Recently, I had the opportunity to visit Hungary’s national gallery in the former palace complex of Buda Castle. The imposing Baroque exterior stood tall as a marvel from another era, and mounted guards in traditional uniforms stood watch at the gates as though the royals themselves had come home. The pieces inside were striking both in their craftsmanship and in the range of styles represented across several centuries. It was well worth the price of admission. Still, the art is not what struck me most that day; neither were the guards or impressive architecture. What stood out to me most was a small café bar in the palace courtyard. There was nothing intrinsically special about it, just gallery-goers and other patrons enjoying a cool drink on a hot summer’s day. Nothing about the small establishment, little more than a counter and backdrop, was out of the ordinary. It was the very fact of it that made it stick out.

I was reminded of a quote by, of all people, German political theorist Friedrich Engels, that I had come across while researching the Revolutions of 1848, which Hungary was part of. As democratic and liberal forces swept Europe, he wrote to extol what he saw as a bourgeois precursor to the eventual rise of the proletariat, ‘Fight on bravely then, gentlemen of capital!…You must draw from our path the relics of the Middle Ages and absolute monarchy…You shall dictate laws, you shall bask in the sun of your own majesty, you shall banquet in the royal halls and woo the king’s daughter.’[1] Of course, Engels then wrote that in spite of these victories, the bourgeois reign would come to its own violent end by the proletariat’s hand. However, it was the violent proletarian revolution that finally came to an end in Hungary with the fall of communism in 1989 amid another wave of liberal revolutions. Still, the fact remains that royal halls across Europe lay dormant, now public displays of grandeur and excess that seem out of place in the modern world. Citizens, not royal subjects, dine in the halls of kings and walk their gardens.

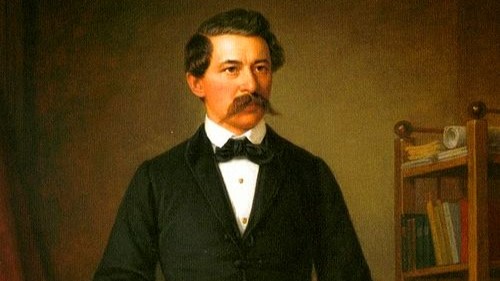

It’s fitting that so many works of art in the gallery, and so much of Hungary’s recent history, looks back to the failed revolution of 1848. I distinctly remember an 1850 painting by Ferenc Ujházy called Bewailing Soldier, depicting a uniformed man mourning by the graves of his fallen comrades, the Hungarian tricolor draped beside him. A monument to the governor-president and first cabinet of revolutionary Hungary adorns the square outside the parliament building.

Hungarians have a long and storied history of opposing tyranny.

For centuries, the medieval Kingdom of Hungary waged war against the advancing Ottoman Empire to the south, until the 1526 Battle of Mohács when Hungary was defeated and partitioned by the Ottomans and Habsburgs. The event is still infamous in Hungary today, with ‘more was lost at the Battle of Mohács’ being a common expression to say that things could be worse. In 1848, Hungarians once more rallied against tyranny, this time from the rule of Habsburg Austria. The April Laws passed that year called for an elected diet, the abolishment of special courts and tax exemptions for nobility, and bound royal power to ministers accountable by law.[2] In the streets, crowds chanted the ‘National Song’, written by Sándor Petőfi: ‘The time is here, now or never! Shall we be slaves or free? This is the question, choose your answer!’[3]

A century later, Hungarians took to the streets again, this time against the Stalinist hand of communist oppression in the wake of World War II. Hungarian students put forward 16 demands calling for non-intervention in Hungary’s affairs, universal secret-ballot elections for a new national assembly, justice for the crimes of the Stalinist regime, and ‘complete recognition of freedom of opinion and of expression, of freedom of the press and of radio’.[4]

Their cries for freedom and dignity were drowned out by gunfire, crushed beneath the treads of Soviet tanks.

But Hungary endured, and in 1989 cast off this last oppressor, finally joining the ranks of liberal democracies it had so long sought after. To mark the victory, Hungarians exhumed and reburied the 1956 revolutionary leader Imre Nagy, holding a funeral ceremony where speakers inveighed against communist oppression and demanded free elections. Some 200,000 Hungarians were in attendance.[5]

This 4th of July, my own country’s independence day, Americans can look with solidarity to the struggles of Hungary and of all democracies against the many faces of tyranny in these last few centuries. In his inaugural address, first U.S. President George Washington looked to the experiment of the new republic as a model for others to follow:

‘The preservation of the sacred fire of liberty and the destiny of the republican model of government are justly considered, perhaps, as deeply, as finally, staked on the experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people.’[6]

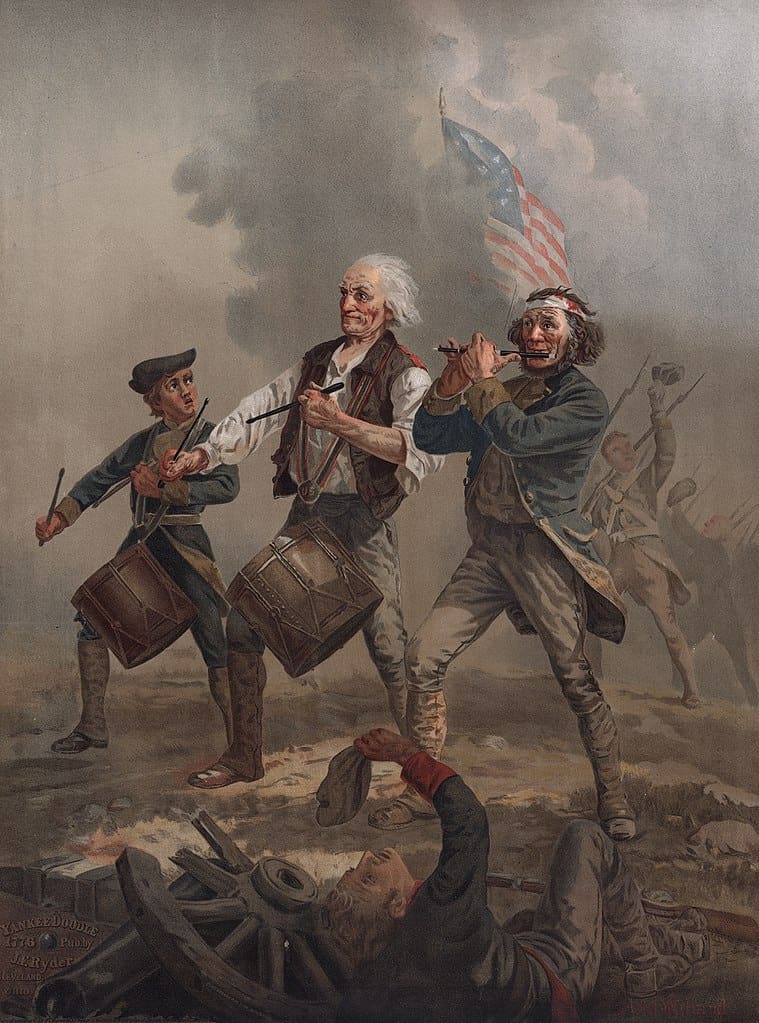

In his later farewell address, he hoped the prudence and prosperity of the new republic would serve as a beacon for all countries, that the ‘auspices of liberty’ might be recommended to ‘the applause, the affection, and adoption of every nation which is yet a stranger to it.’[7] This great quest for freedom gave rise to what is still known as the Spirit of ’76,

a zeal and yearning for liberty and the end of tyranny that could unite mankind to build a better world.

In Hungary, it may be better to call it the Spirit of ’48 or the Spirit of ’56, when the same forces drove the nation to rise against the tide of oppression in search of freedom, even for a moment.

The names of revolutionary heroes are immortalized in Hungary’s history and mythos, much as their faces are immortalized in sculptures and statues around the capital. Their descendants, meanwhile, enjoy the fruits of their efforts: Hungary, like much of Europe and the world, now bears the flame of liberty. Even so, the free world cannot stay idle. In the 21st century, threats on all sides are emerging to challenge the liberal ascendancy arising from the end of the Cold War in the 1990s. We cannot allow past laurels to stand in the way of meeting the challenges of the present. U.S. president Ronald Reagan rightly warned, ‘Freedom is a fragile thing and it’s never more than one generation away from extinction.’[8] The advances of freedom in the world today are monumental, revolutionary in comparison to the vast majority of history. They are the result of courage, vigilance, and readiness to oppose tyranny wherever it appears. The world must be wary of letting that revolutionary spirit fade, of allowing apathy to return the world to a darker time. After all, we are the heirs of revolution, and the world is happier for it.

[1] Theodore S. Hamerow, ‘History and the German Revolution of 1848’, The American Historical Review, Vol. 60, no. 1 (1954), 27–44, https://doi.org/10.2307/1842744, accessed 28 June 2024.

[2] Zsófia Biró, ‘Foundations of the Uncodified Historical Constitution of Hungary’, Studia Iuridica, Volume: 80, No.: , 2019, https://studiaiuridica.pl/resources/html/article/details?id=193403&language=en, accessed 28 June 2024.

[3] Translation by László Körössy (http://laszlokorossy.net/magyar/nemzetidal.html).

[4] Attila J. Ürményházi, ‘The Hungarian Revolution-Uprising of 1956’, American Hungarian Federation, http://www.americanhungarianfederation.org/1956/1956_hungarian_revolution.htm, accessed 28 June 2024.

[5] János M. Rainer, Imre Nagy: A Biography, translated by Hyman H. Legters, London, I.B. Tauris, 2009.

[6] ‘President George Washington’s First Inaugural Speech (1789)’, National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/president-george-washingtons-first-inaugural-speech, accessed 28 June 2024.

[7] ‘Washington’s Farewell Address to the People of the United States’, U.S. Government Publishing Office, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CDOC-106sdoc21/pdf/GPO-CDOC-106sdoc21.pdf, accessed 28 June 2024.

[8] ‘January 5, 1967: Inaugural Address (Public Ceremony)’, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum, https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/january-5-1967-inaugural-address-public-ceremony, accessed 28 June 2024.