The following is a translation of an article written by Dr Ottó Toldi, originally published on the website of the Climate Policy Institute.

Using coal for energy and industry has long been at the centre of the climate and energy transition debate, as it is still the most important source of energy globally for electricity generation, iron, steel, and cement production on the one hand, and the largest source of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions on the other. Therefore, in the EU, most Member States already have so-called coal exit plans to phase out coal and lignite-fired power plants.

However, despite climate and clean energy transition targets, the current energy crisis has forced many countries to increase coal-based power generation, according to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Coal 2022 analysis. The questions are: can we expect a turn in coal use in the short or long term, and, closely related to this, is there any reason for the rise in coal use for energy other than the energy crisis itself?

Energy crises, sanctions, wars, economic slowdowns or not,

global demand for coal skyrocketed in 2022.

The Russia–Ukraine war and the EU/G7 5th sanctions package, which banned Member States from importing Russian coal, have left coal markets unstable, disrupting traditional supply chains and causing wholesale prices to quadruple. Interestingly, despite the economic downturn, demand grew by 1.2 per cent, reaching an all-time high, exceeding 8 billion tonnes/year for the first time. The IEA’s 2021 annual Electricity Market Report said global coal demand could reach a new peak in 2022 or 2023, followed by years of stagnation and then decline. The outbreak of the Russia–Ukraine war in February 2022 and the 5th sanctions package then sharply changed the coal trade situation, price levels, and supply and demand dynamics.

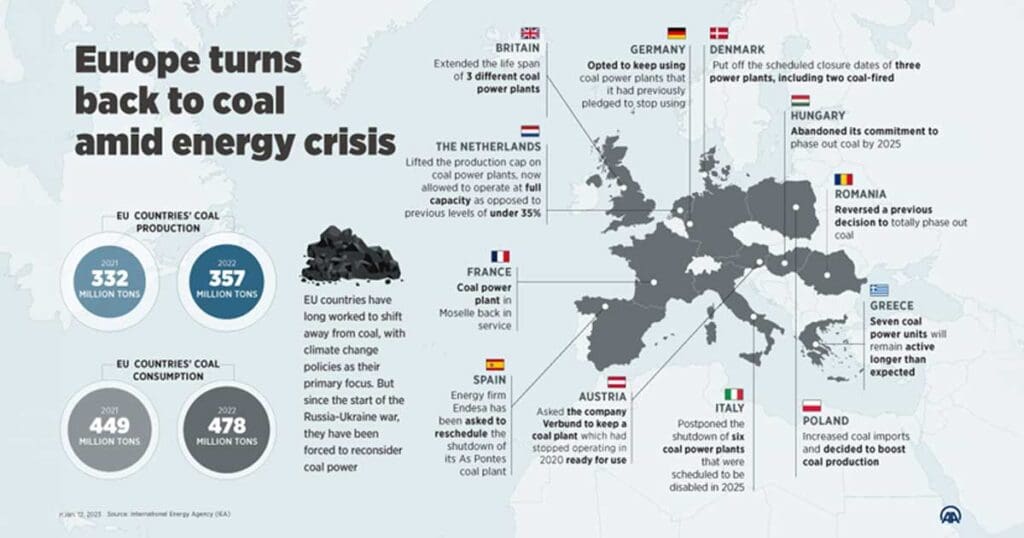

The price of fossil fuels rose significantly in 2022, with natural gas scaling up the most (a six-fold increase between 2021 and autumn 2022). This initiated a wave of divestment from gas, which in practice was mainly reflected in the restarting of coal-fired power plants in reserve or the extension of the operating life of those scheduled for decommissioning. This increased demand for coal naturally led to a rise in prices. EU coal use in electricity generation rose from 449 million tonnes in 2021 to 478 million tonnes in 2022. At the same time, the EU Member States’ own coal production soared from 332 million tonnes in 2021 to 357 million tonnes in the same year, which is a jump of 7.3 per cent.

With higher carbon prices, high carbon quota prices, carbon taxes, and the demand-reducing effect of weakening global economic growth on carbon demand, an equilibrium position with stagnating coal use could have been reached, at least according to the IEA analysis. In their view, the turn in carbon use in the EU will only be temporary, a ‘momentary weakness’. The EU has been made vulnerable by its dependence on Russian pipeline gas supplies, and lower hydropower and nuclear output due to weather conditions. Technical problems at French nuclear plants have put further pressure on the European electricity system. In response, many EU Member States have increased coal-based power generation, but have also accelerated the integration of renewables. Also, where possible, they reduced maintenance times and extended the operating lives of nuclear power plants.

However, the only significant change was in Germany, where the capacity of coal and lignite-fired power plants in operation escalated by 10 gigawatts (GWs) (one and a half times the electricity consumption of Hungary). The IEA predicts that the acceleration in renewable energy capacity expansion will put EU coal use for energy back on a downward trajectory from 2024.

‘The EU would slow down coal use, but China, which accounts for 53 per cent of global coal consumption, has the final say.’

China has an interesting dichotomy in its energy policy. On the one hand, it is investing more in the renewable energy sector than the US and the EU taken together. On the other, it has authorized more coal-fired power plant constructions citing the energy crisis than at any time in the last seven years, despite government promises and targets. In the first half of 2023, 37 GWs of new coal-fired power plants were started, 52s GW were authorized, 41 GWs of new projects were announced, and 8 GWs of previously abandoned projects were renewed.

Thus, the question is, what is driving the newfound wave of coal-fired power plant approvals in China at the dawn of the renewable energy era?

Paradoxically, one of the reasons for the surge in new coal-fired power plant authorizations is precisely climate change. The ongoing drought and last summer’s historic heatwave have led to a huge upsurge in the sale and power consumption of air conditioning apparatus, while at the same time, significant hydro capacity has been taken out of the control system due to the drought. Due to the increased heat and drought, rivers have almost run dry, including even parts of the abundant Yangtze. The heat has also reduced the output of solar and wind power, so China simply had no other choice.

This is compounded by the high price of liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports, which is expected to further slow China’s shift away from coal towards cleaner energy sources in the upcoming years.

While in 2022 and 2023 Q1–Q3, it was the relative rise in the price of alternative energy sources, in the 2023 heating season and the beginning of 2024,

the cold caused the main growth in coal demand.

In 2022, the IEA foreshadowed that the EU would reach the coal consumption ceiling in 2024. In comparison, we see that not only Germany, the UK, the Netherlands, Spain, Greece, Romania, Denmark, Poland, Hungary, and Italy are postponing the closure of their coal and lignite-fired power plants (Figure 1), but also France, which a few days ago announced the temporary re-entry into service of the coal-fired units of the more than 1,500-MW Émile-Huchet power plant, which generate both electricity and heat in a combined cycle. The oldest of these units started operating in 1958, which means that it is neither efficient nor climate-friendly. In Hungary, the originally planned closure of the lignite-fired units of the Mátra power plant in 2025 has been postponed to 2027, when the new gas-fired unit will come on stream, in order to avoid an escalation in electricity imports. Nevertheless, this delay does not really attract our attention anymore, as the Russia–Ukraine war and the sanctions have led to such and similar measures in many countries. The real issue now is rather the winter, which has been colder than expected.

Figure 1. Coal-fired power plants provided 40 per cent of the EU’s electricity generation in 1990, compared to just 13 per cent in 2020. By 2021, around half of Europe’s 324 coal-fired power plants had closed or announced their intention to close before 2030. Today, the share of coal-fired power plants is back above 20 per cent. Coal production is sprouting, and Germany, France, the UK, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, Greece, and Austria have taken steps to extend the lifetime of coal-fired power plants and restart plants that have been closed. In Hungary, the originally planned closure of the lignite-fired units of the Mátra power plant in 2025 has been postponed to 2027, when the new gas-fired unit will come on stream, in order to avoid an escalation in electricity import. SOURCE: International Energy Agency (IEA), 2023

‘The heat market is another segment of the energy sector where the role of solar and wind power is limited’

Here in Europe, we became somewhat lazy in terms of energy use due to climate change. We are used to almost no frost, less heating, hassle-free transport, and everything being always available in the shops. Despite all the forecasts, it is now colder than usual, freezing, and snowing in most of Europe. All the news is about the flooding situation escalating in Western European countries, with thousands of buildings flooded in Britain, France, and Germany, and governments pledging financial assistance to the victims. Meanwhile, in Scandinavia, cold records are being broken. Finland, Sweden, and Norway have recorded temperatures of minus 40 degrees—the lowest in 25 years—and Denmark has also seen a spate of accidents due to snow. But the cold has arrived in Central Europe and Hungary, too, with temperatures dipping below minus 10 degrees Celsius at dawn and even minus 23 degrees in the Bükk Plateau in the first half of January. In this situation, it seems that the EU cannot do without coal-fired power plants, many of which are combined power and electricity generating plants, the latter to meet the needs of the heating sector and district heating companies.

Nevertheless, despite record profits for producers, banks have little interest in further investments in coal mining and coal-based power generation—even if it is not a done deal yet.

In the EU—where the carbon quota trading system and carbon taxes have a significant effect—and in countries where strict air pollution limits have been introduced and are being respected, the turn in coal use is not expected to last. Investment banks will not get involved in risky coal developments if the return on their investment is not guaranteed, and insurance companies will only offer their services at high prices. The end of war conflicts will cause the emergence of new value and trade chains, the energy crisis will end, and greening will continue. However,

there is a chance that energy prices will not return to the lower standards before.

This could lead to the rapidly developing countries with lower liquidity—the BRICS countries in general—becoming excluded of the expensive LNG market, for instance, therefore to a long-term shift back to coal. We can already see examples of this today in countries such as China, India, Vietnam, and Indonesia. Moreover, in these countries, it is not energy market policy but energy policy that decides on major power plant investments. Thus, if the security of cost and supply considerations justify it, they will opt for coal, which seems to remain indispensable in the steel industry (coke is used to adjust the carbon content of steel, which determines its adaptability), in cogeneration, and in the heat market.

Returning to the question in the title, that is, how will global carbon emissions be reduced while coal use continues to increase, the answer can best be summarized as finding alternatives to coal in critical segments: heat generation in the heating sector, carbon regulation and power generation in the steel industry, and power generation in developing countries with large coal reserves but lacking liquidity. In these cases, it is necessary to find cost-effective ways to replace coal with renewables—see biogas, green and decarbonized hydrogen, electrically powered heating systems, etc.—or to be able to use coal and lignite in a climate-friendly way—see clean coal technologies, methanol economy, and carbon capture, usage, and storage (CCUS)—to make decarbonization an alternative not only for rich countries but a truly global option.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.