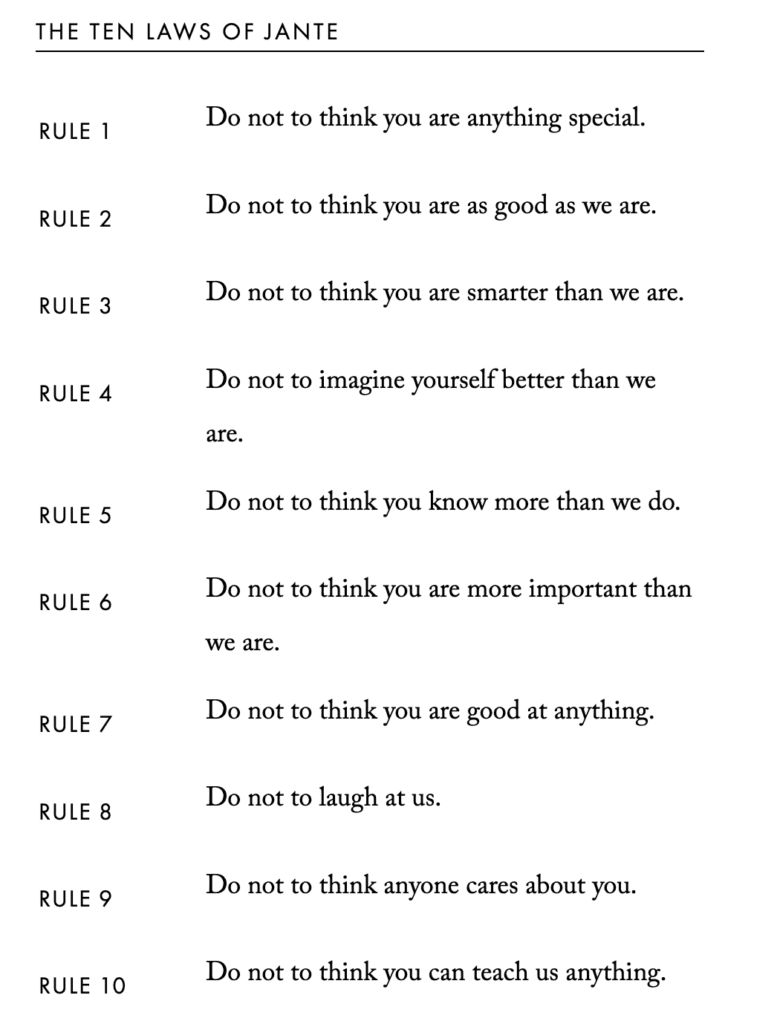

To most of the world as in Scandinavia itself, the relationship between the words ‘Scandinavian” and ‘contrarian” could effectively be construed as oxymoronic. The region’s status as a Kultur-cum-Sprachbund, where universal adherence to self-effacing social norms is heavily emphasized in abet of the dominant equalitarian ethos, seems to be the least fertile ground one could possibly imagine for contrarian values. Indeed, Janteloven (or the Law of Jante, a codification of Scandinavian cultural values first devised by author Aksel Sandemose) appears explicitly opposed to the very possibility of any actions in the public square that might rock the proverbial longboat, so to speak. So what on earth could possibly be responsible for the recent controversy in multiple Scandinavian countries over iconoclastic blasphemy and the individual freedom of expression?

First, a brief timeline. During June this year in Sweden, an Iraqi Christian refugee of Assyrian descent by the name of Salwan Momika burned a copy of the Qur’an outside Sweden’s central mosque in Stockholm. The response to this—both in Scandinavian countries beyond Sweden itself, as well as in the Muslim world thousands of miles away—was entirely predictable. What was less predictable, however, was the indescribable audacity of Momika himself, who reacted to the mass unrest provoked by his actions across the entire planet by proceeding forthrightly to do the exact same thing again. It should be noted that, in doing so, Momika explicitly presented himself as fighting on behalf of free speech. The book he burned, he alleges, was a threat to that cause.

In doing so, Salwan Momika managed to skyrocket into the stratosphere of controversy, reaching a level of notoriety more typically frequented by warmongering politicians, terrorists, and mass murderers than it is by book-burners or TikTok trolls. Momika has been banned from all social media platforms, and his Facebook account, where he had posted videos and long essays about his political views and the Assyrian Christian cause in Iraq, is long-since gone. Momika has been condemned by virtually everyone you ask; thus far, condemnations have come from the Swedish government, from Iraqi Christian representatives, and from both Sunni and Shi’ite Islamic leaders, to name but a few. Judging from the references to his ‘controversial background’ and ‘complex past’ commonly seen in Western media coverage of Momika, it appears that support will not be forthcoming.

But Salwan Momika himself is arguably the least interesting part of this story. The events that unfolded as a result of his actions in Stockholm include a full-scale attack on the Swedish embassy in Iraq eerily reminiscent of the assault on Benghazi in 2012, the expulsion of Swedish diplomats from Iraq by order of the Iraqi prime minister, and—if it wasn’t obvious by now—a catastrophic collapse in diplomatic relations not only between Sweden and Iraq, but arguably also between Sweden and the Muslim world at large. What started out as a deliberately provocative demonstration by a single individual in Stockholm has now escalated into a full-scale culture war in which the social and political values of the Nordic countries are set against those of the nearly 2 billion people represented by the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). The OIC, having demanded that Sweden “take action” to prevent such acts in the future, has in effect dictated terms to Sweden that require this sovereign country to reimagine the most fundamental aspects of its political and legal constitution—namely, the freedoms of thought and expression.

And for better or worse,

it appears that Scandinavia at large is poised to capitulate to these demands.

According to a recent BBC report, both Sweden and Denmark are in the process of re/examining or even revising their respective legal systems so as to illegalise acts such as those of Salwan Momika. Whatever may come of this prospective ‘ban’ on blasphemy, if indeed it materializes at all, it is worth reminding ourselves that this is in no way designed to protect the sensibilities of Christians, or Jews, or Buddhists, or Zoroastrians, or believers of any other stripe and colour.

The legal investigations underway now in Denmark and Sweden are a direct response to the supremely adverse reaction shown by Muslims in Scandinavia (that is, largely communities of recent immigration extraction) as well as those in the Muslim world writ large toward blasphemous exhibitionism. The goal of such politico-legal countermeasures is to inoculate their respective governments against the allegation of being Islamophobic—something that carries serious weight in the Islamic world. In other words, it appears that concerns relating to diplomacy here triumph over any genuine offense the Swedish government might take to the act of blasphemy itself.

But does the neorealist strategy that Sweden and Denmark appear to be flirting with align closely with the history and heritage of the Scandinavian countries? The short answer is: no. In actuality, Momika’s sacrilege is far from novel in the context of Scandinavian culture. Ever since the Protestant reformation, the burning of religious texts by rival factions has been a familiar, albeit egregiously iconoclastic, act of disrespect in the countries of Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland (the Counts War in which monasteries were looted with impunity being a well-documented instance of this). Centuries before that, the burning of books and desecration of rune inscriptions was a relatively commonplace event during the height of the competition for converts between Christianity and Old Norse Paganism (or Ásatrú, as it is sometimes also called), the destruction of the Temple of Uppsala by Christians being a primary example.

Blasphemy, or at least open expressions of disrespect toward other faiths, was formerly somewhat of a Scandinavian pastime.

Even in modern times, the relatively popular status of convicted murderer, arsonist, and musician Varg Vikernes, a black metal star who admitted to burning down some of Norway’s oldest and most fantastic wooden churches, speaks volumes about Scandinavian sentiment toward supposedly sacreligious actions. His music project Burzum released an album, Aske (Norwegian for ‘Ashes’) which displayed the cover art of a church he allegedly burned down.

Such brazen feats are so extreme that they put American gangster rappers to shame. Varg Vikernes was arrested, convicted, and served his time—yet his arson of Christian places of worship itself has not induced anything approximating the reaction exhibited by Muslims across the globe toward the burning of a single Qur’an in Stockholm.

So what exactly does it mean for Sweden and Denmark (or perhaps even Scandinavia as a whole) to pivot away from Scandinavia’s historical lenience toward differences of faith and opinion, in favour of an as-yet undefined system that might sacrifice individual freedoms for the sake of social and geopolitical harmony?

First of all, it means that Scandinavia is still Scandinavia, and that Janteloven is still in effect. Westerners from the Anglosphere, failing to understand the nuances of Scandinavian history and culture, tend to overestimate the role of individualism in Scandinavian culture, past and present. The shock and horror exhibited by the American right toward this apparent act of capitulation by Sweden and Denmark is fundamentally rooted in a quintessentially American understanding of what an ‘individual’ is, and what rights he or she has. The collective decision by Sweden and Denmark to rethink their very constitutional laws so as to guarantee harmony—to ensure that everyone ‘gets along’— is entirely typical for Nordic culture, and given the growing immigrant communities within the Scandinavian countries, one might argue that it was merely a matter of time before this eventuality occurred.

Secondly, it means that Scandinavian countries operate in accordance with neorealist theory and political assumptions. By exhibiting willingness to compromise the rights of their citizens, and therefore to some extent their very sovereignty, Sweden and Denmark are showing themselves to be savvy geopolitical players that can break or remake the rules as the situation demands. The flood of condemnations that have come in from OIC countries against Sweden are, after all, just as much an indicator of the government’s desire to satisfy the religious sensibilities of their voting populations as they are indicators of a sincere anti-blasphemy attitude from political leaders in those regions. By compromising its freedoms of speech and expression as a means by which to satisfy its international partners, Sweden and Denmark are revealing themselves to be far more ruthlessly utilitarian, and far less naïvely socialistic, than most observers might think.