In November 2024 Donald Trump once again shocked pollsters by winning the presidency in the United States. This was the second time that he had pulled off such a trick. In 2016, at the height of the political polling analysis fad, polling analyst Nate Silver’s 538 website famously gave Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton a 71.4 per cent chance of winning the election. The fact is that Silver claimed to have this probability down to a single decimal point but when the results came in, it became clear that Trump won by a significant margin. Silver projected 302 electoral college votes for Clinton and only 235 for Trump. The actual result was almost the opposite: 306 electoral college votes for Trump and only 232 for Clinton. Silver himself tried to blame the polling failure on media coverage of his polling outfit, saying that journalists did not sufficiently understand how probabilities work. This was a less radical position than Clinton herself who, no doubt inspired partly by the high probabilities of victory she read on sites like 538, claimed that the election had been stolen from her due to Russian interference in the American election.

Polling Analysis as Political Activism

Silver left 538 in 2023 a few years after the company was bought by Disney and put under the rubric of ABC News. But the polling analytics company continued to publish its forecasts which were heavily followed by political junkies—especially those in the older millennial category who had come of age at the height of the polling analytics fad. After another failed prediction in the 2024 election, 538 was finally shut down at the beginning of March 2025. The closure of 538 has led many to assume that the polling analytics fad that took off in the Obama years when Silver became famous for predicting Democratic Party primaries using demographic data was coming to an end.

During the run-up to the 2008 election, Silver started to publish statistical analyses of the Democratic primaries on the left-wing blog Daily Kos under the pseudonym ‘Poblano’. These posts were highly technical analyses of in-depth polling data which tried to predict the outcome of the primaries based on the demographics at play in each state. Using this type of analysis, Silver was able to determine that Barack Obama was on track to win far more primaries than Hillary Clinton. This was a highly contrarian opinion at the time, as many political analysts thought that 2008 was Clinton’s shot at the presidency.

‘Since then polling analysis has taken a darker though not altogether surprising turn’

Silver’s analysis was widely followed. It got extensive attention when William Kristol noted Silver’s contrarian results in a New York Times column entitled ‘Obama’s Path to Victory’. But it was not so much that Silver was correct that made him famous and allowed him to launch himself as an election forecaster, rather it was the fact that Silver emerged out the blogging culture that surrounded Obama as a political phenomenon. A great deal of the energy behind Obama was from online activists who would utilize Facebook and blogging to support the candidate. While Silver’s analyses were objective and professional, it is hard not to think that he got the attention he did because he was part of this new network of online, left-leaning Democratic Party activists.

From Activism to Revolution in Georgia

Since then polling analysis has taken a darker though not altogether surprising turn. Last year parliamentary elections were held in Georgia. The Georgian Dream party won the election by a considerable margin. The party got nearly 54 per cent of the vote, with the runner up Coalition for Change getting only 11 per cent. Nevertheless, the opposition, led by the then incumbent president, a former French diplomat Salome Zourabichvili, claimed that there was election fraud. Given the enormous victory of Georgian Dream, what led Zourabichvili to make these claims? The clue is in the election polling which has been wildly inaccurate in Georgia for years.

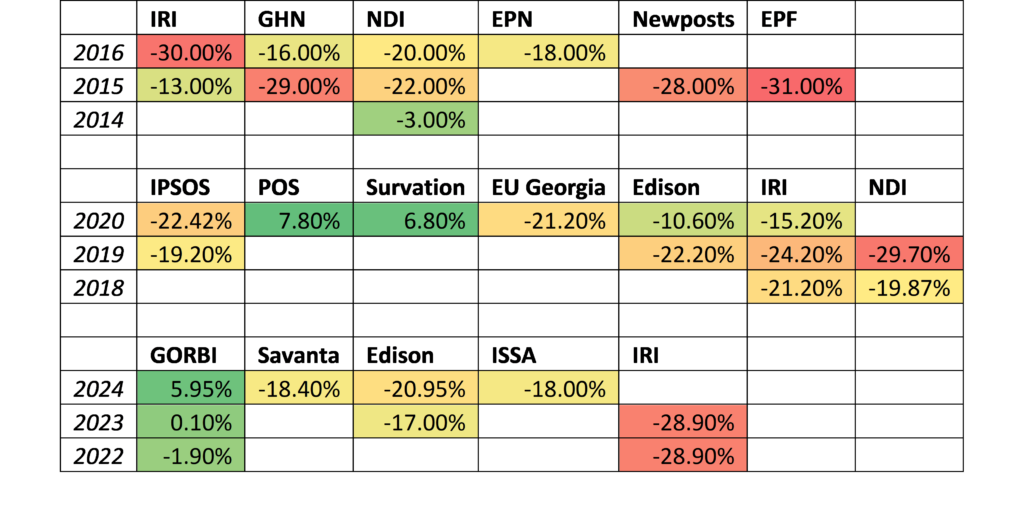

We can see this if we look at the history of Georgian polling compared to election results. The following table shows the averages of each polling companies’ errors when predicting Georgian Dream’s vote share in the elections of 2016, 2020, and 2024.[1] Since polling can change as we move closer to the election, we have broken the errors down into each of the three years in the run-up to the election. The colour coding shows how bad the errors were.

Here we see something remarkable: the polling in Georgian elections has shown extreme bias in every of the past three elections. Apart from a few outliers, if we had trusted any of these polls we would have expected to see radically different results from the actual electoral outcomes. Phrased differently: any opposition party who followed this polling would have had their expectations consistently set far too high relative to the actual election result. The only polling company that even comes close to a prediction within the standard margin of error is GORBI. Interestingly, GORBI is the polling company that is tied to the pro-government television channel Imedi TV. What GORBI shows is that it is possible to forecast Georgian elections within an acceptable margin of error. This raises the question of why the other companies, after having been dramatically wrong year after year, have not tried to update their methodology to get a better estimate of election outcomes.

These inaccurate polls raise the expectations of the opposition parties in Georgia in a manner that is simply not commensurate with the facts. Year after year, Georgian Dream has massively outperformed the polling, but the pollsters never seem to change their methodology. Since the election in 2024 there have been massive, ongoing protests in Georgia. It is impossible to say how much of an impact the inaccurate polling had on the political expectations of those protesting in the streets, but no doubt it a considerable one.

Misleading Polling Comes to Hungary

Western media is currently in a frenzy about an impending electoral upset in Hungary. Péter Magyar is being touted by some as ‘the biggest threat Hungary’s Viktor Orbán has faced in 15 years’. Much of this assessment is based on polling for the upcoming 2026 election which, at the time of writing, show the opposition party Tisza with a lead of around 4 points. Yet when we look at the polling closely, we see that there are major discrepancies which lead one to seriously question its accuracy. Once again, it all comes back to the polling aggregates that are curated by Wikipedia where the polling charts we see in the media originate from. At the time of writing, when we go on the Wikipedia page for the 2026 election in Hungary, we find something that we do not see on other pages: a large section on ‘Pollster Bias’ which tells us the political leanings of various polling agencies in Hungary.

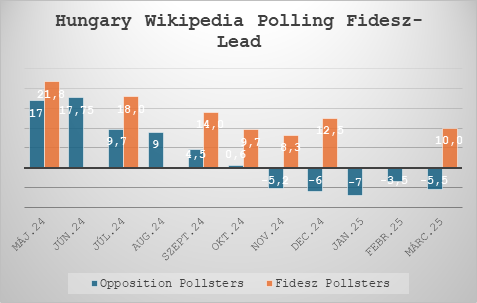

While unusual, this information allows us to undertake a very simple exercise: it allows us to compare polls that are taken by government-leaning pollsters and polls that are taken by opposition-leaning pollsters. Doing so gives us the results shown in the following chart:

Here we see something very interesting: the error between the two types of polls has grown enormously. Until roughly the summer of 2024, the average discrepancy between a government-leaning poll and an opposition-leaning poll was around 6.6 points. While large, this was somewhat within a standard margin of error. Since then, the error has doubled to 13.2 points—certainly outside the margin of error. We can see this in the chart above: if you believe government-leaning polls, Fidesz is ahead by double digits, whereas if you believe opposition-leaning polls, the party is behind by anything up to 7 points.

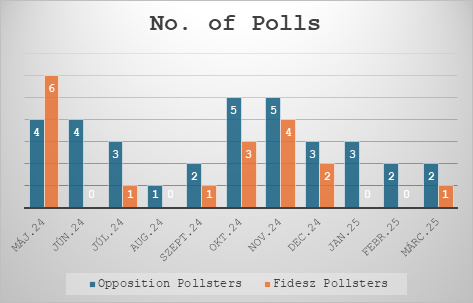

The plot thickens when we look at the relative number of polls by source. The following chart shows this data:

Here we see that the opposition-leaning pollsters are publishing vastly more polls than the government-leaning pollsters. This is a major problem because the polling that the public is seeing is based on averages—moving averages, specifically. When you calculate an average, the averagenumber of samples matters a great deal. For example, if you want to get the average height of a person in Hungary but you take 80 per cent of your sample from the Olympic basketball team, you will vastly overestimate the number. Likewise, if you want to calculate an average of polls but most of the polls are biased to the opposition parties, you will not get a good estimate.

To understand how severe this problem has gotten in Hungary, consider that the opposition Tisza party pulls ahead in the polling aggregates since the beginning of 2025. Yet since January 2025, the polling aggregates contain seven opposition-leaning polls and only one government-leaning poll. The only reason that the opposition appears to have a lead is due to the vast ‘polling inflation’ undertaken by the opposition pollsters. If we take the March 2025 polling, for example, we see that the polling aggregate puts the opposition 4 or more points ahead. But if we weight the government-leaning polls and the opposition-leaning polls equally, we see that Fidesz is over 2 points ahead.

We have seen in the case of the United States that people have too much faith in polling analysts generally. And we have seen in the case of Georgia, bad polling can have negative political consequences. Hopefully, as we move toward the 2026 Hungarian election, more people understand the problems with the polls that are being touted by the media. A little scepticism goes a long way.

[1] The error is simply calculated as the election result minus the average polling for each firm in each listed year. Data is taken from the Wikipedia pages that aggregated the polling data:

2016 Georgian parliamentary election – Wikipedia

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Parliamentary elections were held in Georgia on 8 October 2016 to elect the 150 members of Parliament. The ruling Georgian Dream coalition, led by Prime Minister Giorgi Kvirikashvili, sought a second term in office.

2020 Georgian parliamentary election – Wikipedia

Parliamentary elections were held in Georgia on 31 October and 21 November 2020 to elect the 150 members of Parliament. The ruling Georgian Dream party led by Prime Minister Giorgi Gakharia won re-election for a third term in office, making it the first party in Georgian history to do so.

2024 Georgian parliamentary election – Wikipedia

Turnout 60.20% ( 4.50 pp) Composition of the Georgian Parliament after the election: Coalition for Change: 19 seats Unity – National Movement: 16 seats 2024 Georgian Parliamentary Election Results Parliamentary elections were held in Georgia on 26 October 2024.

Many who are not familiar with polling analysis find it strange that Wikipedia is such an important source for polling analysts. But because it sources volunteers to aggregate individual polls, it is an invaluable tool for analysts. Of course, since Wikipedia is known to have biases, especially political biases, this is highly problematic.

Related articles: