This article was published in Vol. 3 No. 3 of our print edition.

The Establishment and Mission of the Barna Horváth Hungary Law and Liberty Circle

In one of his presidential addresses, Richard Nixon (1969–1974) pointed out that by far the most important appointments a US president makes are those to the Supreme Court of the United States. He emphasized that ‘Presidents come and go, but the Supreme Court, through its decisions, goes on forever. Because they will make decisions which will affect your lives and the lives of your children for generations to come…’ He concluded this address by pointing out that ‘there is probably no more important legacy that a President of the United States can leave in these times than his appointments to the Supreme Court’.1

But President Nixon’s address can also be understood in a more profound way, beyond the filling of vacant seats on the High Court. It integrally related to the Constitution, the rights enshrined in it, the law and, most importantly, judicial interpretation as an essential part of the intellectual and cultural dimension of American life. By emphasizing the influence of judicial decisions and legal interpretations ‘on the generations to come’, he highlighted the essential role the judiciary, legal thinking, and legal tradition play in preserving, shaping or, alternatively, changing the context in which American virtues, values, and way of life find expression.

President Nixon’s observations about the importance of the federal judiciary are reflected in the increasing stakes of judicial nominations and confirmation processes, and the unprecedented political atmosphere resulting in harsh and bitter US Senate debates.2 Many law professors and thinkers—among others Richard Bellamy, Ilya Shapiro, Jeffrey Rosen, Christopher Caldwell, and Charles Kesler—agree that a major recent focal point in American political discourse has been battles over judicial power and the federal judiciary.

One critical reason for the contentious battles over the nomination and appointment of federal judges is the seminal debate between those who believe in a ‘living’ Constitution, which evolves over time as political, economic, social, and cultural developments dictate, and the ‘originalists’, who believe the Constitution should be interpreted according to the context of its adoption and in accordance with the plain meaning of its words. This dimension of the legal system and legal culture are relevant not only in the United States, but also in other countries with a constitutional tradition. In America, the debate gave rise to the creation and growth of the Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies, Inc., a transformative law association consisting of 65,000 lawyers, law students, and law faculty members with chapters in every major law school and city.

To better understand this context, this article first aims to highlight the development and nature of judicial power in the United States, as well as in Europe. Then it considers the historical circumstances that gave rise to the idea, establishment, mission, popularity, and accomplishments of the Federalist Society during its 41-year history. The article will explain how young lawyers and law students in Europe and other countries are adopting the Federalist Society model through an International Law and Liberty Society consisting of Law and Liberty Circle law student and lawyer groups. Last, but certainly not least, it outlines the main purposes of the recently formed Hungarian Law and Liberty Circle by examining its first public events and conferences.

I. ‘The Law Is Not Only What We Have, It Is Rather Who We Are’

One does not really need to look far beyond the aftermath of the Founding Era of the United States to comprehend the important role of the judiciary and constitutional interpretation, and the disproportionate power and impact a too-expansive judiciary can have on the democratic process.

One of the major questions of the American Founding Era and the Constitutional Convention was the debate around sovereignty and the vertical distribution of power between the national government and the states. Was it to be an alliance of colonies which regarded themselves as independent states that could withdraw freely? Or was there to be one demos and people under the Constitution and thus ‘We the People of the United States’ as a whole, and not, ‘We the People of individual states’? This question, along with the differences and disagreements between Federalists and Anti-Federalists over the respective powers of the federal government and the individual states, remained open, even after the adoption and ratification of the Constitution (1787–88). The debate focused on the principle of ‘federalism’, its corresponding virtues, and, in the mind of those fearing a too-powerful national government, its dangers.

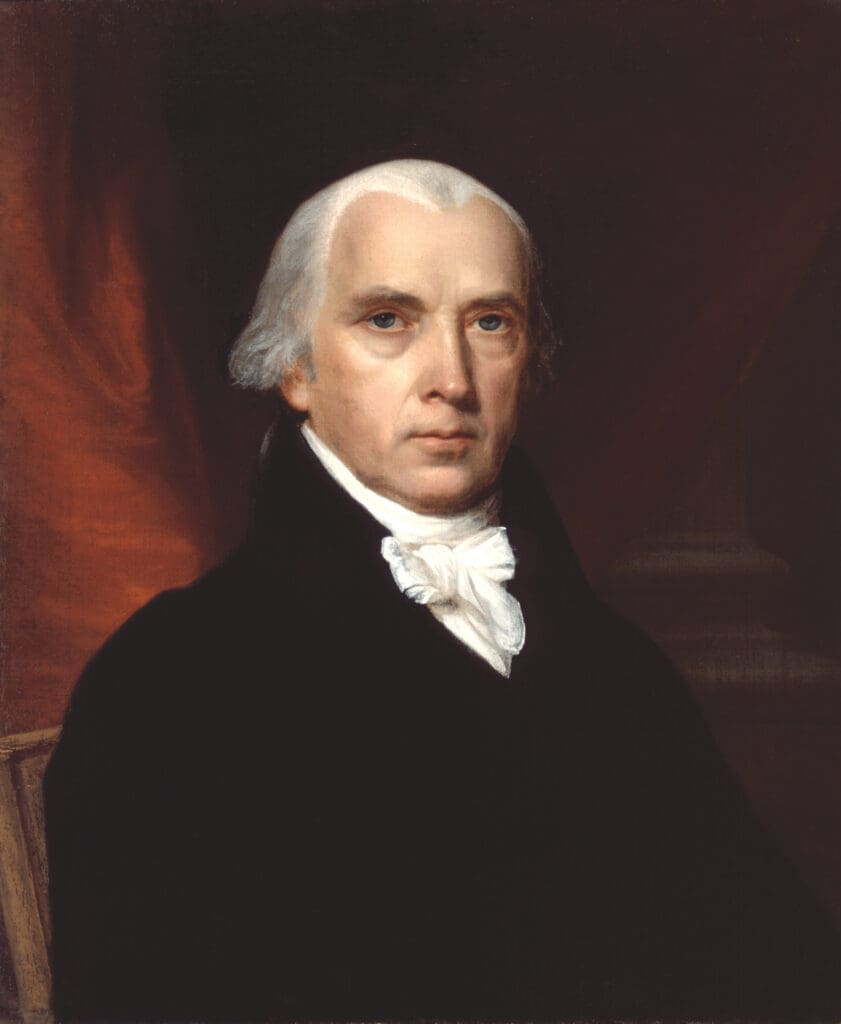

Chief Justice John Marshall (1801–1835), nominated by the Federalist President John Adams (1797–1801), was an advocate of national power.3 In his farewell address from Washington he stated: ‘In war we are one people, in making peace we are one people, and in all commercial regulations we are one and the same people.’3 Two of the few major milestone opinions the Supreme Court decided in the Marshall era had profound impacts on the question of sovereignty. Nationalism was reinforced by the decision in the Marbury v. Madison case,4 which confirmed the power of the federal judiciary to strike down unconstitutional laws. In upholding the constitutionality of the Bank of the United States, the McCulloch v. Maryland decision5 provided the federal government with ‘implied powers’, which, when necessary, could be relied upon to promote a ‘nationalist’ reading of the Constitution disfavoured by the states. At the same time, this verdict also declared the supremacy of federal law over state law.

In the ensuing period of ‘nullification crises’ (1832–1833), the US Supreme Court rejected the theory that state courts have the power to refer to the state constitution (or to the US Constitution) to set aside (or ‘nullify’) a federal regulation.6 As a result, the Court not only became the final arbiter in questions of constitutional interpretation, but also gained power to decide over the respective competencies of the federal government and state governments. This early battle over the federalist principle, won by the Federalists, set the stage for later judicial and non-judicial conflicts over the proper relationship between the national government and the states. Although ‘the United States became singular rather than plural’,7 unsettled details about the relative powers under the Constitution created open questions that are still being debated.

As the power of the US federal courts grew, the centralization of national power and the growth of progressive policies were facilitated. Although in 1791 the Anti-Federalists had secured the adoption of a Bill of Rights containing the first ten amendments to the US Constitution (which were designed to protect individual rights and state sovereignty),8 after the Civil War and the adoption of Reconstruction-era amendments, the US Supreme Court started using these rights to undermine state sovereignty. This was done through the ‘incorporation’ of these rights,9 by which means the Supreme Court claimed the power to protect individual rights from abuse or neglect at the hands of the states. In essence, these civil and political liberties became ‘nationalized’. By becoming the arbiter and protector of the Bill of Rights, federal courts diluted or undermined the constitutional and regulatory power of the individual states and the independence of their state judiciaries.

In the years following the Second World War, and especially since the 1960s, this expansive interpretation and implementation of national constitutional authority gave rise to a previously inconceivable centralization of judicial power, and transformed the theoretical, more balanced, federalist arrangement. The ‘growth from above’ of national power through federal judicial review and activism was contrary to the Founders’ ideal and their historic attempt to build a lasting federalist arrangement to promote self-government. To the concern of many, it began to distort the democratic and consensus-seeking decision-making process of the political branches, ironically placing individual rights as the defining feature of the common good.

Princeton constitutional scholar Robert P. George has explained that the ‘dominant mode of discourse’ or ‘narrative’ of the current era is the discourse of rights. Consequently, Americans have learned to pursue their desired policies or norms through the language of rights.10 As the idea of the ‘living Constitution’ and the progressive ideology became dominant, judges began to interpret the Bill of Rights to include such rights as the right to sexual and reproductive conduct and the right to exclude religion from the public square using a ‘wall of separation’ theory not contained in or contemplated by the Constitution. In essence, the ‘incorporation’ of the Bill of Rights resulted in an expansive interpretation of the Constitution that has transformed judicial power and American society beyond anything ever imagined by the Founders.

The Court’s reliance on an illusory ‘wall of separation’ isolating religion from public life is a prime example of the shifting framework of constitutional interpretation. As originally conceived, the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights was designed to allow states to freely regulate relations between religion and public life. Under the Establishment Clause, the US Congress was forbidden to pass a law regarding the establishment of a religion. The Establishment Clause was not designed to prevent states from working out their own individual arrangements for the promotion of religion for the common good. In fact, many of those promoting the Establishment Clause and its prohibition on the establishment of a national religion were, in fact, deeply religious people. The main rationale behind prohibiting Congress from establishing a religion was to preserve religion as a public common good that is an integral part of American virtues, worthy of communal support, and to protect them from government control.11

‘Law and Liberty Circles…safeguard, cherish, and transmit the respective cultural and constitutional heritage that includes a certain way of life, its virtues, and fundamental principles’

However, in its 1947 decision in Everson v. Board of Education, the US Supreme Court ‘incorporated’ the Establishment Clause and gave itself the final say on the relationship between religion and public life in every one of the forty-eight states at the time.12 In the following six decades, the Court used the Establishment Clause to justify building a ‘naked’ public square, thereby negating the Founders’ conception of religion as a positive influence on the common good.13 This resulted in the promotion of a secular American public life, in which traditional religion is relegated to the private sphere and where progressive, government-funded, non-theistic humanitarian social programmes thrive in place of traditionally religious initiatives.

This distorted interpretation of the Establishment Clause turned the traditional American view of religious freedom on its head, enabling progressives to capture constitutional interpretation as a vehicle for achieving their own ideologically driven agenda. A key feature of the ‘living Constitution’ was the ‘discovery’ by the Court of a ‘right to privacy’. The concept was used as the basis for creating a national right to abortion in the 1973 Roe v. Wade case, and later creating rights—including the right to sodomy among men (Lawrence v. Texas in 2003) and the right to same sex marriage (Obergerfell v. Hodges in 2015). In this manner, as early as the 1970s, the Court adopted a super-legislative function by using an expansive view of its power of judicial review to undermine the power of states to legislate on sensitive moral and social issues in accordance with their own political activity. Thus, it overrode state constitutional frameworks to enforce a strong view of individual autonomy according to a right-based judicial review. The law, along with the court system, has been used as a vehicle to achieve social progress, but it less and less reflected the American tradition, way of life, and virtues the law and the Constitution were originally designed to safeguard.

By the 1980s, many Americans had begun to question and resent the US Supreme Court’s abuse of its judicial review function, recognizing that the original meaning and principles of the Constitution and federalism were being ignored or lost under the Court’s expansive framework of judicial interpretation. Even though this is a uniquely American story, a similar trend can be seen within European integration. European law and its institutional arrangements have developed in a way that do not reflect, but instead increasingly transform and undermine, the traditional values and inherited traditions of their member state communities.

II. The Mission of the Federalist Society in American Constitutional and Legal Culture

In a famous quote, Harvard law professor Paul Freund stated that the US Supreme Court and the federal judiciary ‘should never be influenced by the weather of the day; but, inevitably, they will be influenced by the climate of the era’14 (emphasis added). But, what if the federal judiciary was used to create and shape the climate of the era, as if by seeding clouds to make it rain? By the 1980s, the US Supreme Court was deciding America’s most essential and divisive legal, political, social, and cultural issues, using a ‘living Constitution’ doctrine to facilitate or ensure the domination of society and culture by a liberal and progressive orthodoxy. Concerned or dissenting conservative and libertarian lawyers and law students began considering how to create a ‘level playing field’, on which both progressive and conservative views about constitutionalism, federalism, and rights could be fairly debated. If granted equal access to law schools for debating these ‘first principles’, conservatives and libertarians believed their ideas would gain traction and help restore the Founders’ vision for a constitutionally governed federal democratic republic.

President Ronald Reagan recognized this need and wanted to reach out to committed conservative lawyers, especially the few early leaders in legal academia who were sympathetic to the cause, including Herbert Wechsler, Robert Bork, and Raoul Berger. In 1982, a handful of law school students at Chicago, Harvard, and Yale universities began to notice the dominance of what they described as a ‘liberal orthodoxy’ on law school campuses, where progressives held a monopoly over access to the minds of young law students. At these prestigious law schools, some students seeking another approach to the law found a couple of key faculty members, including Robert Bork and Antonin Scalia. They each embarked on holding conferences and debates including both sides of the legal debate—a key feature of the resulting Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Students that remains to this day.15 Over the next decade, while remaining non-partisan and apolitical (not taking official positions on political or policy matters), the Federalist Society increasingly embraced the interpretative theory of Robert Bork, Raoul Berger, and Antonin Scalia, which focused on considering the original text of the Constitution as reflecting the Founders’ intent. Ironically, it was a liberal (in a progressive, not classic sense) law professor, Paul Brest, who first termed this interpretation method ‘originalism’.

By the middle of the 1980s, the Reagan administration had coalesced around originalism and Attorney General Edwin Meese embraced the Federalist Society, believing that it could provide a pool of disciplined and well-credentialled conservatives who, in public service, would follow sound, originalist jurisprudential principles. By seeking out and mentoring these young attorneys (and expert fellow mentors like Antonin Scalia), Attorney General Meese was able to facilitate the growth of ‘originalism’ as an alternative (and more legitimate) method of interpreting the Constitution. Subsequently, Antonin Scalia was appointed by President Reagan to the US Supreme Court and became the first self-identified originalist on the Court.

In the following three decades, the Federalist Society grew in numbers and reputation to become a transformative force in the American legal system, including law student chapters at every major law school and lawyer chapters in most major cities. In addition to the debates convened by these many chapters across America, each year, the Federalist Society convenes a National Lawyers Convention, at which, over three days, approximately 2,000 lawyers, law students, law faculty, and judges participate in many panel discussions on pressing or long-term legal issues—all of which include participants from the conservative, libertarian, and liberal progressive viewpoint.

Although not taking official positions on matters of law and policy, through its programming the Federalist Society provides law students and lawyers with access to originalist principles, which, if they enter public service or public-interest litigation firms, will inform their work. Central to the promotion of conservative and libertarian ideas by its members are the Federalist Society’s practice groups, which are built around substantive areas of the law in fifteen practice groups—including, for example, administrative law, civil rights, religious freedom, telecommunication law, and intellectual property law—to galvanize those who have special expertise and interest. Furthermore, there is a faculty division with an important mission to identify scholars who want to become academics, and the division tries to help them prepare for the process in order to increase intellectual diversity in American law schools.

The triumph of the Federalist Society model is reflected in the transformation of America’s legal culture from one where the ‘living Constitution’ model was dominant to one where the originalist model is on an equal (or more ascendant) level. Many judges and scholars now openly identify as originalists, and there are many judicial decisions and law review articles employing or promoting originalist techniques in interpreting the Constitution. ‘Originalism’ has become more mainstream, and in the process, it has become increasingly appealing to non-conservatives. These are watershed years for ‘originalism’ in the jurisprudence of the Supreme Court as it has become the controlling method of constitutional interpretation.16

Much to the chagrin of progressives, a more ‘conservative’ US Supreme Court—in which the majority of members adhere to the originalist method of judicial interpretation—is deciding current cases, and is also examining past precedents, in the context of a more ‘restrained’ and originalist method than the more expansive method previously used by a more liberal Court to decide cases relating to abortion,17 religious freedom,18 the limits of the administrative state,19 and affirmative action.20 In all of these cases, the Supreme Court moved away from an expansive view of individual rights (not contained in the Constitution) and embraced the original meaning of the Constitution more consistent with the Founders’ vision and intent.

In this way, ‘originalism’ has increasingly become a preferred method of constitutional interpretation in the American legal arena. By changing the interpretative environment and framework, originalism prevents the distortion of constitutional principles by judicial fiat and restores the separation of powers, forcing Congress to do its job instead of relying on the Court to legislate from the bench on the ‘hardest’ questions. Indeed, originalism and the Federalist Society are setting the ‘climate of the era’ as one that leads back to respect for America’s first principles, including respect for the rule of law, federalism, separation of powers, individual liberty, traditional values, and judicial restraint.

III. The Barna Horváth Hungary Law and Liberty Circle

Due to the manner in which the internet and other technologies have enabled the spread of ideas on a global basis—as well as to the overreach of supranational political and judicial bodies in a manner that threatens national sovereignty, to the disproportionate influence of progressive judges on national Constitutional Courts, and to public concern or outrage over abusive national policies, laws, and regulations that severely interfere with individual liberty in times of crisis and beyond—the Federalist Society’s model for promoting originalism among law students, lawyers, and academia has attracted the interest of young lawyers in Europe, Canada, Israel, Australia, and elsewhere. In many cases, the leaders of these groups contacted the Federalist Society to learn about ‘best practices’ for chapter formation, governance, and programming. Following the practice of lawyer groups in London and Paris formed ten years ago, these groups have adopted the name ‘Law and Liberty Circle’ or derivations thereof. In April 2023, the leaders of these groups, including two Federalist Society representatives, gathered outside Paris for the inaugural meeting of an independent International Law and Liberty Society (ILLS). At the conclusion of the meeting, the leaders signed an ILLS Statement of Mission and Principles, pursuant to which they agreed to promote ‘the rule of law, natural law, individual liberty, personal responsibility, limited government, separation of powers, judicial restraint, economic freedom, national sovereignty, subsidiarity, and the fundamental freedoms of freedom of conscience and religion, freedom of thought, belief, opinion, and expression, freedom of peaceful assembly, and freedom of association’.21

Even though the political, constitutional, and legal challenges and, thus, the objectives of each of the participating Law and Liberty Circles vary from country to country, one important common denominator is the need to safeguard, cherish, and transmit the respective cultural and constitutional heritage that includes a certain way of life, its virtues, and fundamental principles. It is through a sound cultural and constitutional heritage that liberty can thrive, and citizens can pursue happiness derived from responsible choices. Freedom can only spring from a tradition and cultural heritage that has the ability to distinguish between what is true and good over what is false and bad.

The author of this paper recently organized and now leads the Hungarian Law and Liberty Circle, which envisions the formation of Law and Liberty Circles in law schools and major cities throughout Hungary. The idea of launching Law and Liberty Circles in Hungary is a natural and logical development, since Hungary always thrived in those periods during which it was a sovereign nation with an independent constitutional order that promoted law and liberty and facilitated the development of a distinctive Hungarian way of life and culture. As nineteenth-century Minister of Justice Ferenc Deák once said, Hungary cannot be governed without its own constitutional arrangement and tradition.22 In this sense, law and liberty are deeply intertwined in the history of Hungarian statehood, and therefore the historical lesson of the country is that one cannot exist without the other.

The Hungarian Law and Liberty Circle is named after Barna Horváth (1896–1973), the well-respected legal philosopher whose life story, research, virtues, and resistance to communist oppression set an excellent example among Hungarian lawyers and law students committed to the very principles for which the Law and Liberty Circle stands. He served as the Dean of the Law School at the University of Szeged and was a corresponding member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. He tried to resist the intellectual and physical takeover of Soviet communism and finally fled to the United States. By choosing his name, the Hungarian Law and Liberty Circle also wanted to pay respect to the United States that provided a second home for the far too many Hungarians who had to flee from the horrors of the twentieth century.

The inaugural event of the Barna Horváth Hungary Law and Liberty Circle took place at the end of this past June in the Károlyi-Csekonics Palace in Budapest and it explored the timely question of ‘the use and misuse of constitutional engineering’, which has much relevance in Europe. In a globalized world, one of the major objectives of the student group of the Law and Liberty Circle is to help and contribute to the comparative study of different legal systems, their institutions and procedures, as well as their general approach to law. Such comparative journeys broaden students’ horizons, thus allowing them to comprehend the roots, rationales, and purposes behind different principles and solutions. However, this knowledge and understanding come with the responsibility to recognize that law is much more than an amalgamation of rules, institutions, or thick codes. Law is part of the culture of a political community. The cultural dimension of law mirrors its past, writes its present, and projects its future. Law is not only a tool, but also a reflection of a community itself. Innovation and openness to novel rules and institutions should be coupled with the courage to preserve and transmit this heritage.

An upcoming event of the Hungarian Law and Liberty circle is a unique scientific international conference co-organized with the Center for International Law of Mathias Corvinus Collegium (MCC) to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1948, the UDHR is a remarkable achievement, as it reflects a consensus among various nations with differing historical, religious, political, and cultural traditions, and presents a vision that repudiates the excesses of both individualism and collectivism.

‘In the minds of many Europeans, the ambition of those desiring a “United States of Europe” has neglected or openly challenged the legal and cultural roots, traditions, and histories of national communities and European civilization’

While respecting the aspirational objectives of the UDHR, in the last decades, there have been growing disagreements worldwide—and especially within the Western world—as to the nature and scope of the human rights it declares. The wide acceptance as well as the brief and general nature of the UDHR have enabled numerous special-interest groups to capture and abuse the moral force and prestige of the UDHR to justify a one-sided and far-reaching human-rights discourse and agenda for their own purposes. Emerging new and false claims, and a ‘living’, expansive interpretation of rights contained in the UDHR distorts the idea of basic, inalienable fundamental rights and personal responsibility. Aggravating this phenomenon is the expansion of the power of supranational bodies to the neglect of the principle of subsidiarity that protects the universality of human rights and national sovereignty in the context of laws, cultures, and traditions. The Hungarian Law and Liberty Circle international conference will assemble world-renown professors, thinkers, and scholars from nearly every legal culture to share their thoughts and experiences on the most burning challenges the human rights system faces today, and on the question of whether and how inalienable rights can be rescued.

IV. Conclusion

Nanos gigantum humeris insidentes, the twelfth-century French philosopher Bernard de Chartres’s saying has become the motto of the Barna Horváth Hungary Law and Liberty Circle. The reason that one generation can see farther than past generations is that ‘they stand on the shoulders of giants’. The motto calls for a balance between healthy ambition and intellectual humility and respect one must owe to prior communities and civilization. In the minds of many Europeans, the ambition of those desiring a ‘United States of Europe’ has neglected or openly challenged the legal and cultural roots, traditions, and histories of national communities and European civilization. In the name of ‘progress’, the institutions of modernity have attempted to sever nations from their intellectual origins, fundamental values, and organic democratic evolution.

By standing on the shoulders of the visionary Founders of the American Republic and their prescribed Constitutional order, the Federalist Society and its members have charted a path towards reclaiming the original intent of the Founders with regard to law, liberty, and limited government. It is the mission of the Barna Horváth Hungary Law and Liberty Circle to do likewise in the context of Hungary’s constitutional, legal, and cultural heritage, as well as that of Europe.

NOTES

1 ‘Address to the Nation Announcing Intention to Nominate Lewis F. Powell, Jr., and William H. Rehnquist to Be Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States’, 21 October 1971, The American Presidency Project, www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-the-nation-announcing-intention-nominate-lewis-f-powell-jr-and-william-h-rehnquist.

2 See, for example, Michael Bobelian, Battle for the Marble Palace: Abe Fortas, Earl Warren, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, and the Forging of the Modern Supreme Court (Schaffner Press, 2019).

3 Lénárd Sándor, Constitutional Journey in the United States (Budapest: MCC Press, 2021), 25.

4 Marbury v. Madison, 5 US 137 (1803), https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/5/137/#tab-opinion-1958607.

5 McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 US 4 Wheat. 316 (1819), https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/17/316/.

6 The ‘nullification crises’ started with the Worcester v. Georgia, 31 US (6 Pet.) 515 (1832), see for example: Ableman v. Booth, 62 US (21 How.) 506 (1859).

7 Sándor, Constitutional Journey in the United States, 105.

8 Mark C. Carnes and John A. Garraty, The American Nation. History of the United States (Pearson, 2012), 154.

9 One of the first ‘incorporations’ was the Gitlow v. New York, 268 US 652 (1925), https://supreme.justia. com/cases/federal/us/268/652/.

10 Sándor, Constitutional Journey in the United States, 115.

11 Sándor, Constitutional Journey in the United States, 106.

12 The United States became the Union of fifty states in 1959 with the admission of Hawaii and Alaska.

13 Everson v. Board of Education, 330 US 1 (1947), https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/330/1/.

14 ‘Paul Freund Quotes’, www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/4279296.Paul_Freund.

15 Sándor, Constitutional Journey in the United States, 224–225.

16 Lénárd Sándor, ‘The Watershed Moment of Originalism in American Constitutional Interpretation’, Hungarian Conservative, 6 (2022), www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/current/the-watershed-moment-of-originalism-in-american-constitutional-interpretation/.

17 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, No. 19-1392, 597 US (2022), www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/19-1392_6j37.pdf.

18 Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, 597 US (2022), www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/21-418_i425.pdf; Carson v. Makin, 596 US (2022), www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/20-1088_dbfi.pdf.

19 West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, 597 US (2022), www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/20-1530_n758.pdf; American Hospital Association v. Becerra, 596 US (2022), www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/20-1114_09m1.pdf.

20 Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, 600 US (2023), www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/20-1199_hgdj.pdf; its companion case: Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina, www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/20-1199_hgdj.pdf.

21 ‘One of the key challenges of our time is to transmit our constitutional and legal culture’, MCC. hu (10 May 2023, https://mcc.hu/en/article/one-of-the-key-challenges-of-our-time-is-to-transmit-our-constitutional-and-legal-culture.

22 ‘Deák Ferenc Húsvéti cikke a Pesti Naplóban, Pest, 1865. április 16.’ (Ferenc Deák’s Easter Article in Pesti Napló), Arcanum, www.arcanum.com/hu/online-kiadvanyok/Deak-deak-ferenc-munkai-8751/deak-ferenc-valogatott-politikai-irasok-es-beszedek-6973/ii-kotet-18501873-7510/x-fejezet-a-kiegyezes-megallapodas-1865-1868-7BF9/deak-ferenc-husveti-cikke-a-pesti-naploban-pest-1865-aprilis-16-7BFA/.

Related articles: