The Eternal and the Changing

Many trends, ideas, even political philosophies can be interpreted as conservative. However, the adjective, conservative, especially today, says very little without an accurate definition. Whether someone is conservative or not, cannot be determined by ‘the aversion to new things’, and the ‘preference of something that he or she is already know.’ A conservative is not simply someone, who, in any given choice situation, prefers to stick to the option that ‘his or her predecessors’ would also most likely choose.

The fact that someone is conservative does not and cannot have the same, fixed meaning in every age. Especially not nowadays. Today, when the particularly aggressive forms of modernism have already destroyed almost all traditional social frameworks, religious forms, or customs, (or what is almost the same: distorted and falsified their own essence), it hardly makes sense to refer to what our immediate predecessors did or how they thought. These ‘earlier generations’, with few, mainly individual exceptions, accepted these modernistic systems of thought and conducts themselves, either as fellow travellers or as beneficial ‘collaborators.’ Clinging to a social custom or a specific institution—which has somehow survived, even though it may only be an ‘empty shell’ stripped of all its contents, is not conservatism, but merely conformism. Certain forms could even be filled with meaningful content– since the forms themselves only come alive when they are lived—however, there are few and fewer examples today of such a thing.

Even worse, if we define a conservative attitude simply as a mental setting that prefers the ‘familiar to the unknown, the near to the far.’ Something similar was written by Michael Oakeshott in his famous study ‘On Being Conservative.’

‘To be conservative, then, is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant, the sufficient to the superabundant, the convenient to the perfect, present laughter to utopian bliss.’[1]

Although the British author is undoubtedly right in his conservative rejection of utopianism, if a conservative were to associate with a type of person, who is constantly looking for security, who is ‘down to earth’, overly cautious and in a certain sense limited, we should call everyone who is unimaginative or cautious a conservative. This has already been done for us by the outright enemies of conservative thinking, for e.g. John Stuart Mill.

What does the ‘the commandment for preservation’ mean for the conservative today?

Preserving the ‘chain of generations’ unbroken and intact today, is a mere illusion. There has never been such a rift, or even a break, between the living conditions of successive generations as in the 20th and 21st centuries. The various ideologies of ‘progress’ have accelerated the cycle of existence to such an extent that the different generations are not only unable to adapt to the influx of the new technical and scientific phenomena, but all knowledge that is somehow non-rational and non-technical has lost its validity for the moderns. Every knowledge which is not technical, mechanical and rational, is a mere ‘antiquarian’ interest, ‘useless’ and even ‘ridiculous’ for the prevailing technocrats. Regarding the non-philosophical, the ancient knowledge related to farming and animal husbandry—which represented a non-negligible slice of the ‘heritage of our ancestors’ in relation to life on Earth—is almost completely useless in a world where the overwhelming waves of machines and digitalization have eradicated peasant societies themselves. Even the remnants of these knowledge, especially in the Western world, are disappearing, and there is no sign of any serious intention to return to the ‘ancestral way of life’, even not in the case of conservatives, since no one can compete with mechanized agriculture. In an ever-changing environment dominated by continuous innovation and change—call the so-called development sustainable or not—the ‘knowledge of our ancestors’ is no longer able to be used by the generations living today.

Nostalgia has not the slightest influence on the general course of the world, which is still entirely dominated by the idea of ‘efficiency.’ Modern science is by definition ‘constantly changing’ and this constant change requires constant, increased and accelerating adaptation from successive generations. As the pace of change accelerates, it’s as if each generation must learn everything all over again. In such circumstances, not only the interpersonal relationships are loosened, but also knowledge transfer chains are fragmented. The young do not understand the elderly, and the elderly are alienated from the young: the social dysfunction caused by the overuse of technology and too rapid change in the lives of families appears. Such was the transformation of the traditional multi-generational family into the ‘nuclear family’ as a result of the coercive processes of the modern economy from the 19th century. And today we are also witnessing the disintegration of ‘nuclear families.’

‘Nostalgia has not the slightest influence on the general course of the world’

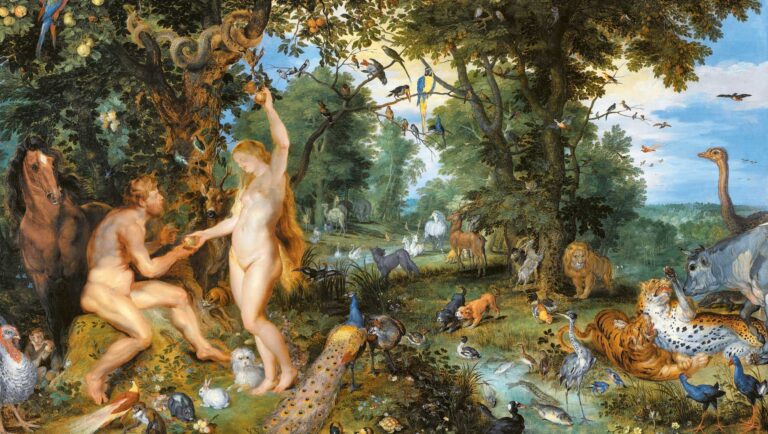

Modern conception of knowledge only considers as truly valuable one, that is aimed at technical applications and that is practical—all this is in complete harmony with the loss of the symbolic view of the universe. About society in the Middle Ages, writes Philip Sherrard:

[W]as an organic integrated society. It was a kind of sacred order established by God in which everything, not only man and man’s artifacts, but every living form of plant, bird, or animal, the sun, moon, and stars, the waters and the mountains, were seen as signs of things sacred (signa rei sacrae), expressions of a divine cosmology, symbols linking the visible and the invisible, earth and heaven. It was a society dedicated to ends which were ultimately supra-terrestrial and nontemporal, beyond the limits of this world.[2]

However, the ideology of empiricist scientific rationalism (scientism), which is widespread today, has nothing to do with the image of the kosmos in the original sense of the word. In such an understanding of the world, man has no place—just as historical time has no cause or quality. The ‘de-meaning’ of the worldview is something that has been going on since the so-called Renaissance—or even earlier. Today, however, even people who consider themselves religious rarely question the view of modernist natural science, which views the world (and perceives a human person) as a kind of set of physical objects ‘in themselves’ separated from spiritual principles—which are denied. Moreover, in this way of understanding the universe, things are constantly ‘evolving.’ Whether ‘religious’ or atheist, the modern Western man, with few exceptions, accepts the basic principle of development: this applies equally to the spontaneous (or even ‘influenced’ by divine intervention) development of life from what is said to be inanimate matter, the ‘development’ of human race (considered one of the animals), and the for the ‘development’ of social forms. (From ‘tyranny’ to ‘democracy.’) If this view were true, then any kind of conservatism is sheer absurdity: according to evolutionist assumptions, newer is always better as well. Only that which can adapt to environmental or social ‘challenges’ survives. In such circumstances, a reference to the ‘wisdom of the ancestors’ or ‘the unbreakable chain of the dead to the living and the unborn’ (Burke) becomes a mere platitude or, worse, a tasteless joke. What kind of ‘wisdom’ could those ancestors have, who themselves lived in unorganized and undeveloped conditions, whose knowledge of the world we classify as pure superstition, since they believed that the ‘Earth is flat’ and man was ‘created by God?’

There are very few people living in the world today—this ratio can probably be called roughly constant throughout known history—who dare to question the ruling ideas of our time, such as these prejudices about development, and thereby be able to create a real foundation of their conservative views. But even in their case, it should be explained what the conservatives want to preserve, and the person acting as a conservative should justify why the old is better than the new. One can do this with full authority only if you also declare that the ruling ideas of the modern world mean something that does not mean progress, but rather decline compared to previous conditions. In the face of a general decline, there is a need to preserve something that the ancients still knew, but the moderns no longer know.

What is this questionable knowledge?

It is clear that this knowledge cannot start from something that is relative temporal or practical: its starting point cannot be the relative positivity of one form of government over another. It is obvious that a traditional monarchy—in theory—is generally a more stable and safer form than a democracy that is subject to the will of masses, easily influenced and manipulated. However, politics itself is a highly contingent reality, and nothing in the world of politics is actually eternal. Although it seems obvious that human societies cannot exist without some kind of politics, simply ascribing a political and social character to conservatism is not enough. The value of a regime, a constitution, a system of power or a form of government can always be questionable compared to other regimes, systems of power or forms of government and constitutions, and political forms, in most cases, are not what they appear to be. For a long time, the Roman Empire presented itself as a republic, so-called monarchies and often republican or oligarchic regimes, and democracies—since it is actually impossible to build a solid form of government on ‘people’s power’ and ‘judgement’, in almost all cases they hide the power aspirations of a lone dictator or an oligarchic elite.

Conservative thinking also cannot be tied to a firm adherence to the agricultural or simply rural way of life, which is also a relative and time-varying, a rather ‘earth-bound’ starting point, the advantages of which are nevertheless obvious compared to the unnatural and unhealthy conditions of the modern urban way of life. Obviously, peasant societies are usually more conservative than urban ones. But this does not follow from the fact that these societies live off the land instead of machines, but from the fact that large-scale peasant societies (and also nomadic societies) seem to belong to an earlier phase in the history of humanity that had several implications for ‘transcending time and space.’

The basis of conservative thinking cannot be a false adherence to the social standard either, since customs also change in individual societies. Even in parallel, completely different customs may have existed in Rome during the royal period, the Athenian Democracy and the contemporary Persian Empire. The Hun Empire of the Roman Empire of the VI. century were completely different regarding customs and social standards. Yet all such customs—while often directly contradicting each other— can still be considered legitimate and ‘conservative.’ However, if so many variations are possible, which one should be stuck with or which one should be preserved? How could one impartially decide which system of customs is ‘correct’ and in accordance with the ‘laws of the universe’ and which is not?

‘The ideal of transcendence is more universal than Christianity’

Coherent conservative thought—contrary to the definition of ‘secular conservatism’ defined by Antony Quinton—cannot be one in which the existence of transcendence is not accepted as a basis of reference.[3] We don’t have to think here about the theology of a certain religion—since religions, like the forms of government, can be diverse, but about the idea of metaphysical transcendence. The concept of God can be thought of in many ways: as a personal creator god, as in Christianity, or as impersonal, even non-theistic transcendence, as in Buddhism and Taoism. It is also clear from this definition that conservative thinking and Christian thinking cannot be equated, although in terms of European history, these two had a pronounced affinity, since for a very long time in Europe the Christian religious form represented the central tradition that he displayed the idea of transcendence. However, the ideal of transcendence is more universal than Christianity and it is obvious that non-Christian societies outside of Europe were also organized around the idea of transcendence—before the arrival of modernity.

But why the idea of metaphysical transcendence so important to a conservative? Primarily because it is the only one that is not subject to the reality of time and space: that is, ‘God is what is constant, what does not change.’ An integral part of every possible definition of God is the assertion of its transcendence, since that which changes in time, would itself be subject to time. If we claim God as the source of time, if we really want to talk about God as absolute—then God is above change: that is, Eternal. If we claim that Eternity is possible, the fact of so-called ‘progress’ is relativized: the two are incompatible. The other option is to say that there is no ‘Eternal’ or ‘only change is eternal.’ At first glance, this seems like a serious dilemma. It is as if everything revolves around one assumption of the metaphysical transcendence. However, only superficial thinking sees this as a real question to be decided or a question of the ‘leap of faith.’ This dilemma is not real because the second possibility is a sophistry: if only change were the only constant, then no order and no coherence could be created—even not the coherence and order of the words to say and understand such a thing that ‘there is no coherence.’ ‘Constant change’ is an oxymoron in itself. What is constantly changing doesn’t exist, and if we didn’t exist, we wouldn’t be able to talk about ‘nothing’. Metaphysical transcendence—although it’s not ‘in’ the world, is a necessity, which cannot be not to be, as the phenomena of the world, the coherence of the words exists. It is not evident for everyone, because—to use a metaphor—God is not seen be anyone, not because it is invisible, but because it is cannot be seen—real transcendence also transcends senses. Those, who are believe only to their senses are at the same time limited and finally, also trapped by them. According to William Blake, the English romantic poet, a ‘heterodox’ Christian mystic and artist: imagination is the instance among human abilities that most closely resembles to God. It is our only ability that is free in all respects, and this overriding freedom reflects man’s original nature, his substance not affected by ‘original sin’. In one of his paintings Blake depicts Newton, one of the doyens of the new natural science, as ‘Urizen’ (formed from the word ‘Reason’), i.e. as a rationalist ‘demiurge’, as he constructs ‘time and space’ with his dividers. The Newtonian universe of ‘one-fold vision’ presupposes the tyranny of time and space for Blake, and time and space presuppose material determination. The ‘cosmos of time and space’—the universe of Enlightenment science—is not an unquestionable reality for Blake, but a limited way of looking at the world, a hotbed of determination.

If we accept the existence of transcendence as conservatives, we must also accept that everything that is outside the transcendent is sui generis subject to change. Change— and thus clearly also the fact of decline or progress—is made possible by transcendence as everything else ‘in’ the world. The existence of the ‘Eternal’—this is the particular knowledge that is the most important part of the ‘wisdom of the ancestors’ and it is what the moderns have forgotten.

[1] Michael Oakeshott, ‘On Being Conservative’, in: Rationalism in Politics, Methuen & Co., London, 1962, 168-197, 169.

[2] Philip Sherrard: Modern Science and the Dehumanization of Man. https://www.themathesontrust.org/papers/modernity/Sherrard-Modern_Science_and_Dehumanization.pdf (accessed: 2024. 09. 13.)

[3] See: Anthony Quinton: The politics of imperfection. The Religious and Secular Traditions of Conservative Thought in England from Hooker to Oakeshott. Faber and Faber, London, 1978. 13