‘A Nation of Immigrants’—comes the frequent four-word rebuttal to the American right’s calls for stricter immigration enforcement. It is easy to include in cute little graphics and awkward memes to circulate among leftist circles on social media, shared by people who are convinced they just summarily shut down one of the major agenda points of the other side.

This type of discussion sometimes bleeds into European politics as well, with certain factions of the left wanting to see masses of migrants being let into the European Union.

A Nation of Immigrants is the title of a 1958 book authored by then-Senator and future US President John F. Kennedy. Those who like to use it today typically do so to imply that there had been a historic appreciation and approval of immigrants coming into the United States, either by the political leadership or the general populace, since the founding of the nation. Therefore, those who are against foreigners coming now are going against the ideals of the early Americans.

A more generous interpretation of the phrase is that even if there was opposition to mass migration among the early citizens of the United States (which there was, as we will elaborate on later), the immigrants coming in made the country what it is today, and that is why immigration en masse should be supported to this day.

The adherents of this interpretation tend to think of early American settlers as immigrants. However, at the time,

the settlers most likely thought of themselves as British subjects from mainland England and Scotland—then, after 1707, Great Britain—travelling from one part of the British Empire to the other.

The Crown claimed the colonies in North America as soon as they were established in the early 17th century.

The early colonizers certainly did not think there was a sovereign nation where they were about to settle, with immigration laws on the books that they would have to knowingly violate to get in—unlike the illegal immigrants trying to get into the United States today, mostly through the southern border shared with Mexico.

Another issue with this line of thinking is that it equates the early British settlers with Americans, as in the political leadership and the citizens of the United States of America. I personally believe it would be better to start the historical overview of US immigration with 1787, the year of the Constitutional Convention.

Within three years of the Convention, the newly founded country of the United States passed its first law about acquiring citizenship. The Naturalization Act of 1790 called for only ‘free White person(s)…of good character’ to be eligible for US citizenship—which, evidently, is morally wrong. However, it also shows that the Founding Fathers did not intend to let every new arrival become a full-right member of the new nation without preconditions, like what modern pro-immigration advocates like to push for.

Those Founding Fathers, by the way, were all born within the bounds of the British Empire. They were all English-speaking white men of European heritage, and almost all Protestant. That is not to say that there is a moral virtue in ethnic hegemony. However, this does disprove the notion that the United States was a diverse, progressive country, welcoming of all people since its creation.

The one outlier example of the diversity of early American leadership would be 8th President Martin Van Buren (in office 1837–1841). He was the first POTUS to be born in the independent United States (born in 1782 in Kinderhook, New York), and he is also the only president to not speak English as a first language. Van Buren came from a Dutch settlement in New York, and thus his native language was Dutch.

The first wave of immigrants of noticeable magnitude came to the US in the 1840s.

The potato famine in Ireland prompted many of the struggling Irishmen to travel across the ocean, searching for a better life in the New World.

The Irish were predominantly Catholics, as opposed to the mostly Protestant American population, which led to anti-Catholic sentiments that played a role even as recently as the 1960 election, when John F. Kennedy from the Democratic Party became the first Roman Catholic president elected in the US.

In response to the wave of Irish immigrants, the Native American Party was founded in 1844 with a single agenda point: opposing Catholic immigration. Evidently, they were not using the term ‘Native American’ in the sense it is most often used today, in reference to the indigenous tribes living in North America before the establishment of European settlements. They were referring to the native-born people of the United States of America.

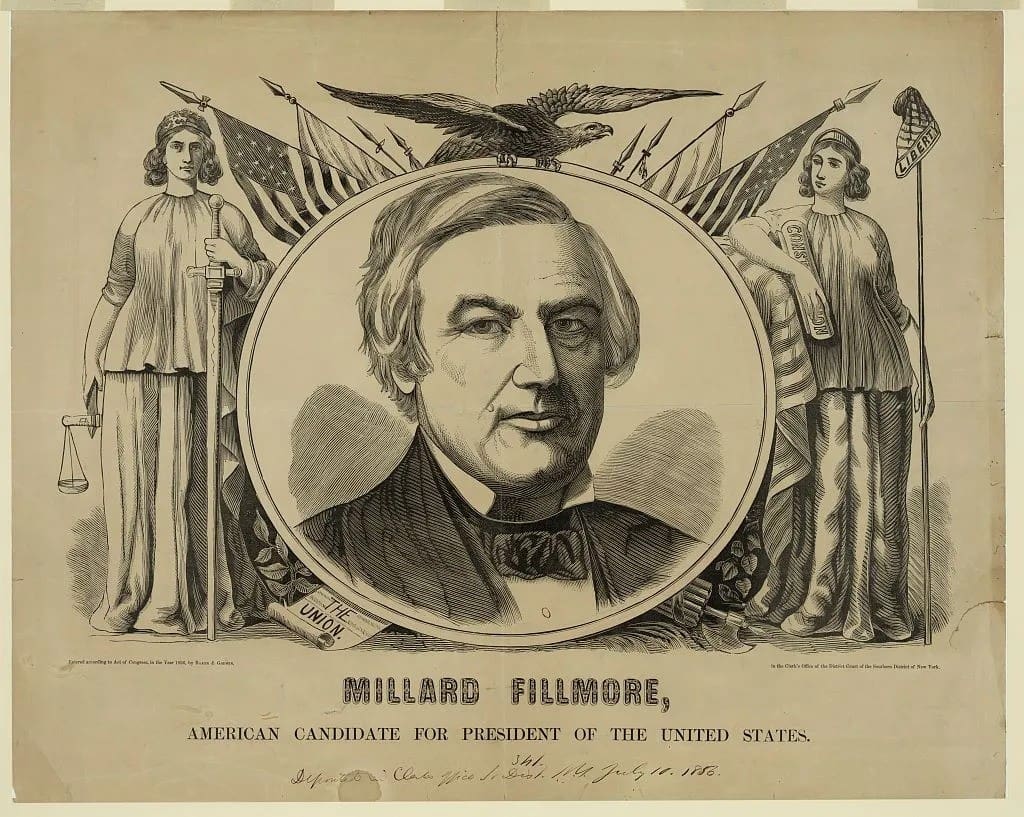

In 1855, they changed their name to the American Party. However, they were better known colloquially as the ‘Know Nothing Party’. They achieved their best result in the 1856 presidential election, when they got 21.6 per cent of the popular vote. They also got eight electoral votes after winning the state of Maryland. That year, Former President Millard Fillmore (who was in office as a member of the Whig Party in 1850–1853) led their ticket. Interestingly, he got the American Party’s nomination without campaigning for it. In fact, he was in Europe while the nominating convention took place.

All this is to show there has been a level of objection by the general populace to migration into the US ever since it became an issue of any significance.

Let me say that again: that is not to say that objection to immigration is morally right per se. However, it does prove that those who try to argue for mass migration by appealing to the alleged historic ideals of early America are wrong.

Another mantra that is often brought up is the few verses of a poem written on a plaque on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty. The poem The New Colossus was written by Emma Lazarus, and originally published in Joseph Pulitzer’s newspaper called New York World, as part of the effort to raise funds from the public to erect the very same pedestal where it is now, placed there in 1903.

The famous words of the few lines of the poem are:

‘Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.’

This poem was written in 1883. The Statue of Liberty was erected in New York City, New York in 1886. In that same decade, the 1880s, the US saw its first significant wave of non-European migration, out of China.

In 1882, Republican President Chester A. Arthur signed into law the Chinese Exclusion Act,

banning the migration of Chinese people (with the exception of merchants, teachers, students, travellers, and diplomats) for 10 years. The law was renewed in 1888, before the 10-year period even expired, by President Grover Cleveland from the Democratic Party.

Again, those who point to the poem on the Statue of Liberty pedestal as evidence of a historic approval of mass migration in 19th-century United States are incorrect. Presidents of both major political parties took drastic measure that would certainly be deemed ‘racist’ and unacceptable by today’s standards to limit foreigners coming into the country.

The idea that we should welcome masses of foreigners coming into our countries, often even by disregarding immigration laws, is fairly new—and not easy to argue for in any sincerity.

Related articles: