Introduction: The Western Mental Health Crisis

With so many crises going on globally, nobody is eager to deal with yet another one. Yet, the state of mental health in the West can no longer be ignored. The so-called mental health crisis is, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in dire need of effective solutions. Especially anxiety and depression have significantly increased in most of Europe and the United States, with 9.9 per cent of the European population and 36.9 per cent of the American population facing anxiety or depression symptoms. Hungary scores relatively high for European standards with a 19 per cent prevalence and fits in between the European and American position. Therefore, the Hungarian situation can be best understood in the broader Western context. The staggering and continuous increase in anxiety and depression prevalence over the last few decades has resulted in the failure to meet mental healthcare needs of its citizens. Especially the youth, with nearly half of the European and American youth being unable to satisfy their mental healthcare needs, has seen severe mental health problems. The decline in Western mental well-being is a pressing factor on the stability of Western society. Not only do less mentally stably people have a less successful personal life on average, but mental health problems also have a negative impact on the economy due to a loss in productivity. In the US alone, mental illness costs the US economy $282 billion each year, equivalent to an average economic recession. In the Hungarian situation, the impact of mental illness costs the Hungarian economy $5.5 billion each year.

Although mental health problems are a serious problem across the globe, the scale of mental health problems is unique to the West. For example, clinical depression in Western countries is 4 to 10 times more likely than in Asian countries. Yet, I would argue that Western societies are not 4 to 10 times as ‘bad’ to live in compared to non-Western societies. This begs the question what makes Western people more susceptible to mental problems than non-Western people. In previous essays, I have talked in depth about the roles that technology, loneliness and a transcendental focus play in answering this question. Yet, one additional and crucial factor underlying Western mental health challenges is the Western outlook on doubt.

The Distinctions of Doubt

Doubt is commonly defined as ‘a mental state in which our mind remains suspended between two or more contradictory propositions and is uncertain about them’. Before dealing with the problems of this definition, it is important to emphasize that doubt, contrary to fear, is not an instinct but the result of negative emotions. Thus, doubt is a by-product of or reaction to negative emotions such as fear and anger. Thus, to live in doubt is to live in an ocean of negative emotions. One does not have to be a psychologist to understand that this may negatively influence our mental well-being.

Moreover, doubt can be divided in doubt about the external world (external doubt) and doubt about the self (self-doubt). While external doubt is definitely relevant to mental well-being, it is not unique to modern Western society. External doubt rises when we believe that the outside world is either dangerous and uncertain or if we believe that it will become more dangerous and uncertain in the future. With the homogenous power of the ‘Western empires’ losing its grip on global affairs as the only super power, the expectation of a worse position for Western people compared to its past is a common reaction to a changing world order.

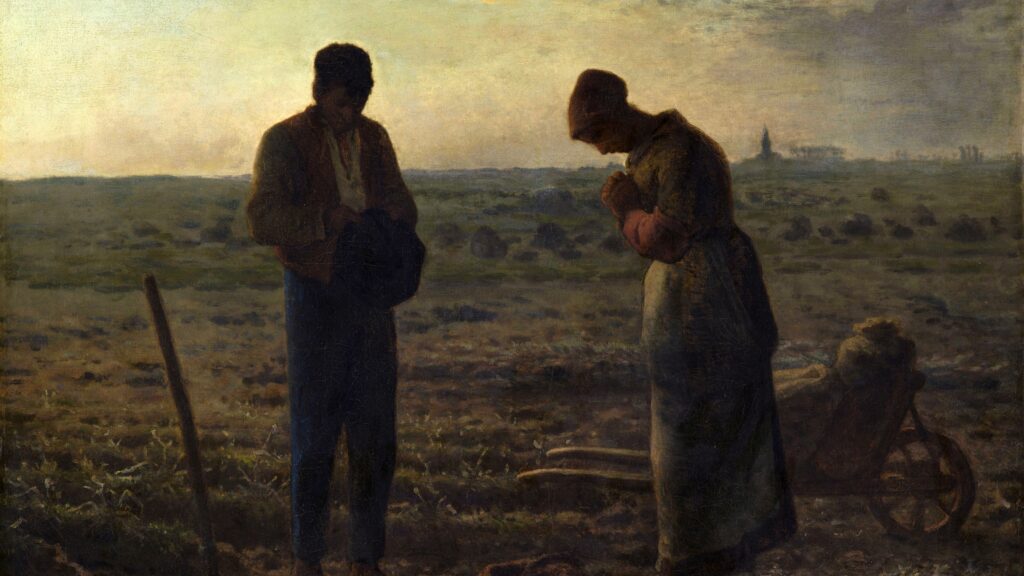

Crucially, the Western attitude towards doubt is unique in its relation to self-doubt. The Western mind with its individualistic mindset is primarily focused on individual success. To strive for individual success, compared to community-focused success, self-doubt is enhanced to ‘become the best version of yourself’ specific to your definition of individual success. The increased isolation that follows removes social solutions to deal with self-doubt. In more collectivistic and traditional societies of the past, social consensus was the antidote towards self-doubt. The underlying larger social support networks were the institutions which were cross-generational and therefore were above endless external and self-doubt or individual labels of success. In short, in moments of crisis, it provided a locus of reality to aim towards. The modern Western society is unique in the sense that it has puts the private self of the individual at the locus of reality without a supporting culture based on longstanding social wisdom. Progressive thinkers have argued that no emancipated and individualistic society is possible without breaking with longstanding social wisdom. Yet, in non-Western individualistic societies this does not seem the case. Non-Western individualistic societies such as the Pygmies in Africa or the Bhutan in the Himalayas have embedded individualism in a culture of traditional collectivistic wisdom. In the Bhutan’s example, based on Buddhist teachings and culture.

Many studies have indicated that

individualism disconnected from a culture based on social cohesion is one if not the biggest contributor to bad mental health outcomes.

This is understandable as modern individualism that emerged in Western culture is built on a modern enhancement of self-doubt. Self-doubt is known to create a positive feedback loop (creating a system which derails from the norm) which triggers and increases mental decline. Mental health problems trigger self-doubt and self-doubt increases the likelihood and severity of mental health problems. Especially with the most prevailing mental health problems, anxiety and depression, doubt plays a significant role in the rise and increased severity of the problem. Most importantly, self-doubt creates an aimlessness which increases the influence one has in changing one’s life for the better. By reducing a belief in a positive outcome and reducing motivation, one is therefore much less likely to work through their mental problems. Additionally, self-doubt increases negative thought-patterns as well as negative emotions which play a structural role in these mental problems. In short, self-doubt reduces the ability as a free agent to deal with problems and improve one’s life.

The Influence of René Descartes on the Western ‘Emancipation’ of Doubt

The negative impact of self-doubt has been known by clinical psychologists and ‘self-help gurus’ for decades at this point. Yet, somehow, they have not been able to turn the tides of the mental health crisis. The crucial insight here to understand this failure, is to understand that culture shapes the people and their minds in it. Whereas psychologists tend to focus on the individual experience and thought patterns, the cultural dispositions which shaped modern Western minds is mostly left untouched. Therefore, As Plato described in his analogy of the cave, we are blind to the true causes which can break the spell of self-doubt. Hence, to truly find a productive way to deal with self-doubt, one must understand the fundamental role that doubt plays in Western society.

One of the most influential Western thinkers on the conceptualization of doubt has been René Descartes. Descartes was an influential French philosopher who lived in the 17th century. He influenced many of the major Enlightenment and Romantic philosophers who came after him, such as Immanuel Kant, Gottfried von Leibniz and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Many of them identified with Descartes’ outlook on doubt and (sometimes implicitly) incorporated it in their own work; others took the complete opposite (and unnuanced counter-) view. Therefore, Descartes can be seen as the father of the modern approach to doubt which was internalized in Western culture.

Descartes came from a noble family and was expected to follow in the footsteps of his family as an influential leader in church or state affairs. Yet, after following education at the Jesuit school La Flèche till the age of 17, Descartes focused his attention on mathematics. Descartes was displeased with the way that medieval philosophy derived knowledge. At the time, Aristotelian syllogisms were the primary accepted mode of deriving knowledge. Syllogism use a general rule and a special rule to derive a third rule. For example: All birds fly (general rule), all pigeons are birds (special rule), therefore, all pigeons can fly (third rule). According to Descartes, syllogisms were problematic for two reasons. First of all, the general rules themselves are speculative and therefore, all knowledge derived from them is speculative as well. For Descartes, general rules that were derived from past experience or wisdom were problematic as they (1) were not derived from his own rationality and (2) because most people are unable to make a distinction between reality and falsehood and are thus unreliable. Descartes often argued this through the example of dreams. In our dreams, we are experiencing many things, but as we know, these are falsehoods. Therefore, even the general rule that we have bodies cannot be relied upon as in our dream world we also experience having a body which in fact is not ours. The second problem for Descartes arises because syllogisms do not allow for the discovery of new general rules and therefore for the discovery of new knowledge.

Therefore, Descartes, attempted to bring mathematical certainty to the realm of philosophy, all other sciences and thinking as a whole. To do so, Descartes disregarded any general rule which he had learned in his education and from society. His general attitude thereby was that anything which he did not ‘prove’ himself was therefore to be disregarded as doubtful and distracting. After long contemplation in solitude and observation on his travels, Descartes his attitude of doubt let him to arrive at his most famous general rule/axiom: Cogito, ergo sum (I think, therefore I am). According to Descartes, when I doubt my own existence, I do so by thinking about it. Therefore, the only thing that one knows for sure is that the thinking mind exists to doubt everything. Everything else, should be met with doubt as distinguishing between reality and delusions is problematic.

The Radical Impact of the Professional Doubter

It is hard to overstate the radical impact of Descartes his views. Descartes his viewpoints let to passionate proponents and opponents of his views. On the one hand, universities in the Netherlands, his home country at the time of writing most of his work, banned his work. On the other hand, proponents of his work were passionately defending his ideas throughout Europe and became ‘professional doubters’ themselves. The proponents incorporated Descartes his attitude on doubt in their own thinking and teaching. This tripled down over the centuries into general Western culture. Thus, the Western mind slowly adopted the ‘doubtful mind’.

The proponents of Descartes have argued that Descartes enabled future thinkers to question the ‘unquestionable’ general rules of society. This led to innovation, creativity and helped Western societies to prosper through the scientific revolution and industrialization. The liberal societies that emerged have indeed created wealth, prosperity and many emancipated rights to people at large in Western society. The critical thinking to which Descartes contributed, has given rise to the powerful scientific method and the success that followed. Yet, this radical cultural shift also has had its costs. Thinkers such as Jacque Ellul and Friedrich Jünger have written about some of the costs of the emergent Western technological societies (to read more on this topic, read my other essay).

Moreover, Descartes his conceptualization of doubt and the disregard for the experience and wisdom of the past has resulted in throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Even though our current society, like all societies, has its own unique problems, there also are universal problems that are true for the human experience in general. We all go through the life-cycle of life and death with many of the same challenges (e.g., how to deal with hardships, relationships between men and women, dealing with authority etc.). Therefore, there is wisdom to be found in the way that the brightest minds of the past dealt with issues which are still relevant to us today. Additionally, it is impossible to know everything. Therefore, authority and expertise are required to make sense of the world.

Thus, by removing authority altogether, man is left with no direction and nothing but doubt.

It is true that critics have rightfully so pointed out that authority can and has been corrupted and misused in the past. We are imperfect beings after all. Therefore, we should always be conscious of the corruptive nature of authority and try to correct and improve upon it wherever possible. Yet, by accepting genuine authority, we are able to take the benefits of the work of others. More importantly, it means that we are able to learn from the mistakes and reflection of our ancestors and therefore do not have to face all the same hardship they did. Life is challenging enough as it is and when we disavow the past, we are doomed to repeat it.

In his own time and the centuries that followed, Descartes first influenced the intellectual class. However, by the beginning of the 20th century and especially since the 1960’s, the attitude of (radical) doubt was internalized by the general population, especially the younger generations. By radically doubting and breaking down the authority of traditional institutions such as the family, we have seen the rise of generations that have believed that their own mind can reinvent society as a whole in a productive way. Unfortunately, the complexity of these institutions has seen rise to the derailment of such institutions (e.g., the family and community) due to the radical break with past conventions.

One of the primary underlying flaws in Descartes his thinking was that our mind is not merely rational and that many people come to different conclusions based on different rational deductions. Hence, it is not surprising that one of Descartes his primary axioms which he deduced from his cogito axiom was the existence of God. Yet, his cogito axiom and method of radical doubt led his proponents in the future centuries to scrutinize this position and give rise to reductionistic materialism. This is an important example of how the doubtful and individualistic mind can lead people with the same method to radically different conclusions. Additionally, our mind can come to one conclusion today and to another one tomorrow. Therefore, to rely merely on the rationality of one’s mind is to worship it as a false god. This is not to say that raising doubt has not also caused positive outcomes. The civil rights movement in the United States is a good example of such a positive force. Yet, this was, at least in part, also based on the sanctity of human life as it was conceptualized by Christian (inspired) thinkers in the past. Thus, the devil is in the details and as Aristotle would argue, moderation is not a virtue for nothing.

The Psychological Problems of Descartes: His Doubt Axiom

Lastly, to bring home our case against the professional doubter, one must understand the psychological misunderstanding and negative consequences of Descartes his conceptualization of radical doubt. In his famous book Discourse on the Method (1637), Descartes described his thought process and experience in how he got to his cogito axiom and radical doubt. Descartes concluded that doubt actualizes in the final analyses in a static state from which one can come to true knowledge. At face value this seems persuasive as every human being has experienced feeling doubtful. Yet, psychologically speaking, doubt is not a (static) state as Descartes describes it. The human mind works through an antagonistic coexistence between affirmation and denial. When one affirms something, one also denies the opposite simultaneously and vice versa. Thus, our mind continuously goes between affirming and denying propositions. Doubt arises during this process between these two states but is no static state itself. One cannot be in a static state of doubt as the inability to act itself also consists of an affirmation or denial. This is crucial as the modern ‘doubtful mind’, based on Descartes his abstract theorization of doubt, endlessly looks for a static doubtful state which is nowhere to be found. By doing so, the doubtful mind has to deny the existence of the two static states to sustain the belief in the cogito axiom. The doubtful mind has to internalize self-doubt as the primary mode of being to sustain this illusion. This process leaves it in a constant mode of self-doubt and distress with feelings of suspense, disappointment, uncertainty, fear and sorrow. This leaves the modern doubtful mind in a mentally vulnerable place which attributes to the staggering rise in anxiety and depression in the West.

The proponents of Descartes have often criticized the ‘normal mind’ with its lack of radical doubt to only have illusionary axioms on which he builds his life upon. This misconception exists as there are ‘undoubtful minds’ which indeed do not critically assess the worthiness of the authority of the institutions they put their trust. This is certainly the case for some, but the ‘normal mind’ does not exclude critical thinking at all. The normal mind in fact has to critically assess information to affirm or deny something. Contrary to the doubtful mind, the normal mind actively accepts the responsibility of their own thinking and the actions which follow.

Contrary, while staying in a mode of doubt, the doubtful mind has the illusion that no choice can be made. The mind is therefore free of responsibility to live with the consequences of its choice. A good modern example is the selection of one’s spouse. The doubtful mind believes that there is always a potentially better person out there. Therefore, the doubtful mind is consumed by the potentiality of bad outcomes when one commits to an imperfect person. Hence, the doubtful mind is deluded in thinking that by not committing to anyone, he can stay in a doubtful mode, waiting for the perfect person to appear. As one might understand, this ideal person is a fantasy. Thus, doubt cannot exist without clinging to a fantasy of potentiality to sustain itself. In other words, the doubtful mind mistakes denial of making a choice for a state of doubt.

To indefinitely wait for a perfect spouse who will never come (I am sorry to burst the bubble), is to deny the actuality of choosing a spouse and building a family in reality. Hence, to be a doubtful mind is to live a life looking back. Doubt arises as a retroactive reflection in which we look back on how we got to our affirmation or denial. In the case of the spouse, the doubtful mind starts to wonder if the person he came across was good enough to meet the doubtful fantasy. In conclusion, to be in a constant mode of doubt is therefore to catch a ghost, deny the responsibility of making choices while having the illusion of pure rationality.

Conclusion: A Productive Way Forward

As we conclude this essay, it is important to start having the conversation as a society why we seem unable to counteract the mental health crisis in the West. Although there are many reasons, one that is mostly left unspoken is the impact of Descartes his doubtful mind. The implicit distress, negative emotions and vulnerability for anxiety and depression which it creates is one of the crucial underlying factors which we have to culturally address.

The doubtful mind has been persuasive and embedded in modern Western culture. Therefore, it is important to understand the underlying psychological falsehood. Radical doubt only works as an abstract confusion which paralyses people into a void of distress. Additionally, doubt enhances the inability to make decisions and take responsibility for your actions. To be in a state of the doubtful mind, is to be in a state of looking back. It is to confuse the doubt of a better potential future with the denial to decide and shape one at all. In short, in a state of the doubtful mind, one doubts about everything, including doubt itself. The antidote is the realization that we need a social embeddedness connected to the shoulders of giants which we stand upon. Our mind is not purely rational, and it cannot understand or know everything there is to know. Therefore, we should aim as a society to take the responsibility to look for genuine authority in past and current generations and to heal the Western mind. To accomplish this, we must do the hard work of creating a pathway forward in which man is able to affirm and deny choices of its own destiny without creating a suspenseful void of doubt that gives rise to mental decline. I believe that with the rising awareness of mental decline in Western society, now is the time to move productively forward and re-stabilize a prosperous society based on moderation, critical thinking and responsibility.