We live in a time full of chaos and uncertainties. As the Western order is shaking and is losing its legitimacy, the temptation exists to fall back to utopian ideologies. Both the left and the right have been guilty in the past of using violence and bloodshed to strive towards their romantic utopian order. As many of the Western elites are either captured by their own utopian ideology or are in a constant state of denial of the Western reality, sensible voices need to emerge to restore what’s left of Western societies and put forward an alternative anti-ideological vision to unite the West in an aim of beauty, truth and goodness. This is the challenge and adventure of our time. As the human condition in essence does not change, we are not the first generation to face a similar societal collapse. Therefore, we can use the wisdom of past generations to guide us at our time of needs.

Famous Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky warned decades before Russia got crushed under the consequences of the October revolution of the underlying falsehood of utopianism:

‘Now I ask you: what can be expected of man as a being endowed with such strange qualities? Shower him with all earthly blessings, drown him in happiness completely, over his head, so that only bubbles pop up on the surface of happiness, as on water; give him such economic satisfaction that he no longer has anything left to do at all except sleep, eat gingerbread, and worry about the non-cessation of world history––and it is here, just here, that he, this man, out of sheer ingratitude, out of sheer lampoonery, will do something nasty.’

(Notes from the Underground, 1864)

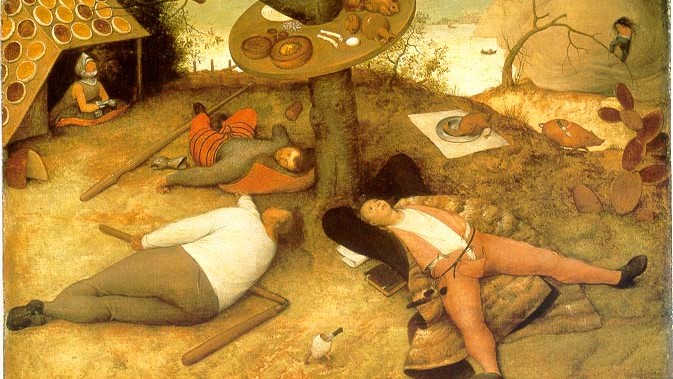

As Dostoevsky lays out, utopianism presupposes that humanity would thrive the best in a utopian dream world. None of the major utopian ideologies, Marxism, socialism, or liberalism, dare to ask what would happen if their ideology were realized to their fullest. They expect that all paradoxes and existential suffering of the human condition will disappear once their utopian society is built. Yet, as Dostoevsky masterfully puts into words, the first thing man would do if he magically arrived in a perfect world would be to tear it all down. The grand meaning of life is to be found in the adventure of overcoming hardship and challenges. To be in a world where there is nothing to strive for, is, unlike the Marxist paradigm would suggest, not the recipe for spontaneous artistic creation. It is the inception of boredom, nihilism and meaninglessness.

‘The grand meaning of life is to be found in the adventure of overcoming hardship and challenges’

Even though socialist and Marxist idealism is gaining popularity with part of the new generations, the most dominant ideology in the West since the end of World War II has been liberalism. Although liberalism has contributed to getting rid of some injustice and superstitions of the past, it has only slowed down the problem of utopianism for a while, the disruptive emancipative nature of liberalism has left the Western mind weakened and unable to face the fact that the liberal ideal is itself an abstract dream. We are now at the end of the (neo)liberal Western order, as liberalism has been unable to provide answers to modern challenges.

Once again, Dostoevsky foreshadowed the demise of the liberal utopian ideology in Demons: ‘I got entangled in my own data, and my conclusion directly contradicts the original idea I start from. Starting from unlimited freedom, I conclude with unlimited despotism. I will add, however, that apart from my solution to the social formula, there is no other.’ Dostoevsky here predicts that the liberal emancipation from the authority of the institutions that gave social stability and order to Western society leads to chaos and nihilism which is ultimately abused by those in power to produce a new kind of despotism.

The Price of Utopianism: Breaking Down Our Order

Another critical thinker who warned us from the dire consequences of abstract utopian thinking is the Irish philosopher, Edmund Burke. In his world-famous work Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) Burke went against many of his contemporaries and received tremendous backlash, as many English philosophers had at least some sympathy for the French revolution and its ideals of Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité (freedom, equality, fraternity).

Yet, Burke predicted, three years before Louis XVI saw the faith of the guillotine, that the utopian dream which in theory seemed praiseworthy would not only lead to violence, chaos and bloodshed, but that it would permanently alter the destiny of Western history. Just like Dostoevsky, Burke understood that abstract utopian dreams often, if not always, diverge from human reality which ultimately will lead to a major tragedy. Abstract human rights, which are the foundation of ideologies such as that of the French revolution and the outflowing current (neo)liberalism, are based on a falsehood. As Burke points out, abstract human rights only exist in theory. Societies do not start when people are born and consciously agree to a social contract, as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, one of the major inspirations of the French Revolution, argued. People are born into societies which go on when they perish. Therefore, human rights and freedoms are given to them by their society and can be altered only in negotiation with the environment.

‘Abstract human rights only exist in theory’

As it is evident in our technocratic model-based society, the paper-reality is far from the reality on the ground and thus, unintended consequences are plentiful. This is understandable when the vision of society is made by men of theory, instead of experience or wisdom. As Burke puts it: ‘Very plausible schemes, with very pleasing commencements, have often shameful and lamentable conclusions.’

Additionally, the realization of the utopian dream comes at a tremendous risk and should therefore be adhered to with great caution, as one needs to often destroy the fundaments that made society flourish when one tears down society to build a new one. Burke phrased it this way: ‘They have wrought underground a mine that will blow up, at one grand explosion, all examples of antiquity, all precedents, charters, and acts of parliament. They have “the rights of men”. Against these there can be no prescriptions.’ This is not to say that liberalism didn’t break down some of the oppressive and arbitrary features of pre-modern society. It just means that in doing so, it threw out the baby with the bathwater. As the human condition in its core challenges does not change, we can learn a great deal from the complex social structures and institutions that were built before us and have provided some sort of social cohesion, stability and prosperity. To reject the wisdom of what has been built over many generations in its totality is therefore to aim for self-destruction. This self-destruction often comes in the form of pride, which has not for nothing been a ‘cardinal sin’ in the Western tradition. The complexity of human society cannot be understood by reason alone. A huge price has been paid for the pride of the enlightenment philosophers to think that they could substitute the complex and historical social structures of society by one based merely on abstract reasoning. It is not that we should disregards rights and freedoms; yet experience cautions us that these rights and freedoms should be grounded in historical circumstances and concrete realities instead of philosophical doctrines.

The Uncomfortable Truth of Human Talent

Another problem of (radical) liberalism and other ideologies such as socialism and Marxism that Burke points out is its focus on equality. As George Orwell famously writes in Animal Farm: ‘All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others.’ Human beings all possess equal intrinsic value in the Judeo-Christian worldview as they are created in God’s image. Yet, they come with a variety in gifts and talents. This made Burke come to the nowadays uncomfortable conclusion that a natural order exists in which people form themselves into classes. As this undermines the liberal enterprise, the topic has been made taboo. Yet, it is undeniable that some people are healthier or more intelligent than others. Some have great talents in one area whereas others have them in another. This does not make those with a lesser health or intelligence or a lesser appreciated talent any less human or dignified. It just makes some people more successful than others, and therefore, an society equal in outcomes can only be created by force and the undermining of genius and excellence.

This by no means excuses injustice, frees us from compassion for those less fortunate than us, or legitimizes the idea that everything needs to stay the same indefinitely. As circumstances change, reform in many cases is necessary. Yet, as Burke points out, this can also be achieved gradually while keeping the essence of a nation’s traditions intact. This prevents a disruption of the continuity and social bonds that keep society together. It allows for local differences and time to adopt to reform.

‘As people lose faith in their institutions, a revolution becomes increasingly legitimized’

By contrast, liberalism also implies universalism. It makes a claim on humanity as is. Therefore, it strives for rapid changes which clash with those who guard the stability of society. This often kindles a revolutionary spirit that makes people nervous or excited, depending on their perspective. We see such revolutionary spirit in our days. The discontent, opposition and despair that is felt by several groups of society is increasingly feeding the utopian impulse. As people lose faith in their institutions, a revolution becomes increasingly legitimized by those who believe it to be the only way towards reform.

The Rise of the Mob and Oligarchical Rule

Another shadow of the modern manifestation of the Western liberal world order, is the way in which it has empowered the masses. Under the disguise of democracy, we increasingly see the rise of mob rule in the form of cancel culture, the dictatorship of the majority and the influence of oligarchies, lobby-groups and giant corporations. Burke already witnessed this in his day in the aftermath of the French Revolution: ‘I do not know under what description to class the present ruling authority in France. It affects to be a pure democracy, though I think it is in a direct train of becoming shortly a mischievous and ignoble oligarchy.’

One may be surprised how liberal democracy has derailed in oligarchy. As the new utopian elites who replaced the previous ones are merely human, their abstract principles allowed for interpretations that cemented their power and slowly but surely, they became the tyrants they once swore to combat.

‘We have to understand the importance of embedding continuation in the ruling class’

Although monarchies and aristocracies have seen their fair share of abuse and catastrophes, they were in principle more concerned with stability and continuity than the new elites, as their heirs would inherit their roles. This does not guard automatically against tyrannical rule. Burke even specifically legitimizes overthrowing tyrannical rulers, if there are no other options on the table.

This also does not mean that we have to go get rid of democracy per se. It just means that we have to understand the importance of embedding continuation in the ruling class. To maintain social order, legitimate authority needs to be guarded so that popular sovereignty cannot derail in a popularity contest, which we witness today, for example in the American elections. It means that our leaders need to be honest about the human condition as well as provide a stability in which each person, in line with their talents and destiny, can thrive. Our inability as a society to do so puts the Western tragedy on full display:

‘You would have had a protected, satisfied, laborious, and obedient people, taught to seek and to recognize the happiness that is to be found by virtue in all conditions; in which consists the true moral equality of mankind, and not in that monstrous fiction, which, by inspiring false ideas and vain expectations into men destined to travel in the obscure walk of laborious life, serves only to aggravate and embitter that real inequality, which it never can remove.’

The Last Blow: Secularism

Another uncomfortable truth which we face today is the consequence of secularism. As Burke predicted, it has led to moral relativism and societal decay. As Friedrich Nietzsche famously phrased it: ‘God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers?’

With no transcendental focus that has been able to rise to the occasion to replace the Judeo-Christian tradition in any meaningful way, it becomes time to face the music. While some, driven by a reactionary impulse, desire a renaissance of Christianity, I am sceptical of the practical viability of such a wish. Although we see some increase in religiosity among the new generations who are longing for a transcendental focus, as I previously argued, a conservative focus needs a transcendent dimension. In the Western context, the Judeo-Christian heritage may be what the doctor ordered, but I personally believe that this shift towards transcendence will most likely be a cultural rather than a purely theological one. One thing is for sure: a future of prosperity is not one of utopianism or secular nihilism. Therefore, conservatives should be confident, yet humble, about the treasure they have conserved which, with a sense of responsibility and dignity, is able to bring forth a society based on the good, true and beautiful. May the next generations, together with Burke, be able to say: ‘We are not the converts of Rousseau; we are not the disciples of Voltaire; Helvetius has made no progress amongst us. Atheists are not our preachers; madmen are not our lawgivers.’