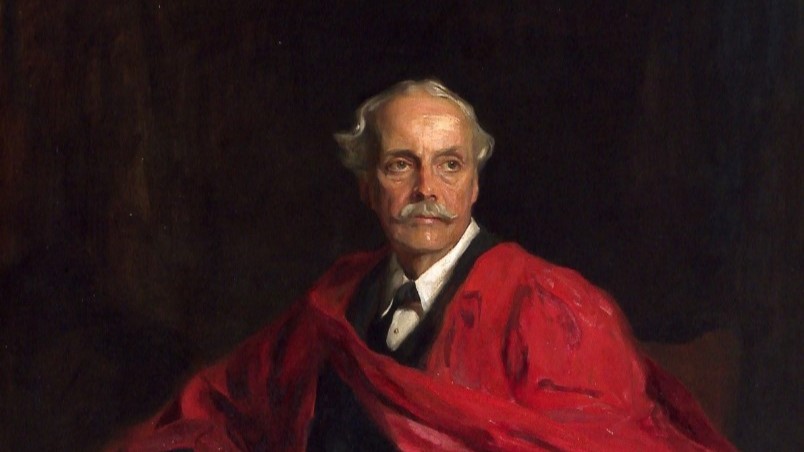

The attack is confident, sustained and completely brazen. A young woman first sprays the painting of Lord Balfour with red paint around his face. She then slashes the canvas with a razor-sharp knife, cutting with bold, decisive strokes. The painting, by the Hungarian artist Philip de László, is quickly and severely damaged, sliced through to its wooden frame, the canvas reduced to flaps in some places. Someone stands behind her, silently filming.

That was on March 8. The vandalism was claimed by Palestine Action, an extremist activist group which specialises in violent attacks on places and objects connected to Zionism or Israel. The group even has an eleven second high quality video of the attack available to download on Dropbox. The young woman does not show her face, which is partly covered by a white medical mask. But she has several identifying characteristics: her height and build can be estimated, her long brown hair is arranged in two neat pig-tails and she is wearing a design Mulberry designer rucksack, costing around £1,000.

‘It feels like it’s now open season on works of art commemorating important figures in Jewish and Zionist history’

Lord Balfour, a modern-minded conservative who was responsible for the 1902 Education Act, was also responsible for the 1917 Balfour Declaration that the government ‘viewed with favour the establishment of Palestine as a national home for the Jewish people’, while emphasising that nothing should be done to prejudice the rights of other communities there. Nine months later nobody has been arrested or charged. Rather, it feels like it’s now open season on works of art commemorating important figures in Jewish and Zionist history.

On November 2, to mark Balfour Day, the anniversary of the Declaration, Palestine Action activists smashed a glass display case and stole two sculptures of Chaim Weizmann from Manchester University. Weizmann, who served as the first president of Israel, had taught in the chemistry department. Once again, the vandalism was filmed and footage shown on social media. A few days later Palestine Action posted a photograph showing what they said was a bust of Weizmann with its head sawn off, under the caption, ‘First bust of Weizmann is dead. Soon his zionist project will be, too!’.

Like ISIS and the Taliban, Palestine Action seeks to reshape the present through destroying the cultural artefacts of the past in acts of savage, intimidatory vandalism. The destruction of Lord Balfour’s painting is an assault, not just on the work of art itself, but an illustrious tradition of beautifully-rendered portraiture, one woven into British and Hungarian cultural history.

Balfour, a graduate of Trinity College, served as prime minister from 1902 to 1905. His portrait was completed in 1914, paid for by subscribers and donated to the College. A highly accomplished work in de László’s characteristic realistic style, it shows him wearing a red Doctor’s gown over a suit, shirt and tie. The two men were close. Balfour was one of de László’s four sponsors when he applied to become a British Subject. Born Fülöp Laub into a poor Jewish family in Budapest in 1869, he lost several of his siblings during their childhood. His outstanding artistic talent won him a place at the National Academy of Arts in Budapest. Laub soon gained fame as a court painter, winning commissions from Emperor Franz Joseph and Queen Victoria. After marrying the British heiress Lucy Guinness, he lived in Budapest and Vienna before moving to London in 1907.

Ennobled in 1912, Laub took the name de László. His descendants, and the cataloguers of his work, were appalled at the attack. That the portrait was targeted is testimony to its enduring power as a work of art. ‘We were utterly shocked by the violent slashing of Balfour’s portrait, so brazenly recorded by the perpetrators,’ said Sandra de László. ‘The girl with her distinctive pigtail was wearing a Mulberry backpack costing some £1,000, suggesting the worst kind of entitlement…This continuing protest by the few against innocent works of art that define the nation’s history can never be justified’.

The day after the slashing, Dame Sally Davies, the Master of Trinity College, issued a short, bland statement: ‘I am shocked by yesterday’s attack in our college on our painting. I condemn this act of vandalism.’ The college was working with the police, she noted, while the community would ‘continue to support each other’.

The university’s lacklustre response has caused growing anger among teaching staff and alumni. Ivan Berkowitz, an American Jewish philanthropist who studied at Trinity, and whose mother survived the Holocaust in Budapest, has withdrawn a £315,000 donation to fund a Rabbinic book project at the college. Instead of properly investigating the vandalism, the University was fixated on ‘elevating wokeness at the expense of the Jewish community,’ Berkowitz told the Jewish Chronicle newspaper. ‘There’s a video of the occurrence and the claim is still that there is not enough evidence’.

It would not seem difficult to track the attacker through the college grounds and the city itself. The university’s own website details how it has an extensive network of CCTV cameras covering the estate. These include Overt Fixed cameras that record images at, for example, reception desks, controllable cameras that can follow subjects or vehicles and ANPR cameras that record vehicles with a time and date stamp. There are more CCTV cameras across and around the historic city centre. The university press office directs enquiries about the attack to Trinity College and to the police. Trinity College has said nothing since Davies’s statement in March. The college also directs questions to Cambridgeshire police. The force said that inquiries continue and there have been no arrests.

A growing number of Cambridge academics are demanding a much firmer response. ‘The failure of both Trinity College and the University of Cambridge to pursue acts of criminal damage in the face of existing evidence about the perpetrators is a testimony to their timidity and preference for appeasement in the face of what is a form of terrorist activity,’ says Professor David Abulafia, a fellow of neighbouring Gonville and Caius College.

In June Palestine activists splashed Cambridge University’s Senate House with red paint, damaging the delicate stonework, under Professor Abulafia’s window. He took some photographs and sent them to the university security office. Again, an investigation is ongoing but no arrests have been made. Meanwhile, sporadic pro-Palestine occupations and encampments on university grounds have continued. The contrast with those arrested after the riots this summer, including those sent to prison for months merely for inflammatory posts on social media, is sharp.

‘The new trinity of sacrosanct beliefs: Palestine/Gaza, man-made climate change and transgender rights are ferociously protected’

The weak reaction to the destruction of the Balfour painting and other acts of vandalism is part of a wider pattern of indulgence, says Professor Matthew Kramer of Churchill College. ‘Ever since the terror attack on October 7, 2023 the university has indulged pro-Hamas and pro-Hezbollah extremists and acquiesced in their demands.’ When Palestine activists occupied part of the university grounds earlier this year, the administration could have obtained an injunction against them and demanded that they leave, says Professor Kramer. Instead it opened discussions with student activists about divesting from certain holdings.

The new trinity of sacrosanct beliefs: Palestine/Gaza, man-made climate change and transgender rights are ferociously protected. Such freedoms would be unlikely to be granted to protestors demanding, for example, limits on immigration or asylum seekers. Cambridge University’s selective approach means that its claims to be upholding freedom of speech are hollow, says Professor Kramer, himself a graduate of Trinity College. ‘Inaction is also a public stand. It communicates to the public that if you undertake criminal action, such as vandalism and the destruction of property, we will be indulgent towards you, provided that you’re acting on the basis of certain positions to which we will accord preferential treatment.’

No cause, it seems, receives more preferential treatment at Cambridge University than Palestine.

Related articles: