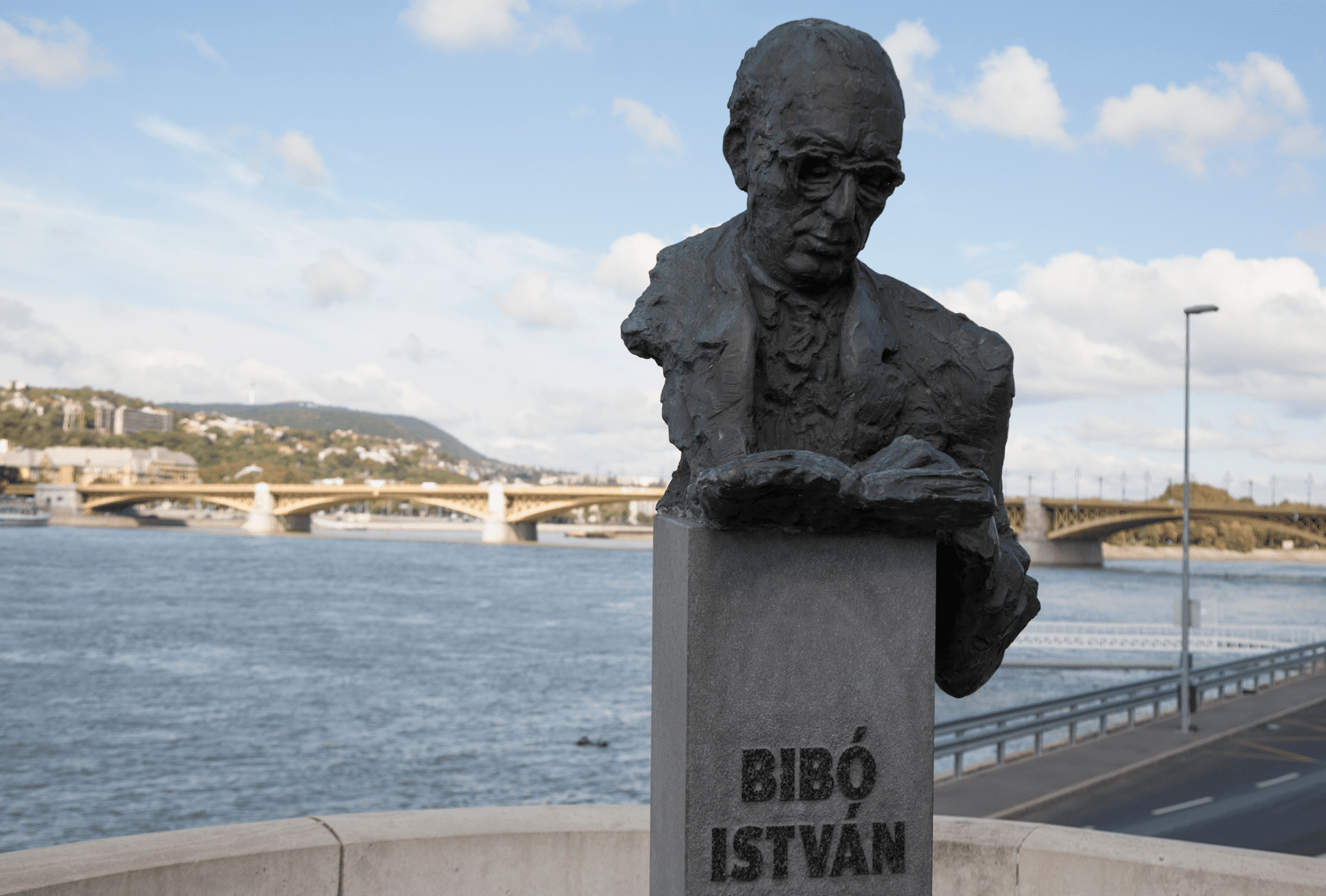

István Bibó (7 August 1911–10 May 1979) was one of the greatest Hungarian political scientists and thinkers of the 20th century. Born into a Calvinist family, he received an excellent education and soon became a renowned academic. Most of his works were published between 1945 and 1948. However, soon after the Communists consolidated their power, he was deprived of his chair at the University of Szeged and heavily censored. From 1948 until his death, hardly any of his written works were published—he mostly expressed his views only to friends and in private conversations. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, he acted as the Minister of State for the Hungarian National Government in the short-lived Third Cabinet of Imre Nagy. He believed that Hungary could become neutral in the same way as Austria and Finland. After the violent crushing of the Revolution, he was sentenced to life imprisonment. He was released as part of the 1963 general amnesty and from then on worked as a librarian at the Central Statistical Office. He died in 1979.

Bibó’s funeral became one of the first significant public opposition events in Hungary under state socialist rule. The democratic opposition seemed to be greatly inspired by his work and suggested reprinting some of his writings. However, the censorship rules of the one-party system did not allow the publication of Bibó’s works under any circumstances, so they had to be released on a samizdat basis. Nevertheless, in 1980, most of the opposition figures of the time, across the board from the extreme right to the centre-left, joined forces to have a semi-legal volume entitled Bibó Memorial Book published to pay tribute to the great thinker. Bibó’s cult and reputation were further strengthened within the ranks of the regime-changing democratic opposition five years later, when one of Eötvös Loránd University’s colleges adopted Bibó’s name. The Bibó István College for Advanced Studies soon became an intellectual centre for university students who were deeply alienated from the Communist system, and some of whom even contributed to the fall of the regime. In 1989, Bibó was looked upon as a thinker who united the opposition in the struggle for the democratisation of Hungary. Today, a single generation later, however, he has little significance for most contemporary Hungarians parties.

One of Bibó’s best-known works is The Jewish Question in Hungary Since 1944. While art and literature in Hungary tried to deal with the issue of the Holocaust after World War II, according to Bibó’s essay, intellectuals remained silent about it. The significance of the essay is therefore that Bibó tried to make up for that silence and confront the question of the Holocaust as a social scientist. He attributed anti-Semitism to a deeply embedded, maliciously distorted view of Jews in Hungarian society, and claimed that to deal with the Holocaust it is not enough to reject anti-Semitism, but the responsibility of the majority society for the Holocaust also has to be taken into account. In Bibó’s view, the main question is what is Hungary’s responsibility in the Holocaust? According to Bibó, it would be very difficult to say what proportion of Hungarians supported or opposed the deportations, and how many people were just confused observers. Instead of trying to balance sins and merits at the national level, all layers of society, and even more deeply, each individual, must assess their own responsibility in the Holocaust, he suggested. Bibó’s essay ends with a note about the future of Hungarian Jewry—he argued that both assimilation and the preservation of a distinctly Jewish identity are possible. Whichever path is chosen, Hungarian society must learn to adapt to the choice and provide the necessary resources for it.

While a key element of The Jewish Question in Hungary Since 1944 is the exploration of how extreme nationalism can corrupt authentic patriotism, the essay is probably more notable for its call for introspection. Bibó passionately believed that everyone should judge themselves and not others in all circumstances. As a member of the Christian middle class, he examined his own and his class’s role and responsibility in the horrible events of WWII. His profoundly moral view is best illustrated by the following quote:

‘It is necessary for everyone to strike a balance for himself, and not to place emphasis on what his merits or excuses are, and how these compensate for his sins or omissions; but simply to focus on what he is responsible for, or what he shares responsibility for. In this way, perhaps later, we will be able to take stock [of what happened during the Holocaust] together as a nation in a cleaner, braver and more responsible way.’

Related Articles: