While the United States considers China an adversary, most EU countries have a more nuanced relationship with Beijing. As the EU’s own factsheet on relations between the Union and China noted last year, despite disagreements and conflicts, ‘the EU has remained committed to engagement and cooperation given China’s crucial role in addressing global and regional challenges. In that regard, the EU’s current approach towards China set out in the “Strategic Outlook” Joint Communication of 12 March 2019 remains valid. The EU continues to deal with China simultaneously as a partner for cooperation and negotiation, an economic competitor and a systemic rival.’

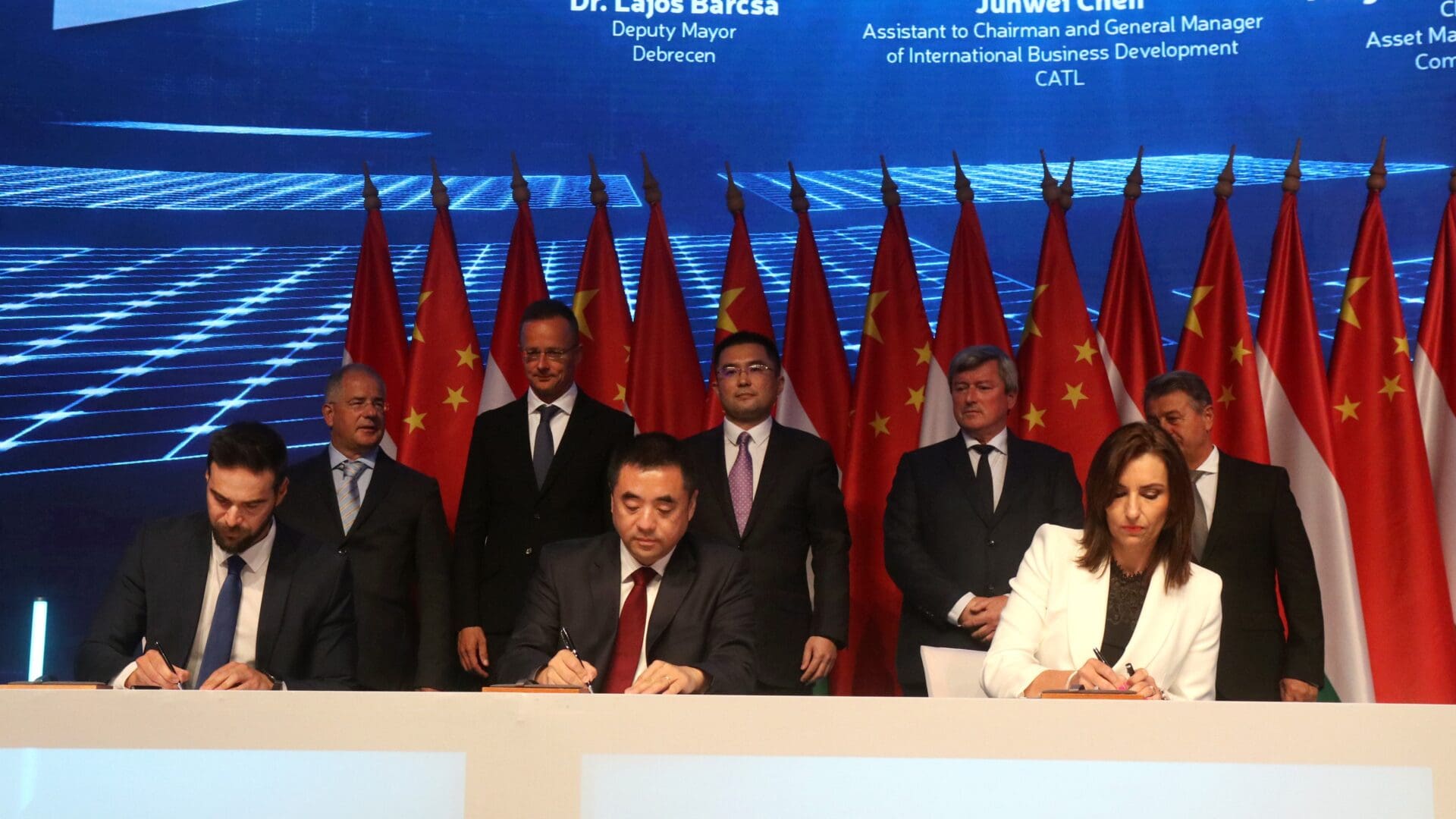

As far as Hungary is concerned, Sino-Hungarian relations are informed by the Orbán government’s non-ideological approach as reflected in the Opening to the East policy. The past decade was characterised by increasing mutually beneficial economic cooperation between Beijing and Budapest. The most recent milestone in Chinese-Hungarian economic cooperation was the Chinese battery manufacturing giant CATL’s announcement to invest in Hungary. CATL’s investment was the single largest Hungary secured in 2022. The 3 trillion HUF investment is going towards a giant battery manufacturing plant in Debrecen. The batteries will be used in electric vehicles, therefore, CATL’s project is linked to BMW’s plans to set up an assembly facility in the same town. CATL’s plant will be able to provide batteries to 2 million new cars a year and employ around 9,000 people. By 2030, when the plant will reach its full capacity, Debrecen alone will rival every European country in battery production, except Germany. The investment contributes to Hungary’s green transition as well.

Both some civil groups in Debrecen and several opposition parties have voiced concerns about the possible negative environmental impact of the new factory. While these worries and fears should not be dismissed, and merit to be addressed by experts and policy makers, all considered, with the gradual phasing out of internal combustion engine-propelled cars in the EU, the future is that of electric vehicles, which need batteries. It is certainly wiser to produce those batteries locally, creating jobs and economic revenue for the country, than to idly watch others, like Germany, jump on the EV bandwagon. As Reuters reported just the other day, ‘Politics aside, China’s CATL ramps up cell production in Germany’ in the small town of Arnstadt. Alternatively, the batteries for the electric scooters that some Hungarian politicians like to ride would be manufactured in some far away country where the locals would be paid extremely low wages, and the batteries would then have to be shipped back to Europe, resulting in huge externalities, but that would clearly not bother those who would want to see the Debrecen project scrapped.

But the Debrecen investment is not the only major Chinese project in Hungary. Cargo transport at the Budapest Liszt Ferenc International Airport was also rapidly boosted by Chinese investments. For instance, Alibaba, one of the world’s largest online shops, has chosen Hungary as its Central European headquarters. While in 2015, only 80-90 thousand tons of goods went through the cargo section of the Budapest Airport, in seven years, by 2022, the volume of goods handled at the airport has increased to 200 thousand tons a year. For comparison, 270 thousand tons were handled back in 2015 at the Vienna airport, which declined to 240 thousand tons by 2022. The growth that Budapest Airport has experienced over the last seven years made it the most dynamically developing airport in the region. Neither the pandemic nor the current worldwide economic turbulence stopped it from increasing the volume of goods handled there. As a result of the rapid growth, millions of goods are now being handled and sorted monthly in Budapest just by Alibaba.

Other than the rapid development of the Budapest Airport, which is partially a result of Chinese investment,

another major project backed by Chinese investors is the Budapest-Belgrade high-speed train.

The high-speed train long in the making would cut the time needed to reach Belgrade from Budapest in half, to 3.5 hours. It is a part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Europe. The easier travel route between the two capitals is expected to increase the number of yearly passengers from 3 million to 9 million. The currently existing railway line between Budapest and Belgrade, which goes further south to Greece, has not been renovated in the last 40 years. In 2013, however, the two countries signed an agreement to renew the line, with the help of Chinese capital. Serbia’s share of the project (between Belgrade and the Hungarian border) is already finished, while Budapest promised to finish the remainder of the tracks by 2025.

So criticisms of Hungary-China relations that describe them almost as a love affair should be taken with a grain of salt, to say the least. China’s willingness to use investments and economic ties to expand its influence is no secret, and there are high profile debates about that in the country. The existence of a political discussion and civil society reactions (for instance, the protests against Fudan University’s plans to open a campus in Budapest) show how the Hungarian political discourse is also in the process of negotiating the benefits and trade-offs of Chinese investments. While critics accuse the Hungarian government of allowing for too much Chinese influence in the country, the very existence of a political debate on China demonstrates that Budapest belongs to the Western bloc—the country would not weight the pros and cons of Chinese investments if it was ‘captured’ by Chinese interests as claimed by critics.

Hungary’s alliances are clear: it is a member of NATO and the EU. While Chinese investments contribute to the economic diversification of the country, they do not alter Budapest’s political and diplomatic commitments. A medium-sized country like Hungary is more exposed to external economic impacts than larger nations. Currently, Hungary is greatly dependent on German investments and firms. Such dependency is convenient politically, as Germany belongs to the same political bloc, but it also comes with a risk of economic turbulence if Germany experiences a major economic downturn. Diversifying the economy by, for instance, allowing for Chinese investments may mean more economic stability in a crisis situation. In other words, it is not political (as claimed by critics), but economic considerations that led to the formulation of Hungary’s Opening to the East Policy which also opened new avenues for boosting economic ties with China.