New developments in the war in Ukraine, namely the arrival of increasing numbers of freshly mobilised Russian troops to the frontlines, Russian advances in the Donbas—particularly the fall of Soledar—and a tentative new offensive in Zaporizhzhia region have prompted calls for Western powers to supply heavy armour to prop up the faltering Ukrainian war effort. Although Britain took the lead by promising to deliver fourteen Challenger 2 main battle tanks, Germany was expected to shoulder most of the burden by supplying the bulk of the roughly three hundred tanks the Ukrainian military command and President Zelensky requested.

At the time of this writing, Berlin refuses to oblige and, according to unconfirmed, but persistent press reports will only agree to send its Leopards if the USA delivers M1 Abrams MBTs first. The German leadership, and Chancellor Olaf Scholz in particular, have come under harsh international criticism as a consequence. Those attacks, however, ignore two very pertinent lessons from history.

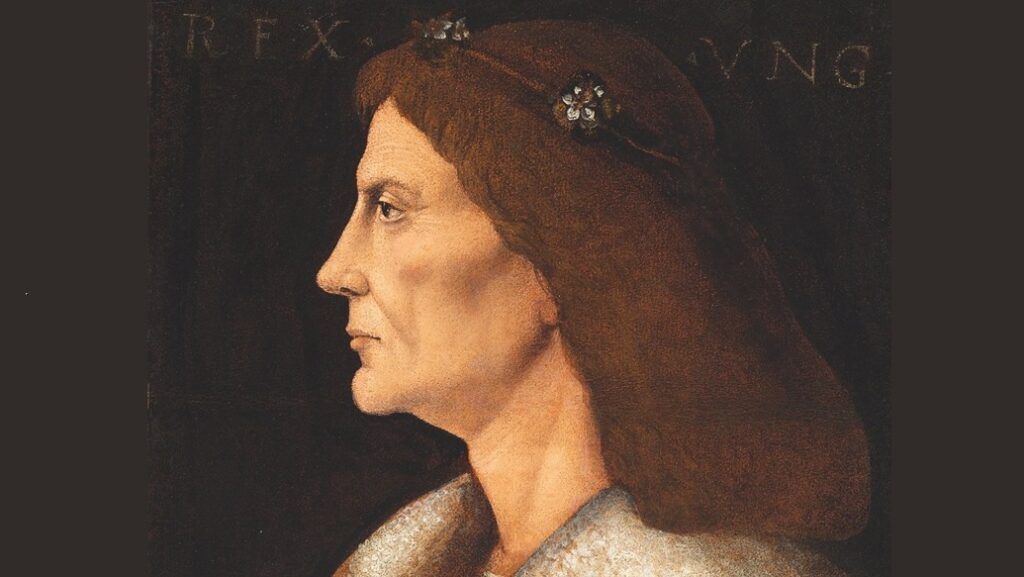

Another German tank, also named after a big cat, has a notoriously ugly history of fighting the Russians in Ukraine. Parallels with Second World War era Tigers were immediately noted by Russian propaganda, but also by other observers around the world, less keen on what they consider a gung-ho Western attitude to flooding weapons into a horrible conflict.

Committing Leopards to Kyiv would no doubt be used by the Kremlin to inflame passions at home,

drawing a false equivalence between the Nazi tanks in the Second World War, and Germany’s role in today’s war of Russian aggression against a sovereign neighbour.

There should be no doubt: images of German tanks making their way across Ukrainian mud to kill Russians would increase the popularity and legitimacy of President Putin’s war, especially if we consider the propensity of certain Ukrainian formations to decorate their vehicles with WWII-era German insignia. It would be a public relations coup for Mr. Putin, one upon which he could base not just a renewed effort of recruiting volunteers for the Russian army, but also a second wave of mobilization, should he so choose. For Germany, this would be a disaster on par with former chancellor Angela Merkel’s seeming admission that the Minsk Accords were designed to mislead the Kremlin and buy Kyiv time.

Then there is German public opinion to consider.

A recent YouGov poll indicates that a plurality of Germans (43 per cent) oppose sending tanks to help Ukraine,

with only 39 per cent expressing support for such a scheme. Historical memory among voters seems to be stronger than among leading politicians of the Greens, who were all in for ‘freeing the Leopards’. Socialist Chancellor Olaf Scholz, however, had to contend with a deeply divided public opinion on an issue replete with dark memories, and one that goes against most Germans’ instincts to stay out of wars. Based on that alone, the criticism levelled at him seems overblown.

Beyond the Second World War, there is another historical parallel, that should instil caution in all Western—not just German—decision-makers. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union possessed a formidable conventional military, which at times throughout the 40 years outnumbered Western forces in Europe more than three-to-one. In the event of a Soviet invasion, NATO’s defensive strategy at the time called for rapid reinforcements from North America and dogged defence of Western Europe’s frontiers.

But were the Red Army’s armoured formations to break through the front and attempt a rapid advance towards the European heartland, a limited tactical nuclear strike was to be launched, in the hopes that it would make it impossible for the Soviets to supply their forward positions, and that it would demonstrate with stark clarity that NATO, including the USA, was ready to risk it all to protect the members of the alliance. This, in fact, served as the rationale for NATO’s ‘first use’ policy, which is in effect even today.

It is not difficult to see that the current predicament mirrors the situation during the Cold War with the roles reversed,

and a smaller theatre of operations: Ukraine instead of Western Europe.

Back then Russian armour had an overwhelming numerical advantage, today—it is assumed—Western tanks have an insurmountable technological superiority. It seems reasonable to posit that Russian planners are thinking about the possibility of Western main battle tanks breaking through their front lines in much the same manner as NATO strategists contemplated the opposite during the Cold War and that they are coming to a much similar conclusion.

Throughout this conflict, nuclear sabre-rattling has been a feature of Russian propaganda, with fluctuating intensity. A recent belligerent remark by Mr Vyacheslav Volodin, the speaker of the Duma that threatened with ‘global catastrophe’ shows that nuclear blackmail is once again on the uptick. However, given the historical lesson of the established NATO doctrine during the Cold War, one should not dismiss it as a mere bluff.

As Frank Furedi—someone who needs no introduction for the readers of Hungarian Conservative—often points out, despite widespread attempts by the progressive left to wipe out national memories, to sever the bonds that tie Western societies to their pasts, attempts to subvert the teaching of history in the classrooms by introducing neo-Marxist dogma like critical race theory,

‘history cannot be unmade and that sooner or later we have to come to terms with its inescapable truth’.

Indeed, a strong argument can be made that we wouldn’t be here if the West approached the war in Ukraine with a strategy more grounded in historical wisdom. It is not yet too late to correct this error, but that requires a more sober discourse when a top politician, like in this case, Chancellor Scholz, makes a cautious step back, informed by prudence, and at least a vague recollection of the past.