Near the French embassy in Moscow a bus shelter advertisement has appeared which warns the French not to ‘repeat the sins of their ancestors’ who have ‘fought against Russia on the side of Nazis’. The advertisement features Edgar Joseph Alexandre Puaud, a French army officer who led a division in service of the Waffen-SS of Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union.

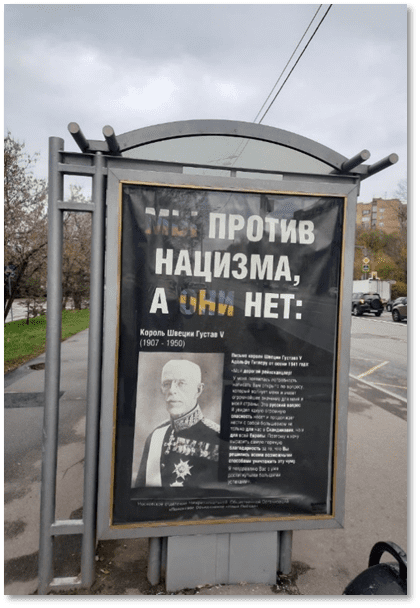

The poster near the French embassy was not the first of its kind in Russia —about a year ago the author of this article saw a similar poster in Moscow near another Western embassy. The picture below shows the ‘advertisement’ at a bus stop right in front of the Swedish embassy which, similarly to the one recalling France’s alleged Nazi ties, accuses Sweden of the same. The poster depicts Gustaf V (King of Sweden from 1907 to 1950) and reads: ‘We (with the colours of the Russian flag) are against Nazism, but they (with the colours of the Swedish flag) are not’. Below the text in capital letters a letter is featured, allegedly written by Gustaf V to Adolf Hitler. In the letter the Nordic monarch addresses the German dictator as ‘My Dear Reichskanzler!’ and expresses his worries about ‘…the Russian question…’ that the monarch later equates with Bolshevism and offers his ‘…sincere thanks to you [i.e., to Hitler] for deciding to strike at this plague…’.

Provocative posters like the ones calling out the French and Swedish embassies are only two of many that were put up in the Russian capital. On 4 July last year, for instance, a billboard appeared in front of the American embassy saying: ‘Welcome to our peaceful country – With compliments of the house, FSB’. Else than the cynical message from the Russian secret service, the Kremlin found other ways too to provoke American embassy employees. The current address of the US embassy is 1 Donetsk People’s Republic Square, which the Russian authorities named in honour of the separatist territory in Eastern Ukraine.

Yet another example of provocative billboards comes from Moscow’s infamous exhibition site, the Patriot Park. For over a year now Russia has been displaying captured NATO technology in the park, where visitors can look at the remains of destroyed Leopard tanks and a multitude of Western infantry fighting vehicles that were sent as military aid to Kyiv. A billboard put up at the entrance of the displayed trophies informed the employees of the US, UK and German embassies that they can attend the open air exhibition without queueing.

Albeit these posters and billboards are addressed to the embassies of Western states, they obviously also send a message to the Russian public. Most of these eyebrow-raising advertisements draw a parallel between the past of some Western countries where some (allegedly) sided with Nazism in the past, and their support for Ukraine today.

According to the Russian propaganda narrative Ukraine is run by Nazis, and the underlaying goal of the ‘special military operation’ is to cleanse Ukraine of Nazis and protect the people of Donbas. Since Ukraine is depicted as a Nazi state, anyone who supports Kyiv is on the side of Nazis—at least according to the Kremlin propagandists. Hence the parallel with Europe’s World War II past.

An important element in refreshing Russians’ collective memory of Europe’s Nazi past was a court decision from May 2023 which

deemed the murder of civilians in the Voronezh Oblast (19421943) genocide,

emphasizing German, Italian and Hungarian responsibility in the matter.

Russia’s so-called evidence of Ukrainian Nazism has been refuted many times. Fabricated images of Ukrainian soldiers appearing to be wearing Nazi slogans on their helmets as well as an incident in a shopping mall with a staircase displaying a LED light swastika were all used by Russian propaganda masters to prove their point. These claims have been debunked as either false or misleading by Western fact-checkers. Nevertheless, the narrative has taken root in Russian public opinio —especially since it is a regularly recurring topic in Putin’s speeches as well (including the one given right before the invasion). Since it is difficult for ordinary Russians to access reliable information about the war in Ukraine, it is no surprise that in opinion polls the public echoes propaganda slogans about Nazis in Ukraine. In October 2023 the Levada Centre asked Russians to name the reasons why Russia started the ‘special military operation’. The second most commonly cited response, named by 14 per cent of Russians, was the need to ‘eradicate Nazism’ as the underlying reason for the outbreak of the conflict started.

Fuelling the Propaganda with Mistaken Decisions

Albeit the Kremlin’s claim of Ukraine being run by Nazis is undeniably false, it is widely recognized by now in the West that Kyiv does play with fire with some radical militant groups that it utilizes in its home defence. These groups have quite apparent links to Nazism. It must be added, however, that it is not only Kyiv’s unwise decision to utilize these fighters but also the West’s recent mistakes and controversial decisions that flame Russian propaganda.

The Azov Brigade is the most famous example of a controversial fascist organization in Ukraine whose example the Kremlin has been using for years to justify its claims.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, the US’ decision this week to lift a ten-year weapon ban on Azov was met with outrage in Moscow. Up until this week Azov was not allowed to receive or use American weapons, but now the US administration changed its policy claiming that it sees no evidence of human right violations on the part of the Brigade. In response, spokesman Dmitry Peskov said that the US is ‘ready to flirt with neo-Nazis’.

Else than the Azov militia, the most well-known example of radicals fighting in Ukraine is that of Denis Kapustin (also known as Denis Nikitin), the leader of the Russian Volunteer Corps (RVC), who led multiple raids into Russia from Ukraine. According to POLITICO, Kapustin is regarded as ‘one of the most influential neo-Nazi activists’ in today’s era. The praise these military formations received in the West for their reckless actions in Belgorod, without recognition of the dangers of their radical ideology, also feeds into Russian propaganda and helps it draw a parallel between the alleged past and present support the West gives to Nazis. The worst incident of all in this battleground of narratives, however, can be attributed to Justin Trudeau’s government. The Canadian parliament’s misguided praise of Yaroslav Hunka, the Ukrainian war veteran who fought with Nazi Germany during World War II, was a godsend in the Kremlin propagandists’ game.

Related articles: