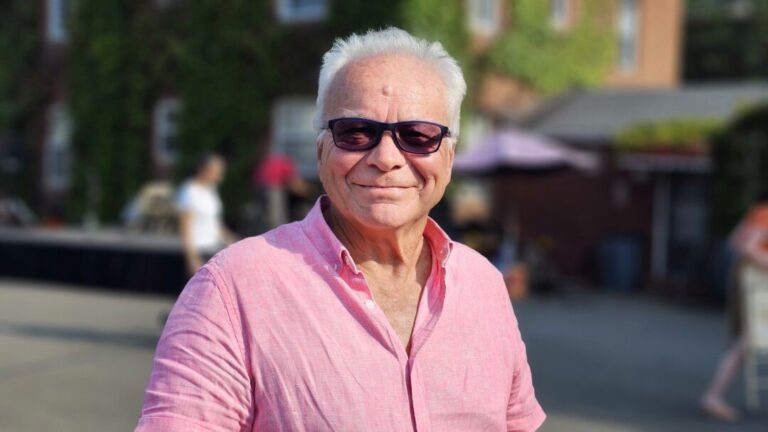

Nicolas Bauer, Senior Research Fellow at the European Centre for Law and Justice (ECLJ), recently attended the Rule of Law as Lawfare conference in Budapest. The event was co-organized by the Danube Institute, the Center for Fundamental Rights, and The European Conservative. During the conference, Bauer gave an interview to Hungarian Conservative, where he discussed the philosophical issues of human rights, the over-politicization of the rule of law and how international courts and institutions are being overrun by biased experts funded by private foundations linked to George Soros.

***

How did we reach the point where unelected bureaucrats use the rule of law as a political weapon against sovereign countries?

The rule of law is supposed to be independent from politics, above politics. There has always been a mutual suspicion between the rule of law and democracy, with the rule of law being suspicious of human rights abuses because of democracy, and democracy being suspicious of the rule of law being too rational and not political enough. However, every actor that has power is a target for political influence. Even though the rule of law is supposed to be independent, it has become a target for such influences. Today, the rule of law is highly politicized.

The rule of law attempts to impose a definition of democracy that

no longer reflects the will of the people or the majority.

Instead, it is based on a substantial definition of democracy grounded in a specific set of values. For example, consider the Council of Europe, which is based on the rule of law, human rights, and democracy. Each time there is a reference to ‘democracy’ by the Council of Europe or the European Court of Human Rights, it no longer refers to the traditional concept of democracy but to a ‘democratic society’, which is said to be based on ‘pluralism’, ‘equality’, ‘tolerance’, and ‘openness’. These values are not intended for discussion but are expected to be accepted by everyone as the foundation of society.

During the panel discussion, the moderator mentioned that he ‘hates human rights’ because nowadays they are interpreted in a completely different way than they should be. What do you think about this statement?

Of course, human rights raise several philosophical issues. They are too individualistic. The individual remains at the centre, and the common goods are no more than a limit to his or her rights and freedom. Freedom is, therefore, not ordained to the common good. The second main issue is the principle of non-discrimination, which applies to gender and religion.

In international conventions, ‘human rights’ are protected, but ‘human’ is not defined. Is a person ‘human’ before birth? The dignity of man, which is the basis of human rights, is not defined either. Is it ontological? Or is dignity related to freedom and autonomy? Similarly, there is a ‘right to freedom of religion’, but there is no mention of what is ‘religion’ and what differentiates ‘religion’ from any other activity. This vagueness gives great power to the institutions that interpret these conventions. It is

up to them to say who is human or not, what is consistent with dignity or not, and what is religious or not.

At the ECLJ (European Centre for Law and Justice – ed.), we do not view human rights as the best system of law but as positive law. We are experts in human rights law, and use human rights to defend victims, just as other stakeholders do.

Recently, Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) Karim Khan asked the ICC judges to issue an arrest warrant for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in connection with crimes against humanity in Gaza. As an expert of human rights, what do you think about this proposal?

These international institutions maintain significant moral prestige. This prestige has a great impact because they are supposed to be above states, above corruption, above sovereignty, and beyond contingencies. However, in reality, this is not the case. If we consider the experiences of the International Criminal Tribunals, the predecessors of the ICC, we can see that they had biased proceedings. For example, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) has been perceived as political because of the past commitments of its judges and collusion with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). There is a gap between this reality and the moral prestige of such an institution.

This gap can also be observed at the European Court of Human Rights, which does not respect the standards it imposes on states. The ECLJ revealed the existence of a structural problem of conflicts of interest within the Court. Similarly, at the United Nations Human Rights Council, some experts receive private funding, which influences their reports.

This funding comes from liberal foundations and NGOs.

For instance, the Former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture issued a report in which he explained that denying a woman access to abortion, as in Poland, is a form of ‘torture’. The Ford Foundation gave him 90,000 dollars to write this report. The Open Society Foundations also gave him 200,000 dollars the same year. These foundations thus paid to promote their ideas with the logo of the UN.

These experts are being paid by private foundations, much like Brussels bureaucrats who are funded and positioned with the help of certain foundations. How can this trend be reversed? How can sovereign nation-states protect themselves against these processes?

At the ECLJ, we aim to expose these dysfunctions within international institutions. Until about four years ago, we had never focused on this aspect. We centred our work on public policy arguments and issues such as abortion, religious freedom, or freedom of expression. However, we eventually observed biases in how international institutions made decisions. The first step is exposing these issues, which provides states with useful tools when they want to resist international institutions.

For example, after we began this work, some states started to argue during proceedings at the European Court of Human Rights: ‘We don’t want this judge to be part of the panel for this case because he founded and ran the NGO which lodged the application to the Court.’ Our reports thus

helped states avoid biased judgements,

thereby improving the functioning of these institutions to meet the minimum criteria of justice.

However, international institutions do not have an executive branch or an army; they rely on states to cooperate and engage in dialogue. States are free to reject decisions or judgements that are inconsistent with the treaties they signed. I believe governments should act as stakeholders to help reverse this trend. There is thus a democratic aspect, which depends on politicians and elections. One model for this is Hungary. As Viktor Orbán said, we conservatives must not ‘resign ourselves to our minority status but play to win and proclaim the Reconquista.’

Related articles: