Hungary and the peoples of many other countries are mourning Queen Elizabeth II as if we were all members of the Commonwealth, and she had been our head of state—a crowned head.

Of course, the British ruler and her whole family are also internationally acclaimed celebrities in our modern times. And yet, the question arises:

Why are we so emotional about the death of the monarch of another country?

The other similarly grand royal family of the Western world is the House of Bourbon of Spain, but are we equally interested in Juan Carlos I, or his son he abdicated in favour for, Felipe VI, not to mention the Dutch, the Belgian, the Swedish or the Norwegian rulers?

The attention bestowed on the late British queen can at least partly be attributed to her status as an international celebrity. But Elizabeth II and other rulers are not at the centre of interest merely because they are influential and well-known figures.

It seems that we relate to monarchs in a more sentimental (or more hostile) way than to presidents of republics. The same type of attention is directed to (what is left of) the aristocracy. In Hungary, we have abolished the estates and the orders, and have annulled the ranks of nobility, but we keep being romantically attracted to the remaining representatives of the aristocracy. One wonders why. Well, I have a few educated guesses.

It is perhaps that monarchs are surrounded by an air that other politicians are not.

There is nothing that people can relate to more than to continuity represented by a family and its members

This is because the fact that they are not elected but inherit their throne represents a continuity, via their families, originating in the misty past; and not abstractly so, but in a very concrete fashion, through real people and their very recognisable faces, paintings and sometimes photographs of which are hanging on the walls in royal palaces. And there is nothing that people can relate to more than to continuity represented by a family and its members. The Japanese imperial family, for instance, is more than one thousand years old, and its roots go back as far as the world of the ancient Japanese myths.

Except when we nostalgically reminisce, we tend to talk about monarchies from a utilitarian and democratic standpoint. Beside ideological issues, our problem with monarchies is that they do not fit into the democratic-popular sovereignty logic, as, typically, monarchs are not elected. The monarch embodies an irremovable elite that cannot be replaced (or, rather, in most cases, it can only be removed by force.) Also, what happens if a child whose personality and qualities make them unsuitable inherits the throne? These are reasonable concerns.

As a result, wherever in the Western world there are still monarchies, they have been eviscerated and turned into ceremonial institutions. Of course, monarchies may retain their symbolic power regardless.

However, those who seek to define the role of monarchies in such democratic and utilitarian ways, miss the point, as they are looking in the wrong place. A monarchy is the expression not of a mechanical, but of an organic concept of society, where the ruling family is the head. And one does not change one’s head. Another aspect some have pointed out is that rulers can think long term and can embody the unity of the nation (or of the peoples they rule over) precisely because they were not elected, and they are not limited by daily political struggles or by elections every few years. The heirs to the throne grow up around the ruler, in her or his court, and thus are groomed to do politics and to reign. That means plenty of experience on the job, much more than politicians who acquire those skills as adults have.

But let’s nail it down: conservatism is not necessarily monarchist.

As conservatism emphasises man’s imperfection, it holds that there is no perfect form of government. Several systems can be good or less good, while some are categorically bad (such as totalitarian dictatorships.)

At the same time, it is understandable that conservatives have a predilection for a form of government that their ancestors had defended—and which is a symbolic expression of their concept of society, an imperfect but established order. Conservatives will often reply to inquiries as to why they are attracted to monarchies by saying ‘just because’: this is what we are accustomed to, a monarchy is part of the tradition, and it makes no sense trying to start a rational debate about it.

I personally would not be such a defeatist. Continuity, organic society, rising above daily political struggles and the symbolic embodiment of the nation are all important. But the essence of monarchies lies elsewhere.

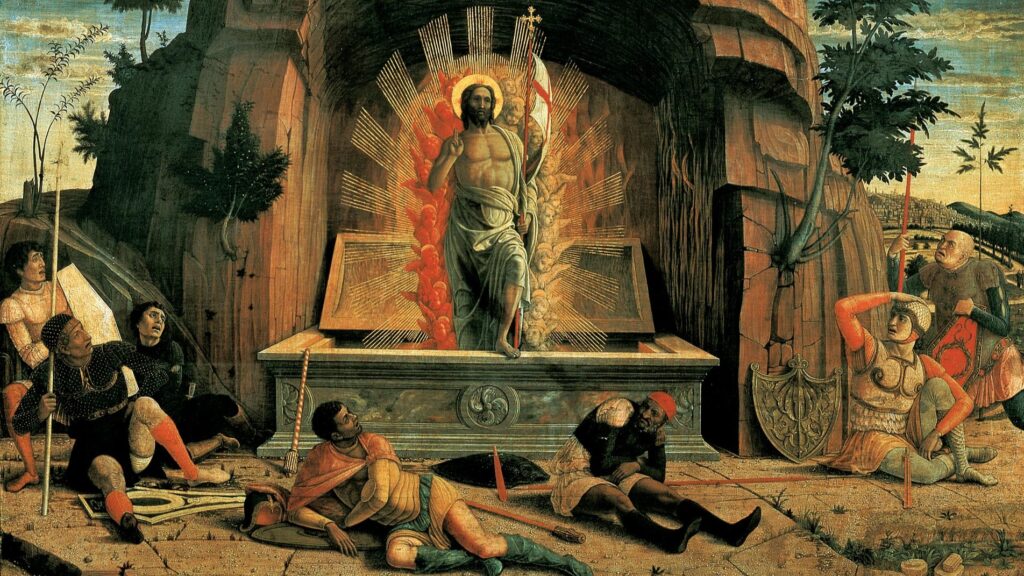

Monarchies are fundamentally sacral institutions. The ruler is a sacral person, who mediates between his or her people and the transcendent reality

That was the way monarchs were looked at in the Middle Ages—the ruler was almost a member of the clerical estate, and the coronation was a sacral act.

Modernity, however, liberated society and politics from the close intertwinement with the sacred, and, by making them utilitarian, rationalised them. In other words, it desacralized and demystified them. On the other hand, as Tamás Molnár also pointed out in his book entitled Twin Powers: Politics and the Sacred, politics and the sacred have always been intertwined during history. Their separation (secularisation) was brought about by the Enlightenment. Secular logic does not understand, does not grasp the gist of the monarchy.

This does not mean that monarchies have no place in the modern world, and that we should just dismiss them as out of context and irrelevant. It does the postmodern West good if it is a political public institution, a personified public institution, and not an impersonal bureaucracy that reminds it of the sacral, transcendental dimension it depends on. It is not just the pro-equity, horizontal dimension that exists, but the vertical one as well—one can look upwards, too. The monarch and her or his family is a sign, a warning, its existence elevates us above the everyday, into a more sublime, more majestic world, despite the occasional scandal that mars the dynasty.

As Otto von Habsburg—who, as Otto II, could have been our king reigning even longer than Elizabeth II in an alternative reality—said in his book The Social Order of Tomorrow: the most ancient rulers, the kings of the Holy Scriptures, were chosen from among the judges; French king St Louis also regarded jurisdiction as his most noble duty. In medieval times, tradition and the local right to self-determination strongly restricted the legislative power of kings (medieval monarchies were markedly localists). At the same time, the ruler’s most important task is not to pass verdicts in current legal debates, but to ‘stand guard over the function of the state and natural law. Being the supreme judge is first and foremost making sure that that all laws are in harmony with the basic principles of the state, that is natural law.’

Ruling ‘by the grace of God’ does not mean that the ruler is superior to others; it rather expresses ‘service and duty’

Otto von Habsburg added: the most profound justification of hereditariness is that the legitimacy of the monarch derives not from some social groups (whether a class or a camp of voters), but ‘solely from God’s mandation. Ruling “by the grace of God” does not mean that the ruler is superior to others; it rather expresses ‘service and duty’. What’s more, ‘it would be mistaken on the part of a king ruling from God’s grace to regard himself an exceptional creature.’ Authority deriving from divine grace ‘must always remind him that it is not his merits that he owes his position to’ and that ‘he has to continually prove his fitness in the relentless service of justice.’ The ruler transmits God’s grace to his people.

Monarchies are therefore neither better nor worse than republics per definition. In fact, republics are not necessarily democratic forms of government either: republicanism has historically not been too democratic a phenomenon.

So can wishing for and remembering kings be dismissed as unjustifiable nostalgia that excessively embellishes the past? After all, many kings abused their power, used force, sought their own benefit, and subordinated the welfare of their people to dynastic interests. Indeed, power politics and human quality is inseparable from monarchies, too—as from any other form of government.

There is no form of government that saves man from his own bad character

And yet, monarchies are the most suitable to express the sacral dimension, regardless of the monarch’s human qualities. And kingdoms are somehow more intimate and more family-like institutions than republics. Why monarchies make sense has nothing to do with whether they solve political problems better than other forms of government.

It has all to do with their symbolism and their sacral dimension. And the republics of the Western world watch the remaining monarchies with awe, whether driven by love or hatred.

So perhaps that is why we are so deeply moved by the death of Elizabeth II: we watch ancient rites opening up the transcendent to us on the telly, from burial to coronation, and check whether Charles III will ask for another pen.

Click here to read the original article