In his 1966 masterpiece Andrei Rublev, the Soviet filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky meditates on the connection between art and suffering. In the film’s most pivotal scene, the title character, an iconographer, stands shattered in the smoking ruins of a cathedral sacked by barbarian raiders. Most of his work adoring the walls and the iconostasis of the cathedral has been destroyed. He is desolate.

Into this scene appears the ghost of his mentor, Theophanes, who taught him iconography. Theophanes comes to encourage Andrei, and to convey to him the message that suffering will always exist in this mortal life. Andrei’s vocation, says Theophanes, is to keep creating beauty that manifests the reality of the other life, of God’s heaven, where there is no suffering. His holy images will give people hope.

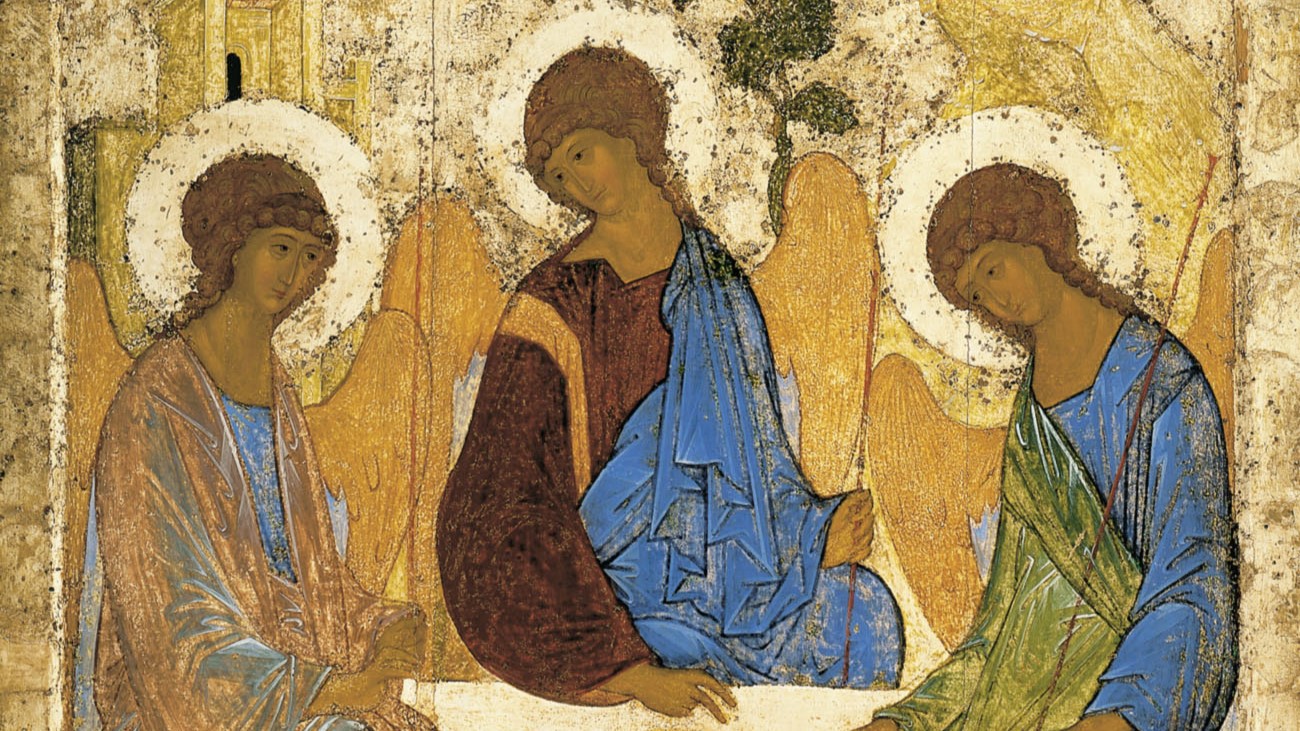

Andrei doesn’t really understand this in the moment, but by the movie’s end, he has recovered faith in his divine mission. In real life, the medieval iconographer Andrei Rublev—considered a saint by Russian Orthodoxy—created icons considered to be the most beautiful ever to come into existence through mortal hands. In the Orthodox understanding, icons exist not for themselves, but as portals into the divine realm. This is generally true about all God-inspired beauty: it exists both to proclaim the glory of the Lord, and to be a doorway through which the All-Holy communicates with us—especially when we are in despair.

This happened to me at an especially painful time in my life, and in the life of the people of my city, and my country, America. It wasn’t in church, but divine beauty is not confined to the precincts of Christian temples.

‘The trauma of 9/11 was a wound that would not heal’

The year was 2002. It was near Christmas. I was living with my then-wife and our two-year-old son in Brooklyn, across New York harbor from lower Manhattan, where the twin towers of the World Trade Center had stood until that horrible day of fire and terror brought to our city by Islamist barbarians. I had stood on the Brooklyn Bridge, watching the south tower fall. When I staggered back home to Brooklyn, my sobbing wife greeted me on our doorstep. She had thought I was dead. In fact, I was covered with white ash and dust, and was in shock.

That autumn was dreadful. For weeks the sour stench of the fire at Ground Zero poisoned the air. I went to the funerals of firefighters killed that day, including eight of them from our neighborhood fire station. The trauma of 9/11 was a wound that would not heal.

And then, in early 2002, the sex abuse scandal in the Catholic Church broke big nationwide. Catholics, as we were in those days, had to face the devastating fact that priests, themselves living icons of God, raped and molested many of our children, and that bishops knew about it, but covered it up. Over and over came the new revelations, landing like artillery fire on the walls of faith and confidence in the Church. I arrived at the second Christmas after 9/11 depressed and confused.

We read in the papers that the Roches were going to perform their annual Christmas concert at Battery Park City, a lower Manhattan neighborhood near Ground Zero. The Roche sisters—Maggie, Terre, and Suzzy—were a trio of singers from the area who had achieved minor fame in the 1970s and 1980s, and who were beloved locally in part because on most years, they would gather on a sidewalk somewhere in Manhattan to perform Christmas carols a cappella. Their harmonies were angelic. The Roches’ Christmas album We Three Kings was a favorite of ours. My wife and I knew we had to be there.

It snowed for hours on the day of the concert. By the time we three set out for Manhattan for the performance, the city was blanketed in white, giving it a magical glow. We came out of the subway and stopped by the gaping hole that was Ground Zero, to pray for the dead. A businessman wearing a trenchcoat in the near distance was making a sound, but I couldn’t tell what it was. My wife, though, had been closer to him, and told me he had been singing the Ave Maria.

Battery Park looked like a picture from a postcard, its trees and benches frosted with sugary snow. As we approached, the Roche sisters were singing Handel’s ‘Hallelujah Chorus’ in three-part harmony. We bought hot chocolate and Christmas cookies, and listened to these gifted women, bundled up in coats and scarves against the snow, sing both sacred and secular songs, proclaiming the blessings of the season. It was hard to think that such beauty manifested blocks away from the site where just over a year ago, thousands of people met their deaths in an act of infamy that called forth a war looming on the horizon.

‘It was hard to think that such beauty manifested blocks away from the site where just over a year ago, thousands of people met their deaths’

As the sisters sang, children ate candy and tossed snowballs at each other. How many of them remembered 9/11? Their mothers and fathers certainly did, and no doubt shared the grace of comfort and even joy that the Roche sisters gave us all through their immaculate harmonies in the snow-covered park.

Then I saw it. Not far from where we stood, an older man stood next to a woman sitting in a wheelchair—his wife, probably. Her face was a frozen mask of sadness and pain. Was she depressed? No: when he brought her a Christmas cookie, she extended her right hand from under her shawl to take it. It shook violently. Parkinson’s disease. That’s why her face was frozen.

I couldn’t take my eyes off the couple, the husband so tender and caring with her, keeping her warm, letting her know with his hands that she is loved. Then the Roches began to sing ‘O Holy Night’, which goes like this:

O holy night

The stars are brightly shining.

This is the night

Of our dear Saviour’s birth.

Long lay the world

In sin and error pining

Until He appeared

And the soul felt its worth.

A thrill of hope!

The weary world rejoices!

For yonder breaks

A new and glorious morn.

Fall on your knees!

O hear the angel voices!

O night divine,

O night when Christ was born.

O night!

O holy night!

O night divine!

As the sisters sang this carol, the old man indeed fell on his knees in the snow, put his face on his wife’s shoulder, and whispered the words to her. I could read his lips. He was singing to his beloved wife, through her suffering.

Everyone in the park that night had lived through the hideous events of 9/11, and the sacking of the cathedral that was our great city. We Catholics were living through an ongoing raid of barbarism carried out by faithless clerics, like the Russians of Tarkovsky’s film, who collaborated with the Tatar Muslim mob that destroyed the cathedral. That poor woman in the wheelchair endured every day the cold touch of death as the disease inexorably snuffed out life in her body. But there was her dear husband, accompanying her with love through her own Gethsemane.

‘It was an inbreaking of light and consolation into this world of darkness and heartbreak’

That night in New York, I too felt the thrill of hope. There in the purity of the snow-frosted park, there was not enough evil in the world to extinguish the good in the hearts of men who love, and who hope in defiance of despair. As the Gospel of John says, ‘The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.’

There would be evil days ahead for me. A decade later, I would lead my wife and our three children to my Louisiana hometown to live, but we found there rejection and brokenness. Our marriage did not survive it. Now I live in Budapest with the son whom I held in my arms that night in Manhattan—he’s now 25—in a kind of exile from the world I once knew, and loved.

Still, the memory of that holy night many years ago stands shining in my memory. It was an inbreaking of light and consolation into this world of darkness and heartbreak. Just as Theophanes told poor Andrei, beauty is a sign that God—born into this world to share our suffering, and to take it onto Himself—has not abandoned us. That at the end of time, as the Book of Revelation tells us, ‘God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away. And he that sat upon the throne said, Behold, I make all things new.’

Read more from the same author: