Max Tegmark’s is one of the most well-known names in contemporary physics and for good reason. The Swedish American scientist and MIT professor is among the most respected in the field of cosmology, the branch of physics that deals with the nature and origin of the universe. With over two hundred publications, Tegmark has made a lasting impact on the current scientific consensus on the origins of matter itself. He developed data analysis tools to be applied to cosmic microwave background experiments, started a new school of interpretation of cosmological quantum mechanics, and established his now-famous mathematical universe hypothesis, revolving around a simple law stating that ‘all structures that exist mathematically exist also physically’. Two things seem apparent when it comes to Tegmark: that he approaches every question from a mathematical point of view and that his observations should not be brushed aside.

Now, as a simple thought experiment for his own amusement, Tegmark calculated the odds of imminent nuclear war as an escalation of the war in Ukraine. We might ask what any of this has to do with his area of expertise, but truth is that global risk analysis is not something that he took up as a hobby last year. Tegmark is in fact the president of the Future of Life Institute, which deals with exactly that. As a non-profit, the FLI works on calculating the catastrophic and existential risks of powerful technologies and offers advice as to how to reduce them. Among the areas studied by the FLI you find climate change, artificial intelligence, biotechnology and—you guessed it—nuclear war. Tegmark is a known opponent of large nuclear arsenals and helped popularise the idea of nuclear winter.

Here's why I think there's now a one-in-six chance of an imminent global #NuclearWar, and why I appreciate @elonmusk and others urging de-escalation, which is IMHO in the national security interest of all nations: https://t.co/HTKLphcOxG pic.twitter.com/kZtTCVhzZu

— Max Tegmark (@tegmark) October 9, 2022

His recent calculations about the chances of an imminent nuclear war were uploaded to his personal blog and from there went viral instantly. His estimate? ‘About the same as losing in Russian roulette: one in six.’ This roughly 17 per cent chance is based on the possible steps of escalations and de-escalations ahead as well as the outcomes of each scenario. There are still many horrible decisions that have to be made along the way for the worst to happen, but the groundwork for that path has already been laid. So, how do we get from Donbas to global annihilation? His reasoning could be a bit complicated to read, so I’ll try to summarise as best I can.

The Rollercoaster of Escalation

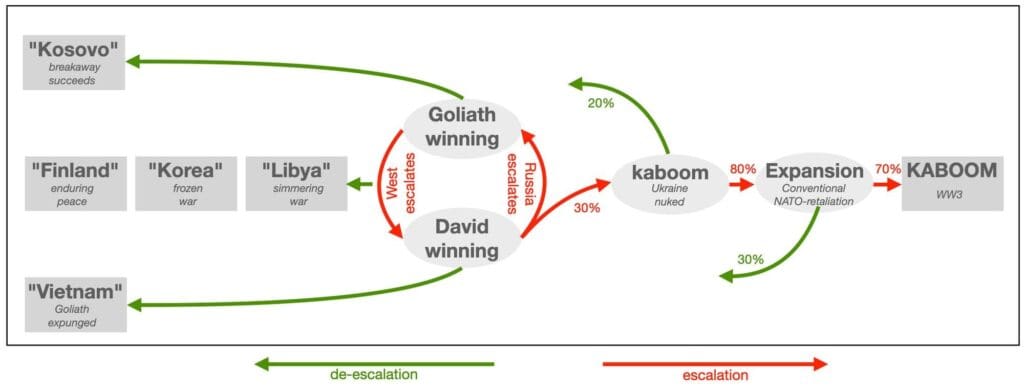

Tegmark’s first basic observation is as follows. ‘We are currently in a vicious circle in the form of a self-perpetuating escalation spiral’: both Russia and the West (including Ukraine) refuse to let the other get any closer to a winning position (called ‘Kosovo’ and ‘Vietnam’ outcomes, referring to scenarios when Eastern Ukraine’s breakaway succeeds, or Russia is expunged respectively). If Putin is highly unlikely (<10 per cent) to accept a ‘Vietnam’ outcome (since it would almost certainly result in the end of his rule one way or another) and the West is also highly unlikely (<10 per cent) to accept ‘Kosovo’ (because if guarantees of not admitting Ukraine into NATO wasn’t an option, allowing permanent annexation isn’t either), then there’s an eighty per cent chance that the war will either progress toward a major escalation or de-escalate into one of the intermediate outcomes: a frozen conflict with different degrees of enduring peace.

In order for Russia to break the current cycle, it would need to escalate qualitatively

In order for de-escalation to happen, both sides should be willing to enter negotiations as soon as possible. But based on the rhetoric we see around us and the ‘near-consensus in mainstream Western media and policy circles against peace negotiations’, the chance of that happening is far less than ideal. On the other hand, in order for Russia to break the current cycle, it would need to escalate qualitatively, since its far less developed economy cannot sustain a prolonged proxy war with the West with simply quantitative, conventional weapons. This means that a meaningful escalation from their side would mean the deployment of nuclear weapons in Ukraine or the lower-case ‘kaboom’ option. Tegmark estimated, that the chances of negotiations resulting in an intermediate outcome against the chances of ‘kaboom’ are two to one at this point.

What happens next largely comes down to the responses taken by the West. Since nukes would have a significant psychological effect on the global populace, there is a sizeable —let us say one-in-five— chance that the United States will be pressured into de-escalation, bringing the war closer to the ‘Kosovo’ outcome. Still, it is way more likely that the US will choose massive retaliation measures using conventional weapons on Russian soil. At this point the ball would be in Moscow’s court to de-escalate and accept some forms of ‘Vietnam’, but chances are they won’t. If Putin views the American retaliation as a declaration of war on Russia and does the same, Tegmark gives a final seventy per cent chance to rapid escalation between the two nuclear superpowers, resulting in the apocalyptic ‘KABOOM’ scenario. One could say that even in case of an all-out Russo-US war, neither party would be so careless as to use their nuclear arsenals against the other, but the Cold War examples paint another picture. As Tegmark notes, ‘[his] 70% estimate factors in that the long history of nuclear near misses has convinced [him] that both the US and Russia are much less competent in de-escalation than in escalation.’

Is This the End Then?

However frightening this sounds, we have to keep in mind that these are just numbers. When calculating the final one-in-six chance for global nuclear war, Tegmark assigned his own estimates to the odds of certain outcomes, based on his subjective observations. They are highly educated guesses, but guesses, nonetheless. And when we start stacking these uncertain numbers across multiple steps, their uncertainty also multiplies. Besides, historical precedence and rational expectations alone are not enough to accurately anticipate any future events. World leaders do not always behave rationally and can also be the subject to assassinations or coups that Tegmark does not seem to have factored in and which could change the entire formula. Similarly, there could be certain interests or technologies that are yet unknown to the opposing parties. Furthermore, we also need to note the human element within both chains of command that might result in refusal of the execution of nuclear exchange and ultimately prevent the worst from happening. Finally, the involvement of any third-party powers, such as China, can easily decrease or increase these chances, depending on its extent and timing relative to the steps outlined.

Nevertheless, if a warning comes from such a distinguished scientist as Max Tegmark, we ought to listen. After all, he did spend half his life trying to reduce the chances of existential threats such as nuclear war. He also accurately predicted during the spring that ‘once loss of occupied territory loomed, [Putin] would annex what he controlled and start talking about nuclear defence of Russia’s new borders’. That worked out to the letter, didn’t it? Therefore, we can trust that the assumptions on which he based his formula are grounded in objective truth instead of a gut feeling.

Avoiding nuclear apocalypse has an 83 per cent chance now

What are the implications of all this? Simple: we need to de-escalate right now. If Tegmark’s formula showed one thing, it’s that the sooner the better. Avoiding nuclear apocalypse has an 83 per cent chance now, but it could drop to 30 per cent quickly if the conflict escalates. Therefore, every country of the West—and not just the US and Ukraine—has the responsibility of doing whatever it can to break the vicious cycle of escalation by peaceful means, regardless of what they seek to achieve in the long term. Our immediate interest is not to doom our planet in a catastrophic nuclear winter, I think everyone can agree on that. However, the United States and most NATO members do not seem sold on the idea of peace, as if this war did only concern Ukraine, and not all of us.

Luckily, some leaders do understand the danger we face. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, for instance, has stressed the need for de-escalation, even at the expense of certain Western geopolitical objectives, countless times. Most recently, at the Euro Summit between the leaders of all 27 EU member states, he called for immediate ceasefire and negotiations with Russia. ‘I asked the leaders of the European Union to debate with the aim of avoiding escalation of the war in mind’, Orbán told reporters afterwards. Hopefully, the number of leaders who agree with him will grow quickly enough.

There is no time to idle and risk pushing Russia into making the next step. The longer we continue sending weapons to Ukraine instead of seeking common ground, the closer we get to ‘kaboom’—and then ‘KABOOM’—every day. Let us avoid that while we can. It is our collective responsibility to keep the mathematics of nuclear winter from becoming physical, and if we fail to do so, history will judge us accordingly.

The expressed in the opinion section are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Hungarian Conservative’s editorial board.