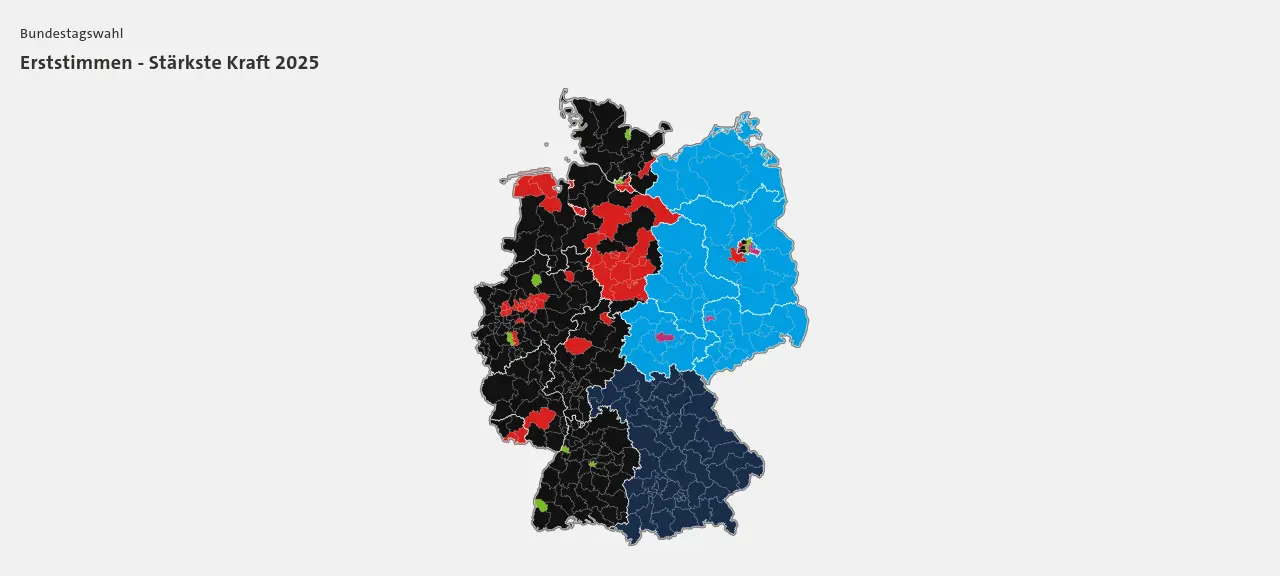

The emerging sovereigntist era is causing panic. Most affected are progressives and liberals in former West Germany, who despaired at the national-conservative AfD surging to record highs in the German elections. From its East German stronghold, the party secured 21 per cent of the vote, trailing only the CDU, which garnered 24 per cent but ended up with 33 per cent of the seats due to the electoral system. Not that AfD has a real chance of joining the government; it remains behind the cordon sanitaire, known in Germany as the ‘Brandmauer’, the ‘firewall’. But the chaos is palpable nonetheless. A firewall? It is burning on both sides of that wall—the entire liberal worldview is ablaze.

This turmoil is due less to the election results themselves, which were predicted accurately in advance, than to the cascade of catastrophes that shaped this election season: jihadist terrorist attacks, deindustrialization in the German economy, and America’s bullying attitude towards Ukraine. To top it all off, Elon Musk and Vice President JD Vance criticized Germany’s firewall. German elites were stunned. Those cronies of the tyrannical Trump—they are lecturing us?

‘It is unreasonable to taint a democratic party in the 21st century with the 20th century’s totalitarian chapter’

Understandably, German elites are in an uproar. But the panic over AfD itself seems exaggerated. I wouldn’t vouch for every AfD party member, but even the most controversial AfD politician would hardly stand out with equivalent nationalist rhetoric in Italy, the United States, or my home country of the Netherlands. Of course, the heightened sensitivities around AfD are due to the memory of Nazi Germany. Still, it is unreasonable to taint a democratic party in the 21st century with the 20th century’s totalitarian chapter.

At the same time, we are in the midst of a very real shift that raises valid concerns. The emerging sovereigntist era unleashes nationalist energies that must be tempered and channelled constructively. Currently, Trump’s ‘America First’ is swinging like a wrecking ball through the West’s liberal order, even jeopardizing its economic fabric with destructive tariffs. Also, in all EU states, nationalist impulses must be rendered congruent with the spirit and structure of European cooperation.

Also, a new zeitgeist is unfolding, upending our conceptual world and even shifting how we imagine space and time.

Spatially, we were part of a ‘Western world’. The idea of the West as a political space emerged around 1900, replacing the concept of ‘European civilization’. Initially used negatively by anti-Western intellectuals in Russia, Germany, and Japan, it gained traction as a positive self-description during the Cold War. The primary associations with ‘the West’ were liberalism and American leadership—both of which are now crumbling. America no longer wants to be in a fixed team formation with Europe; it merely wants to be a great power. Its self-image is shifting away from us. Under the influence of woke leftism over the past two decades, historical bonds with Europe, once a profound source of prestige, have in the American humanities been increasingly framed as a legacy of racist ‘whiteness’. This distancing from the mother continent laid the cultural groundwork for the current political breakup. Now, Trumpism is actively dismantling the liberal West.

‘After all, if we are the future, what is left to think about?’

Shocking, certainly. But the collapse of ‘the West’ also opens up intellectual possibilities. As ‘Westerners’, we struggled to critically reflect on our politics and culture because we believed ourselves to be the world’s future. After all, if we are the future, what is left to think about?

Hence, the rise of the sovereigntist era also morphs our sense of political time. Since the late 1980s, the dominant Western ideology has been a liberal end-time imagining: Fukuyama’s ‘end of history’. In 1989 American philosopher Francis Fukuyama argued that modernity’s ideological struggle would culminate in an eternal liberal hegemony—just as Napoleon once predicted that all states on earth would eventually adopt ‘liberal ideas’. Fukuyama is often mildly mocked; everyone assumes they are smarter than him. Yet many of those smarties unconsciously subscribe to a moderate version of his thesis, which holds that though not everyone will become liberal, liberalism eternally defines the meanings of ‘democracy’ and ‘future’. It is this mindset that allows them to dismiss any democratic nationalism—including AfD—as an anti-democratic threat pulling us back into a dark past.

But as the ‘end of history’ ends, it emerges that there is no single final truth. Europe contains multiple legitimate interpretations of democracy and the rule of law, rooted in different but equally valid historical imaginings. The frequent claim that national conservatives ‘refuse to learn from history’ wrongly assumes that the horrors of the mid-20th century left us with only one lesson: that nationalism led to Hitler, war, and genocide; that nationalism is inherently anti-democratic; that national democratic majorities must be tightly constrained within legal and supranational frameworks.

‘Nationalism is the historical foundation of modern democratic nation-states’

But that is not the lesson in East Germany—the AfD heartland—or in Visegrád countries like Hungary. Nor was it what most West Europeans believed in the 1950s and 60s. Back then, the prevailing view was that European nations had resisted two totalitarian imperialisms—Nazism and Stalinism—; the latter of which was an internationalist ideology. National resistance heroes were celebrated in France, the Netherlands, and elsewhere. The Hungarian freedom fighters of 1956 gained widespread admiration: they defended democracy against totalitarianism. That made sense since nationalism is the historical foundation of modern democratic nation-states; it introduced the egalitarian idea that everyone, from high to low, is part of the nation.

The anti-nationalist ‘lesson’ that displaced this original insight arose from a liberalism that spread in the late 20th century from West Germany and the European Commission. Jürgen Habermas, the star philosopher of the German Federal Republic, had argued in the 1950s that Germany’s national identity needed cleansing, but by the 1990s he rejected the principle of ‘national self-determination’ altogether—for all European states.

The tragedy is that the East German demonstrators who, in 1989, chanted: ‘We are the people!’ had to learn, after Germany’s reunification, that the new liberals in the West had a different ideal of democracy. In liberal discourse, ‘democracy’ now refers more to the legal and technocratic restraints on democratic majorities than to the will of the majority of the people shaping policy outcomes. This is the liberal inversion against which national-conservative parties like AfD, Rassemblement National, Geert Wilders’ Freedom Party, and Fidesz rebel.

For my Dutch compatriots and my German liberal acquaintances, much of the above is an entirely unfamiliar perspective. This is because the liberal end-of-history ideology systematically brands alternative views of democracy and history as ‘authoritarian’, ‘far-right’, or ‘anti-democratic’, as political scientist Philip Manow lays out in his masterpiece Unter Beobachtung (2024).

‘Loving Europe means loving its multiplicity’

But the liberal stigmatization system is faltering. Europe can think once more! And we must think—because we can no longer rely on American protection.

It is time for the states and peoples of the EU to stand firm together—in diversity, including historiographical diversity. Hannah Arendt observed that Europe is ‘the heir to many pasts’. Good Europeans do not place other people’s pasts behind firewalls. National conservatives, East Germany, and the Visegrád states belong to a democratic Europe, as do Europe’s many migrant communities and ethnic minorities, who also bring their own historical perspectives. Loving Europe means loving its multiplicity. We are Europe!

Related articles: