Earlier this month, the European Court of Justice rejected a petition signed by more than a million Europeans—representing another fifty million—that asked the European Commission to reconsider its position on a proposed and later dismissed minority protection initiative. The Court’s decision appears to be the sad end of an incredible journey. But in order to understand why this feels like a betrayal to Hungarians among dozens of other nations, we need to go back a couple of years to where it all began.

In January 2018, I spent my winter break from university going from door to door, collecting signatures. I remember the temperature was well below freezing point in my small Transylvanian hometown and the streets were covered with a thick blanket of snow as my friend and I made our way from one residential block to another, hoping that they would let us in quickly. We only had a three-hour window every day if we wanted to find as many people at home as we could. And that was the whole point, because we were playing a numbers game that seemed to be stacked against us.

As volunteers, we were part of a giant European grassroots initiative which set out to accomplish the enormous task of collecting over one million signatures back in 2013, to ask the European Commission to protect Europe’s indigenous ethnic minorities. The European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI) is a system devised for the European people to put any issue they want on the table of the commission, save the issue is backed by one million supporters from at least seven member states. We entertained no illusions: of the nearly one hundred initiatives submitted in the past decade,

only four had managed to reach the magical threshold up until that time.

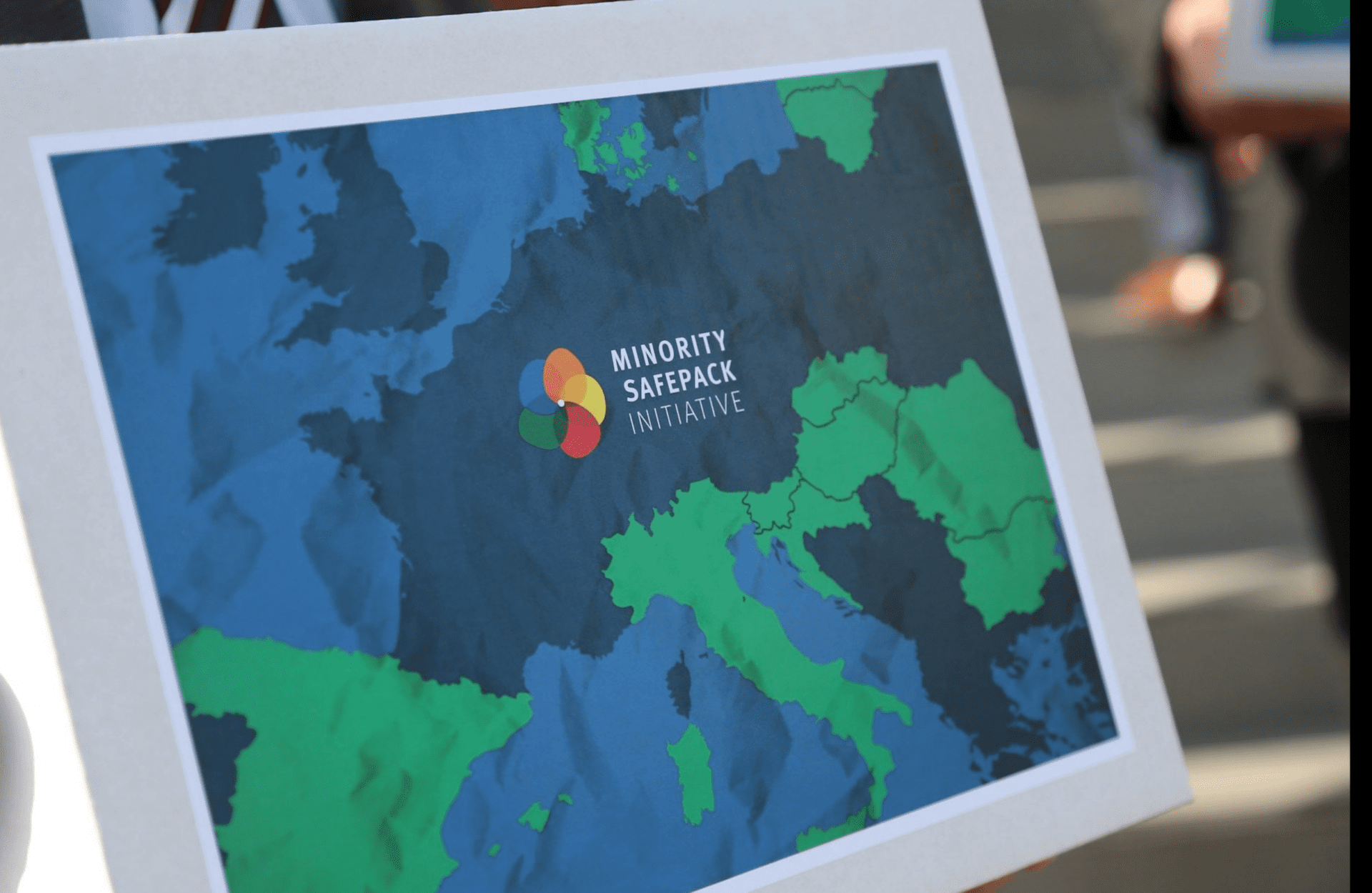

Yet we had to try. The mission that had sounded impossible just a year before was approaching the finish line by early 2018. The originally one-year deadline was extended by a couple of months, and thousands of volunteers were participating in the last push across the continent. And miracles do happen; by April, Minority SafePack (MSP) gathered over 1.3 million signatures (1.1 million submitted after validation).

On January 10th, 2020, we submitted the 1,123,422 statements of support that we collected for #MinoritySafePack during our signature collection campaign. Doing so, we made history: @FUEN_Info became the coordinator of the 5th successful #EuropeanCitizensInitiative in #EU history! pic.twitter.com/2HStBSb6hk

— #MinoritySafePack Initiative (@MSPI_EU) October 24, 2020

While it is true that the Hungarian government was Minority SafePack’s largest supporter, it would be a massive understatement to say that the initiative was about Hungarians. In part, yes, as nearly one in five Hungarians live in their ancestral homelands that are now in Romania, Slovakia, Serbia and Ukraine, and where they face ethnic and linguistic discrimination on a daily basis—albeit to different degrees. The Fidesz government always paid special attention to the problems of these communities, so it was only natural it would also put its weight and resources behind the project. But Minority SafePack wasn’t about the one and a half million diaspora Hungarians. It was about the legal protection of the language rights of fifty million (!) Europeans who belong to indigenous ethnic minority groups. The campaign—organised by FUEN, an international forum of national minorities—gained massive support in dozens of regions such as Catalonia, Bretagne, the Basque Country, Flanders and South Tyrol. It truly proved that Europe was way more diverse than it first appears on the map. And in one way or another, all nine policy recommendations of the initiative asked the same thing from the Commission: to recognise and protect this cultural and linguistic diversity that has always been and will always be quintessentially European.

Now, here’s the catch with any Citizens’ Initiative. Even if a campaign succeeds despite the near-impossible criteria, it only wins the right to be considered by the European Commission. And even though Minority SafePack met all the requirements and even gained the support of the European Parliament, after three years of silence the Commission decided to simply dismiss it. The reason? Minority rights across Europe had gone through ample development since the initiative was submitted, therefore the initiative has become obsolete. End of story.

Not a single point of the policy framework FUEN recommended was put into place.

There was not even a symbolic recognition of the ethnic minority groups and their added value to the continent’s cultural heritage.

The organisers at FUEN immediately took the decision to the European Court of Justice. They could not simply just give up. The campaign was the biggest of its kind in EU history which had required an unbelievable number of resources and countless volunteers to succeed. Besides, FUEN’s putting its last hope in the Court was not simple naivete. It was the Court, after all, that backed Minority SafePack in 2013 when the European Commission initially rejected its proposal. Unfortunately, after twelve months of deliberation, in early November this year the Court dealt the second blow to MSP by agreeing with the Commission’s decision to dismiss it.

Now, exposing the hypocrisy of European institutions regarding ‘diversity’ has become too much of a cliché by now to be worth more than a few lines. It’s so apparent that it’s painful to point out, really. Europe appears to be the global champion of ‘diversity’ but only when it comes to non-European ethnic groups or sexual minorities. Cultural and linguistic minority groups which have been living in Europe for millennia are simply no concern for the Brussels bureaucracy. They are (mostly) white, Christian and straight, after all, and therefore, by definition, cannot be discriminated against. At least according to the liberal dogmas of the 21st century. Not even the word ‘indigenous’ makes a difference, as it has lost meaning in the context of Europe. Yet, it was Europeans who built this continent. Not only the German, French and other great nations, but each and every culture contributed to what it is now—even those without a state of their own.

To be fair, I must also add that the war in Ukraine might have contributed to the Court’s decision. The Commission’s rationale behind dismissing Minority SafePack may have been to avoid increasing the existing tensions between certain member states, such as Hungary’s conflict with Romania and Slovakia (who were the greatest opponents of MSP and even joined the Commission in the initial lawsuit against it). If so, then it’s possible that the Court decided to side with them for the same reason, especially in times when the unity of the bloc is essential as we face external threats. Nonetheless, no one should see the future of fifty million people as a mere strategic question. Linguistic discrimination is a human rights abuse, just like any other. And while billions of euros are invested in the protection and integration of immigrant groups, European minorities are denied even the simplest legal frameworks.

This will likely be the end of the story for MSP. Nine years of hard work and all for nothing, it seems. Truth be told, I was expecting this outcome, but it left a bitter taste in my mouth to hear the news anyway. It made me remember the hundreds of people whose homes I visited in that short week all those years ago. Most were weary after long days of work and wanted nothing more than just to be left alone. And most acted immediately rejective as soon as they heard the word ‘petition’. They don’t give out personal information, they don’t support any parties and they don’t care about politics— we heard over and over again. But after explaining that we were representing a non-partisan European initiative that was meant to protect the language rights of ethnic minorities, the magic happened. The faces softened; the eyes lit up. Many invited us in with warm smiles and almost everyone signed MSP immediately. ‘Young man’, asked a ninety-year-old WWII veteran with a failing voice after proudly presenting his war medals to us, ‘pray tell, do we stand a chance in Brussels?’ I told him the same thing I told everyone else. ‘Frankly, I don’t know much about our chances. But

what I know is that we can’t afford to give up hope.’

Minority SafePack might be over, but the fight isn’t. Even if Europe lets its indigenous ethnic minorities down, the Hungarian government, for one, will never stop being responsible for those beyond its borders. Of course, the lesson has been learned and it’s time to rebrand these efforts if we are to move the heart of Brussels’ bureaucrats. Or, perhaps, we simply need to leave them out entirely and try something different and local, such as improving our bilateral relationships. One thing is certain: there will be other ways as long as there’s a will to find them. In the meantime, we must remember that the future belongs to those who never give up hope.