‘Politics is not an exact science’, but ‘those who have visions in politics should rather consult a doctor’. The conflicting wisdom of Chancellor Bismarck and his late successor, Chancellor Helmuth Schmidt, highlights the fundamentally complex nature of the study of international politics and the limitations of empirical analysis of politics. Indeed, in addition to material factors such as economic power, military capabilities and geography, visions, perceptions and worldviews continue to play a crucial role in the behaviour of states and the formulation of our overall national goals. Historically and culturally, Hungary belongs to the West; geopolitically and institutionally, its place remains in the European Union and NATO. At the same time, the Western elite, under the spell of progressivism, technocracy and technology, fails to see that it is in fact only one worldview among many, rather than the one and only rational one, while Hungary boldly embraces its value preferences.

The Rule of Perceptions Instead of Rationality

The question of subjective and normative worldviews leads to the eternal dialectic of ‘is’ and ‘should’, which in fact lies at the heart of the fundamental questions of any strategy: what is the geopolitical environment, what is the state of the nation, and what are the objectives we set on the basis of external and internal conditions. During the process of the formation and implementation of a grand strategy, self-reflection is particularly important in order to be able to separate the two: what can be described (‘is’) in our geopolitical environment and in our nation on the basis of empirical investigations, what is expected to emerge from these processes, and what ‘should be’ beneficial for the world or for the nation.

The two concepts above are often conflated in our overly ideological and simplistic public and analytical discourse, thus warning us to be cautious with axiomatic topos such as ‘green policy is good’, ‘diversity should be supported’, ‘Russia is evil’ or ‘America is to blame for everything’. Furthermore, a moral assessment of the behaviour of a phenomenon or a state does not in itself provide a complete answer to the question of what is the right political strategy in response to a challenge. Political action should be guided first and foremost by the consequences of decisions, not by shallow moralism.

Flexibility Instead of Dogmatism

When assessing the likely outcome of competition and conflict between states, it is not enough to assess resources, but geographic proximity, ‘actio radius’, historical past and perceptions of vital national interests should be also taken into consideration. International norms such as sovereign foreign policy or the right to self-determination are important, but who would dare responsibly suggest that the Taiwanese, for example, should feel free to declare independence? The biblical truth ‘all things are lawful for me, but not all things are expedient’ (1 Cor 6,12) applies to geopolitics and helps us to understand how Ukraine was able to heroically resist Russian aggression, but also why the policy of Ukraine and the West up until now, which played on the clear military defeat of Russia, or the push for Ukraine’s membership of NATO, is extremely risky and misguided.

Credible deterrence depends not only on the availability of adequate military force and the willingness to use it if necessary, but also on the correct assessment and establishment of the ‘actio radius’ and red lines of all sorts. From a geopolitical and defence point of view, and in terms of Russian threat perceptions, there is a difference between Finland and the Visegrád countries’ membership of NATO and Ukraine’s possible membership of NATO. Over the past two decades this truth has been confirmed both by the West’s hesitation over Ukraine’s invitation to NATO and by the clear statements of Russian leaders in this regard.

‘In the course of strategic action, dogmatic binary choice patterns that divide the world into good and bad, or the exclusivity of cooperation and confrontation, must be avoided’

Russia is the aggressor in Ukraine, and it would be welcome to see Russian troops withdraw from the occupied territories, but as historians and political analysts, our primary task is not to give a simple answer as to why war broke out, who is to blame, but to explore how we got here by examining also our own—Western—role. And, of course, through ‘the art of the possible’, how can we find a way out of the tragedy of war? Moreover, what does actually winning and losing the war in the case of Ukraine mean? Referring to the famous historian Stephen Kotkin, ‘Ukraine may win the war, but lose the peace’—if the social, demographic, economic costs of more years of war are so enormous. Defence of basic principles of the UN charter are important objectives, but let’s face it: the future of the liberal order will ultimately depend more on the future relative power of the West than on the exact realistic outcome of the war in Ukraine. The war in the East is certainly not the only challenge Europe is facing, but it’s on the top of the list.

In the course of strategic action, dogmatic binary choice patterns that divide the world into good and bad, or the exclusivity of cooperation and confrontation, must be avoided. In Hungary’s relations with the European Union, we have both on a daily basis, and this applies to other international relations as well. In many situations, healthy cooperation in a given dimension of power—for example, economic—could be based on a credible alternative or the ability to show strength in another power dimension. Germany’s mistake wasn’t to build up close energy cooperation with Russia over 40 years, but to do so alongside a complete unilateral military reliance on America and an excessive unilateral energy dependence towards Russia. Both have reinforced the worst reflexes against Europe—and, of course, against Ukraine—in the Kremlin’s rulers. Flexibility and creativity are therefore needed in shaping our grand strategy, as reflected for example in the Hungarian case, through the simultaneous build-up of military forces and the economic connectivity strategy.

Connectivity Instead of Ideology

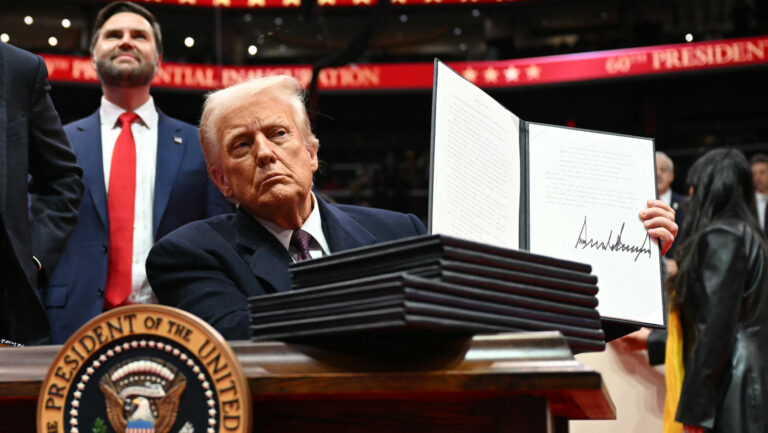

With respect to creativity and the factors that fundamentally affect the viability of the nation, we must also pay attention to the global trends behind geopolitical processes: demographic change, climate change, technological development and the risk emanating from them. The author is convinced that, at the heart of the matter, the conservative side has, on the whole, produced more credible, valid and innovative responses to these systemic global issues in recent decades. It is therefore welcome that, given the trend emerging from recent elections throughout Europe and, of course, the victory of Donald Trump and the Republicans, something has shifted in the West.

If nothing else, the German left-wing government has de facto already admitted that demographic problems cannot be solved by uncontrolled mass immigration—neither on supposed moral nor on economic grounds. Similarly, a responsible climate policy cannot be pursued without a prudent industrial and energy policy. Furthermore, innovation is based on the free market, competition and a work-based economy—values that the technocratic European elite seem all too often to have lose sight of. However, the ‘Entrepreneurial state’ model is not a devil’s play where, due to the delayed historical development, a ‘night-watchman state’ would in fact only entrench intellectual and sometimes market monopolies, as we saw in Hungary in the first 20 years after the collapse of the communist regime.

Only with a strategy based on connectivity will Europe be able to provide a viable response to these global challenges. Not least, an ideology-driven European foreign policy would accelerate the disintegration of the very rules-based multilateral international system it claims to defend so vigorously. Moreover, Europe, to turn Theodore Roosevelt’s enduring wisdom on its head, is usually noisy but ‘carries a small stick’. While for America this is a mistake, it could be fatal for Europe.

‘Economic neutrality would mean a return to normalcy, to the principles and goals that the West stood for in the first two decades after the end of the Cold War’

The Hungarian grand strategy therefore revolves around connectivity or economic neutrality, to use another term. According to the Hungarian government’s assessment, this strategy is not only desirable but also feasible as a member of the European Union and NATO. In fact, economic neutrality would mean a return to normalcy, to the principles and goals that the West stood for in the first two decades after the end of the Cold War. We shall pursuit these objectives without naivety or illusions; surely the World has changed and all great powers are driven more than ever by self-interests. Nevertheless, as Europeans we must still focus on the benefits of an open world economy.

The Hungarian conservative side is also well aware of the truth of a key phrase of the European Parliament elections that we have just left behind, which can be applied to international politics as a whole, ‘War doesn’t determine who is right—only who is left.’ The same applies for international and European politics in general. It has been always the basic thesis of the Hungarian nation that for us is it is never just about the question of who is the world’s leading power, but of how much room for manoeuvre we can gain for ourselves in the shadow of the neighbouring great powers of the moment.

A Polycentric World Order Instead of Western Hegemony

Of course, individual countries not only suffer or benefit from the global trends mentioned above, but they also shape them; usually the more powerful and successful a country is, to the greater extent. The emerging world order, where there will be ‘two suns in the sky’, foreshadows a networked, multidimensional, polycentric international system without a hegemonic power. In this universe, there are also ‘big planets’ (such as India, Brazil, Turkey) that sometimes have more influence in their immediate environment than the two stars. Despite our current disputes in Central Europe, it is in our common interest that the Visegrád cooperation aspire to such a ‘big planet’ role in the long term; as a bridgehead anchored in the West rather than a periphery.

In this multi-factor, dynamically changing international system, the key issue is to continuously improve adaptability and resilience by economic and energy diversification alongside cultivating our essential alliance relationships, strengthening Hungarian and European competitiveness, and doing our part in our common Euro–Atlantic defence efforts. All this can be achieved through a cyclical approach to grand strategy, with regular adjustments as necessary, following Churchill’s guiding principle: ‘However beautiful the strategy, you should occasionally look at the results.’

Related articles: