This article was published in Vol. 2 No. 4 of the print edition

The Devil. Original sin. Man as good. If you would, you could be the Tyrant’s favourite; it is more difficult to love God than to believe in Him. On the other hand, it is more difficult for people nowadays to believe in the Devil than to love him. Everyone smells him and no one believes in him. Sublime subtlety of the Devil. — Charles Baudelaire, Draft of Preface to The Flowers of Evil2

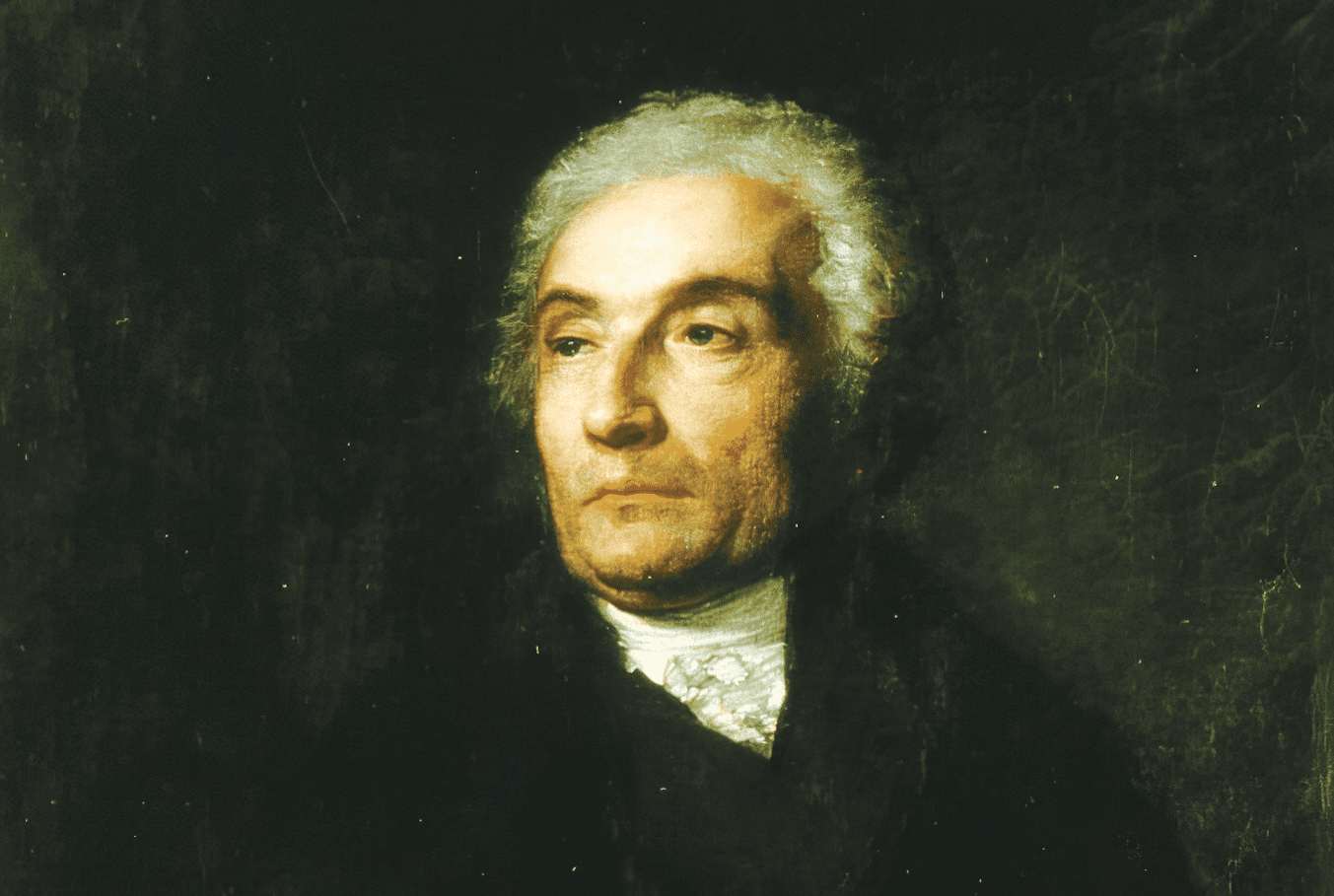

The Bourbon Restoration brought about a burgeoning of intellectual life in France. The thirty or forty years that followed saw thebirth of significantly more intellectual trends and a frenzy of activity by far more authors regarded as influential to this day than those during the Revolution and the Napoleonic era. Yet Joseph de Maistre was not the product of this age. Most of his writings date from much earlier, and his popularity reached its apex later, under the Third Republic.

Even though Maistre belonged to the French cultural milieu, just as his native town of Chambéry had belonged to France since 1792, he remained in the service of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, serving as ambassador to Russia between 1803 and 1817, then as minister of state to the court in Turin from 1817 to 1821.

In Saint Petersburg, Maistre was the impoverished envoy of an inconsequential little monarchy, representing a dynasty displaced to Sardinia. His position was further aggravated after the Treaties of Tilsit (1807), when Emperor Alexander made peace with Napoleon. The four years following 1808 in Russia were marked by reforms introduced by Speransky, when revolutionary principles seemed to have taken root. Yet his time in emigration confirmed Maistre’s assessment that ‘one cannot be more unfortunate than the one who has never experienced misfortune, for he may never be certain of himself and may never know the real worth of his own self. For the man of virtue, suffering is what battle is for the soldier: It will multiply his virtues and hone them to perfection.’3

Speransky’s reforms ultimately failed, but their spirit catapulted Maistre to the forefront of society and the diplomatic elite of Saint Petersburg. Although he was offered a position by Emperor Alexander in 1812, he never ceased to serve his own country. Short of money, he lived by himself, without his family, until 1814, spending his idle days reading and writing. His Les Soirées de Saint-Pétersbourg, which he started writing in 1809, was not published until 1821, shortly after his death, appended by a piece entitled Éclaircissement sur les sacrifices (1809). Almost concurrently, he penned his reflections on the Russian reforms under the title of Essai sur le principe générateur des constitutions politiques et des autres institutions humaines (published in 1814). Also during his tenure in Saint Petersburg, he wrote his book Du pape (1819) as well as his Examen de la philosophie de Bacon (published posthumously in 1836).

The status quo ante did not make sense to him as an order that was overthrown by the Revolution

Maistre remained rather uninfluential during his lifetime, and most of his writings were not published until after his death. Although his fellow émigrés did read his Considérations sur la France, he only became truly popular during the Third Republic, when he came to be called, along with Bonald, Lamennais, and Chateaubriand, a prophète du passé4 or an ‘arch-reactionist’.5 Yet Maistre was hardly a prophet of the past. The status quo ante did not make sense to him as an order that was overthrown by the Revolution. French conservatives differed from their Anglo-Saxon counterparts in that they accorded far less importance to tradition, because it was tradition that had provoked a revolutionary response. When they resort to the term, they do not use it in the evolutionist sense (tradition is what has worked well for humanity) but in the perennialist or Catholic sense (tradition is whatever we call eternal truth).

Besides frowning on the Ancien Régime of France, Maistre did not care much for its Savoyard version either. He disagreed with the idyllic description of Savoyard society, and regarded the old order as being beyond any hope of restoration. ‘The project to put all the water of Lake Geneva into bottles’, he wrote in 1793, ‘is much less crazy than to re-establish things precisely on the same footing where they were before the Revolution.’6 For this reason, the counter-revolution ‘will not be a contrary revolution, but the contrary of revolution’.7

Maistre’s various writings may exhibit certain shifts in emphasis, but they became rather internally consistent after 1791. The French Revolution and Terror, when ‘some rogues slaughtered some rogues’8 as well as the religious-mystic interpretation of Napoleon’s reign, are themes shared by both his St Petersburg Dialogues and his Considérations sur la France. After 1791, Maistre came round to the view on the antecedents to the French Revolution proposed by Barruel, who argued—seconded by Maistre—that the French philosophers and the political elite had demoralized Europe, provoking a retribution by Providence that plunged France into servitude, and that the revolutionaries only served as instruments of this punishment. The struggle between ‘philosophism’ and Christianity, then the Revolution itself and Napoleon, meant further ordeals. Maistre’s later works, written after 1809, tend to constitute a condemnation of philosophers and Protestants for having intellectually paved the way for the Revolution, which he described as the work of Voltaire, Rousseau,9 Locke, and the Protestants, ‘learned barbarism, systematic atrocity, calculated corruption, and, above all, irreligiosity’.10

Written concurrently with the Dialogues, Maistre’s Quatre Chapitres sur la Russie (1811) fully concurs with the argument of Barruel by characterizing Weishaupt and the illuminati as the arch enemies of the throne and the altar.

It was not just the Voltairean rejection of Providence that drew ire from Maistre (Job 38:2, 40:2–8) but also the self-pity of the philosopher-celebrity of the day. Barely eking out a living in Saint Petersburg, deprived of his assets, library, and family, Maistre understandably considered the well-heeled, highly esteemed, but forever complaining Voltaire to be a narcissistic hypocrite.

Theodicy

Obviously harking back to Plato’s Laws,11 Maistre’s Dialogues consists of a conversation between three men after dinner, outside the city by the banks of the Neva. Both the number of the participants and the theme resonate with Plato, as the three discuss the ways of God in steering humanity by Providence (Laws 888d). In the Dialogues, Plato’s Kleinas corresponds to the Senator, the local politician; Megillus to the Spartan knight (an alien and a soldier); and the Count keeps quoting from Plato’s Laws. (In 1809, Maistre compiled notes on Laws that ran to one hundred pages; his Platonism was so blatant that Lamartine called him the ‘Plato of the Alps’.) The Count is a highly educated detractor of atheism and empiricism; the Senator a native of Saint Petersburg, a government official of Russian orthodox faith; the Knight is an émigré French aristocrat, a young man under the spell of the Enlightenment and well-versed in Voltaire. Of the three characters, the Count serves as a mouthpiece for Maistre, whose statements are qualified and softened by the Knight and the Senator. Commentators have also surmised that the author of the ‘Notes by the Editor’ is none other than Maistre himself—whose ‘dialogue’ was described by Lamartine as being more of a monologue.12

The advance of literacy was instrumental in promoting the progress of civilization and in scaling back prejudice

The genre of the Dialogues was seldom used as a form of philosophical, theological, or scholarly-scientific reflection in Maistre’s day, and has become even more of a rarity since then. After the Renaissance, the Enlightenment adopted the aphorism of lectio transit mores (‘reading makes man better’), realizing that the advance of literacy was instrumental in promoting the progress of civilization and in scaling back prejudice. Despite growing literacy, however, a streak of oral tradition had survived since at least Plato, who stated that ‘every man of worth, when dealing with matters of worth, will be far from exposing them to ill feeling and misunderstanding among men by committing them to writing’.13 In addition, Maistre relied heavily on two vital sources emphasizing the virtues of the spoken word as opposed to that put in writing. The first consisted of two freemasons, the mystic authors Louis-Claude de Saint-Martin and Jean-Baptiste Willermoz, both of whom repudiated any hopes vested in literacy. The other was the Catholic critique of Protestant bibliolatry.

Maistre held speech in higher regard than the written text because he thought that insisting on the latter inevitably led to heresy. Indeed, he blamed the intellectual confusion of the era on the mushrooming of vulgar translations and large-scale printing of the Bible, and its indiscriminate reading by the general public. The cult of the text is problematic precisely because it permits non-authoritative readings, which in turn give rise to a chaos of interpretation.14 Therefore, the propagation of ideas in print was detrimental to the unity of the church and to social peace.15 Christianity and its Bible are no exception.16

Unlike the oral tradition, the cult of books, combined with individualism, results in an infinite series of interpretations and ensuing chaos. Here, Maistre echoes the critique of Protestantism advanced by Pierre Charron in his Les Trois Vérités and by J. B. Bossuet in his Histoire des variations des Églises protestantes: Protestantism generated within Christianity a constant logomachy, a frenzy of individualistic opinion, unceasing chatter, as well as relentless, boundless chaos. Left solely to his own resources, man will inevitably get bogged down in a never-ending dispute over the correct interpretation of sacred texts. Recognizing this threat, the Christian faith presupposes the existence of a single authority that guarantees the unanimity of doctrine. The Catholic Church protected believers from devilish interpretations, but Protestantism flung the gates of hell wide open. The clamouring for a multitude of irreconcilable claims also undermined man’s trust in truth and cast all doctrine, including the Protestant faith itself, into doubt. Indeed, all doctrine will disappear the moment we refuse to recognize authority and accept only the book, without an inherent authority of interpretation: ‘Hence comes the particular character of the heresy of the seventeenth century. It is not only a religious heresy, but a civil heresy, because by freeing the people from the yoke of obedience and granting them religious sovereignty, it unleashes general pride against authority, and puts discussion in the place of obedience.’17

Maistre associated the Protestant cult of books and philosophers with individualism, which he saw as the root cause of all the problems of his age. Indeed, the imperative to break down and sacrifice the will of the individual became one of Maistre’s recurring themes.

The interpretation of the Revolution—a subject shared by Dialogues and Considérations—began to intrigue Maistre during his years in Lausanne,18 under the influence of local Catholic theologians. As its subtitle suggests, the main theme of Dialogues is the same as that of Considérations (namely how terrestrial life and government are steered by divine Providence) and it also forms a latent leitmotif in his On the State of Nature.

Running through the whole text is a description of the irreducible misery of life on earth deriving from the conditio humana. The immediate problem examined in Dialogues is why God permitted the Revolution and then Napoleon’s dictatorship to occur. The question arises because ‘there are fortunes […] that owe nothing to merit’.19 The success of the revolutionaries and Napoleon (Maistrestarted to write Dialogues in 1809) does not necessarily mean that Providence is on their side; it merely uses evil as a tool to further its own goals. The Revolution is the work of the Devil, but it is exploited by God to mete out his punishment on us. This theology of retribution had been familiar since the Old Testament: God punishes sinners through violence (Deut 28, Jer 25 and 27:6–8), but this retribution will have innocent victims as well.20 The chosen people may be the one chosen for punishment. This is the main theme of Dialogues and Considérations.

The political crimes of his age stem from the intellectual crimes of the eighteenth century

Maistre’s answer is simple. The political crimes of his age stem from the intellectual crimes of the eighteenth century, which prevented man from even attempting to address the problem of theodicy and from discerning the benefits of political association. Maistre does not wish to preserve, let alone restore, the Revolution, Napoleon, the status quo, or the status quo ante of the eighteenth century. The bloodbaths perpetrated by the Revolution and Napoleon surpassed all crimes and sins committed under the old order, and must as such be seen as instruments of retaliation in the hands of God. Not only does the existence of evil not refute the existence of God, but its manifestation as a form of punishment is evidence of Providence.

Those denying the existence of God and Providence cite human reason to claim that ‘the happiness of the wicked and the misfortune of the just is the great scandal of human reason!’21 and that ‘there is in the order we see an injustice that does not square with the justice of God’.22 This reasoning ‘comes down to: Either God could not prevent the evil that we see and lacked the kindness, or wanting to prevent them could not, and lacked the power’.23 The atheist argues that the world is unjust and this alone disproves the existence of God, who is supposed to be just by nature. In other words, the atheist, who claims to know what God would be like if he existed, actually presupposes God to refute his existence. Yet the existence of evil does not contradict the existence of God, and the world is an unjust place in the long run.

More generally speaking, the question is the central problem of theodicy: ‘Why do they just suffer? […] Why do men suffer?’24

Where do misfortune and tribulation come from? Maistre replies in Augustinian terms: ‘The Evil is on the earth. Alas, this is a truth that need not to be proved. But there is more: it is there very justly, and God could not have been its author’,25 because we merit punishment.26 Bad things happen to man because he deserves them. All this is but the way God punishes us. God may choose to punish man by fulfilling his desires, as Burke wrote referring to the revolutionaries in his Reflections: ‘They have found their punishment in their success.’27 Maistre concurs: ‘If man boldly dares to rely on himself, vengeance is all ready. He is delivered up to the inclinations of his heart and to the dreams of his imagination.’28

Maistre counters the anthropological optimism of the Enlightenment, particularly in the second dialogue, by emphasizing original sin. Evil does not come from corrupt political structures but from human nature itself. Rather than being tricks played on us by the social elite, war and other inflictions stem from the very nature of man and constitute a punishment for the flaws of that nature. The existence and tireless workings of evil on earth imply by necessity that man must be kept at bay, under the constant threat of retribution. As Augustine said, there is no just man. Maistre’s characterization of man is heavily indebted to his favourite play by Molière, The Misanthrope: ‘I regard those evils, that your soul resents, as vices consequent to human nature; my soul is not more shocked by seeing men unjust, dishonest, selfish, than by the sight of vultures hungering after carnage, or thieving monkeys or infuriated wolves.’29 And this holds increasingly true for intellectual life in the eighteenth century: ‘pride lent its ear to the serpent’.30

Should we regard the world as unjust when some of those affected by misfortune are innocent, and not all sinners are sanctioned? How can a just God permit these things?: ‘They speak only of the success of audacity, fraud, and the bad faith; they never exhaust the eternal disappointment of simple-hearted uprightness. Everything is given to intrigue, ruse, corruption, etc. […] In effect, one is sometimes tempted, on looking at the matter closely, to believe that in most cases vice has a decided advantage over uprightness. So explain this contradiction to me, I beg you.’31 [Providence] ‘sometimes appears not to perceive crimes, it only suspends its blows for adorable motives that are not very much beyond the scope of our intelligence’.32 If we could be certain of reward or punishment, we would no longer have free will or responsibility for our actions as individuals: ‘Suppose […] that in virtue of some divine law the thief’s hand should fall off the moment he committed a theft. People would refrain from theft as they refrain from putting their hands under the butcher’s cleaver. The moral order would disappear entirely. Therefore to reconcile this order […] with the laws of justice, it is necessary that virtue be recompensed and vice punished, even in this world—not always, nor immediately. It is necessary […] that the individual never be sure of anything. In fact, this is the case.’33

‘There is on the earth a universal and visible order for the temporal punishment of crimes’

Denying Providence presupposes that the punishment of sinners and the rewarding of the righteous are left entirely to the afterworld. But this is not true, for the signs of the divine administration of justice are manifest and available for study in this world of ours, sometimes more clearly than we think. The existence of both Providence and human government tell us that ‘there is on the earth a universal and visible order for the temporal punishment of crimes’.34 The true scandal would be if sin could be committed with ultimate impunity: ‘There is a great danger allowing men to believe that virtue will be recompensed and vice punished only in the other life. Unbelievers, for whom this world is everything, ask for nothing better, and the masses themselves necessarily follow the same line.’35

We cannot comprehend the world simply from the visible, from what is readily available to the senses. More precisely, the visible world merely hints at the invisible behind it.36 This assertion in itself would not be anything new under the sun. From the occultist Newton to modern scientists, everyone went by the same assumption and tried to grasp this invisible reality by uncovering it, naming it, and precisely identifying its manifestations. Yet Maistre, the advocate of the Christian tradition also says that this is also all true for the moral domain, as well as pertinent to understanding the evil afflicting humanity:

‘St Thomas said […] God is the author of evil that punishes, but not of the evil that defiles […]. God is the author of the evil that punishes, that is to say physical evil or suffering, as the sovereign is the author of punishments that are inflicted by his laws. In a remote sense, it iscertainly the sovereign himself who hangs men and breaks them on the wheel, since all authority and every legal execution derive from him. But in the direct or immediate sense, it is the thief, it is the forger, it is the assassin, etc. who are the real authors of the evil that punishes them.’37

The physical condition of the world is the consequence of man’s corruption and fall. No one in the world is immune to trouble and misfortune, regardless of individual merit. Most of man’s afflictions stem from his being man, rather than from his personal sins.

This original sin invites punishment by Providence, but human punishment is necessary as well. Unlike the proponents of the Enlightenment but like Augustine, Maistre thought of discipline as necessary, because he mistrusted education. Human life inevitably leaves room for brutality and violence, which can only be curbed by similar means: ‘There is nothing but violence in the universe, but we are spoiled by a modern philosophy that all is good, whereas evil has tainted everything, and in a very real sense, all is evil, since nothing in its place.’38 Therefore, the institution of punishment and execution is the foundation of social life.39 Society is a political construct, and whatever is political will employ coercion and violence.

‘Punishment is an active ruler, he is the true manager of human affairs, he is the dispenser of laws, and wise men call him the sponsor of all the four orders for the discharge of their several duties. Punishment governs all mankind, punishment alone preserves them, punishment wakes while their guards are asleep, the wise consider punishment as the perfection of justice. If the king were not, without indolence, to punish the guilty, the stronger would roast the weaker. The whole race of men is kept in order by punishment; for a guiltless man is very hard to find: through fear of punishment, indeed, this universe is enabled to enjoy its blessings. All classes would become corrupt, all barriers would be destroyed, there would be total confusion among them, if punishment either were not inflicted, or were inflicted unduly.’40

From Maistre to Bourdieu and Foucault, French theorists consider power a key component of society and do not recognize social relationships unaffected by power, which contract theories argue are created by the pacta unionis (with the state being nothing but the result of the subsequent pacta subjectionis).

Executive Power

Man is subject not only to Providence but, inevitably, to human penal power. As Maistre underlines elsewhere, in his Considérations, there is no society without government, and there can be no government without the power to sanction offenders. Man’s nature may not be amenable to change, but it is possible to reduce his propensity for violence, and this requires authority. Coercion by sentencing and penal enforcement, along with violence itself, were pet themes for Maistre, who was labelled as a fascist by Isaiah Berlin and his followers for precisely this reason.41 Contemporary literature, however, does not regard Maistre as either a prophet of the past or a proto-fascist.42

The direct target of Maistre must have been Condorcet, who believed that humanity had a chance for eternal peace. More generally, the eighteenth century introduced and cultivated the topos of the ‘noble savage’, of the peaceful man of tribes and nature, only corrupted by civilization.43 It was obvious to Maistre that the myth of the noble savage had gained so much ground in philosophy because it ‘has used these savages to prop up its vain and culpable declamations against the social order’.44

The spirit of the eighteenth century demolished all obstacles that had hitherto restrained the violent nature of man

The acolytes of the Enlightenment preached the end of violence while in reality sanctifying it in the name of progress, liberty, and freedom from violence. Anything was permissible to realize the promise of a Golden Age to come, but these attempts resulted in nihilism instead of a higher moral order. Ultimately, the spirit of the eighteenth century and, later, of the Revolution, demolished all obstacles that had hitherto restrained the violent nature of man. It was against this tendency that Maistre argues violence is ineradicable (notwithstanding pledges of humanity sloughing it off) and must therefore be reined in by institutions erected for this purpose. We need the executioner implementing a court verdict, just as we need soldiers, precisely to help us restrain man’s innately violent nature and to enable our peaceful coexistence on earth.

The optimism of the Enlightenment was not borne out by the Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Maistre suggests that it is not the political order that is violent and despotic but man himself, and that the most utopian dreamers appear to be the most violent of all. The paradoxical barbarity of the Enlightenment is nowhere more manifest than in the blindness of its philosophers to man’s propensity for violence, even as they seek to justify unprecedented acts of mass violence and war: 45 ‘What does it matter to me that during the frightful tyranny that has crushed France, the philosophes, trembling for their heads, have shut themselves up in a prudent silence? Since they posed maxims capable of bringing forth all these crimes, these crimes are their work, since the criminals are their disciples.’46

Contrary to the speculation of philosophers, the experience of history shows that man is a violent and blood-thirsty creature. Like Burke before him and the typical conservatives after him, Maistre refers to historic experience rather than mere speculation: ‘Every question about the nature of man must be resolved by history. The philosopher who wants to prove to us by a priori reasoning what man must be, does not merit being heard; he substitutes reasons of convenience for experience, and his own decisions for the Creator’s will.’47 Historyconstitutes an inexhaustible database for the true political thinker, offering a multitude of situations for examination, along with countless interpretations, responses, and repercussions. Given that history is one of the human spheres through which God manifests himself, ‘History is experimental politics; it is the best or rather the only good one.’48

Accordingly, the scrutiny of history and nature will produce a result diametrically opposed to Rousseau and the Encyclopaedists, namely the conclusion that a harmonious natural state has never existed. Rather than being the path of progress toward liberty and enlightenment, history is produced by man, a complex, irrational, senseless, and often fanatic being. Man is not an inherently benevolent and compassionate creature who has been poisoned by the nation or religion. The Jacobins are neither warm-hearted nor gentle, but sadistic, vengeful, and violent.

‘In the vast domain of living things, there reigns an obvious violence, a kind of prescribed rage that arms all creatures to their common doom […]. It is man himself who is charged with slaughtering man. But how can he accomplish this law, he who is moral and merciful being, who is born to love, who weeps for others as for himself?’49

Maistre argues that man is not a peaceable being, and that there is no harmony between man and nature any more than nature is in harmony with itself. War is a natural state of man that is impervious to rational explanation.

The purpose and function of political order consist in placing restrictions on man through punishment by holding perpetrators to account. This function mandates the administration of justice, which in turn presupposes the existence and recognition of authority, both of those handing down verdicts and of those implementing them.

‘This formidable prerogative of which I have just spoken results in the necessary existence of a man destined to administer the punishments adjudged by human justice to the criminals. This man is, in effect, found everywhere, without there being any means of explaining how, for reason cannot discover in human nature any motive capable of explaining this choice of profession. I believe you are too accustomed to analytic thinking, gentlemen, not to have thought often about the executioner […]. He is not a criminal, and yet no tongue would consent to say, for example, that he is virtuous, that he is an honest man, that he is admirable, etc. No moral praise seems appropriate for him, since this supposes relationship with human beings, and he has none. And yet, all greatness, all power, all subordination rest on the executioner, he is both the horror and the bond of human society. Remove this incomprehensible agent from the world, and in a moment order gives way to chaos, thrones fall, and society disappears.’50

The fourth dialogue presents the executioner as the force holding society together, the cornerstone of social life. Society is but the economy of violence and sacrifice,51 but this violence is not the Machiavellian kind deployed against political opponents as a means of holding on to power, but a violence against man, the original sinner, in the interest of protecting law and order. Violence cannot be restrained or suppressed except through violence. Society is chronically violent, because man is violent to begin with. Violence and conflict are the products of human nature, as Maistre had already observed in Considérations.52

Maistre sees violence not simply as a problem that must be kept at bay but as a phenomenon with mystical properties, in that it inspires awe and excitement—as something of which the sublime is a specific form.53

Apart from the executioner, another form of violence is war, even with its implications of voluntary sacrifice. ‘War is therefore divine in itself, since it is the law of the world.’54 For all its horrors, war does not mean that the soldier is an abominable man. On the contrary, ‘the profession of arms […] does not in the least tend to degrade, brutalize or harden those who follow it—on the contrary, it tends to improve them. The most honest man is usually the honest soldier.’55 Our esteem of soldiers is nourished by their willingness to voluntarily sacrifice their lives for one another and the society they defend. This helps us comprehend the integrative effect of war, which Maistre discusses in detail in connection with sacrifice. War and execution are obviously bad, but not because of the ill intentions of the soldiers and the executioners, just as the essence of revolution as a form of punishment cannot be divined from the intentions of the revolutionaries, patently bad as those intentions may have been. The soldier and the executioner are the two kinds of men legally authorized to kill:

‘In fact, the serviceman and the executioner occupy the two extremities of the social scale, but at quite the opposite ends suggested by this fine theory. There is nothing so noble as the first, nothing so abject as the second.’56

The position of the executioner is just as paradoxical as that of the soldier, albeit in a different way. The former executes or punishes convicted criminals and is yet a lonely man shunned by others; the latter kills honourable men and is honoured for it. The discrepancy in how we view each reveals the unreliability, even the absurdity of human judgement: ‘as for soldiers, there are never enough of them for they kill without restraint, and they always kill honest men. Of these two professional killers, the soldier and the executioner, the one is greatly honoured, and has always been honoured among the peoples that up to the present have inhabited this planet to which you have come. The other on the contrary, has just as generally been declared infamous.’57

It is the depravity of society itself that prevents man from realizing his innate goodness

According to mesmerism—a popular intellectual trend at the time that has been echoed by all radical schools of thought ever since—it is the depravity of society itself that prevents man from realizing his innate goodness. It follows that it is not sufficient to eliminate a few individuals and institutions.58 The mesmerists, especially Nicolas Bergasse, maintained that the physical state of the human body reflected the prevailing state of society. Healing could only come from violent crisis, and the nation could not be purged physically except through a revolution of customs and habits. In short, recovery required violence. This teaching was readily adopted by the émigrés,59 but not by Maistre.

What Maistre advocates is not counter-revolution but the opposite of revolution, because he does not believe in the ultimate ‘purifying’ power of revolutionary violence.60 People believe that the execution of the criminal and the voluntary sacrifice of the soldier somehow settle man’s debt to God that he has accrued by virtue of his sins, but this does not mean that violence between men could ‘purge’ society itself of its sins and flaws (as the later prophets of violence George Sorell and Lenin would have it). The question is not whether an objective is well-intentioned or noble. Power has natural limits, and when it attempts to transgress them, it will risk destroying itself. This would be contrary to the cardinal function of power, which consists in preserving itself in order to restrict and restrain man.

Precisely for this reason, putting the brakes on power is a never-ending problem and challenge for humanity. Popular sovereignty is clearly no more than an illusion: ‘the people that commands is not the people that obeys’.61 Similarly to Burke’s characterization, the sphere of the revolution is chaotic due to disobedience and at the same time despotic, because popular sovereignty is the most despotic62 of all forms of ruling society.

For his part, in the Dialogues, Maistre leans toward theocracy, which is one reason why he avoids advocating despotism. In this respect, his most radical work is Du Pape, concerned with the restriction of national sovereignties by the Pope in such a way that stops short of undermining their power altogether. No wonder that The Pope never became popular in Gallican and French legitimist circles. For Maistre, the main power of royalty is not arbitrary or absolute, although he was not a decisionist. In his Considérations, in a rather Burkean manner, he argues that governance founded on customs, tradition, and history is better respected by subjects than governance based on sheer power. Later, in The Pope, Maistre rejected the autocratic ruler model of Machiavelli and Hobbes in favour of recognizing papal authority in investiture controversies—an office vested with the power of passing judgement on monarchs. Consequently, for Maistre, man can rely for defence against tyranny not only on divine Providence but also on the institution of the papacy. Here Maistre’s reasoning runs counter to the Whig concept of history by proposing that legitimate freedom follows from the papal authority to restrain kings.63 Maistre defends the rule of law against the revolutionaries while maintaining (in opposition to the Revolution and Napoleon) the necessity of curbing secular power by divine law.

Translated by Péter Balikó Lengyel

NOTES

1 Job 38:1.

2 Charles Baudelaire, Oeuvres posthumes, Les Fleurs du Mal, Projets de préface pour une édition nouvelle, Préface (Paris, 1908), 17.

3 Joseph de Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993), 248.

4 Jules Barbey d‘Aurevilly, Les Prophètes du passé (Paris–Bruxelles, 1880); Bernard Rerdon, Liberalism and Tradition (Cambridge University Press, 1975).

5 Zev Sternhell, The Anti-Enlightenment Tradition (London–New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 60.

6 Quoted by Pierre Glaudes, ‘Joseph de Maistre, letter writer’, in C. Armenteros and R. A. Lebrun, eds, The New enfant du siècle: Joseph de Maistre as a Writer (University of St. Andrews, 2010), 54.

7 Joseph de Maistre, Considerations on France (Cambridge University Press, 1994), 105; Jean-Paul Clément, ‘Joseph de Maistre et Bonald à propos de la Contre-révolution’, in Philippe Barthelet, ed., Joseph de Maistre (Lausanne: L’Âge d’Homme, 2005), 337–345; Friedmann Pestel, ‘On Counterrevolution. Semantic Investigations of a Counterconcept’, in Contributions to the History of Concepts, 12 (Winter 2017), 50–75.

8 Quoted by François Vermale, ‘Joseph de Maistre et Robespierre’, in Annales révolutionnaires, 12/2 (Mars– Avril 1920), 117.

9 Joseph de Maistre, Against Rousseau (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996), 112.

10 Maistre, Against Rousseau, 41. See his ‘Lettre à M. le Marquis sur la fête séculaire des protestants’, in Œuvres Complètes VIII (hereafter OC).

11 Robert Triomphe, Joseph de Maistre: Étude sur la vie et sur la doctrine d’un matérialiste mystique (Geneva, 1968).

12 Alphonse de Lamartine, Cours familier de littérature, Vol. VII (1859), 413.

13 Plato, ‘The Seventh Letter’, 344c.

14 Joseph de Maistre, ‘Examen de la philosophie de Bacon’, in OC VI.

15 Joseph de Maistre, Quatre Chapitres sur la Russie, in OC VIII, 344.

16 Here Maistre repeats Bossuet’s criticism of Protestantism (Joseph de Maistre, ‘Lettre sur l’état du christianisme en Europe’, in OC VIII).

17 Maistre, ‘Lettre sur l’état du christianisme en Europe’, 65–66.

18 Vermale, ‘Joseph de Maistre et Robespierre’, 106.

19 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 191.

20 Raymond Schwagger, Must There Be Scapegoats? (New York: Crossroads 1997); Vermale, ‘Joseph de Maistre et Robespierre’; Eric A. Seibert, The Violence of Scripture: Overcoming the Old Testament’s Troubling Legacy (Fortress Press, 2012).

21 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 7.

22 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 251.

23 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 257.

24 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 14.

25 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 14.

26 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 126

27 Edmund Burke, Reflection on the Revolution in France (Cambridge: Hackett Publishing, 1987), 34.

28 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 230 (Psalms 81, 13).

29 Molière, The Misanthrope (Kansas, 1922), 8.

30 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 140. ‘Man is insatiable for power; he is infinite in his desires, and, always discontented with what he has, he loves only what he has not. People complain about the despotism of princes; they should complain about that of man. We are all born despots, from the most absolute monarch of Asia to the child who smothers a bird with his hand for the pleasure of seeing something in the world weaker than himself. There is no man who does not abuse power, and experience proves that the most abominable despots, if they come to seize the sceptre, will be precisely those who rant against despotism. But the author of nature has put limits to the abuse of power: he has willed that

it destroys itself once it exceeds its natural limits’ (Maistre, Against Rousseau, 133).

31 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 86.

32 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 85.

33 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 16–17.

34 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 21.

35 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 9.

36 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 296.

37 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 14.

38 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 268.

39 Alberto Spektorowski, ‘Maistre, Donoso Cortés, and the Legacy of Catholic Authoritarianism’, in Journal of the History of Ideas, 63/2 (April 2002), 283–302.

40 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 18.

41 Jean-Yves Pranchère, L’Autorité contre les Lumières. La philosophie de Joseph de Maistre (Droz, 2004), and ‘Joseph de Maistre’s Catholic Philosophy of Authority’, in Richard Lebrun, ed., Joseph de Maistre’s Life, Thought, and Influence: Selected Studies (McGill- Queen’s Press, 2001); Isaiah Berlin, The Crooked Timber of Humanity (Princeton University Press, 1990); Stephen Holmes, The Anatomy of Antiliberalism (Cambridge, 1993); Peter Davies, The Extreme Right in France, 1789 to the Present. From de Maistre to Le Pen (Routledge, 2002).

42 Owen Bradley, A Modern Maistre, The Social and Political Thought of Joseph de Maistre, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1999); Carolina Armenteros, ‘From Human Nature to Normal Humanity: Joseph de Maistre, Rousseau, and the Origins of Moral Statistics’, in Journal of the History of Ideas, 68/1 (January 2007) 107–130, and ‘The Historical Thought of Joseph de Maistre’, in Journal of Political Science and Sociology, 14 (2011), 17–32; Richard Lebrun, ed., Joseph de Maistre’s Life, Thought, and Influence: Selected Studies (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2001).

43 Ter Ellingson, The Myth of the Noble Savage (University of California Press, 2001).

44 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 45.

45 Douglas Hedley, ‘Enigmatic Images of an Invisible World: Sacrifice, Suffering and Theodicy in Joseph de Maistre’, in Joseph de Maistre and the Legacy of Enlightenment (Oxford, 2011), 125–146.

46 Maistre, Against Rousseau, 111.

47 Maistre, Against Rousseau, 49.

48 Quoted by Armenteros, ‘From Human Nature to Normal Humanity’, 120.

49 Maistre, Against Rousseau, 352.

50 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 18–20.

51 Michael S. Kochin, ‘How Joseph de Maistre Read Plato’s Laws’, in Polis, 19/1–2 (2002), 29–43.

52 Joseph de Maistre, Considerations on France (Cambridge University Press, 1994), 23.

53 Burke, Reflection on the Revolution in France; Rudolf Otto, The Idea of the Holy (Oxford University Press, 1997); René Girard, Violence and the Sacred(Baltimore–London: John Hopkins University Press, 1979).

54 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 218.

55 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 212.

56 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 207.

57 Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 207.

58 Marisa Linton, Choosing Terror (Oxford, 2013).

59 Karine Rance, ‘Between Enlightenment and Romanticism, a Counter-revolutionary Mesmerism?’, in Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 391/1 (2018), 177–196.

60 Cara Camcastle, More Moderate Side of Joseph de Maistre, 2005.

61 Maistre, Against Rousseau, 45.

62 John C. Murray, ‘The Political Thought of Joseph de Maistre’, in The Review of Politics, 11/1

(January 1949), 63–86.

63 Armenteros, ‘The Historical Thought of Joseph de Maistre’.