The Legacy of Post-Communism

As Donald Trump begins his new term as president of the United States and the political right is on the rise across Europe, the example of Hungary, seen as a model by many on the political right, is cast in a new light. The Central European nation of just 10 million, led since 2010 by Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, embarked on a sovereigntist conservative path long before the recent conservative-right wave in the West. 15 years of conservative rule has had far-reaching consequences not only for Hungarian domestic politics, but also for Hungary’s international standing. Considered the ‘front-runner’ and most pro-Western country in its region in the early 1990s, one is often confronted with the question: why Hungary? How is it that under 15 years of conservative government, Hungary has become the European outlier regarding issues ranging from EU integration to relations with Russia?

Taking its title from George Kennan’s famous article on the driving forces of Soviet behaviour, the following series seeks to shed light on some of the key historical developments of recent decades that have strongly influenced not only Prime Minister Orbán’s, but also the Hungarian conservative right’s perceptions of the West and the world. This first of four articles will examine some of the key features of Hungarian domestic politics from the democratic transition in 1990 to 2010, when Fidesz won a two-thirds majority for the first time.

The Disillusionment of Transition

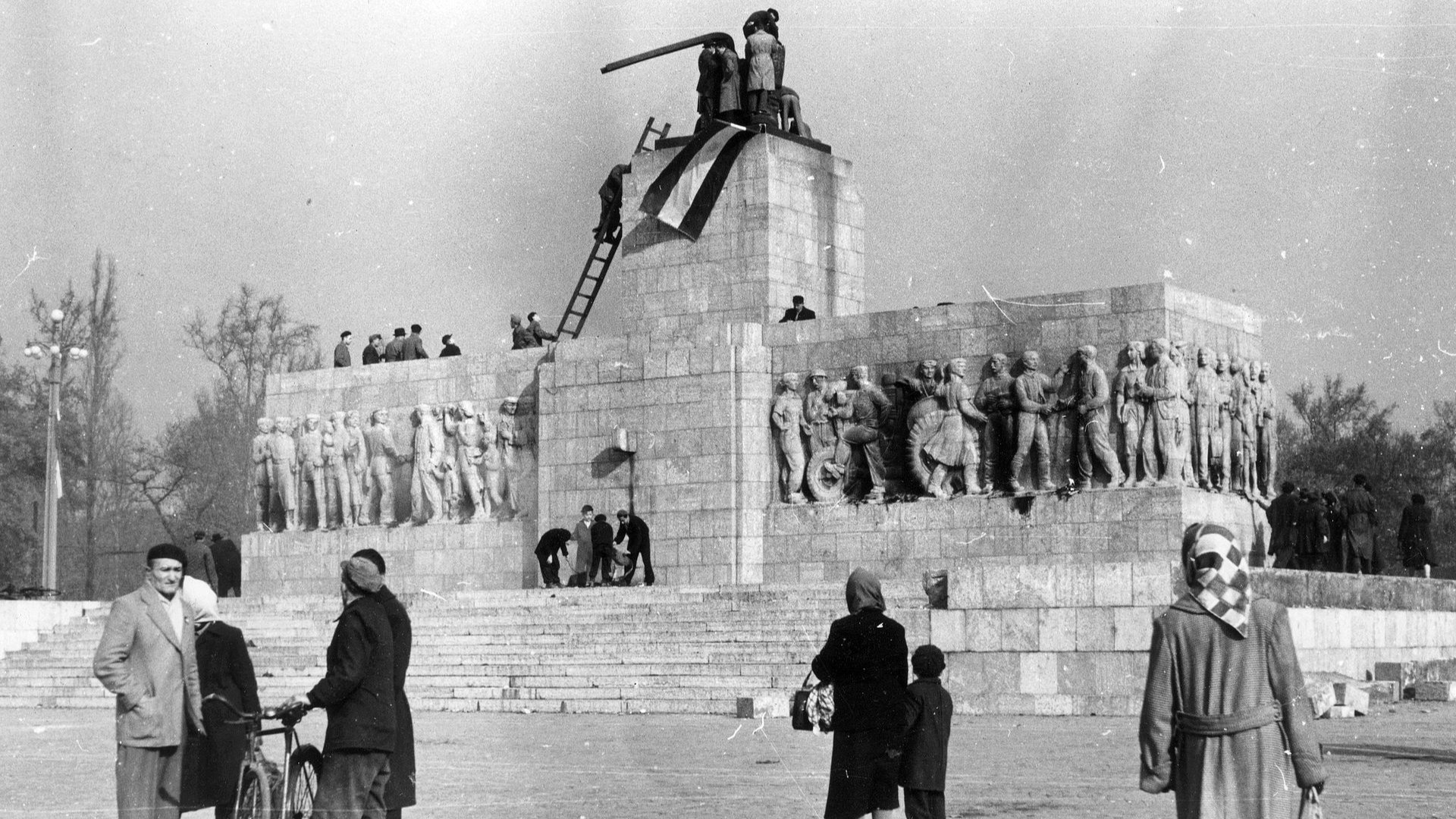

To understand Hungary today, one cannot avoid looking back at the history of the 20th century. Hungarians made the transition from socialism to democracy with the difficult legacy of three major historical milestones of the last century: the Treaty of Trianon in 1920, the Yalta agreements of 1945, and the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. In Trianon, Hungary lost two-thirds of its historical territory and one-fifth of all ethnic Hungarians. The Yalta Pact threw Hungary under the Soviet–Communist imperial bus. The heroic but brutally suppressed 1956 revolution and freedom struggle against the Soviet communist empire cemented Hungary on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain for another three and a half decades. The point here isn’t to judge how unjust these historical events were, but to point out that in all three cases Hungarians felt abandoned by the West. However, this legacy has never made Hungarians hostile to the West, they just wanted to share its successes.

As the Iron Curtain crumbled in the late 1980s, it’s hard to overstate the hopes of Hungarians to ‘catch up’ with Austria, which was seen as a role model for Hungarians. Although support for democracy, the market economy and Euro–Atlantic integration was overwhelming in Hungary during the transition period, ‘goulash communism’ and the top-down orchestrated gradual political transition had their negative effects on Hungarian politics and society. There was no clear break between the old communist dictatorship and the new democracy, that is, between the elites of the ‘old regime’ and the elites of the new democratic system. Albeit a right-wing conservative government came to power in 1990, the informal post-communist networks in the media, the press, the judiciary, academia, and, last but not least, the economy continued to thrive. As a prominent Fidesz politician put it after four years in government in 2002, ‘we were in government, but we weren’t in power.’

‘There was no clear break between the old communist dictatorship and the new democracy’

While the liberal-left parties formally argued against political interference in the media and other parts of civil society, in practice this meant the continued dominance of their narratives in the public sphere. It was so overwhelming that in the mid-1990s there were times when only one national daily newspaper—Magyar Nemzet—leaned to the right, while the majority of the press, public radio, state television and, from the mid-1990s, private radio and television stations adopted a typically liberal-left stance. Strangely enough, Western capitals were not so sensitive about media freedom and balance in Hungary at the time.

One reason for this silence was, of course, Western economic interests. Among the new democracies of Central and Eastern Europe, Hungary went furthest in implementing neo-liberal economic policies in many respects, especially in spontaneous privatization. Compared to the other Visegrád countries, privatization in Hungary was much faster and broader, with obvious drawbacks. The main beneficiaries, apart from old socialist managers and political appointees, were of course Western companies, which not only managed to take over a significant part of the Hungarian economy at a bargain price, but often secured lucrative concessions, especially in public services, or market monopolies at the expense of Hungarian taxpayers and companies. The West was also much less sensitive to corruption when it came to profitable concessions for the construction of highways across the Hungarian plains at exceptionally high prices, which benefited a select few Western companies for many years.

The Mismanagement of the Gyurcsány-Era

Then came eight years of socialist–liberal rule from 2002, with notorious Ferenc Gyurcsány as prime minister from 2004. His famous ‘Lies speech’ to his socialist party after winning the 2006 elections, in which he admitted that ‘we have lied to the Hungarian public morning, noon and night’ about the country’s finances, was met with only a few dishonest waggles from Western politicians. Then, in the autumn of 2006, the most brutal police crackdown in Hungary since 1989 took place, including against peaceful participants in Fidesz’s 1956 commemoration, with dozens seriously injured or unjustly arrested.

But Gyurcsány managed to stay in power for almost two more years, and even then he didn’t step down because of Western pressure over his crackdown on peaceful demonstrators or his disregard for basic democratic principles, but because of the deepening economic crisis. By 2009 Hungary was on an IMF lifeline, government mismanagement and corruption were widespread, and crime was on the rise in deprived rural areas. 20 years of effective rule by the post-communist elites had led the country to a dead end. No wonder Fidesz won its first two-thirds majority in 2010.

The idea that democracy, checks and balances or media freedom were exemplary in Hungary before Fidesz came to power is far from the truth. After 20 years of left–liberal rule, Fidesz’s goal was to stimulate the creation of a much more balanced and pluralistic environment in all segments of society and a country less dependent on any form of foreign influence. In the eyes of ordinary Hungarians, none of the experiences described above called into question the benefits of EU and NATO membership or the conviction that Hungary’s place is in the West. The Hungarian conservative right didn’t become anti-Western, it just became much more sensitive when confronted with Western double standards, hypocrisy or hubris.

Read more from the same author: