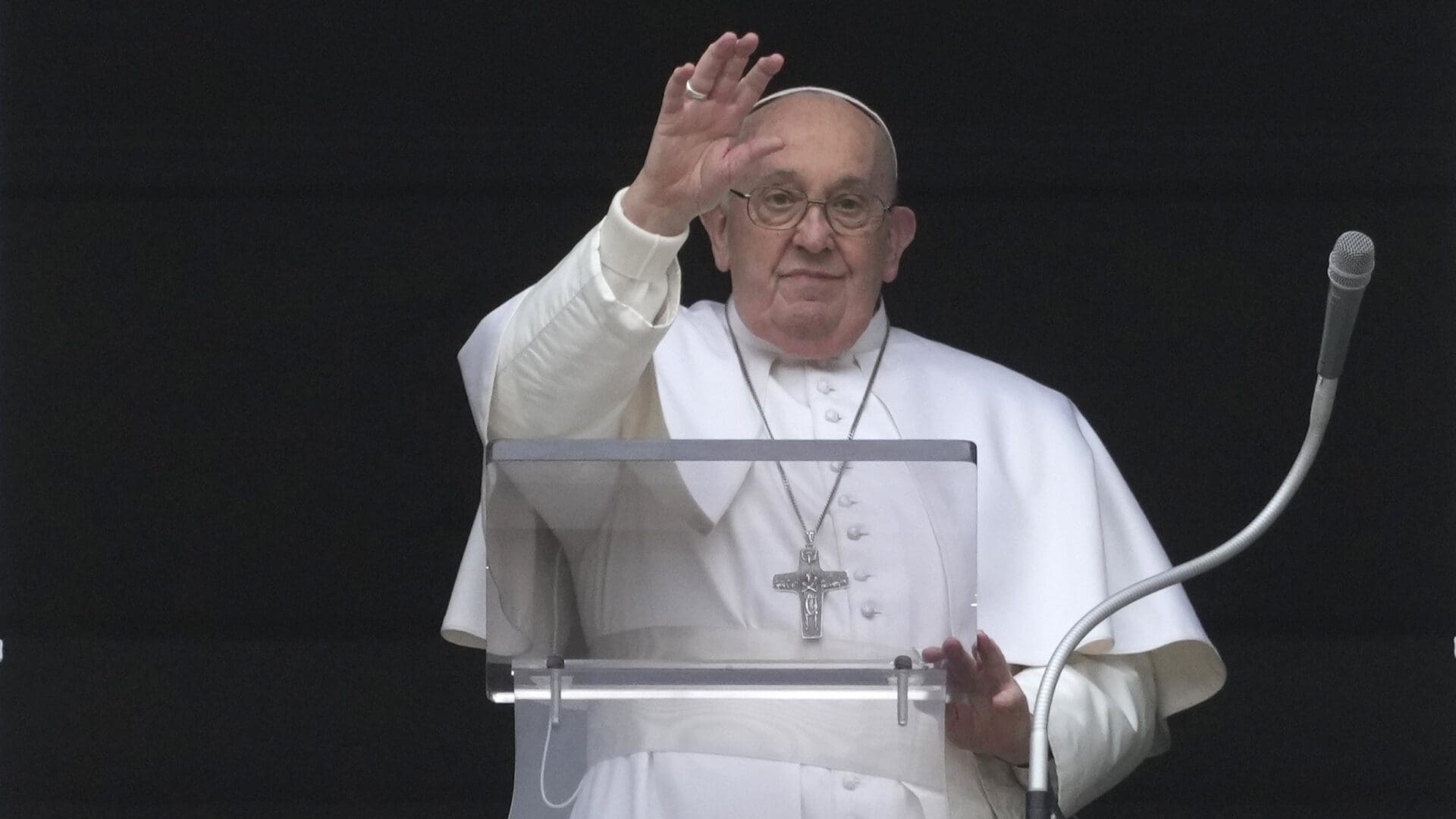

Pope Francis, during an interview with Swiss broadcaster RSI last month, though partially aired this past Sunday, said that Ukraine, facing a possible defeat, should have ‘the courage of the white flag’ to negotiate an end to the war with Russia and not be ashamed to sit at the same table to carry out peace talks:

‘When you see that you are defeated, that things are not going well, you have to have the courage to negotiate. Negotiations are never a surrender.’

The Pontiff also reminded that some countries have offered to act as mediators in the conflict.

‘Today, for example, in the war in Ukraine, there are many who want to mediate’, Francis said. ‘Turkey has offered itself for this. And others.

Do not be ashamed to negotiate before things get worse.’

The Pope’s comments were met with harsh criticism from Ukraine. Not only did Ukrainian officials say that they would never surrender but went so far as to accused Pope Francis of siding with Russia. Matteo Bruni, the Director of the Holy See Press Office responded by saying the Pope’s use of the term ‘white flag’, indicates a cessation of hostilities, a truce reached with the courage of negotiation. This is something Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has ruled out unless Russia restores its occupied territories, including Crimea, which the Russian leader will not do.

‘Every war is ironic because every war is worse than expected’, said the American cultural and literary historian Paul Fussell. ‘Every war constitutes an irony of situation because its means are so melodramatically disproportionate to its presumed ends.’

Fussell, in his book The Great War and Modern Memory pointed out that there had always been a profound rift between a romanticism that viewed going to war as the altar of noble chivalry and valor, and the consequential disenchantment of the unanticipated savagery of trench warfare.

The Willingness to Fight

One month after the invasion, according to The Washington Post, polls showed that Russians have consistently expressed greater willingness to sacrifice their material well-being in the interests of their country’s military goals—and are more willing to accept conflict with other nations to defend Russian interests. Have things changed?

It has now been over two years since Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered his troops to invade Ukraine. Since then, the Russian Federation has demonstrated that its military power is not as mighty as the Russian leader had bragged it to be prior to his invasion. Indeed, notwithstanding the Russian victories over the past year, which have been the capture of two small towns in the Donbas—these are the only Russian successes—it took Russian soldiers months to do so and cost of tens of thousands of casualties. At the same time, the Ukrainians, who are greatly outnumbered, have inflicted severe damage on the Russian Black Sea fleet.

While the number of confirmed dead on the Ukrainian side is 31,000, the current rate of Russian casualties estimated by US intelligence can be as high as 315,000 killed and wounded. Prior to the invasion, Russia had a ground force strength of about 360,000.

One of the reasons European member states, as well as those of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), with the exception of Hungary and Slovakia, have continued to provide arms to the Ukrainians is to prevent Russian forces from entering a country that is part of the Alliance.

Indeed, early this month European Commission President Ursula Van von der Leyen appealed to the European Parliament to take more responsibility to strengthen European security in case Mr. Putin decides to expand his military aggression into other parts of Europe:

‘The threat of war may not be imminent, but it is not impossible. And the risks of war should not be overblown, but they should be prepared for’, she said. All things being equal, it would be futile for Russia to do so, and Mr. Putin knows this.

In a recent article by Voyennaya Mysl (Military Thought), Russian military strategists admitted that Moscow would not be ready if NATO attacked, that is if the United States does not pull its 1.5 million troops from the Alliance as presidential hopeful Donald Trump threatened to do if NATO members not fulfilling financial commitments to the Alliance.[1]

In truth, EU countries outweigh Russia in terms of numbers, weaponry, and military spending, although mobilizing these resources is an altogether different challenge—and this would be to Moscow’s advantage.

Russia’s defense budget has tripled since 2021 and will consume 30 per cent of government spending next year, which amounts to six per cent of its GDP (more than eight per cent when combined with spending on national security). This is more than the 3.8 per cent of GDP that the United States spent during the Iraq war.

Yet Kyiv knows that its soldiers cannot continue fighting the Russians without continued U.S. assistance and given the recent reticence of US lawmakers to supply them with money and weapons, time may indeed be running out for the Ukrainians.

Russian missile attacks have grown more experimental and complex since 2022, and Ukraine’s interception rates have declined as a result. In early January, Ukraine admitted that lower-altitude air-defense systems around Kyiv could withstand only a few more large attacks.

Whose Side Is Time On?

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán at the Antalya Diplomatic Forum on 2 March stated:

‘If you think that time is on the Ukrainian and he Western side, and continuing the war can provide military success for the Ukrainians, it’s reasonable to continue. If you think that time is more on the Russian side, and continuing the war would bring more success to the Russians, for the Ukrainians it is better to stop now. I belong to the second camp.’

The truth of the matter is, given the lack of transparency by Moscow, and the overly pro-Ukrainian reports by the U.S. government, especially given its lies in its wars in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan,

trying to have a precise and clear idea of what is the military situation in Ukraine is like trying to find a needle in a haystack.

Senior Fellow in the Russia and Eurasia Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Dara Massicot says that Russia’s military’s long-term weaknesses will not matter if the U.S. ceases to supply Ukraine with the necessary military arms—the Ukrainians are already rationing their ammunition. Ukrainian frontline soldiers are in mounting jeopardy, not because they lack the will to fight or do not know their enemy’s weaknesses, but because of shortfalls in weapons and manpower.

Is Pope Francis correct to suggest that this is a war Ukraine cannot win, and so, it should start seeking a truce with Russia? Ending the war, even a ceasefire, is not an act of cowardice, especially when there is no end in sight. History, at times, breeds a vacuum. All one has to do is look at the American involvement in Iraq and Vietnam, as with Russia’s engagement in Afghanistan. The results were far from gallant, they were in fact calamitous. Regrettably, those who call the shots are not courageous enough to admit a cold hard fact: the longer this savage war continues, the worse it will be for both sides.

The views expressed by our guest authors are theirs and do not necessarily represent the views of Hungarian Conservative.

[1] NATO member states do not pay to be a part of the Alliance and do not owe it anything other than contributions to a largely administrative fund. Under pressure from the Obama administration in 2014, NATO members agreed to move ‘toward’ spending 2 per cent of GDP on national defense by 2024. The 2 per cent quota is a benchmark that each member state should spend on its own defense in order to be able to contribute to the joint defense of the Alliance. This, however, is voluntary, and there is no debt or ‘delinquency’ involved as Trump hypes it up to be.