President Donald Trump, on his self-proclaimed ‘liberation day’, imposed sweeping tariffs of at least 10 per cent on almost every product that enters the U.S. from almost every country—China in fact got hit with a 34 per cent tariff—with the aim of keeping jobs within the American homeland. What the president has done is reverting to the American ‘protectionism’ of the 19th century, which economists call the Hamiltonian Statecraft. Yet, his across-the-board tariffs have even been inflicted on America’s closest allies, like the European Union and Israel, thus sparking a trade war.

China, for example, struck swiftly on Friday, with tit-for-tat tariffs of 34 per cent, after speculation that it might coordinate its response with its neighbors Japan and South Korea. And the European Union is now warning countries that find themselves priced out of the American market not to dump cheap exports in its market. Moreover, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is set to be the first world leader to hold in-person talks with Trump about the tariffs as more than 50 countries had reportedly reached out to start negotiations. The president’s measures are nothing other than a reverting to the American ‘protectionism’ of the 19th century, which economists call the Hamiltonian Statecraft.

The rationale behind this measure, as explained by a White House official, is to keep the U.S. from being ‘cheated’ in the global market: ‘These tariffs are customized to each country, calculated by the Council of Economic Advisers…The model they use is based on the concept the trade deficit that we have is the sum of all the unfair trade practices, the sum of all cheating.’

The long-term aim is to get the U.S. $1.2 trillion trade deficit and the largest country deficits within that down to zero. Yet, while the equation was simplistically designed to target those countries with surpluses, as opposed to those with recognizable quantifiable trade barriers, there are major risks involved in re-introducing the Hamiltonian protectionist policy.

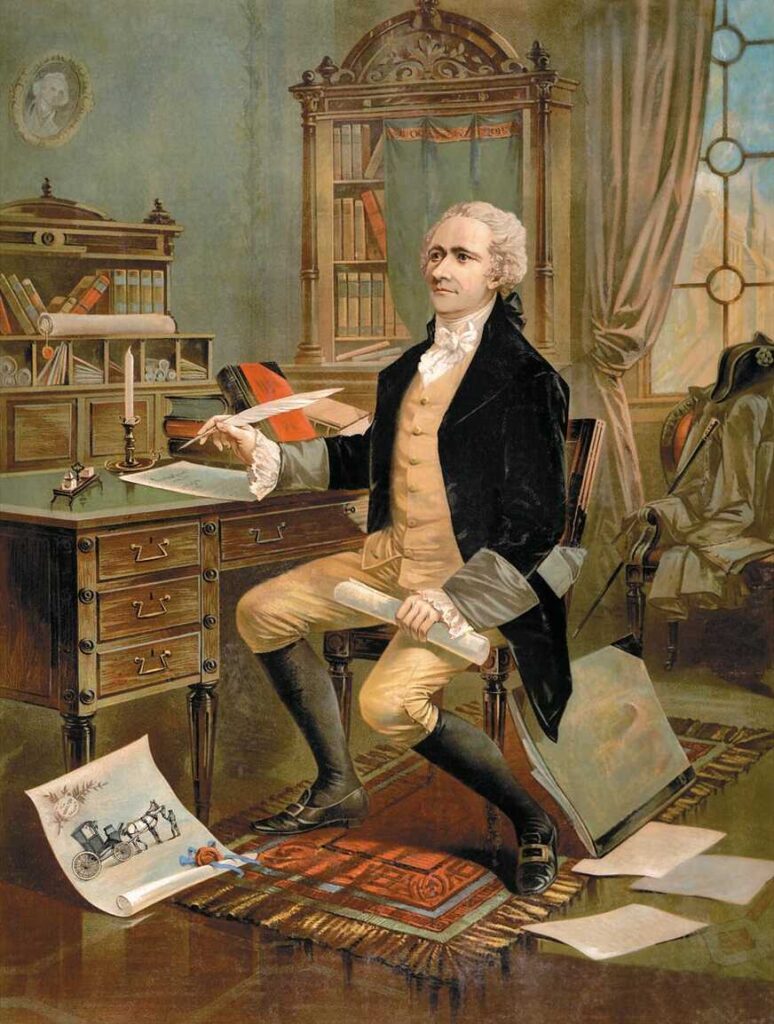

The Hamiltonian Statecraft

Based on the stratagem of the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, such policy is one of protecting domestic industries against foreign competition by means of tariffs, subsidies, import quotas, or other restrictions or handicaps placed on the imports of foreign competitors.

Subsequent to the dire, if not feeble situation of the U.S. after it had gained its independence from Great Britain, Hamilton sought to cultivate the nation’s economic strength, which in turn would become the foundation for both American national security and sustained growth. He envisioned a set of economic, commercial, and financial institutions, which included a flourishing merchant fleet, a domestic manufacturing base, and a national bank that would channel and multiply the nation’s economic power. However, even he knew that without constant revenue, such power was only nominal.

Hamilton was a proponent of free trade among nations. Yet, because the European powers relied on trade barriers to protect their domestic markets and industries, the U.S. was in a disadvantageous position. To combat this, he demanded that American leaders would need to take matters into their own hands:

‘Tis for the United States to consider by what means they can render themselves least dependent, on the combinations, right or wrong of foreign policy.’

Hamilton, thus, proposed a pragmatic grand design that would enable the growth of U.S. commerce, the prosperity of American patriotism, and enlightened realism in foreign affairs. This led President George Washington to sign into law the Tariff Act on 4 July 1789—it was the first major piece of legislation passed in the U.S. after it ratified the Constitution.

The Tariff Act subjected most imported goods to a 5 per cent ad valorem duty. Many of the commodities which were assigned specific rates had been selected because they were produced within the U.S. As protective measures, however, these tariffs proved too low to be effective.

Eventually, the Hamiltonian protectionist policy came into full force towards the end of the 19th century during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age (1865–1896) as U.S. manufacturers bested their British rivals. In truth, it was the expanding American domestic market and not exports to foreign countries that became the impetus for giant corporations in the U.S. to prosper—these large businesses were intimately connected to the then Republican Party. Despite heavy opposition, President Woodrow Wilson, seeing the great corruption and the fleecing of the average American citizen by the financial elite, introduced the federal income tax in 1913. Subsequently, tariffs would no longer to be the main source of revenue for the U.S. government.

A Probable Outlook

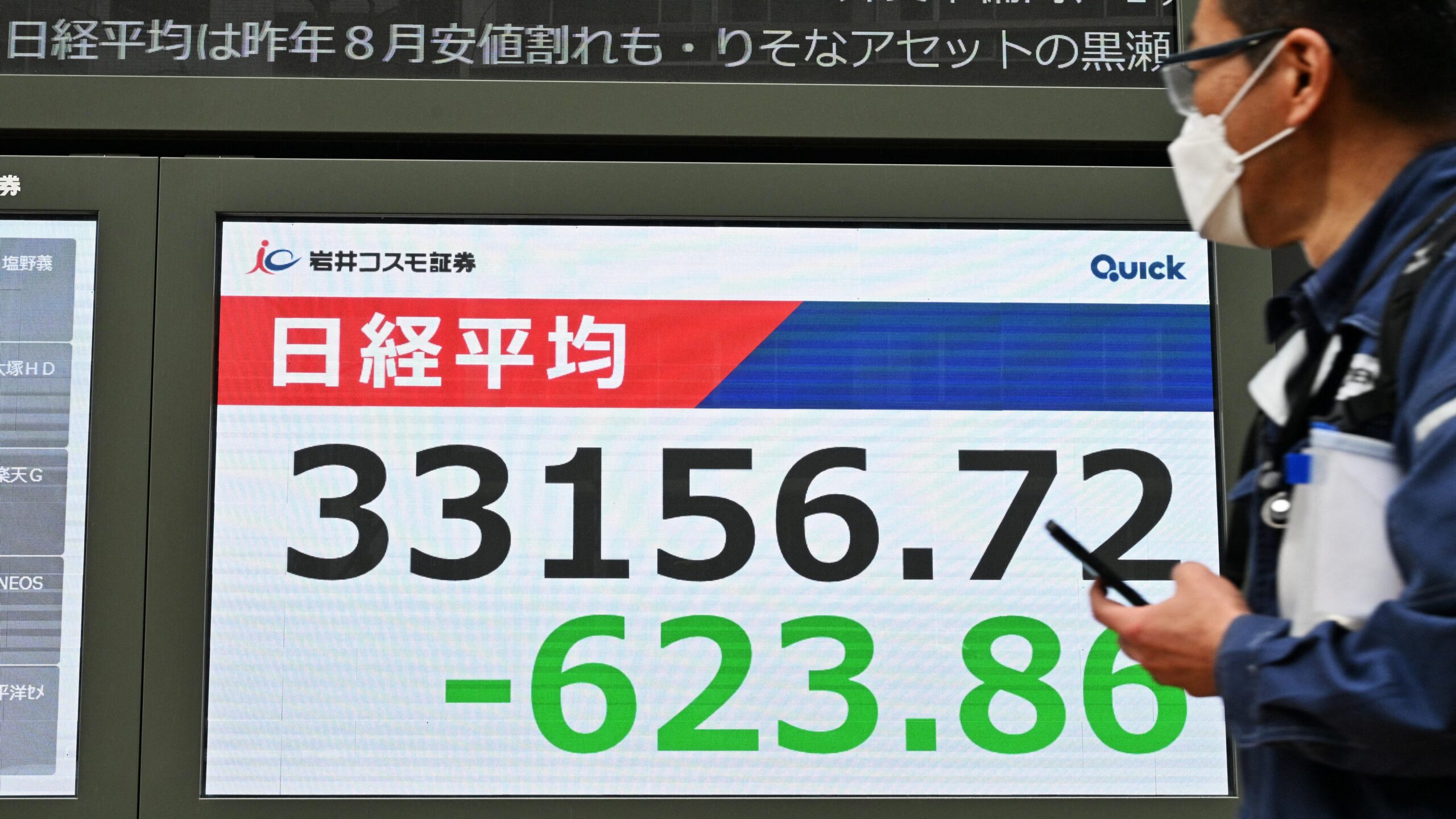

The instant reaction on Wall Street vaporized more than $6 trillion of wealth in two days; the Dow Jones Industrial Average sank 2,231 points, or 5.5 per cent, taking the S&P 500 back to its levels in February 2024. In addition, oil prices plummeted by 14 per cent in two days, bludgeoning frackers. It has been the steepest economic decline since 2020.

Trump’s global trade war has significantly raised the bar for the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates, as tariffs risk worsening an already knotty inflation problem while also damaging growth. Just prior to ‘liberation day’, The Wall Street Journal, in an op-ed piece titled ‘Trump Takes the Dumbest Tariff Plunge’, stated: ‘Mr Trump is whacking friends, not adversaries. His taxes will hit every cross-border transaction….Is this how the new Republican Party plans on helping working-class voters?’

‘Some economists...are not so pessimistic, saying that tariffs will restore American manufacturing’

Today’s world is altogether different, to say the least, from the one of a few decades ago, let alone from the time of Alexander Hamilton. We are in a globalized world that has been both steered and championed by the U.S., not in one in which the U.S. was trying to make its mark.

In a note titled ‘There Will Be Blood’, JPMorgan’s head of economic research, Bruce Kasman, raised the probability of a global recession to 60 per cent from 40 per cent. The bank expects U.S. gross domestic product to contract 0.3 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2025 from a year earlier; it previously expected 1.3 per cent growth. Unemployment will reach 5.3 per cent next year, JPMorgan says.

Some economists, however, are not so pessimistic, saying that tariffs will restore American manufacturing. They point out that when Barack Obama became president, he imposed a 35 per cent tariff on Chinese imports from 2009 to 2012, for dumping tires into the American market; Biden also kept Trump’s first-term tariffs on China in place.

Other economists say that a trade war will only hurt low-income exporters of commodity goods, which have little leverage to respond to Trump, such as Nigeria, which was hit with a 14 per cent tariff, and Kenya and Ghana, both hit with 10 per cent.

I, myself, am not an economist. Thus, I dare not be pretentious to predict what the inevitable outcome of this frenzy will be. I can, however, foresee, when this is all over, an op-ed piece titled: ‘Trump, the Man Who Restored the American Republic’ or ‘Trump, the Man Who Drove the American Republic to Its Grave’. If I were a betting man, and I hope to be proven wrong, I would opt for the latter, but only time will tell.

The views expressed by our guest authors are theirs and do not necessarily represent the views of Hungarian Conservative.

Related articles: