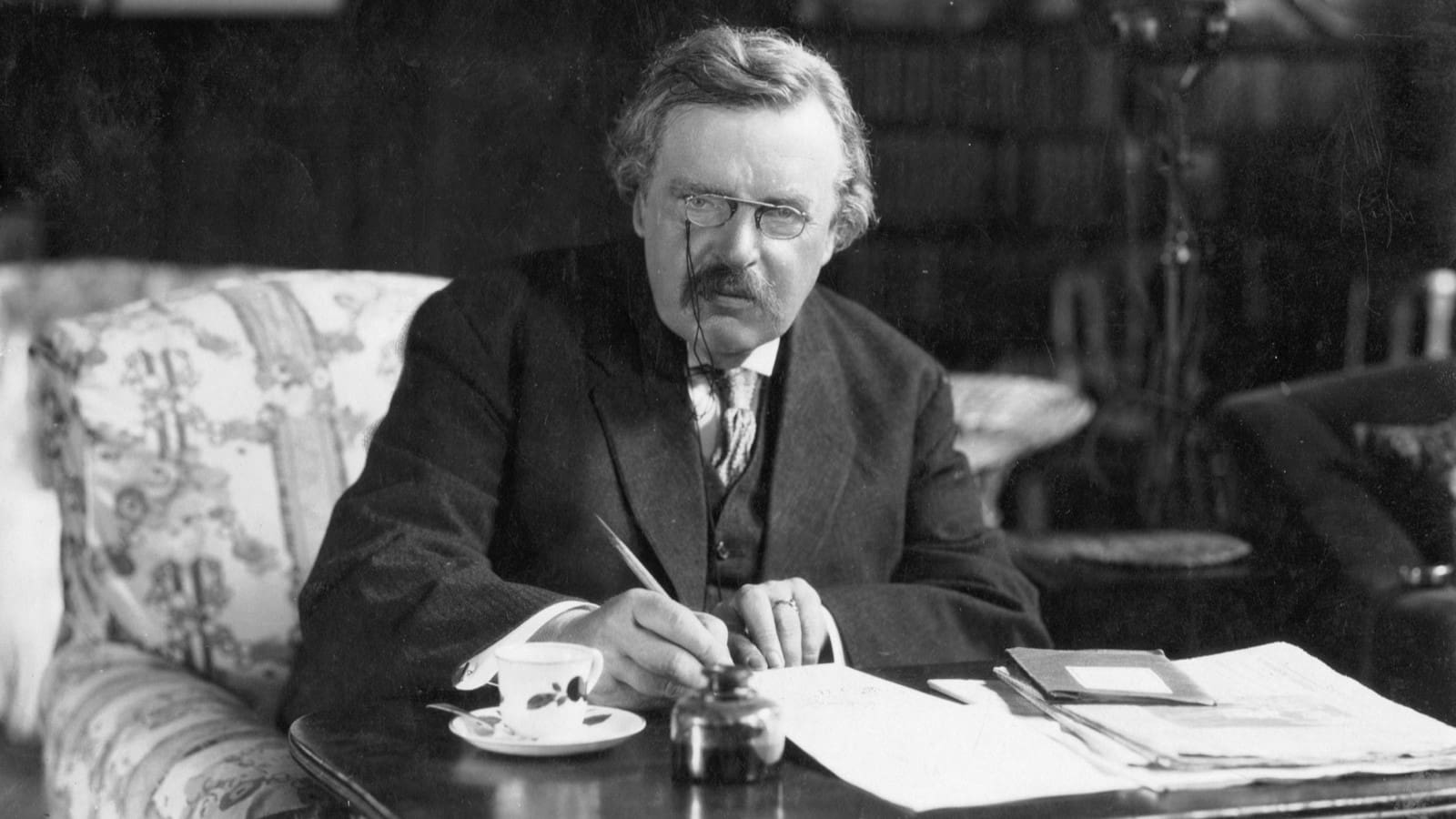

Although the majority of today’s conservatives seem to have ‘come to terms’ with capitalism, the reality is that the relationship between conservatives and ‘capitalists’ has never been easy in history. The so-called early conservative authors such as Friedrich von Gentz in Germany, then, Adam Müller and Justus Möser, de Bonald and de Maistre in France all formulated sharp criticisms of capitalism. At first glance, it might seem that the Anglo-Saxons (such as Burke) were more accepting of the idea, but this is not entirely the case. Coleridge, Wordsworth and Carlyle, and later T. S. Eliot, Catholic authors such as Hilaire Belloc and G. K. Chesterton also formulated sharp polemics against capitalism.

Belloc and Chesterton contributed significantly to the development of

the economic theory of distributism, which was based on Catholic social teaching,

especially two encyclicals: Pope Leo XIII’s ‘Rerum novarum’ (1891) and Pope Pius XI’s ‘Quadragesimo anno’ (1931). The views related to distributism, were expressed first in one of Hilaire Belloc’s best known political work, The Servile State, emphasizing that mass production will lead to the tyrannical standardization of life, collectivization and the rule of giant corporations.

In The Outline of Sanity and in other works, Gilbert Chesterton emphasized that the overall concept of ‘progress’ and the ideology of modern ‘progressivism’ are inseparable from the standards created by modern industrial capitalism. Chesterton’s anti-trust ideas, his remarks about the association of small properties, and most of all, his assertion about ‘a way out’ of the menacing perspectives created by modern industrial capitalism are still relevant today. Similarly, the notion of a better societal association that could be achieved by returning to a ‘simpler way of life’ is also still relevant, especially for conservatives, even if— in the face of the growing tendency of technocratic rationalism and the so-called ‘fourth industrial revolution’—there is little chance of its realization.

Gilbert Keith Chesterton articulated his criticism on capitalism in the most complete way in The Outline of Sanity, written in 1926. In his interpretation, capitalism does not generally mean a capitalist economy or the use of capital in the economy—in this sense, apart from the simplest societies, almost all human societies should be considered ‘capitalist’. Capitalism, Chesterton wrote, refers to an economic structure where there is a relatively narrow group with so much capital that the majority of citizens are forced to serve it for wages. Chesterton did not make any historical arguments about the development of capitalism in this sense, but states that the type of society in which England (in 1926, when the work was published) and the greater half of the world lived is defined by the capitalist economic system. Capitalism, becoming increasingly global, does not promote freedom, real ‘free competition’ or ‘prosperity for all’, the general enrichment of society and the peaceful exchange of goods around the world, but rather the expansion of the interest of big business, which Chesterton has paralleled with, among other things, the lack of real property and prostitution.

‘The true contrary of the word “property’ is the word “prostitution”. And it is not true that a human being will always sell what is sacred to that sense of self ownership, whether it be the body or the boundary. A few do it in both cases; and by doing it they always become outcasts. But it is not true that a majority must do it; and anybody who says it is, is ignorant…’[1]

In his view, it is not true that man strives for maximum profit in all circumstances and that the natural development of every society leads to modern industrial capitalism. In reality, this is exactly what ‘exactly never happens.’ The system of farms based on small estates of approximately similar size prior to modern industrial farming ‘evolved’ into the current system not because it is a natural necessity—or the ‘direction of progress.’

Rather, we should talk about the fact that by the end of the Middle Ages, the mass of smallholders (the former free peasantry) became dependent on their lords and could no longer make a living from their land: social and economic conditions, where the traditional small-tenant peasantry is strong, do not allow the development of modern capitalism. But, ‘Wherever there was the mere lord and the mere serf, they could almost instantly be turned into the mere employer and the mere employee. Wherever there has been the free man, even when he was relatively less rich and powerful, his mere memory has made complete industrial capitalism impossible. ’[2]

The most characteristic phenomenon of modern industrial capitalism in Chesterton’s assessment is the development and creation of the so-called ‘trusts,’

economic monopolies that deliberately strangle small businesses, while not infrequently operating as a criminal consortium, intertwined with political and state power. This form of monopoly is possible because, as a result of the industrialization of the world, super-rich capitalists, billionaires emerged, able to influence the state and society according to their own business interests. According to Chesterton, the means of manipulating or ‘hypnotizing’ society is, above all, advertising, which is

‘a deadly fascination into the doors of a shop as into the mouth of a snake; that the subconscious is captured and the will paralysed by repetition; that we are all made to move like mechanical dolls when a Yankee advertiser says, “Do It Now”’.[3]

Through the processes of capitalism described above, the world of the British utopian socialists (Bellamy, Wells, Webb) had already been realized by the capitalists: ‘a centralized, impersonal, and monotonous civilization’, Chesterton wrote, an accurate description of the civilization that exists today. Employees of capitalist states have exactly the same urges and characteristics that would exist in them if they were servants or slaves.

‘From the moment he wakes up to the moment he goes to sleep again, his life is run in grooves made for him by other people, and often other people he will never even know. He lives in a house that he does not own, that he did not make, that he does not want. He moves everywhere in ruts; he always goes up to his work on rails. ’[4]

What kind of solution does the author propose for the resulting situation, which does not promise a positive end in the least? First of all, his solution is the distributive state already referred to by his intellectual counterpart, Belloc. In Chesterton’s interpretation, a distributive state would be a kind of return to the system of smallholder free peasant farms. There is a need for dividing large estates, the cessation of trusts, economic-industrial-political mergers, the current banking system and for many people returning to agriculture. Chesterton emphasized that he does not intend to seduce people out of a thriving business, but suggests a resumption after an already bankrupt attempt—assessing the situation of the British economy at the time, post-WWI, in relation to a further path of capitalism that would in any case lead to economic and social collapse, while most of the people still have the will and determination to break away from the undoubted benefits of modern industrial civilization, above all, luxury, power, and convenience, and return to a ‘simpler’ way of life. Chesterton believed that the free peasant is living a ‘full life’ as he consumes products produced with his own hand or in his proximity, so much less affected by the destructive and deceptive effects of advertising and the plutocracy of advanced industrial civilizations than the so-called ‘progressive’ urban man. A free peasant, since he is no one’s employee and lives by his own land, could be less vulnerable to blackmail than a modern employee or industrial worker who is virtually at the mercy of his employer. Because the peasant’s activity is ‘non-mechanical’, and much less detached from nature, he is more creative, and less characterized by the depressive monotony, which is a hallmark of a modern metropolitan society. In Chesterton’s view, the distributive state—although the practical operation of that state is rather vaguely described—is essentially the only chance for humanity to escape the complete mechanization and complete rule of industrial and technological trusts which, like Belloc’s concepts of the servile state or slave state, would bring about the total control of the capitalist corporations over humanity.

The symbol of the distributive state is typically the arch, which could also be a beautiful symbol of medieval Christian Catholic civilization.

An architectural piece that demonstrates the theory: the many forces can balance each other and run in the same direction to hold the arch toward the sky, that is, overcome the ‘gravity’ of human nature and thus create the vertically ascending connection between heaven and earth, creating the wonderful inner spaces of a gothic cathedral.

Of course, both Belloc’s and Chesterton’s ideas have been widely criticized. Fabian George Bernard Shaw, for example, saw the distributist idea as the result of ‘Catholic credulity susceptible to fairy tales.’ A great number of critiques exist about the utopian or overly optimistic approach of the distributist theories. Supporters of capitalism still argue: while capitalism and its current state—whether we consider it ultimately negative or positive—are in line with the possibilities of man, the ideal peasant society based on smallholders envisioned by the distributist is nothing more than a romantic utopia.

If we consider the real structures and processes in today’s world, there seems to be little chance for an ’agrarian’ turn. Forced industrialization may be temporarily pushed into the background, but the technocratic rationality that underlies and serves it, the proven possibility of material power over nature, and the material benefits of exploiting nature as a resource are deeply ingrained in the mentality of the modern economy. Despite environmental protectionist movements being widespread today, considering the current level of technological development, creating an agrarian and distributist state seems a less than realistic option.

The contradictions, historical anachronisms, and other weaknesses of Chesterton’s critique of capitalism can be easily noticed, but it is worth noting that these weaknesses are more about justifying the proposed solution, and less about the critique itself. And the fact that there have indeed been periods in human history when economic functionalism may have been surpassed by a materially ‘useless’ endeavour, is no better than a symbol they so fondly use and refer to: the monumental enterprise of the construction of a Gothic cathedral. Everything else, the somewhat romanticized and idealized conception of the peasantry’s positive simplicity, or the paradigmatic nature of medieval Catholic civilization can be understood above all in conjunction with this background.

The idea of a return from modern industrial capitalism to a ‘simpler form of life’ is worth considering. It is worth considering even if it is really not very likely that modern man would want to do so, either in masses or at all, and capitalism has unquestionable benefits in addition to its drawbacks. Highly mechanized technical civilization can undoubtedly appear as development and progress, most of all, in the eyes of those who identify civilization with culture. In contrast to the ‘pre-capitalist’ economy based on agriculture brought to the fore by distributists, it seems clear that increased economic activity tends to reduce poverty. Although very few super-rich billionaires and relatively few totally impoverished people appear in the later stages of capitalism, it does not seem that a large mass of humanity would be placed in worse material conditions because of the enrichment of billionaires. In non-capitalist and non-industrialized peasant societies, there is no abundance of goods or comfort, and the raw nature of the conditions, the vulnerability to natural processes seem to be associated with underdevelopment of financial management.

It is worth adding, however, that Chesterton is obviously right about the following: the vast majority of the population of modern states does not have an autonomous economic base, with most people directly dependent on their employers as employees, with their lifestyles and living conditions, their most direct economic and social relationships primarily affected by this relationship. We also owe a number of valuable insights to distributists such as Chesterton regarding monopoly. The conditions of modern industrial capitalism realize the dominance of the economy, or the spheres directly related to it, over areas and values outside the economy. This is reflected in the efforts to continuously increase production, in the constant expansion of multinational corporations that may shape and even manage state politics. If we think of the tendencies and projections of capitalism related to Kultur in the Spenglerian sense, what we see is that in the current stage of capitalism, the technical processes related to the production and acquisition of physical objects and the related professions and activities are so appreciated that ‘culture’ is subordinated to ‘civilization.’

Modern capitalistic civilization clearly puts man’s intellectual and material activity at the service of material accumulation and the—seemingly—‘endless’ technical development. A successful businessman today has an unquestionably higher status, either in the life of society or in the eyes of his fellow man, than the traditional representatives of culture: the priest, the teacher, the writer, or the scientist in the classical sense.

All-encompassing commercialization is the general law of social coexistence,

in which economically non-convertible values are threatened with destruction. If economic processes, thanks to the evident success of a modern, highly technological economy, continue to develop to a degree and in a manner similar to what is happening currently, it will result in mechanical and technical processes taking over other areas of life. Along with technical development, in addition to the ideas that seek to rationalize it, there have been a number of recent negative trends: dystopian ideas, along with the idea of robotization, digitization, transhumanism. Without a doubt, these processes could be associated with the growing power of economic trusts mentioned by Chesterton and, before him, also by Belloc.

The negative effects of further mechanization include the fact that working with machines also makes the work process mechanical and one-sided, unlike in the traditional peasant economy, where human work was indeed more in tune with natural processes. ‘The problem is not that machines are mechanical, but that people are made mechanical’[5] as T. S. Eliot wrote in connection with Chesterton’s critique of the machine-age—and this warning should be food for thought for us in terms of the current processes and developments of world capitalism.

[1] Gilbert Keith Chesterton, The Outline of Sanity, Ihs Press, Norfolk, 48.

[2] Chesterton, The Outline of Sanity 42.

[3] Chesterton, The Outline of Sanity 96.

[4] Chesterton, The Outline of Sanity 86.

[5] Gergely Egedy, A „józan ész konzervativizmusa.” Gilbert Keith Chesterton. Vigilia 2004/6, 424-430. 427.