The twelve months culminating in the US presidential election on 5 November saw more people vote than in any period in modern history. With the notable exception of the election in my own country, the UK, many of these elections have seen a shift to the right: in Argentina, in the Netherlands, in the cross-EU European Parliament election, in France, and most recently in Austria. German Land-level elections show a similar trend. In India too, the broadly national conservative BJP held on to power for a third term, if this time in coalition. Are there any trends here beyond, perhaps, a purely cyclical one? If conservatives, admittedly of very different kinds, are generally doing well in elections, why does it seem so hard to change the direction of political travel in a fundamental way?

In responding to this perspective, I want to ask three broad questions: First, what are the prospects for the ideas of the right in the democratic marketplace? Second, what are the constraints on achieving electoral success for these ideas? And finally, what do the answers to these questions suggest for world order more broadly?

What Are the Prospects for the Ideas of the Right in the Democratic Marketplace?

Should the right be encouraged or discouraged by the political trends of the last year? The answer to that question depends to a large extent on what you mean by ‘the right’. There is, after all, a big difference between Javier Milei and Marine Le Pen. The ‘right’ is a huge oversimplification in today’s politics. It contains at least two very different strands of thought.

One strand is the political and social aspect of right-wing politics—the politics of culture, of immigration, of the nation state, and of cultural identity. These are now largely the preserve of the right: the left has almost entirely abandoned socially conservative ideas in these areas, buying increasingly instead into cultural diversity, globalism, and the dissolution of the nation state. These latter ideas may be fashionable with establishments across Western countries, but seem to be increasingly unpopular with voters. If any trend is identifiable from most of last year’s election results it is one of the growing popularity of this politics of the nation, and individuals. Such an economy undoubtedly has its problems and unsatisfactory outcomes, but in my view much less so than one in which significant economic power is allowed to fall into the hands of the state and in which economic decisions are taken by politicians.

Here, I am more worried, and I am worried partly because our electorates generally seem deeply unsympathetic to such ideas—not surprisingly because no-one has bothered explaining them for decades—and partly because I am not sure everyone on the right wants them. After all the ‘populist’ parties across Europe generally do not have a particularly free-market approach to economics, and an outfit like the National Rally (RN) in France seems in many ways pretty statist in its economic approach. Even within the Conservative Party in Britain, there is a strong wing that advocates an ‘active state’, government-led industrial policy, and living with a relatively high-tax model of society. This seems to me social democracy, not conservatism, and I cannot bring myself to go along with it.

The reason I cannot support such ideas is that everything we know about modern society is that free markets, economic freedom, and a smaller state produce economic growth in a way that other systems simply do not. That is especially true for advanced economies like ours, which live by invention and experimentation. Our failure collectively to live by these values is one of the major reasons why growth across the West is weakening, and of course, ultimately this will undermine our wealth and our power in the world. Indeed, it already is.

Many on the right seem to think that a socially conservative approach to the nation must go with the kind of statist social democratic economic model that I have described. Indeed, this seems to be the political model of many ‘populist’ parties across Europe and beyond. I fundamentally disagree with this. I do not see a contradiction between on the one hand rebuilding our nations politically and culturally and on the other freeing up our economies to restore growth. Indeed, this seems to me the only mix that can in the long run succeed.

Moreover, it seems to me that there is evidence that the ‘right on culture left on economics’ model has a natural limit. Populist right parties in Europe generally struggle to get beyond a third of the vote and often peak much lower. To get closer to an actual majority there needs to be a broader coalition—and the natural such coalition is, as it always has been, one between social and national conservatives on the one hand and free-market liberals on the other. The national conservatives get social conservatism and a stronger nation state, the free marketeers get economic freedom, and we all get greater wealth and prosperity.

The Brexit referendum is an exemplar of this. It could not have been won without, on the one hand, a coalition of patriots concerned about sovereignty and, on the other, a sufficient number of free-market liberals. In Britain, enough of the latter came on board to win, and they did so because they saw the EU as an irredeemably social democratic, controlling, regulatory organization suspicious of free markets and hostile to wealth creation. This is the coalition that has to be built elsewhere if the right is to get over the line to influence electoral outcomes. It will not be built by shying away from building the case for free market economics.

‘I am cautiously positive about the prospects for the ideas of the right. But success in this area is necessary—it is not sufficient’

Can this be done? I am both positive and negative, encouraged and discouraged, as I look at the political scene. The politics of the nation state is getting stronger, but the economics of the free market is, if anything, getting weaker. Still, the balance sheet is positive overall—because restoring the nation-state-based national democracy must be the priority. Without national democracy, it is very difficult to achieve anything else. National democracies can debate policy, they can make missteps, but their electorates must face the consequences of those missteps and they can correct errors. Sovereignty does matter.

One anecdote makes the point. Listening to a recent UK radio interview on energy policy, I heard a derisive Remainer say to a supporter of Brexit ‘you can’t heat your home with your sovereignty’. But in a way you can. Sovereignty gives a nation the power to change its policies. Britain has the power to change its energy policies to make energy cheaper and more abundant. That is our choice. Without that sovereignty, you are in others’ hands. You can debate, but you cannot do.

So sovereignty—the nation, the cultural identity, and the democratic institutions that give it meaning and weight—is the prior necessary condition for success. I believe there is a trend in this direction and it is why I am cautiously positive about the prospects for the ideas of the right. But success in this area is necessary—it is not sufficient. The case for free markets must be made too. But it is going to be a long struggle. There is a very long way to go even to get back to where we were in the 1980s and 1990s, when there was much wider understanding of the power of freedom and democracy, of economic liberalization, and of free markets to drive prosperity and growth. It is the right that has let this argument go. We must get it back. But a generational struggle is before us.

What Are the Prospects for Translating Our Ideas into Electoral Success?

This positive trend for conservative ideas over the last year has not, in my view, generally been translated into actual electoral success. Some on the right resort to conspiracism as the explanation: the belief that Western democracy is in some sense ‘controlled’ by a Davos-linked globalist cabal. This makes no sense and must be rejected. My view, in fact, is that Western democratic mechanisms are working remarkably well in the circumstances. Every country is, of course, different, but people are not shut out from the process; elections take place pretty freely, ideas are to some extent debated, and results, by and large, are honoured.

The reasons to be concerned are rather different. There are trends that will make it harder for the ideas of the right to get electoral purchase unless they are confronted and weakened. Here I want to focus on just two of the most important. The first is the significant, and growing, constraints on free speech in many of our societies. I personally believe that these constraints are themselves a symptom of the growth of political collectivism—that is, the increasing acceptance amongst most political forces that it is reasonable for governments to set political, economic, and social goals for all of society and all individuals within it, and to expect people to go along with these goals in their public lives. The collectivist phenomenon has many causes—the general growth in the size of government, the post-2008 bailouts, the increasing controls on aspects of one’s lifestyle seemingly necessitated by net zero, the impact of pandemic controls, and the fact of mass immigration creating a group-rights mentality and constant negotiation between the groups. We have mostly got used to this, and indeed many of us have forgotten that within living memory society was not like this, and it was not necessary to pay obeisance to state ideologies or public policy as a prerequisite for pursuing one’s own private ends.

The constraints on free speech come as a consequence of these broader developments. Where the government does not impose an ideology or political goals on all of society, debate and dissent is not threatening to the government. But where such ideology is imposed, free speech becomes a problem. Public dissent becomes disruptive. Due obeisance to the gods of diversity becomes necessary to avoid societal friction in a world of mass immigration. Debate about net zero is easily discouraged by stigmatizing as anti-social any unbelievers in the ‘climate emergency’. Governments encourage the belief in misinformation and disinformation and establish various mechanisms to discourage such uncomfortable opinions. The end result of this, of course, is the unwillingness to test ideas in the marketplace, in turn leading to a dysfunctional democracy and the undermining of genuine democratic debate. We are not there yet, but we are some way down the road.

My second area of concern is to do with the ability to produce political change via elections. This is a problem more for the European Union than for the rest of the world. I often make myself unpopular in the UK among opponents of our exit from the EU when I point out that the EU, or perhaps rather the EU system, is not a full democracy. It hits at Europhiles’ self image. But still, it is so. In the EU it is not possible to change everything through national elections because so many issues are handled at the European level. And it is difficult to change things at the EU level either since it is in practice very rarely possible to assemble the kind of cross-European coalitions which can fundamentally change things in Brussels.

This system gives tremendous power to a semi-permanent governing class whose worldview goes into essentially immutable laws that fundamentally shape the EU’s member states. The consequence of this is to set up conflict. If national governments want to reflect the views of their people, then very often this sets up a conflict with Brussels. If they resist that conflict and work within the constraints imposed by Brussels, then not surprisingly we find that voters move from the centre to the challenger, populist, parties, to those who will deal with their concerns, as we have seen in Italy and are seeing in France and Germany.

At the moment the EU system has no way of accommodating this, and it is getting worse, not better. The crisis will come when a critical mass of member states get a majority of voters in favour of significant change. At that point the EU system will have to bend—and it remains to be seen whether the current pressure to shift migration policy will make this happen—or it will break. The choice will be whether to integrate further and create some sort of real democratic legitimacy at EU level or to decentralize once again and give powers back to member states. At the moment, Europeans are just muddling along and setting up what seems to me a genuine political crisis down the line.

What Does This Mean for World Order?

What does this all mean for broader world order? The honest truth is that we cannot know. Most predictions about the world turn out to be wrong. There are simply too many unexpected events and there is always a tendency to extrapolate from current events. Maybe we will see the world coalesce into US-led and China-led blocs, maybe we will not. We can be confident that the world will not develop over the next US presidential term in ways we thought it would. To a very large extent, we have to be ready to respond to events.

But to do that effectively we need, first, to be clear about what is going on in the world, and second, to have the ability to do something about it when it is in our interest. Simply having values which are economically and morally better than those of our opponents—as I believe ours are—does not exempt us from reality. And I worry about what I see.

On the one hand, the West collectively is undoubtedly weaker than thirty years ago. In the US, for the first time ever, powerful currents of opinion are driving the country in the wrong direction, leftwards economically, socially, and culturally. In Europe, as I noted, political and economic developments have driven the EU onto a road that only ends in a dead end, and meanwhile leaves the EU more like the Austro-Hungarian Empire of the twenty-first century, less than the sum of its parts, more a problem than an asset to its friends and allies.

Yet at the same time, our foreign-policy presumptions still seem set by the unipolar moment of the 1990s and by the subsequent series of expeditionary wars—in short, that the West can still make the world bend to our view if we put enough effort in. But reality tells a different story. We are dismantling our energy systems in the name of decarbonization while our geopolitical rivals are doing no such thing. The Ukraine War has exposed the weakness of our industrial base. And many policymakers have a naive and unrealistic view of the power of a supposedly Western-led multilateral system to solve world problems, together with a tendency to see the existential shadow of Munich in every area of friction.

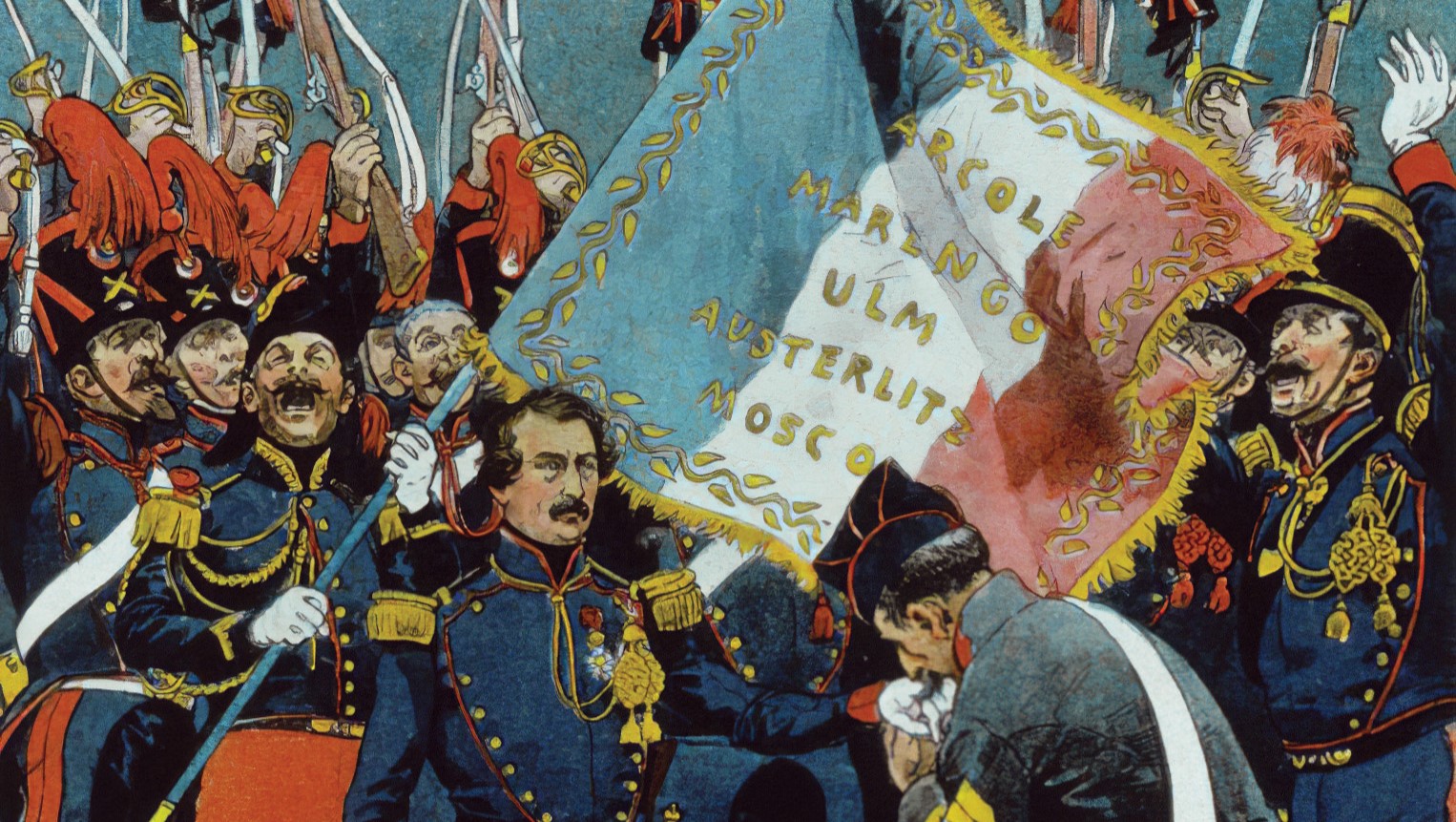

In short, we are showing a mix of weakness and hubris—historically a deadly combination. Since historical analogies are so in fashion, and commentators are so ready to draw them, I cannot help thinking of Napoleon III’s rush to war with Bismarck’s Prussia in 1870. All observers believed France much stronger than Prussia. Yet the Sphinx of the Elysée had been played, and he found his armies defeated and his country dismantled in short order. As Kissinger put it in what is still his masterwork, Diplomacy, Napoleon was ‘unable to assess the relationship of forces and to enlist it in fulfilling his long-term goals…he was unable to establish any order among his multitude of aspirations or any relationship between them and the reality emerging all around him’.1 Who cannot see the parallel with the—in my view highly questionable—belief of so many Western policymakers that the West must be present everywhere, must be involved in solving every problem, and can take on many problems at the same time?

It seems to me, therefore, that the urgent tasks now before Western democracies are to recover our strength, culturally, morally, economically, and politically; to bring our ambitions in line with our real powers; and meanwhile to look in a clear-sighted way at the emerging global reality and avoid needless confrontation and friction if we possibly can.

Maybe these things are not possible, and we will continue to behave as if we were global hegemons while many of our societies are riven by social conflict and economic decline. Certainly, if the left remains in power in leading Western nations, that is all too likely. I believe it is the task of politicians on the right to get real, to win the argument in our own countries for rebuilding our nations, for economic growth, for freedom, for meaningful democracy, and for a foreign policy in line with our real capabilities. We may or may not succeed. But it is our job to make the effort.

This essay is an edited version of a keynote speech delivered by David Frost at the Danube Institute on 17 September 2024.

NOTES

1 Henry Kissinger, Diplomacy (Simon & Schuster, 1994), 119.