In his extraordinary summer address at Tusványos this year, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán made a profound aside from the main geopolitical themes of his talk. He said:

Here we must talk about the secret of greatness. What is the secret of greatness? The secret of greatness is to be able to serve something greater than yourself. To do this, you first have to acknowledge that in the world there is something or some things that are greater than you, and then you must dedicate yourself to serving those greater things.

There are not many of these. You have your God, your country and your family. But if you do not do that, but instead you focus on your own greatness, thinking that you are smarter, more beautiful, more talented than most people, if you expend your energy on that, on communicating all that to others, then what you get is not greatness, but grandiosity.

And this is why today, whenever we are in talks with Western Europeans, in every gesture we feel grandiosity instead of greatness. I have to say that a situation has developed that we can call emptiness, and the feeling of superfluity that goes with it gives rise to aggression. Hence the emergence of the ‘aggressive dwarf’ as a new type of person.

I don’t know if the prime minister has ever read Dante, but this very same truth is taught by the great Tuscan poet in his Divine Comedy,

or Commedia, published almost 700 years ago.

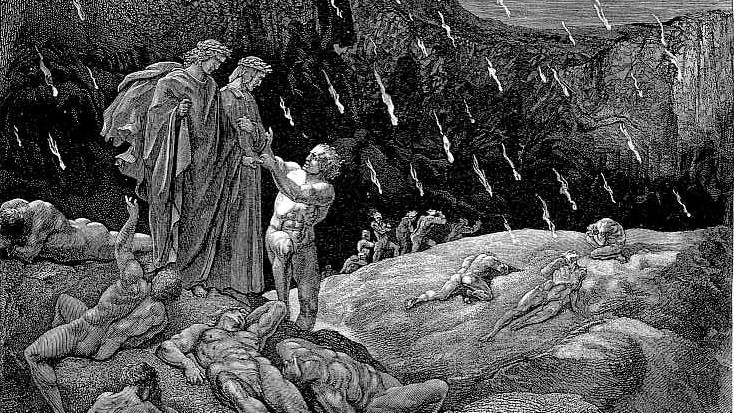

The poet Dante wrote the three-volume poem—Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso —after his abrupt and painful exile from his native Florence. The poem is an imaginative journey through the afterlife made by a pilgrim named Dante, accompanied first by the classical poet Virgil, and then by his true love, Beatrice. The Commedia is a political and social commentary on Italy in his era, a deep exploration of human nature and fallibility, and a relentless inquiry by the author into his own failures that contributed to his fall from grace.

What was that fall? By the year 1300, Dante Alighieri was an important man in Florence. He was an accomplished poet who had been appointed to the council that governed the city. Yet he found himself on the wrong side of cutthroat Italian politics, and exiled from his city for good. He lost everything. The Commedia emerged from Dante’s attempt to make sense of his experience of catastrophic loss.

The pilgrim Dante’s journey through Hell (Inferno) serves to make him sensitive again to the reality of sin. At one point, Dante and Virgil arrive at the place where the ‘Sodomites’ —the old-fashioned term Dante uses for ‘homosexuals’ —are punished. The Sodomites run ceaselessly on a hot, dry desert plain. This symbolizes the infertile character of their lust. To Dante, a medieval Catholic, homosexual behavior was a sin against the natural order, as sex is meant to produce new life.

Sex does not come up in the pilgrim Dante’s encounter with one of the damned. Rather, sodomy in the Inferno stands for wasted potential. We see this when the pilgrim Dante meets his former mentor, Brunetto Latini, who has been condemned to the Circle of the Sodomites.

Brunetto was a great intellectual and cultural figure of the late Middle Ages. In the poem, Dante and Brunetto meet as father and son. The pilgrim Dante is moved to see his teacher again, and the feeling is mutual. Brunetto advises Dante:

If you pursue your star,

you cannot fail to reach a splendid harbor,

if in fair life, I judged you properly…

(Inferno, Canto XV:55-57)

This is the kind of advice one hears at a graduation address: follow your dreams, young people, and you will reach your glorious destination. But it is a trap.

In the Commedia, the stars symbolize God’s watchful presence. Navigators plot their courses by the stars. In this encounter, Brunetto tells Dante that the purpose of writing is to win worldly fame, and that he should choose his path through life by the light not of God or of any higher values, but of the burning desires in his heart.

At this point early in his journey, the pilgrim Dante is so moved by his reunion with his mentor that he doesn’t seem to notice that the old man is in Hell, and is therefore not a reliable adviser. Dante thanks him for his good words, and moves on. The reader, though, understands that Brunetto’s sexual sin stands for a deeper sickness of the spirit—one that has rendered Brunetto’s writing sterile.

Brunetto is a vain man, a writer and public intellectual who thought the way to pursue immortality was to serve his own cause in his work. Brunetto’s sodomy symbolizes a misuse of his God-given generative powers—that is, Brunetto’s misuse of his creative abilities as a writer and artist. To create only for the sake of magnifying your own fame and success in the world is, spiritually speaking, a sterile act.

As far as we know, the poet Dante never faced the temptation to have sex with men, but as we see here, his beloved mentor Brunetto attempts to seduce Dante into a kind of artistic and intellectual sodomy: pursuing literary greatness for the sake of serving oneself, of satisfying one’s own urges.

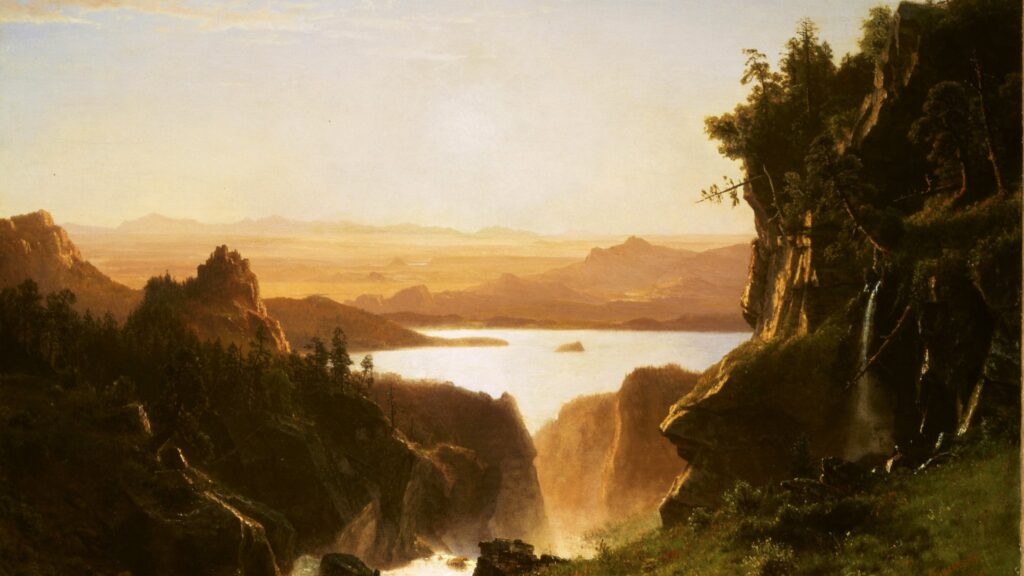

In the next book of the Commedia, called Purgatorio, the pilgrim Dante comes to greater wisdom when he meets the shade of the painter Oderisi of Gubbio. Oderisi had been one of the greats in his day, and confesses to the wayfarer that in life, an overwhelming desire to greatness had seized his heart. This, he says, would have landed him in the Inferno if he hadn’t turned to God before he died.

In contrast to Brunetto, who counseled Dante to write for fame and glory, Oderisi tells the wayfarer that artistic greatness is fleeting:

O empty glory of the powers of humans!

How briefly green endures upon the peak-

unless an age of dullness follows it.

In painting Cimabue thought he held

the field, and now it’s Giotto they acclaim-

the former only keeps a shadowed fame.

So did one Guido, from the other, wrest

the glory of our tongue-and he perhaps

is born who will chase both out of the nest.

Worldly renown is nothing other than

a breath of wind that blows now here, now there,

and changes name when it has changed its course.

Before a thousand years have passed-a span

that, for eternity, is less space than

an eyeblink for the slowest sphere in heaven-

would you find greater glory if you left

your flesh when it was old than if your death

had come before your infant words were spent?

… Your glory wears the color of the grass

that comes and goes; the sun that makes it wither

first drew it from the ground, still green and tender.’

(Purgatorio XI: 91-117)

‘The lesson is this: fame comes and goes in a flash.’

The lesson is this: fame comes and goes in a flash. If you seek achievement only to serve yourself, you will be forgotten.

The only achievement that may last is found in works and deeds done for the greater glory of God, or something higher than oneself. The poet Dante, through the words of Oderisi, says that the same sun that draws forth the creative urge in the form of eros will cause that desire to wither if it does not bear fruit.

This is the lesson of the Sodomites in the Inferno. Though we may be certain that a medieval Catholic like Dante did not hold modern liberal opinions about homosexuality, it seems that he employs homosexuality in the Commedia more as a symbol of fruitless eros, of desire that creates nothing.

The meeting in Purgatorio with Oderisi can also be read as the poet Dante’s commentary on his younger self, when he wrote love poetry that made him famous. Today, that poetry is largely forgotten; it is the Commedia that made Dante immortal. Indeed, though Brunetto Latini was one of the leading public figures of his era, he is mostly remembered today because he turns up in Dante’s immeasurably great poem of God, man, and redemption.

From the circles of Hell and the terraces of Purgatory, we return to the hills of Transylvania, and the discourse of the Hungarian prime minister. Viktor Orbán gave his audience the same wisdom that Dante revealed seven centuries ago. For Dante, this wisdom was not only about private life. Throughout the Commedia, the poet grapples with questions of why political life was such a shambles in medieval Italy. Why had lands and nations that had once been led by giants come to be dominated by aggressive dwarves?

The answer Dante gives is the same one Orbán did at Tusványos:

because men of talent and means had given themselves over to indulging selfish passions, instead of serving God and the greater good.

When you survey contemporary Europe, you see a continent with far more peace and prosperity than Dante and his contemporaries in the calamitous 14th century knew. But you also see overwhelming mediocrity and self-satisfaction. Europe—both its particular nations and itself as a collective cultural entity—has lost its capacity to strive for greatness. Having ceased to believe in God, country, or family, substituting instead pleasure and personal comfort, Europeans run here and there on a sterile desert plain, accomplishing little or nothing of lasting significance. We don’t even make children anymore.

We don’t have to live this way. In a letter to one of his patrons, Dante Alighieri told the man that the purpose of the Commedia is ‘to remove those living in this life from the state of misery and to lead them to the state of happiness.’ The cure for this sickness of the spirit that is killing Europe is what the Greeks call metanoia, and Scripture calls repentance. That is, we have to assess with unsparing truthfulness where we are, and where we went wrong. Then we have to turn with conviction out of the darkness, towards the light.

Hungarians who are looking for a way through this civilizational crisis should turn for wisdom and inspiration to a medieval poet who also lived through a period of tumultuous change, and who found a way out of the ‘dark wood’ of confusion by rediscovering faith in God, and in the things of eternity. Dante was not a Magyar, but like Magyars, he was European—one of the greatest Europeans who ever lived. He speaks to us today, across a sea of time, soaring above the heads of the bustling crowd of aggressive dwarves, and what his booming voice says is: Return.