This article was published in Vol. 3 No. 3 of the print edition.

Before and since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Britain has been amongst the most active supporters of Ukraine. Except for the United States, no other country has provided as much military aid, and arguably, no other country including the United States has proved more willing to risk escalation of the conflict up to and including the prospect of a nuclear exchange. This is on the face of it perplexing. Ukraine is of little economic consequence to Britain, as opposed to Russia which is profoundly important. Britain has no strategic interest in Ukraine; nor are there any compelling cultural or historical ties between the two countries.

The Russian invasion was an obvious violation of state sovereignty, which established an emotionally stirring moral narrative that clearly resonated with the British public. The Russian Bear vs plucky Ukraine with plucky Britain behind it. It is this simple view which has animated British policy. Viewed dispassionately and strategically, however, that point of view ignored the fact that the invasion would never have happened if the West had bothered listening to Russian concerns for the past two decades and promised to keep Ukraine out of NATO; that Western moral righteousness over Ukraine plays badly in the rest of the world, which has not seen Western concern exhibited over the violations/invasions of sovereignty in the cases of Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and so on; which has led to a gap that geopolitical intelligence ought to have perceived would result in political shifts that would consolidate a ‘Rest vs the West’ formation, which the likes of China (along with Russia, India, and now Saudi Arabia and Iran) are only too happy to fill.

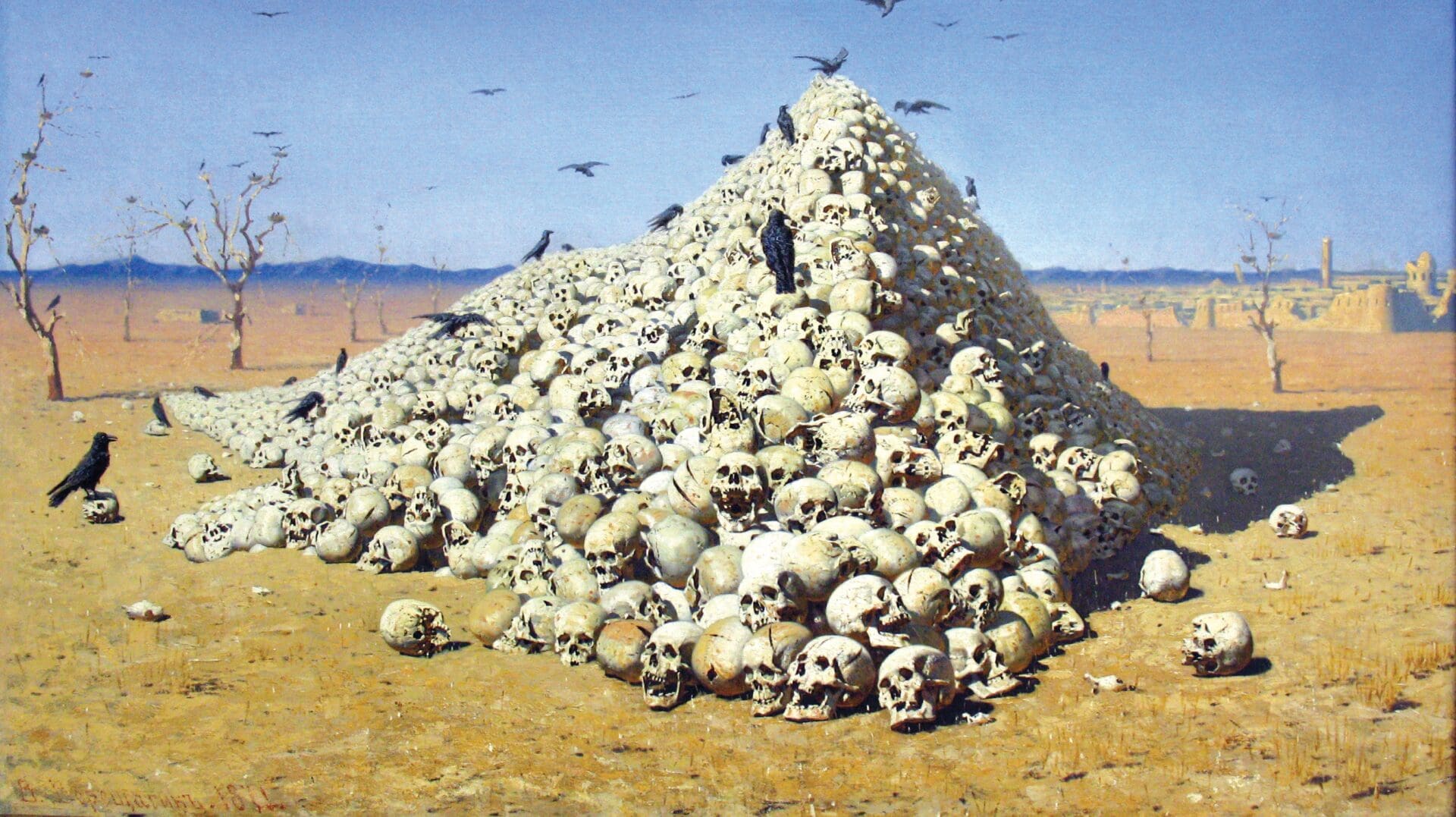

When it comes down to it, this is an unnecessary war which the West, with Britain at the forefront, abetted if not provoked, a war that originated as a civil war in a country of little economic, cultural, or strategic consequence but which we have laboured to metastasize into a global contest that seriously imperils our international standing, economic well-being, and threatens our security. The fact of the matter is that this is the West’s stupidest war with Britain helping to lead the way: unnecessary, unaffordable, and unwinnable.

Geostrategic Catastrophe

Since the invasion of Ukraine, the UK’s efforts to support the regime in Kyiv have exceeded all other countries except the United States. According to a 21 February 2023 House of Commons report, UK military assistance amounted to £2.3 billion. Including economic assistance, the UK’s investment in Ukraine is £3.8 billion. Lethal weaponry provided includes anti-tank missiles—virtually the entire national arsenal of NLAWs and Javelins—artillery, air defence systems, armoured fighting vehicles, anti-structure munitions, and three M270 long-range multiple launch rocket systems. In January 2023, it announced the provision of 14 Challenger II main battle tanks.

Non-lethal aid totals some 200,000 items, including body armour, helmets, night-vision equipment, medical equipment, and winter clothing. In November 2022, the Ministry of Defence confirmed that the first of three retired Sea King search and rescue helicopters had been delivered to Ukraine. The UK has established a long-term training programme known as Operation Interflex for the Ukrainian Armed Forces with the potential to train up to 10,000 new and existing Ukrainian soldiers every 120 days. The Netherlands, Canada, Sweden, Finland, Norway, Denmark, Lithuania, and New Zealand have announced their participation. Australia joined the training programme in January 2023. In February 2023, the government confirmed that training would be expanded to include Ukrainian fast jet pilots and marines.1

Remarks by high-ranking Ukrainian, Russian, and British officers, as well as leaks of classified American military papers, suggest it is very likely also that UK troops are involved in Ukraine in an advisory or training capacity with particularly heavy involvement in Ukrainian influence operations, intelligence, and commando/sabotage raids—notably the Kerch Bridge attack of 13 October 2022 and other clandestine and/or deniable activities.2

Politically, according to multiple reports, it was Prime Minister Boris Johnson who played the key role in convincing President Zelensky not to concede to Russia in the early days of the conflict. Publicly, British ministers—most notably Liz Truss, both as foreign minister and briefly as prime minister—have been strongly supportive of Ukraine and highly vocal about the need to defeat Russia, isolate and strangle it economically, and to punish Vladimir Putin particularly.3 At the sub-ministerial level, some backbenchers have been especially strident, calling for even greater direct involvement of the UK and NATO in the war, as well as downplaying the seriousness of escalation risks.4

‘The Russian invasion was an obvious violation of state sovereignty, which established an emotionally stirring moral narrative that clearly resonated with the British public’

Having inherited this strong position on the war, one wonders whether the current prime minister has any political room for strategic manoeuvre, or whether he is simply committed to going down with the Titanic with what dignity can be managed. The fact of the matter would seem to be that there are no prominent anti-war figures in the British political establishment, including the Opposition. The academic and think-tank world, as well as the major media outlets, are also strongly pro-Ukrainian, frequently overtly anti-Russian, and evince a positive inclination to credulously accept and amplify Ukrainian narratives.

To the extent that it can be judged, UK public support for the war is somewhat more equivocal. A Times poll of March 2022 found that only 45 per cent of young people supported the government’s actions with respect to the war.5 It is probably fair to say, though, that Britons overall are strongly favourable towards Ukraine.6 The narrative which I have noted is one that intrinsically appeals to Britons’ historical self-conception.

All of that is perplexing, though, given: 1) the pre-war importance of UK–Ukraine trade, which at £800 million in imports was a tenth of the value with Russia, which amounted to £10.3 billion in imports—much of that in hard to replace commodities, including fuel;7 2) the strategic irrelevance to Britain of Ukraine, let alone the breakaway Donbass region, which does not cross any trade routes of strategic significance to the UK; and, 3) the fact that Ukraine is not a NATO ally nor democratic but rather more oligarchic than Russia and at least as corrupt.

To a very significant degree Britain has bet its moderately good standing with the Global South and especially China, its economic well-being, the physical condition of its Armed Forces, and ultimately the security of its people on a war that is unnecessary, which the collective West had a more than equal share of provoking, that serves no one in Europe—least of all Ukrainians—and which to judge from the currently faltering Ukrainian counteroffensive we are decisively losing.

None of the above can be justified in terms of national interest. Invoking the defence of the ‘rules-based’, liberal international order is facile and also credibility-damaging. Few outside the West see it that way, or else we would not be seeing the rapid reordering of global alliances that is now occurring. As Mahathir Mohamed, Malaysia’s longest serving prime minister put it, the war is the result of Europe’s ‘love of war and hegemony’.8 Unfortunately, that view is typical in the non-Western world and not exceptional.

Indeed, the war in Ukraine has thrown a spotlight on a scepticism towards the global order that has been growing for some years. A 2015 Chatham House report argued cautiously and hopefully that the foreign and domestic threats to the global status quo then visible were:

‘[S]erious rather than catastrophic. There is little coherence or common interest among the challengers, except for discontent with aspects of the current order, and therefore little coordination. There is no sign of any integrated international opposition movement which might unite the discontented and advocate for an alternative system, leading to the sort of ideological struggle that marked the last century.’9

Now, as epitomized by the February visit of China’s Xi Jinping to Moscow, there is very obviously common interest and increasing coherence among challengers, and much sign of coordination amongst them to redress discontent with the current order.10 It would not be unreasonable to describe this as an accomplished strategic catastrophe.

All Pain, No Gain

The price paid by Britain for its involvement has been high politically, economically, militarily, and strategically, as well as in its continuing and increasing exposure to escalatory risks both sub-nuclear and nuclear. Britain is now on its third prime minister since the outbreak of the war. While its contribution to the political demise of Boris Johnson and Liz Truss was indirect, there is little doubt that foreign policy failings are a part of an image of elite incompetence, dilettantism, and triviality that determines the current public mood.11

The political convenience of the war as a deflection from political scandal, economic misgovernment, and myriad other longstanding domestic challenges has been noted in public discourse.12 For a generation already Britain has fought one war after another, all of them primarily as props in domestic political theatre, most of them based on a ‘strategic’ prospectus no more thought through than ‘something must be done’ whether or not that something was useful, let alone wise.

Economically, the costs have been significantly damaging—an effect that is very likely to be longstanding. Reading Truss’s belligerent Mansion House speech from April 2022 is now quite painful: ‘There can be no more free passes. We are showing this with the Russia–Ukraine conflict—Russia’s pass has been rescinded. We are hitting them with every element of economic policy.’13

The fact of the matter is that Britain is now verging on recession, according to the government, while Russia, according to the IMF is likely to be headed back into growth.14 The war has thrown into especially stark relief the tragic and decades-long inadequacies of British energy and industrial policies. Huge energy price rises have hit consumers, small businesses, and energy-intense manufacturers hard. The cost-of-living ‘crisis’ shows every sign of becoming a permanent feature. According to the Office of National Statistics, the cost of food and non-alcoholic drinks in the year up to March 2023 rose 19.2 per cent, the highest rate in forty-five years, and ‘largely in response’ to the Ukraine War.15

Ultimately, for Britain to have tried—and failed—to weaponize the global financial system against Russia may be the most impactful. The fortunes of the City of London, having squandered its reputation as a safe and rule-bound place for the world to conduct its financial affairs, are also uncertain.

Outside of the United States, the ructions caused by the hastening de-dollarization of international trade (a development which would have seemed absurd a year ago), the global economic decentring of the Atlantic overall, are likely to be felt worst in Britain. In his 24 February 2022 speech, President Putin ruminated on the possible countermeasures to Russia and its ability to respond to them:

‘Indeed, today they [the West] have great financial, scientific, technological, and military capabilities. We are aware of this and objectively assess the threats constantly being addressed to us in the economic sphere, as well as our ability to resist this impudent and permanent blackmail. I repeat, we evaluate them without illusions, extremely realistically.’16

A year later, the only reasonable conclusion of his extremely realistic assessment is that it proved to be highly accurate. The aforementioned Moscow summit meeting of Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin marks the accomplishment of a Eurasian compact and a functional division of the world into two parts: the West on one side, or more precisely the increasingly financially tenuous dollar area plus the politically tenuous EU and its satellites, and Russia and China on the other, with each making their own proposals to the rest of the world.

It is far from obvious that the West has the better offer. The BRICS, none of which have joined sanctions against Russia, now account for as much as 80 per cent of global heavy industry and a massive chunk of vital commodities, including, as recent events have highlighted, food and fertilizer, and a gigantic slice of the world’s actual savings. In March 2023, it was announced that the BRICS had overtaken the G7 in their share of world GDP by Purchasing Power Parity.17

The West, meanwhile, is in serious economic peril—much of the reason for that stemming from over-financialization and unsustainable debt. As of 2022, America’s debt-GDP ratio had already reached 129 per cent on a ballistic trajectory that is set conservatively to reach 225 per cent by 2050. By comparison, the historic high in 1946, bearing all the costs of the Second World War, was 106 per cent.18 The truth, though, is that the numbers will never rise to that height because the system will collapse first. As it was put to me by a former senior banker and diplomat, ‘it can’t happen as investors won’t accept it. This sort of thing normally ends in hyperinflation, conflict, and loss of empire!’19

The problem is not simply American, because no Western economies are in much better structural order, and several are in significantly worse. In terms of economic financialization, further debt issuance, and consumption, the collective West has reached the end of the line. For Europe, stark rises in energy and freight costs, combined with recession reducing domestic demand for industrial products, on top of an already higher cost base than other advanced economies, make energy-intensive firms unprofitable.20

In short, the homeland of the industrial revolution is being de-industrialized at a rapid pace. The currently unfolding economic downturn, a long overdue recurrence of the 2008 Financial Crisis, is combining with a progressive de-dollarization of global trade turbocharged by sanctions on Russia.

Who is on track to economic ruin here? Who has ‘contained’ whom? Militarily, the UK armed forces, which were already in a profound state of disorder and demoralization after twenty years of fruitless expeditionary campaigning in support of the American War on Terror, have been further denuded. Arsenals have been drained while at the same time military structural, organizational, training and other deficiencies which were already latent have been placed under a spotlight.21

The quality of army leadership, moreover, is extremely questionable. The British Army currently could not put a single battle-ready division in the field, and its ability to perform numerous other smaller commitments is also dubious. Its equipment is poor and insufficient in quantity but at the same time highly expensive. For a country ranked fifth or sixth in the world in terms of defence expenditure this is astonishing.

‘The fact of the matter is that this is the West’s stupidest war with Britain helping to lead the way: unnecessary, unaffordable, and unwinnable’

Aside from the effect on war stocks, the Russo-Ukraine War did not cause these problems. The complacent state of rotten ineptitude in the command of the British Army has been remarked upon by other observers for some time already.22 What the Ukraine War has done is throw a powerful spotlight on the matter and accelerate the growth of pre-existing problems. The fact is that while Russia has demonstrated that it can conduct large-scale modern war, as has Ukraine—albeit as the proxy of NATO with its full backing, for now—Britain does not have the same potential. The very obviousness of this imperils conventional deterrence overall. One might well interpret the recent Argentine statements about the Falklands, as well as the recent public American official musings about the quality of Britain’s army, as reflections of it.23

Strategically, the situation is extremely dire. In the long view, the rise of China is something of a historical inevitability—its recent century-plus period of relative economic and military weakness was bound to be corrected. The strength of the alignment, however, of Russia with China, which increasingly includes the BRICS generally—to which are being added significant new players, notably Saudi Arabia and Iran, was not inevitable. This is a thing which one might well conclude that British policy has actively sought to create, so adroitly has it been accomplished, were it not for the obviously self-harming quality of it.

Demographically and economically sclerotic, politically tumultuous, and for that matter socially and culturally ever more desiccated, Europe is for the foreseeable future severed from access to an unparalleled reservoir of natural resources. An increasing majority of global manufacturing, the largest fraction of the world’s youthful scientific and business innovators, and the biggest chunk of its vital natural commodities are now located in a bloc with which we are in effect already at war.24

For Britain, as an offshoot of Europe, it is perilous being caught between one crumbling empire and another. British strategists often invoke Halford Mackinder, the great British geostrategist of the early twentieth century. In Democratic Ideals and Reality, written just after the First World War, he warned:

‘Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; who rules the World-Island commands the world.’25

These lines are, fairly obviously, intended to serve an argument in which Russia is seen as the natural geographic ‘pivot’ of history and that denying it control of the territory and resources of Ukraine, therefore, is strategically vital to maintaining Western predominance.

The irony is that the West’s efforts to prevent the emergence of the dreaded World-Island have backfired spectacularly. One obvious reason for this we might reasonably surmise: Russian (and Chinese) strategists are perfectly capable of reading Western texts which clearly state its plans to forestall the rise of any potential challengers to its primacy, and act accordingly.26

Another reason, though, is that whatever its merits with respect to the world of the early twentieth century, Mackinder’s theories require serious adaptation to be of much use in the twenty-first century. At the time Democratic Ideals and Reality was written, China was a bit player on the global scene—populous, vast, and historically intriguing but at the same time economically and militarily prostrate and politically practically moribund. Clearly, that is now no longer the case. It would do, therefore, to consider more seriously the very last line of Mackinder’s thesis:

‘Were the Chinese, for instance, organized by the Japanese, to overthrow the Russian Empire and conquer its territory, they might constitute the yellow peril to the world’s freedom just because they would add an oceanic frontage to the resources of the great continent, an advantage as yet denied to the Russian tenant of the pivot region.’27

Leave aside the remark about the role of the Japanese in this scenario, a point which serves to illustrate the difficulties from the perspective of a century ago of imagining China acting as an ambitious global player in its own right. In other words, while fighting to the last Ukrainian to contain the supposed re-emergence of Russia as a great power, the West has propelled into being more or less exactly the thing Mackinder warned against. And no direct Chinese conquest of territory was required to obtain this prize.

The Tide Is Out

The situation is dire in the long and medium term. Simply, the global order is being reshaped faster than anyone might have imagined before the war occurred. It is akin to that described by the famous investor Warren Buffet with his adage about the revelatory quality of economic downturns: ‘You don’t find out who’s been swimming naked until the tide goes out.’28 The tide is out and amongst a crowd of now obviously naked swimmers is Britain.

Meanwhile, though, the short term is also exceedingly precarious. Notably, there is the matter of potential escalation, risks of which, for obvious reasons, have centred on nuclear weapons. At the time of writing (in early May 2023), a Ukrainian drone attack on the Kremlin, extremely unconvincingly denied by Kyiv, has heightened such fears.29 Less frequently observed is that Russia possesses several potentially very powerful non-nuclear opportunities for escalation. These include probably cyber attack and certainly anti-satellite attack, either of which (but especially the latter) could be very damaging. Likewise, it might attack NATO AISR assets which up until March 2023, with the attack on an unmanned American drone over the Black Sea, it had abjured.30

Another possibility, however, and one to which Britain is very vulnerable, is an attack on undersea communications and gas infrastructure.31 One of the surprising revelations in Seymour Hersh’s account of the American demolition of the Russo-German Nordstream 2 gas pipeline is that the Royal Navy does not seem to have been involved in it.32 That action, though, has clearly demonstrated the possibility that the infrastructure of nominally third-party participants in the conflict is in play. It would be surprising if Moscow did not consider a wide range of currently largely unguarded infrastructure to be a legitimate potential target.

To all of this must be added one final element which is the availability of weapons. Since February 2022, however, the West has injected tens of thousands of unaccountable high-grade military weapons, including man-portable air defence and anti-tank missiles, into Ukraine and from which Europe is ‘separated’ by one of the world’s most-permeable-to-smuggling borders. The current most optimistic guess is that such weapons have not made their way onto European black markets in large numbers—yet.33

The Blind Leading the Deaf

The past year has seen the birth of a class of punditry that is possessed, or so it says, of insight into the Russian military ‘playbook’ and Kremlin thinking generally, of an apprehension of the Russian public mood, and an understanding of the content of Russian arsenals, plus the capabilities of its arms industry and the durability of its economy. From it we have learned that Russian strategy has failed, the Kremlin fears a coup d’état and/or Putin is ailing physically and mentally, that the population is restive and latently anti-war, that it is running out of modern weapons and cobbling together primitive ones out of stolen washing machines, that its economy is on the ropes, and the country is diplomatically all but isolated.

The connection of any of this to reality is dubious. The outpourings of UK defence intelligence have been particularly credulity-challenging and credibility-straining. It would seem fundamentally to be acting as the strategic communications platform of the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence, whose narratives it repeats and amplifies, more than anything else.

Although it is anecdotal, I think that the following story might illuminate what has been happening. At an event involving the Euro-Atlantic defence in September 2022, I was advised by a senior American official that they did not have good insight into the ground reality in Ukraine. This was because, he surmised, the Ukrainians had taken from the debacle of the Afghanistan withdrawal the lesson that the Biden administration was mercurial and might ‘throw them under the bus’, i.e., turn on them, if politically convenient. It was the American view, however, that there was a good deal more trust between the Ukrainians and the British and so that gave them some visibility on things.

This conversation was followed minutes later by one with a British defence official who told me that they did not have a great deal of confidence in their knowledge of what was happening because the Ukrainians considered Britain ultimately to be a very junior partner to the Americans and felt little need therefore to open up to them. For example, when a British delegation admonished a senior Ukrainian intelligence figure over the torturing and executing of Russian POWs, revealed in a widely-shared March 2022 video, they were brusquely advised to ‘mind their own f***ing business’.34 He added, though, that they reckoned the Ukrainians were being up front with the Americans and so at least in that way the major Western allies had some effective and clear local knowledge.

Over dinner that evening, a colleague who had recently resigned from a high-level NATO role to pursue academia, mentioned that for the first four months of the war there was intense frustration in Brussels because the Ukrainians were telling them nothing about ammunition expenditure, casualties, remaining stockpiles and so on. As he put it, they said ‘hey, we’re giving you all this stuff and you’re telling us nothing’.

I considered these discussions in the light of one other, which was with a very highly regarded American war reporter, an author of numerous long-form analyses published in prominent newspapers and magazines. His thesis is that the Ukraine War is a civil war, which has been metastasized beyond all reason into a global civilizational contest. He explained at length the many unanswered and important questions about the politics of the war, notably the real power dynamics behind the Zelensky government. The curious thing, however, is that none of these things have featured in his published articles on the war so far.

Whether this was a result of self-censorship or the active exclusion of awkward narratives in Western media is another good question. The fact of the matter, though, is that with few exceptions coverage of the war in the West has been dismally partial, partisan, often just historically and strategically ignorant.

What is a reasonable, objective, moderately well-informed person to make of this? I am such a person and have concluded that none of the people who are supposed to know what is going on do, while some of those who do have an idea are prevented or discouraged from speaking out in a way that would contradict the narrative. This is really a dangerous situation because it is a recipe for defeat. Ancient Chinese general and military strategist Sun Tzu said, know yourself and know your enemy, that is the route to victory. It is fine to lie to your enemy. It is stupid to lie to yourself.

As for our knowledge of Russia, the reality, in my view, is simply that whatever was its original intent Russia has settled into an attrition strategy vis-à-vis the West that is very likely to succeed. NATO’s options are few and, moreover, inadequate (for example, Britain’s 14 Challenger MBTs) or so pregnant with the potential for escalation as to be politically unacceptable.

Russia’s military performance has been adequate and, more importantly, is on a strengthening trajectory both in scale and competence. Its military casualties have been grossly exaggerated. The opposite is the case with Ukrainian forces. Russia is not painfully diplomatically isolated and its economy, most surprisingly its industrial potential, is rather more durable than was supposed a year ago. Russian public support for the war does not seem to be faltering at all.

Rather a lot has been made of the supposed salutary effect of the war on NATO unity, which to my mind is a line of reasoning that simply beggars belief. The fractures in the Alliance, many of which preceded the war, are no less wide than they were and in some cases much, much wider. The American demolition of the Russo-German Nordstream 2 pipeline is without doubt the single-most most astonishing act of intra-alliance politics in the history of NATO.

Indeed, there is a historical parallel to an event in which one power attacks a lesser one with which is not at war, in fact is nominally an ally, in order to forestall it from adopting a position of neutrality on a conflict. It is that described by Thucydides in his history of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta known as the ‘Melian Dialogue’.35 In that case, the island of Melos wishing not to join in the war was bluntly warned that it had no choice but to join the Athenian empire. ‘The strong do as they will, while the weak do as they must’, claimed the Athenians—no further moral justification of power was offered in the fifth century BC, nor it would seem is any necessary in the twenty-first century.

As for Britain, for reasons that defy easy explanation, its leaders have required no arm-twisting but instead have joined in what is arguably the stupidest war in its history—a history that is rich in stupid wars—with enthusiasm.

NOTES

1 Claire Mills, ‘Military Assistance to Ukraine since the Russian Invasion’, Research Briefing, House of Commons Library (30 March 2023), https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9477/CBP-9477.pdf.

2 See Paul Adams and George Wright, ‘Ukraine War: Leak Shows Western Special Forces on the Ground’, BBC (11 April 2023), www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-65245065; and Harry Adams, ‘Royal Marines Took Part in “High Risk” Missions in Ukraine, Ex-commando Chief Reveals’, ForcesNet (13 December 2022), www.forces.net/services/royal-marines/royal-marines-deployed-discreet-operations-ukraine-high-political-and.

3 Peter Dickinson, ‘Why Ukraine Loves Boris’, Atlantic Council (4 July 2022), www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/why-ukraine-loves-boris/.

4 See Tobias Ellwood, ‘NATO Has Been “Too Timid” to Take on Vladimir Putin’, Times Radio (26 February 2023), www.youtube.com/watch?v=gvkeZYRBn_c.

5 Larisa Brown, ‘Only 45% of Young People Supported the Government’s Actions with Respect to the War’, The Times (22 March 2023), www.thetimes.co.uk/article/only-45-of-young-britons-support-uk-role-in-ukraine-poll-suggests-wnl7skdd6.

6 See Gideon Skinner et al., ‘Public Continues to Support Britain’s Role in Ukraine Conflict’, IPSOS (31 October 2022), www.ipsos.com/en-uk/public-continues-support-britains-role-ukraine-conflict.

7 See ‘What Did the UK Trade with Ukraine in 2021?’, Office of National Statistics (30 March 2022), www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/balanceofpayments/articles/whatdidtheuktradewithukrainein2021/2022-03-30; and ‘UK Trade with Russia: 2021’, Office of National Statistics (22 March 2022), www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/balanceofpayments/articles/uktradewithrussia/2021.

8 See Ben Norton, ‘Ukraine Conflict “Caused by Europeans’ Love of War, Hegemony”, Says Malaysia’s Ex Leader’, Geopolitical Economy (25 February 2023), https://geopoliticaleconomy.com/2023/02/25/ukraine-europe-love-war-hegemony-malaysia/.

9 ‘Challenges to the Rules-Based International Order’, Royal Institute of International Affairs, The London Conference (2015), www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/London%20Conference%202015%20-%20Background%20Papers.pdf.

10 Austin Ramzy et al., ‘Chinese Visit to Moscow Showcases Deepening Ties with Russia’, The Wall Street Journal (19 February 2023), www.wsj. com/articles/chinese-visit-to-moscow-showcases-deepening-ties-with-russia-feba99d2?mod=article_inline.

11 See Lucy Lee and Penny Young, ‘A Disengaged Britain? Political Interest and Participation over 30 Years’, in A. Park et al., eds, British Social Attitudes: The 30th Report (London: NatCen Social Research, 2013); and more recently Matthew Goodwin, Values, Voice, and Virtue: The New British Politics (London: Penguin, 2023).

12 For instance by Toby Helm, ‘From Partygate to Putin’s War: Boris Johnson Rides on a Rare Wave of Unity’, The Guardian (26 February 2022), www.theguardian.com/world/2022/feb/26/partygate-putin- war-boris-johnson-ukraine-crisis-prime-minister.

13 Liz Truss, ‘The Return of Geopolitics: Foreign Secretary’s Mansion House Speech at the Lord Mayor’s 2022 Easter Banquet’, Mansion House, London (27 April 2022), www.gov.uk/government/speeches/foreign-secretarys-mansion-house-speech- at-the-lord-mayors-easter-banquet-the-return-of-geopolitics.

14 International Monetary Fund, ‘A Rocky Recovery’, IMF.org (11 April 2023), www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2023/04/11/world-economic-outlook-april-2023?cid=bl-com-spring2023flagships-WEOEA2023001.

15 Office of National Statistics, Insights on Cost of Living (3 May 2023), www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/articles/costofliving/ latestinsights.

16 See ‘Full Text: Putin’s Declaration of War on Ukraine’, The Spectator (24 February 2022), www.spectator.co.uk/article/full-text-putin-s-declaration-of-war-on-ukraine/.

17 Chris Devonshire-Ellis, ‘The BRICS Has Overtaken the G7 in Global GDP’, Silk Road Briefing (27 March 2023), www.silkroadbriefing.com/news/2023/03/27/the-brics-has-overtaken-the-g7-in-global-gdp/.

18 Megan Henney, ‘US National Debt on Pace to Be 225% of GDP by 2050, Penn Wharton Says’, Fox Business (19 December 2022), www.foxbusiness. com/economy/us-national-debt-pace-gdp-2050-penn-wharton-says.

19 Correspondence by author with Alastair Walton (1 February 2023). See also Ray Dalio, Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed or Fail (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2021).

20 ‘Europe Outlook 2023: The Threats to Europe’s Industrial Competitiveness’, Economist Intelligence Unit (2022), https://pages.eiu.com/rs/753-RIQ-438/images/europe-outlook-2023.pdf?mkt_tok=NzUzLVJJUS00MzgAAAGKZZVbu-5pxQg89C2zU0XW7mp6W6OzOO7yQ2G0fUcdNG-DV_mL134UwLLMs9_NsEalXnNaZhykvAfyOZMXX-MuE-ZCw55DB6GJqwSOqSdHlf-0z6fQw.

21 See, for example, Danielle Sheridan et al., ‘France “Concerned” about State of Britain’s Armed Forces’, The Telegraph (14 February 2023), www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2023/02/14/france-concerned-state-britains-armed-forces/.

22 See Jim Storr, Something Rotten: Land Command in the 21st Century (Havant: Howgate, 2022); and, an even more blistering indictment by Simon Akam, The Changing of the Guard: The British Army Since 9/11 (London: Scribe, 2021).

23 See ‘Argentina to Renew Push for Sovereignty over Falkland Islands’, Al Jazeera (2 March 2023), www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/3/2/argentina-to-renew-push-for-sovereignty-over-falkland-islands.

24 The total value of Russian natural resources is estimated at $75 trillion followed by the USA at $45 trillion, ‘Top 10 Countries with Most Natural Resources in the World’, Basic Planet (21 March 2023), www.basicplanet.com/top-10-countries-natural-resources-world/.

25 Halford Mackinder, Democratic Ideals and Reality (New York: H. Holt & Co.), 106.

26 In particular, the argument of Zbigniew Brzezin-ski, based on Mackinder, as expressed in The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives (New York: Basic Books, 1997).

27 Mackinder, Democratic Ideals and Reality, 193.

28 Warren Buffet Archive (25 April 1994), https://buffett.cnbc.com/video/1994/04/25/buffett-you-dont-find-out-whos-been-swimming-naked-until-the-tide-goes-out.html.

29 ‘Zelensky Denies Ukraine Sent Drones to Hit Putin, Kremlin’, Bloomberg News (3 May 2023), www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-05-03/russia-says-it-downed-drone-attack-on-putin-s-kremlin- residence?leadSource=uverify%20wall.

30 ‘US Decries Russian Collision with American Drone over Black Sea’, Al Jazeera (14 March 2023), www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/3/14/white-house-slams-russia-jet-collision-with-us-drone-in-black-sea.

31 Sebastian Seibt, ‘Threat Looms of Russian Attack on Undersea Cables to Shut down West’s Internet’, France24 (23 March 2022), www.france24.com/en/europe/20220323-threat-looms-of-russian-attack-on-undersea-cables-to-shut-down-west-s-internet.

32 Seymour Hersh, ‘How America Took out the Nord Stream Pipeline’, Substack (8 February 2023), https://seymourhersh.substack.com/p/how-america-took-out-the-nord-stream.

33 Charles Davis, ‘Weapons in Ukraine Aren’t Flooding Europe’s Black Markets, But That Could Change’, Business Insider (27 October 2022), www.businessinsider.com/no-sign-of-mass-arms-trafficking-from-ukraine-authorities-say-2022-10?r=US&IR=T.

34 Thomas Eydoux, ‘Does This Video Show Ukrainian Soldiers Shooting at Russian Prisoners of War?’, France 24 (31 March 2022), https://observers.france24.com/en/europe/20220331-ukraine-russia-video-prisoners-of-war.

35 Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War (London: Penguin, 1974), 167.