expansion, by uniting the southern Slavs and allying with Budapest as the lesser evil, and later to detach from Hungary as well. The Croatian–Serbian coalition, however, had a disagreement with the coalition government in Budapest over the railway command language law precisely in 1907. The law and the railway pragmatics were introduced by Ferenc Kossuth, son of Louis Kossuth, who had otherwise the best relations with the Croatian–Serbian Coalition, but whose leader was a Serb under the orders of the Prime Minister of Belgrade. Once the coalition had given in to Franz Joseph, Kossuth found the Croatian partners uncomfortable, and, in my opinion, that was his way of getting rid of them. In 1912, the Croatian Constitution was suspended and by 1914 relations reached a low point. In essence,

it was only after 1990 that Croatian–Hungarian relations took a positive turn.

The historiography of the Yugoslav period and the image of Hungarians were all determined by these ordeals.

Is the revival of good relations due to the fact that Prime Minister József Antall sent a shipment of Kalashnikovs to the Croats?

Partly, but others sent weapons, too. Antall may have considered that a strong communist-led Yugoslavia posed a great threat to Hungary, and therefore supported Slovenian and Croatian independence aspirations. In diplomatic relations also, the Antall government supported Croatia in every existing European forum. This happened again later when the second Orbán administration provided enormous assistance to Croatia in its accession negotiations with the EU.

In the 1990s, there was a positive turnaround not only on the government level but also in wider public opinion. In those days, if you spoke Hungarian in Zagreb, you were greeted positively, so much so that even the inspectors on the tram forgave you for playing truant. That’s when the Hungarian department was re-established in Zagreb. Unfortunately, Hungary did not take advantage of this attitude during the Horn government. The first Orbán government already tried, but previously, under Gyula Horn, the wife of the then Hungarian ambassador to Zagreb wrote articles in public daily Népszabadság against Croatian Head of Government Franjo Tuđman, which I think is not entirely in keeping with diplomacy.

Since then, only the MOL case has had negative repercussions: although according to international court rulings, there is no evidence of corruption in MOL’s purchase of the right to control the Croatian oil company INA, Croatian public opinion takes it for granted that there was. However, as I myself experienced as the first director of the Hungarian Cultural Centre (Liszt Institute) in Zagreb, which opened in January 2014, Croats have a positive attitude towards Hungarian culture. The Institute is now ten years old, very active, and there is a huge interest in Hungarian culture.

How much do you think Hungarians know about Croats?

Unfortunately, Hungarians are usually not very well informed about Croatian history, because Croatia is hardly mentioned in textbooks. Yet, there is good cooperation between historians from the two countries, and Croats are genuinely interested in us, although the image of Hungarians in Croatian textbooks still reflects that of older periods, ie it is somewhat negative. We consider the Zrínyis or the Francopans as Hungarians, and they consider them as Croats, although they are our common ancestors, our common heroes. Miklós Zrínyi wrote in the 14th canto of ‘The Peril of Sziget’ about his brother Peter that ‘this valiant brother of mine, both Hungarian and Croatian, truly loves his homeland, for we see it’. Miklós Zrínyi, the hero of Szigetvár, is the protagonist of the Croatian national opera as well. In 1493, at the Croats’ ‘Battle of Mohács’, the Croatian armies were led by a Hungarian-born commander, Croatian Ban Imre Derencsényi. So even among such tragic heroes in Croatian history, there are Hungarians.

How much do Croats know about the Hungarian minority in Croatia?

Due to the war and emigration, the Hungarian minority in Croatia has decreased from 22,000 to barely 10,000. However, it is still represented in parliament: the representative of the Democratic Union of Hungarians of Croatia, Róbert Jankovics, together with his fellow members of other nationalities, contributes to the coalition majority in the Croatian government and therefore plays an important role. Because of this, the Hungarian population became more important than suggested by its its numbers alone. Unfortunately, cultural autonomy is not enough to stop assimilation.

What do Croats think about Croats in Hungary and their situation?

I must say that the Croatian public knows very little about the Croatian minority in Hungary. It is a bit similar to the situation in Hungary before 1990, when a large part of the Hungarian public considered a Hungarian from Transylvania to be Romanian. I went to university in Zagreb, and I could not convince the locals that I was Croatian. Not because my mother was Hungarian, but because all the Croatian nationality scholarship holders from Hungary were simply considered Hungarians.

What is the present state of Croatians in Hungary?

In the last census, we could see that there was a significant decrease in their numbers. This is not only due to simple assimilation but also to the fact that a significant part of Croatian villages in Hungary are located in economically rather passive rural areas. The Drava Region has not been known for its economic development in the last thirty years, and therefore there has been a high level of emigration from Croatian villages in the area. Perhaps that is why the number of Croats has decreased everywhere in the countryside while increasing in Budapest. The system in Hungary is based on minority self-governments, and the National Croat Self-Government has many autonomous institutions. Of all the minorities in Hungary, the Croats were the first to set up their own institution, a publishing company, and they were also the first to take over a minority school.

The Hungarian Government has been on spectacularly good terms with the Serbs for years, just as it was with the Croats in the past when we wanted to help them join the EU. What is the state of Croatian–Serbian relations today?

The Croatian–Serbian relationship is still not completely fine—those thirty-year-old memories are quite vivid even now. Croats are at the height of their emotions when they remember the siege of Vukovar, while every August tempers flare in Belgrade over the departure of Croatian Serbs. In 1995, during Operation Storm, the Croats, led by General Ante Gotovina, retook the breakaway Serb Republic of Krajina, which the local Serbs had previously declared to be a Serbian territory within Croatia. Before the Croatian invasion, the Serbs fled—although there was no genocide, as there was no one left to exterminate, a fact also recognized by the Hague Court in Gotovina’s trial, who was thus finally acquitted. I would add, however, that the Serbs in Krajina, even if they do not live at home, have been receiving Croatian pensions ever since and are regularly going home to vote. Croats who have left Serbia, on the other hand, hardly ever go home anymore. Namely, the issue of war reparations is still on the agenda today. Hundreds of people are still registered as missing, which is a strain on relations, and that is why the Croatian public is obviously not very happy about Budapest being so friendly with Serbia. But at the same time,

official Croatian policy, at least at government level, does not want to create tensions with Belgrade.

Interestingly, it is precisely the relationship between the two Presidents of the Republic that has been strained in recent years. If anything, this has increased the popularity of President Zoran Milanović in Croatian public opinion. There is still some anti-Serb sentiment in Croatia, but now Serbian performers can perform in Croatian cities without any trouble, and there are examples of Croatian artists performing successfully on Serbian stages, too, although I find that the anti-Croatian sentiment in Serbia is a little bit stronger. This is the first time, by the way, that there is also a Croatian minister in the Serbian government, whereas in the last Croatian governments, there were several Serbian ministers.

But Bosnia is still a disputed and fragile country.

The convictions of Croatian politicians and generals in Bosnia by the Hague Court smacks of collective guilt. Under the Dayton Agreement, Bosnia is made up of two member states: the centralized Republika Srpska and the Bosniak–Croat Federation, or the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the latter, Croats feel disadvantaged, and their numbers are dwindling. Thus, Bosnia has deliberately not held a census in recent times.

Lebanon effect?

Yes. For the sake of peace and the status quo, they prefer not to hold a census. There are some international military forces of symbolic number stationed there, and from what I have seen, people there are not keen to go to war again, but the situation itself has not been resolved. The internal situation is unstable, and there are also frictions in relations between the Republika Srpska and the Bosniak–Croat Federation, which of course the Bosnian representative of the international community is trying to influence, to dampen, or sometimes, as I see it, to strengthen with certain measures. But the point is that the internal situation is still unsteady—the Dayton Agreement has not really brought lasting reconciliation. The Croatian government, on the other hand, is trying to support Bosnian Croats, but mainly only in the economic and cultural fields.

Who supports the Bosniaks today? The Turks and the Saudis?

Türkiye and Saudi Arabia were the two countries that supported the Bosniaks the most during and after the war, but it is actually Türkiye that is trying to invest the most in Bosnia’s economy. Saudi Arabia has built a lot of mosques but invests little in the economy itself.

Most of the Hungarian public understands Croatia and Serbia, but I don’t think we know much about how Bosnia got on the map. Could you outline it?

In the early Middle Ages, there were many more small states in the entire southern Slavic region than there are today: there were five or six in what is now Croatia and several in Serbia. Even Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus mentioned Bosnia as a Byzantine, later Hungarian, area of interest already in the 10th century. The state was named after the Bosna River, a tributary of the Sava. By the end of the 12th century, a Bosnian principality was established, not coincidentally, since the ban, the head of a principality, was a vassal of the Hungarian king. Then, over time, the ban became more and more independent, but only towards the end of the 14th century did he take on the title of king. This area was originally part of the Catholic world, but later an organisationally separate church emerged, against which crusades were waged because it was considered Bogomils*. More recent research suggests that there were not actually dualistic heretics in that area, and they did not essentially deviate from Catholic doctrine but were just completely autonomous in ecclesiastical terms. They rather resembled a monastic community because they did not collect taxes. This, of course, made them popular among the Bosnian nobility and the court of the ban, as they were not rivals in taxation. In 1291 and then in 1400, the Franciscans took root in Bosnia, and from then on, the recatholization of the country gradually began—by the 15th century, the majority of Bosnia was Catholic again.

Then came the Ottoman invasion, after which a Southern Slavic-speaking but Islamic population came into existence. The process of Islamization gained momentum in the 16th century, after the Battle of Mohács, and since the country was not seized from the Ottoman Empire during the national uprisings of the early 19th century but was occupied by the Austro–Hungarian Empire in 1878, the Muslim population was preserved. In the other Balkan countries, Muslims were expelled, ie some ethnic cleansing was carried out. In the great national integration efforts of the 19th century, both Croats and Serbs attempted to integrate Muslim Bosniaks, but these ambitions turned out to be mutually exclusive. When Yugoslavia was formed, the integration struggle continued, which

in Tito’s Yugoslavia ended with the Bosnian Muslims being recognized as an independent nation

on an equal footing with the Croats and Serbs. In fact, the name Bosniak, a word of Turkish origin simply meaning the inhabitants of Bosnia, only became official after 1990. However, there is also a Croatian ethnic group in Hungary that calls itself Bosniak.

How is the EU dealing with the Southern Slav question?

As I see it, the EU has not paid enough attention to the Balkans over the last decade, which I consider a big mistake. Firstly, if there is a mess in the backyard, it can also affect what happens in other areas, and secondly, it simply leaves the region untapped. Croatia’s accession to the EU was also very delayed—it was not even admitted together with Romania and Bulgaria in 2007, only in 2013, even though Croatia’s development indicators had already been better than those of the other two countries back then.

Since then, the Balkan enlargement process has been frozen, albeit, as we can see, it is not good to leave a power vacuum. Before the war in Ukraine, the Russians had been trying to connect with the Serbs—they even concluded a partnership agreement, which affects relations between Serbia and the West today, especially now: the Serbs have not joined the EU sanctions either, which is resented by Brussels. Meanwhile, the Chinese are trying to invest more and more in the country economically. So, the EU should care much more about this region.

Overall, how do Croatians compare to us in terms of prosperity and quality of life?

Based on my own experiences, there was a very big decline in Croatia in the 1990s, both because of the war and because of the failure of the socialist economy, but since 2000, the country has been slowly starting to recover from it. Of course, Croatia has also been hit by the world crises, but there has been significant progress in terms of living standards, infrastructure, and economic development indicators recently. I would even hazard a guess that the Croats are already living a little better than we are. The salaries of scientific researchers, for example, are twice as high as ours. So far, Croatia used to be more expensive than Hungary, but now we are unfortunately catching up.

How well informed are Croats concerning Germans?

The German orientation is very important for them. Back then, Croatian independence was supported by Germany the most, albeit it’s not entirely true that it was the Germans who blew up Yugoslavia, as it fell apart on its own, from within, for internal reasons. German and Austrian tourists have always played a very important role in Croatian tourism; although recently they are not the only ones coming. EU accession has also been good for the Croatian economy. Nevertheless, tourism is too heavy, accounting for 20 per cent of the country’s economy, which makes it vulnerable in times of epidemics. But overall, Croats are doing well: no wonder that the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ), the right-wing governing party, is above 50 per cent in the polls. Although many are unhappy with the government, they seem to be dissatisfied with the opposition, too.

How do Croats feel about Brussels?

Most of the time the Croatian Prime Minister takes a pro-Brussels position, but most Croats are rather conservative, and although they don’t have a border fence, it is immensely difficult for an illegal migrant to cross the Croatian border. In other words, they are trying to meet Brussels’ expectations, and at the same time, they are guarding their border very tightly. According to the latest census, for example, the proportion of religious people has fallen in Croatia, too, meaning that modern liberal ideas are spreading there as well,

but the majority still prefer conservative national and moral principles.

What do you recommend reading in Croatian literature, and what should we pay attention to in Croatian culture?

Many outstanding works of Croatian literature were published in Hungarian translation in recent decades, but perhaps because of the strong Hungarian connection of its themes, I would recommend the Adriatic Trilogy of historical novels by excellent Croatian writer Nedjeljko Fabrio, who died a few years ago. The novels—Triemeron, Berenice’s Hair, and City on the Adriatic—have been published in Hungarian in a superb translation by Gábor Csordás. The last one in particular may be of interest to Hungarian readers, as it is actually a novel about Rijeka, also known as Fiume, and most of the book is about the love between a Croatian boy and a Hungarian girl.

Here we are at the HUN-REN Research Centre for Natural Sciences. What does a working day of a humanities researcher look like here?

We don’t have to be here every day; we have two institute days, and we also often go abroad to do research or to give lectures at international conferences and universities. When we are here at our research group on Southeast Europe, we have meetings and discuss each other’s research projects, ideas, and of course the current Balkan politics: Hungary’s Balkan policy, Hungarian Balkan relations, and the relations between the Balkan countries themselves.

*Members of a dualist Christian religious sect that flourished in the Balkans between the 10th and 15th centuries, declared heretical.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.