This article was published in Vol. 4 No. 2 of our print edition.

In recent years, realism has enjoyed a resurgence of popularity in the fora of public life, predominantly as a school of foreign policy and geopolitics. The most frequently cited intellectual and theoretical foundations of this form of realism include Thucydides (The Peloponnesian War), Niccolò Machiavelli (ThePrince), and Thomas Hobbes (Leviathan). Underpinning the school of foreign policy realism itself, meanwhile, there are of course contemporary authors such as Hans Morgenthau, Henry Kissinger (who died in November 2023), and John Mearsheimer.1 The best-known Hungarian representative of realist political philosophy is András Lánczi.2 In this context, the right-wing-conservative acceptance of the existence of interests and power relations, and the unavoidability of the struggle they give rise to, often comes up against liberal moralism. However, this raises the question of the right’s relationship to morality, if only because the right wing inherently considers itself the custodian and protector of human morality, in contrast to the amoral left (which could perhaps more precisely be defined as representing an alternative morality). Furthermore, a complete refusal to consider moral matters, on the grounds that morality—especially political morality—does not exist, but only power relations, interests, and the resulting conflicts, often leads to cynicism.

In opposition to this, there is a realist school that does not reject morality. It does not start from the contention that there are only interests and power relations. However, this Christian realism does not adopt the Kantian morality of the Enlightenment, nor conflate the Kantian spirit with Christian morality. (That is, if a specifically Christian morality exists at all; according to the Catholic philosopher Rémi Brague, for example, it does not.)3 Regarding natural law, there are also different positions within Christianity, most of which can easily be aligned with Christian realism. However, it must be noted that if there is a law of nature, then humankind observes it only partially, and we have the capacity to irrevocably go against even our own natures (see contemporary gender issues, for instance). However, the Christian doctrine of natural law is not the same as the Enlightenment perspective.4 On the other side, meanwhile, there are the Christian idealists—a movement that has grown much stronger since the 1960s. According to idealists, such as Jean Jacques Rousseau, society corrupts man, whereas according to realists, such as St Augustine, the imperfect man creates an imperfect society. It is not for nothing that Rousseau’s Confessions is the inverse of Augustine’s Confessions.5 Idealists—whether Christian or not—believe in the possibility of creating a (more) perfect world, and of eliminating hierarchies of power. Christian idealists have a hard time dealing with the existence of power, and typically also embrace a significant number of progressive goals.

This also shows that Christian realists disagree with the idealists primarily with regard to human nature, and with secular realists on moral grounds. Nor can they accept either Rousseau’s or Hobbes’s ‘state of nature’ (these are diametrically opposed concepts: one optimistic and the other pessimistic), because both are fictions. Nor is it obliged to accept the notion of the ‘social contract’, since such a contract would require a pre-existing community.6 From a Christian perspective, we could consider the Garden of Eden as a state of nature, but this cannot be the starting point for our political philosophy, since we were expelled from it after the Fall, so instead of states of nature, the true state of mankind—our fallible nature—should be taken as the starting point. My current line of thought attempts to focus on Christian realism primarily by putting it into dialogue with these two contrasting schools of thought. Of course, Christian realism is also opposed to secular idealism, but in that debate there is little common basis for dialogue, despite the fact that in the first half of the twentieth century ‘Christian realism was a practical, flexible and ethical answer to the liberal idealism of the day’.7 By the same token, one cannot simply omit Thucydides, Machiavelli, and Hobbes, all authors from whom a great deal can be learned. Indeed, frankly, I see more opportunities in a dialogue with their form of realism than in a potential discourse with Christian idealists.

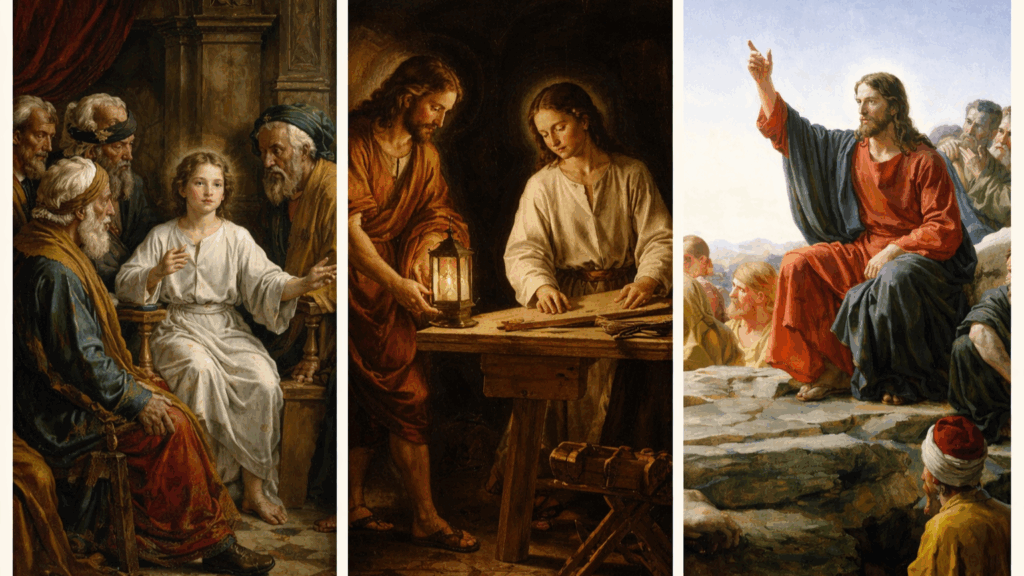

But who are the foremost authors of Christian realism? St Augustine, St Thomas Aquinas, Jean Bodin, Joseph de Maistre, Juan Donoso Cortés, T. S. Eliot, Reinhold Niebuhr, and, to mention one contemporary Anglican priest, Nigel Biggar. With their help, it is possible to outline a Christian realism that is acceptable to most denominations of traditional Christianity. St Augustine is, after all, common ground, accepted by most Christian denominations and by political conservatism. It is customary to argue against authors of bygone eras by saying that they are irrelevant in the context of today’s problems, but since human nature is universal and unchanging, their ‘context dependence’ is not absolute, and they can indeed be relevant to our present moment.8 In the following, relying predominantly on these authors, I sketch an outline of Christian realism, focusing on its image of man. I discuss its relationship with morality and moralization, Christian universalism, and particularities, especially the nation, together with the possible perception of the relationship between the community and the individual, as well as the question of coercion, especially war, participation in democracy, and finally what—Christian-realist—expectations we may hold Christian politicians to.

Anthropological Pessimism

We may concur with Reinhold Niebuhr: the world has not at all turned out the way Enlightenment optimists of the eighteenth century imagined. They were convinced that if people focused on perfecting themselves and their societies in this world instead of placing their hopes in an afterlife, all problems would be resolved.9 Niebuhr’s famous book, Moral Man and Immoral Society, inveighed against precisely such rationalist–scientific– psychological concepts: individuals, and perhaps even small communities, may be able to perfect themselves, but, due to the laws of large numbers and great interests, societies of any larger scale will never escape the problems arising from human frailty, imperfection, and sinfulness; in short, self and group interests usually overcome other moral considerations.10

‘Christian realism is not unprincipled power politics or mere pragmatism, but the intelligent use of power and politics’

Christian realism is based on anthropological pessimism. This does not mean, however, that there is no such thing as morality. On the contrary! According to anthropological pessimism, man is an imperfect being, beset by moral and intellectual limitations. According to Niebuhr, the basis of all political realism is that the radical freedom that enables human creativity also makes us potentially destructive and dangerous—that is, our dignity and our misery arise from the same source.11 Anthropological pessimism is closer than anthropological optimism to the image of man in the modern natural sciences, which is typical of the social sciences. It is precisely the division between the two that lies at the bottom of the modern political divide. To put it in simple terms, the right claims anthropological pessimism (or more precisely, realism), and the left claims anthropological optimism.12 The term ‘realism’ suggests that this approach starts from the real, not the imagined. From this, it follows that it is vital to establish how things really happen in practice, and what humans are really like (Machiavelli is usually cited as a classic example of this endeavour). However, this does not mean that what exists must also be universally accepted as normative. Thus, David Hume was wrong to see an unbridgeable gap between an ‘is’ and an ‘ought’.

Niebuhr states in his essay on the political realism of St Augustine that ‘realism becomes morally cynical or nihilistic when it assumes that the universal characteristic in human behavior must also be regarded as normative’. He then adds: ‘The Biblical account of human behavior, upon which Augustine bases his thought, can escape both illusion and cynicism because it recognizes that the corruption of the human freedom may make a behaviour pattern universal without making it normative. Good and evil are not determined by some fixed structure of human existence.’13 That is, the Christian realist has both principles and ideals, but knows what and how much can be expected from people.

The starting point of Christian (political) realism is therefore the biblical understanding of human nature and the historical experience of human behaviour. As we have seen, the realists’ image of man is usually described as pessimistic. At the same time, we must point out that Christianity emphasizes the good inherent in man, and the pursuit of that good. After all, we are God’s creatures, so we cannot be inherently bad.14 There are authors (Hobbes, but also the Catholics Joseph de Maistre and Donoso Cortés) who present man as hopelessly wicked.15 This was probably based on the experience of the conflicts of their own time (the English Civil War, the French Revolution, and the Napoleonic Wars respectively).

However, Christian realism, which takes the divine creation and its inherent goodness seriously, must also recognize the good inherent in man, and the good news (evangelion) contained in the divine revelation, and therefore strive to embody New Testament evangelical hope. In other words, compared to the absolute pessimists, Christian realists do not emphasize humanity’s inherent wickedness, but rather its fallibility, that is, its intermediate character: humans possess, generally speaking, the desire to do good, but it is diffuse and unfocused. At the same time, Christian realism does not oblige us to stick to an overly schematic picture of human nature; there can be legitimate differences between various internal impulses. It is important to be clear, however, that Christian realists cannot be principled misanthropes; we can love people more easily precisely because our expectations are more moderate than those of the idealist, who will always be disappointed in the end. In fact, for instance, as Eric D. Patterson notes, the Christian realist is not pessimistic, but simply accepts the biblical teaching of sin and the Fall.16 Niebuhr himself, who was often accused of having a ‘dark’, vaguely apocalyptic tone, rejected the label of pessimist, or even cynic, and declared himself ‘realistically optimistic’, while Nigel Biggar, concurring, states that as a Christian he stands ‘uneasily between pessimism and optimism.’17

The Moral–Political Dimension

We are well aware of the Augustinian parables of the city of God and the city of man. According to St Augustine, the two cities are present on Earth in combination, meaning that we live in what he called a civitas mixta.18 However, we must see, as Niebuhr also highlights, that this civitas mixta does not simply result from the coexistence of the citizens of the two cities, since we ourselves are civitas mixtas, i.e. the two cities are also combined in each individual.19 The image of man and society Christian realism presents is well illustrated by the biblical parable of the mixing of the wheat and the tares (Matthew 13:24–30). The tares are ineradicably present in the world, and in us, but this does not mean that there is no wheat.

Christian realism is an attitude arising from Christian faith and conviction, as well as historical experience, and is a guide to political action. In addition to their Christian convictions, Christian realists keep two more fundamental points in mind: firstly, that one’s own ideals can only be partially realized; and secondly, that the world is plural, meaning that others have different ideals. Christian realism does not merely say that the ideals of progressives are beautiful but unrealizable, but states that Christian ideals are in fact in total opposition to the ideals of progressives. Christian realism thus has a good chance of avoiding naivety: after all, Jesus did not call on us to be naive, but to be as clever as serpents: ‘Behold, I send you forth as sheep in the midst of wolves: be ye therefore wise as serpents, and harmless as doves’ (Matthew 10:16).

Realism is often contrasted with morality. But is not the Christian calling moral? It is a question of what we mean by morality. Niebuhr points out that since we cannot know internal motives, instead of inquiring into another’s internal moral convictions, it is better to judge the goodness of a political action or policy based on its external results.20 In addition, we might add, ethics is well aware of the principle of double effect, whereby intention is important, and a moral action is justifiable, even if it has negative side effects. Both views avoid passing judgement on the justifiability of a political action based on one-dimensional moral absolutes.

But we can go further, because Niebuhr also explains that although the ultimate goal of politics is the public good, we will always be pragmatic and utilitarian in practice when it comes to specifics, and always measure the specific so pragmatically that it is more a political than a moral question. The world of politics is a grey zone between ethics and technical feasibility. A political move, if it ultimately leads to a good outcome in moral terms, cannot be inherently bad, though of course, it cannot be inherently good either. A good intention is only good in principle, but the question of whether someone chooses the right means to realize their good intention is also vital, and this is something best learned through experience. Reflective morality is needed, and there are no absolute principles, (not even the right to life) which are valid in every case.21

Communality

We also suspect idealists of a kind of false universalism. What is the relationship between Christian realism and universalism? Christianity is, after all, a universal faith, with which it is not possible to reconcile all existing traditions and local practices. I think that the solution lies, first in an acceptance by the prudent Christian that the universality of Christianity is a discipline to be practiced; that is, one accepts the world, in all its diversity, as the field of action. The second point is that the spiritual realm is truly spiritual, not material. That is, Christian religious universalism lacks an obligate political component.

In any case, homogenizing liberal globalism and the universality of Christianity are not the same thing. When it comes to the human environment, Christianity is localist, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that it can accept many solutions. Moreover, despite all the talk about tolerance and diversity, at the heart of liberal globalism is the desire to extirpate all distinctions between individual people and humanity because that is how it seeks to bring about perfect equality and freedom. That is, it considers unjustifiably exclusionary all subdivisions below the totality of humanity, especially the nation, but also other levels (communities, families); everything, in other words, Edmund Burke called the ‘little platoons’ of communal life.

Christianity, by contrast, believes that humans, as social beings, can find fulfilment on this earth in various communities. Whereas the liberal globalists consider it unjustifiable to give preference to one person over another, as far as our love and care is concerned, according to Christianity, love has an order, stemming from both divine decree and our psychological limitations, as well as our spiritual needs. This ordo caritatis moves outward, from the directly given, according to which our primary obligations bind us to our spouse and our close family, then to our wider family and our small communities. As we move towards the outside of this circle, our obligations steadily diminish. If our resources are scarce, we must give priority to those who are our direct responsibility.22 Society is a community of communities, not a collection of individuals.

And here I turn to Nigel Biggar, who, as a ‘Barthian Thomist’ (that is, a follower both of one of the most important Protestant theologians of the twentieth century, Karl Barth, and of one of the greatest thinkers of the Middle Ages and the history of universal philosophy, St Thomas Aquinas), and as a Christian realist, undertakes to supply a Christian justification of the nation.23 Biggar points out that according to the Christian conception of creation, we are embodied beings, meaning that we are beset by serious physical and mental limitations. Our responsibility is not divine, but creaturely, since (and so) our resources are finite. As such, we cannot be of equal benefit to everyone in the whole world, and in fact, there are those to whom our duties are stronger. In addition to our local communities, there is also the larger polity, within which we speak the same language, share the same culture, and hold citizenship. In Biggar’s words, ‘notwithstanding the fact that all human beings are equal in certain basic respects, no matter what their native land, we might still be obliged—depending on the circumstances—to benefit near neighbours before or instead of distant ones.’24 We owe a lot to our immediate communities, and so bear a proportionate responsibility towards them. As such, it is natural that individuals feel a particular loyalty and attachment to these communities, institutions, and customs.

Due to the Christian character of Christian realism, the nation and national sovereignty cannot be absolutized—they cannot, in other words, become a secular religion replacing Christianity. However, as Biggar writes, they do provide a suitable framework within which to attain human fulfilment, and so must be supported. He puts it precisely that ‘the creaturely quality of the human condition also implies that a diversity of communities, including nations, is a natural necessity that is also good’.25 It follows from this, Biggar points out, that interests are not necessarily opposed to values. This is because Christians, precisely on account of our creaturely nature, consider correct self-love to be a virtue, from which it follows that promoting our own wellbeing and the wellbeing of our people—albeit of course not absolutely or exclusively—is the right thing to do. We can also call this the national interest.

Pluralism and Common Sense

Christian realism—mindful of Christianity’s commitment to truth based on divine revelation—does not recognize the equality of religions and cultures. Quoting the statement of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith: ‘the right to freedom of conscience and, in a special way, to religious freedom, taught in the Declaration Dignitatis humanae of the Second Vatican Council, is based on the ontological dignity of the human person and not on a non-existent equality among religions or cultural systems of human creation.’26

Christianity values the individual as a unique and irreplaceable being created in the image of God, and is aware that modern individualism can even be seen as an exaggeration of this. Christianity places great emphasis on free will and defends it in the challenging modern environment against the deterministic sciences, which challenge it.27 It does so for no other reason than because if there is no free will, then we cannot freely decide for God. Christianity, and thus Christian political realism, cannot dissolve the individual into the whole, and does not consider the individual merely a product of society, as do the Hegelians and some traditionalists on the one hand, and postmodernists on the other. Free will, in spite of all natural laws and social regulations, makes people unpredictable in both good and bad ways. In addition, since both the community and the irreplaceable individual are important to Christians, neither can be absolutized at the expense of the other. We do not seek to dissolve the individual in the community, nor to liquidate the community in favour of the individual. It should be noted, however, that there is no universally applicable, detailed set of guidelines, and we must accept that in borderline cases there will always be friction between the individual and the community. In other words, we must accept that conflicts between them cannot be eliminated, and nor can conflicts between different communities. History is a series of conflicts.

The history of ideas considers St Augustine’s Confessions to be one of the earliest manifestations of individual personality; according to this, among the Christian thinkers, ‘Saint Augustine was the first to emphasize that man is not only a thinking being, but also a person capable of loving, deciding, and acting.’28 Niebuhr likewise notes that St Augustine, in contrast to the ‘classical rationalism’ of the ancients, saw the uniqueness of man not only in reason—the ability to think, and reason—but also in other psychological aspects.29 At the same time, Christianity, following in the footsteps of the ancient Greeks and the Aristotelian Saint Thomas Aquinas, does not devalue reason, but does not absolutize it either. Thus, Christian realism cannot be irrationalist on account of its Christianity. At the same time, it also rejects the exaggerated rationalism of the Enlightenment. The human mind is limited, and requires the aid of experience, authorities, tradition, and divine revelation. But this by no means devalues the importance of common sense!30 Thus, Christian realists emphasize the importance of practices and beliefs handed down by tradition and custom, but do not dismiss the possibility of rational and logical justifications for their beliefs and convictions—they are simply aware of how few will ever be interested in them.

Christian Government

Neither freedom of conscience nor authority of the community is absolute. Niebuhr warns that neither individual freedom, nor the community, nor the state can be declared absolute because it is none of these, but rather the creator, God, that is absolute.31 On the other hand, the coercion exercised by the legitimate leadership of the political community (through institutions of state coercion and judicial enforcement), which de Maistre depicts so metaphorically by describing the executioner’s work,32 cannot be entirely excluded from the civitas mixta. Coercion means violence. According to St Augustine, from the position of governance, Christians can legitimately protect the peace and punish evil through the use of coercion.33

War is an extreme but nonetheless very common form of violence. Christian realism cannot be pacifist, i.e. it must take into account the realistic possibility of war. The theoretical basis for this is the theory of the ‘just war’, of which St Augustine was the first influential theoretician, in his De Civitas Dei, and which has recently also been defended in classic Christian terms by H. David Baer and Biggar, among others, against the Christian pacifists and the exponents of the modern, liberal version of the just war theory.34 (It should be noted that Niebuhr likewise found the just war theory excessively legalistic and idealistic.)

From the point of view of Christian realism, there is no ‘true’ form of government and social organization. Most forms of government and organization in history have been to some degree acceptable, but of course there are some (especially modern forms of totalitarianism) that are not.35 Christianity’s minimum demand in the political sphere is formulated by St Augustine: to establish and maintain peace and leave its followers alone.36 The maximalist form, meanwhile, is embodied in the Christian Middle Ages. Domestic political realism is usually identified with a strong state that effectively curtails mankind’s worst impulses (absolutism, in the case of Bodin and Hobbes, and, for Donoso Cortés, dictatorship), but since leaders are not exempt from fallen human nature, it is straightforward on this basis to advocate for a limited state and the division of power, as we see in Niebuhr, who defended democracy for this very reason.37 Christian realists can adopt a range of political positions, from the radical right to the centrist left, and their economic views can be equally flexible, ranging from support for the free market to corporatism. At the same time, their social policy must be characterized by social conservatism (conservatism of values instead of status quo conservatism). Interestingly, Niebuhr simultaneously castigated communist and laissez-faire approaches, and esteemed Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal as a fine compromise.38

Political Augustinism

Conservatism—whether philosophical or political—is not the same thing as either the Christian religion or political realism, but since it can also be considered a modern, secular version of St Augustine’s approach, since its image of man is similar to that of the great church father, there is a significant overlap between them, and they are certainly not opposites.39 At the same time, Christians must accept that since the representatives of various worldviews and positions have so far failed to convince each other by careful argument, and this is no realistic prospect of them doing so in the future, they will not be able to assert their position without political mobilization (campaigning) and engaging in the power struggle. In other words, modern democratic competition and parliamentary pluralism entail a necessary struggle for power into which Christians must enter. They cannot, as it were, remain morally pure and aloof.

I think that among Christian idealists today, it is fashionable to believe that the struggle for power is an ugly thing, and that the enforcement of Christian principles is somehow un-Christian (perhaps because it entails the coercion of non-Christians). On the other hand, for Christians, it would be mere self-harm to stay out of democratic public life and renounce all power. Catholics are obliged to engage in political life by Vatican resolutions. Christians also have the right to democratic representation of their views and lifestyles, including in the struggle for power. Once in government, they have the democratic authority to transpose their understanding into the practice of the political community through political action, so that their preferences are manifested in political decisions—in laws, financial decisions, and mediated norms.

Another question is whether prudent, careful, and smart Christian politicians in democracies should calculate how far their legitimacy extends; that is, what they can and cannot do within the bounds of popular opinion. It is customary at this point to enquire into the Christianity of today’s Hungarian government, and ask why, if the government is indeed Christian, it does not ban abortion? I can cite the example of the former Catholic prime minister of Australia, Tony Abbott, who was also faced with reconciling his own perception of abortion with that of the majority in his society. He did what he could within the constraints of political action, for example by not allowing abortion laws to be liberalized, but did not make them stricter either because taking the long-term view, he realized that this would require an enormous outlay of political capital that could be spent on enacting many other policies and that by bringing in a law sharply at variance from the majority view, he might lose support, risking defeat at the next election, thus resulting in a loss of influence for the Christian-conservative position not just with regard to abortion, but all other matters as well [as happened in Poland, partly as a medium-term consequence of PiS’s previous tightening of abortion laws prior to the last Polish elections: Ed.].40 In short, therefore, Christian politicians should not be discredited if they do not try to implement the entire Christian programme, but do only as much as current political constraints allow. Christian politics and Christian governance are not the politics and governance of the perfect, but of imperfect sinners, which necessarily entails human frailty, error, and fragmentation. Christian politics is not Christian because it is perfect, but the frailty of Christians should not be confused with hypocrisy and pseudo-Christianity.

Christian realism is not unprincipled power politics or mere pragmatism, but the intelligent use of power and politics for the sake of representing Christian ideas and the common good (bonum commune), within the bounds of worldly political constraints. However, the realization of ideals, ideas, principles, and the common good is not only limited by constraints; in the case of Christian realism, pragmatism must also be limited by Christian principles. Christian realists accept imperfection and conflicts, but not with hopeless resignation, since their two starting points are fallible humanity and Christian hope.

Translated by Thomas Sneddon

Originally published in Hungarian in Kommentár, 1 (2024), 27–38.

NOTES

1 John J. Mearsheimer, The Great Delusion: Liberal Dreams and International Realities (Yale University Press, 2018). See also: Scott Burchill, Andrew Linklater, and Richard Devetak, Theories of International Relations (Macmillan Education, 2013).

2 András Lánczi, Political Realism and Wisdom (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

3 Rémi Brague, Curing Mad Truths. Medieval Wisdom for the Modern Age (University of Notre Dame Press, 2019), 78–79, 85.

4 Nigel Biggar, What’s Wrong with Rights? (Oxford University Press, 2020).

5 Cf: Ann Hartle, The Modern Self in Rousseau’s Confessions: A Reply to St. Augustine (University of Notre Dame Press, 1983).

6 Roger Scruton, The Meaning of Conservatism (St. Augustine’s Press, 2002). See also: Joseph de Maistre, Considerations on France (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

7 Eric D. Patterson, Christianity and Power Politics Today (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 6.

8 Cf. János Frivaldszky, A házasság és a család: elnyomó hatalmi viszonyok, avagy a jog relacionális jellegének prototípusai? (Marriage and the Family: Oppressive Power Relations, or Prototypes of the Relational Nature of Law?) (Iustum Aequum Salutare, 2008).

9 Reinhold Niebuhr, Christian Realism and Political Problems (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1953), 5.

10 Reinhold Niebuhr, Moral Men and Immoral Society: A Study in Ethics and Politics [1932] (Muriwai Books, 2017).

11 Niebuhr, Christian Realism and Political Problems, 101.

12 Steven Pinker, The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature (Viking, 2002); and Thomas Sowell, A Conflict of Visions: Ideological Origins of Political Struggles (William Morrow, 1987).

13 Niebuhr, Christian Realism and Political Problems, 130.

14 For more on the interpretation of evil in the Augustinian tradition, including that of Niebuhr, see: Charles T. Mathewes, Evil and the Augustinian Tradition (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

15 Juan Donoso Cortés, Essays on Catholicism, Liberalism, and Socialism: Considered in Their Fundamental Principles, trans. Rev. William McDonald (Preserving Christian Publications, 2014); De Maistre, Considerations on France; Joseph de Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues: Or Conversations on the Temporal Government of Providence (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993). Cf. Attila Károly Molnár, Idealisták és realisták (Idealists and Realists) (Századvég, 2023), 85–163.

16 Patterson, Christianity and Power Politics Today, 3.

17 Patterson, ‘Niebuhr and His Critics. Realistic Optimism in World Politics’, International Relations (August 1999); Reinhold Niebuhr, ‘Optimism, Pessimism, and Religious Faith’ [1940], in Robert McAfee Brown, ed., The Essential Reinhold Niebuhr (Yale University Press, 1986), 6; Biggar, What’s Wrong with Rights?, 17.

18 Saint Augustine, The City of God XI–XXII (Penguin Books Limited, 2003).

19 Niebuhr, Christian Realism and Political Problems, 138.

20 Niebuhr, Moral Men and Immoral Society, 109.

21 Niebuhr, Moral Men and Immoral Society, 110–111.

22 See: Miklós Papp, ‘A szeretet rendje’ (The Order of Love), Új Ember (25 January 2014).

23 Nigel Biggar, Behaving in Public: How to Do Christian Ethics (Eerdmans Publishing, 2011); and Nigel Biggar, Between Kin and Cosmopolis: An Ethic of the Nation (Cascade Books, 2014).

24 Biggar, Between Kin and Cosmopolis, 6.

25 Biggar, Between Kin and Cosmopolis, 10.

26 See: The Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith, ‘Doctrinal Note on Some Questions Regarding the Participation of Catholics in Political Life’, point 8.

27 Richard Swinburne, Free Will and Modern Science (British Academy, 2012); and Richard Swinburne, Mind, Brain, and Free Will (Oxford University Press, 2013); László Bernáth, Létezik-e szabad akarat? (Does Free Will Exist?) (Kalligram, 2023).

28 See the definition of ‘perszonalizmus’ (personalism) in the Magyar Katolikus Lexikon (Hungarian Catholic Lexicon), https://lexikon.katolikus.hu/P/ perszonalizmus.html.

29 Niebuhr, Christian Realism and Political Problems, 121; Cf. Saint Augustine, On the Trinity (Beloved Publishing, 2014).

30 For more, see the encyclical Fides et ratio of Pope Saint John Paul II, issued in 1998.

31 Niebuhr, Christian Realism and Political Problems, 115.

32 De Maistre, St. Petersburg Dialogues, 341–342. Tamás Nyirkos notes that de Maistre is wrongly called the ‘philosopher of the hangman’ and a proto-fascist, as the theme of the hangman at most accounts for forty pages in his seven-thousand-page oeuvre. Tamás Nyirkos, Az ötfejű sas. Teológia és politika a francia ellenforradalomban (The Five-Headed Eagle: Theology and Politics in the French Counter-Revolution), (Máriabesnyő, 2014), 17.

33 Saint Augustine, Contra Faustum Manichaeum, 22, 69–76.

34 H. David Baer, Recovering Christian Realism: Just War Theory as a Political Ethic (Lexington Books/ Fortress Academic, 2014); Nigel Biggar, In Defence of War (Oxford University Press, 2013); and Michael Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations (Basic Books, 1977).

35 Gergely Szilvay, ‘Kereszténység és kormányzás’ (Christianity and Government), in Gergely Szilvay, Káosz és kozmosz: reakciós gondolatok (Chaos and Cosmos: Reactionary Thoughts) (MCC Press, 2023), 429–430.

36 In a modern form, the Augustinian minimalist solution would be a neoliberal night-watch state supporting libertarian ethics—Augustinian liberalism does also exist. Cf. Eric Gregory, Politics and the Order of Love: An Augustinian Ethic of Democratic Citizenship (University of Chicago Press, 2008), especially Chapter Two.

37 Reinhold Niebuhr, The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1944). See also: J. S. Maloy, Democratic Statecraft: Democratic Realism and Popular Power (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

38 Niebuhr, Christian Realism and Political Problems, 53–73.

39 Zoltán Frenyó, Szent Ágoston és az augusztinizmus (Saint Augustine and Augustinism) (MTA Bölcsészettudományi Kutatóközpont – Szent István Társulat, 2018); Anthony Quinton, The Politics of Imperfection: The Religious and Secular Traditions of Conservative Thought in England from Hooker to Oakeshott (Faber & Faber, 1978); and Michael Bruno, Political Augustinianism: Modern Interpretations of Augustine’s Political Thought (Fortress Press, 2014).

40 Gergely Szilvay, ‘Politikus akcióban. Az „őrült szerzetes” és értékelvű pragmatizmusa’ (Politics in Action: The ‘Mad Monk’ and His Principled Pragmatism), Kommentár, 1 (2014).