‘Today, the only legal brake on the hegemony of EU law is the constitutional courts of the member states, which are empowered to filter out ultra vires EU acts or EU acts that violate national constitutional identity’ – Tamás Sulyok and Valer Dorneanu President of the Hungarian and Romanian Constitutional Court pointed out in a conversation on the role of the national constitutional courts in the European Union with Lénárd Sándor, Head of the Center for International Law at the Mathias Corvinus Collegium.

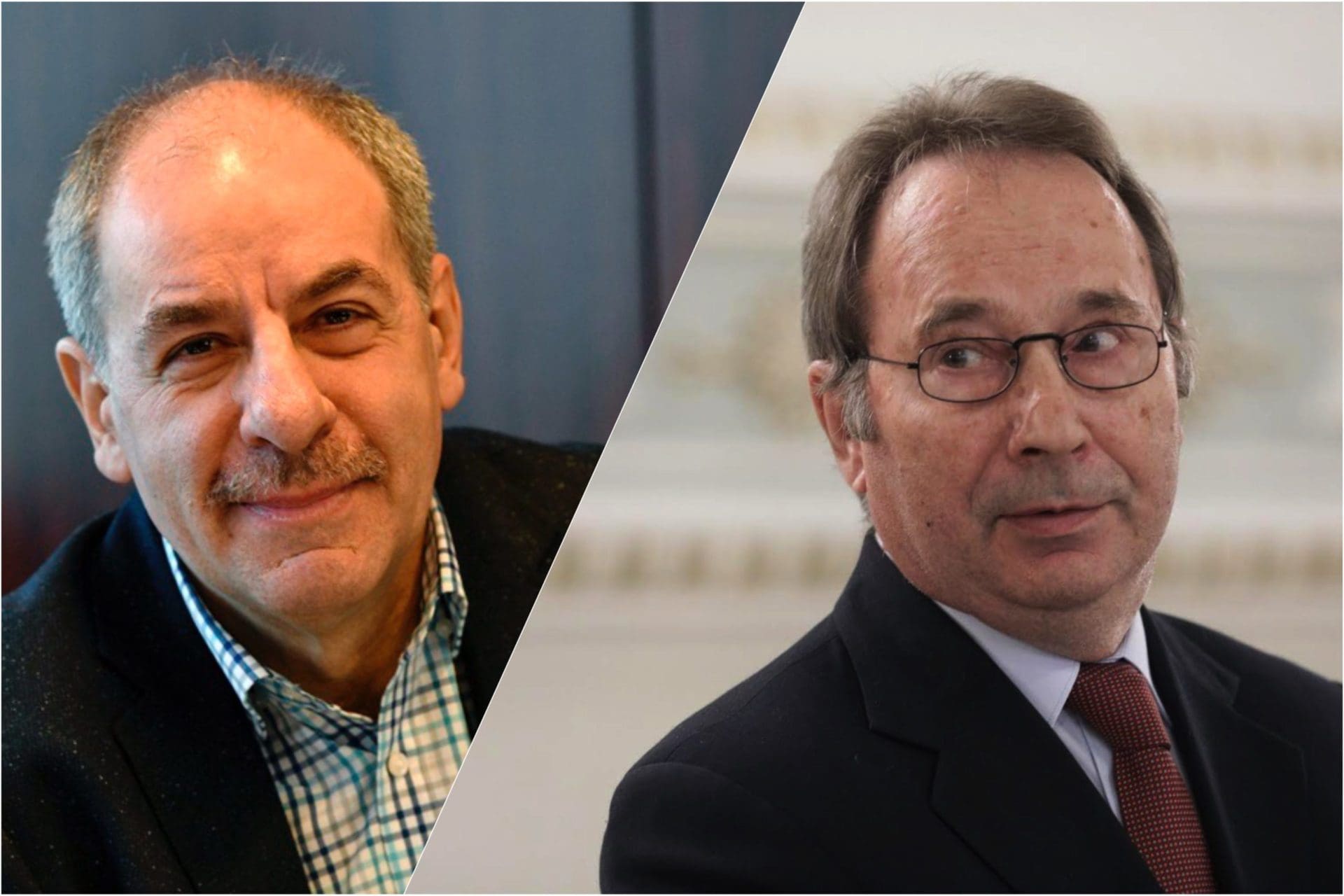

Tamás Sulyok was elected judge of the Constitutional Court by the Hungarian Parliament in September 2014 and since November 2016 he has been the President of the Court for the term of his mandate. He is a graduate of the Faculty of Law of the University of Szeged. Between 1982 and 1991 he was legal councilor, since 1991 until being elected as Member of the Constitutional Court he has been attorney at law. Between 2000 and 2014 he has been honorary consul for Austria. Since September 2005 he has been visiting lecturer teaching constitutional law at the Faculty of Law of the University of Szeged. He received his PhD in 2013. His field of research is the constitutional frames of advocacy.

Valer Dorneanu, university professor, was appointed judge of the Constitutional Court of Romania in 2013, for a term of office of nine years, and since 2016 he has been the President of the Court. He has served numerous functions and public dignities, including that of President of the Legislative Council (1995–2000), President and Vice-President of the Chamber of Deputies (2000–2008), Deputy People’s Advocate (2010–2013). He has a PhD in law. Dr Dorneanu is the author of numerous monographs, studies and scientific communications.

Lénárd Sándor: From its inception, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has been playing a pivotal role in developing the EU law as well as in defining its relation to national laws and national constitutions. However, we also witness that since the 1970s but especially in the past decade, constitutional courts or equivalent judicial forums of member states have been increasingly involved in reviewing the law along with exercising competence of the European Union based on their national constitutions. From a historical point of view, what have been the major roles of national constitutional courts in shaping the EU law as well as the European integration?

Tamás Sulyok: In the history of European integration, member states, and thus the supreme guardians of national constitutions, namely the constitutional courts, have generally played the role of the brake, while the driving force of the engine has been the CJEU. To avoid an accident, a balanced cooperation between the engine and the brake is needed. In the context of the EU, this is what the institution of what is known as the ‘responsibility for integration’ is intended to promote, making European integration a shared responsibility of the member states and the Community. Through the principle of primacy or direct applicability, which stems from the case-law of the CJEU, European law has been able to develop into a sui generis legal order, thus becoming equal to the national legal orders of the member states without the need for state sovereignty to be established behind it. This is undoubtedly a success story in which horsepower has driven the European wagon by ripping the brake pads off.

Today, the only legal brake on the hegemony of EU law is the constitutional courts of the member states, which are empowered to filter out ultra vires EU acts or EU acts that violate national constitutional identity

Today, however, the situation has changed: decisions of the CJEU interfere with the constitutional order of the member states to an extent that justifiably triggers the brake effect against the unjustifiably unleashed engine. Today, European law, which had previously been on an equal footing, seems to be seeking hegemony over the legal systems of the member states, no longer merely to harmonize them, but to incorporate them in a furtive federalism. All this is being done under the pretext that the EU alone has the responsibility for integration and that the member states are its sworn enemies, against whom EU law must be defended. Today, the only legal brake on the hegemony of EU law is the constitutional courts of the member states, which are empowered to filter out ultra vires EU acts or EU acts that violate national constitutional identity by assessing the EU authorizations conferred by the national constitutions. The constitutional courts remain the institutions providing the legal brakes on integration, while the legal engine of integration remains the CJEU.

L. S.: Historically, how do you see the role of national constitutional courts and other equivalent judicial forums in the European integration?

Valer Dorneanu: The accession of a state to the European Union implies the existence of a set of converging values, which allow national rules to be compatible with those of the supranational structure, in turn based on the European legal heritage. Once the national Parliament has approved the Act of Accession, it is for the national authorities and institutions to achieve this convergent settlement of values in relation to political obligations. In this regard, I would also mention Article 148 (4) of the Constitution of Romania, which provides that state authorities shall ensure that the obligations assumed by the Act of Accession are fulfilled.

The constitutional courts, from the point of view of this relationship, have the power to ensure that this compatibility is achieved, but at the same time they have the difficult task of ensuring the supremacy of the Constitution in the given context. The methods of interpretation of the Constitution, ranging from originalism to living law, make possible the rapprochement between the aforementioned tasks and I believe that the vast majority of constitutional courts have chosen the most appropriate method of interpretation to achieve the purpose of accession.

The focus has always been on the collaboration and dialogue in the European judicial area, and, as such, the relationship between the CJEU and national constitutional courts must also be characterized by the same parameters. I consider the preliminary ruling procedure to be very useful in this regard, which, moreover, the Constitutional Court of Romania used in November 2016. This procedure allows for the view of the European court to be heard in a given matter and the constitutional courts will be able to express an appropriate point of view. This is especially useful because both courts are grounded on a common/identical set of values whether enshrined in the Constitution or in the basic treaties.

But all this does not lead to a “decay” of constitutional courts; on the contrary, as they are the closest to the national ethos, being in the best position to achieve—through dialogue and openness—the rapprochement between the two levels, which are essentially based on the same values. To conclude, I believe that constitutional courts have had, have and will have a particular role in the coming period in achieving this axiological convergence between national and supranational.

L. S. Jacques Delors used to compare the European integration to a bicycle: if it is not in motion, it falls down. The European Union has been expanding both geographically as well as in terms of the subject-matter it aims to regulate. How do these developments affect the roles of the national constitutional courts? What challenges do these developments pose?

T. S. The bicycle analogy highlights a different side to the engine parable. Indeed, integration is moving forward at an unstoppable pace, as can be seen from the history of the founding treaties or indeed from the incorporation of the Charter of Fundamental Rights into the Treaty: an economic community aspiring to become a union of values.

The role of the constitutional courts is growing in importance in direct proportion to the progress of integration. It is precisely the integrity of the legal systems of the member states that needs to be protected against the encroachment of EU law on their competences. Indeed, the decisions of the CJEU are already calling into question fundamental principles such as the erga omnes scope of national constitutional court decisions, without which there can be no constitutional justice. If this process continues to escalate, it will be difficult for national constitutional courts to put the brakes on the European wagon that is on the downhill slide. I believe that it is wrong to start from a common-sense view of the situation that integration must be imposed from above. In my view, integration is a delicate historical process that should be characterized not by coercion but by a continuous, multifaceted and meaningful dialogue. If we do not return to the fair and mutually respectful cultivation of the Gerichtsverbund, as proposed by Andreas Voßkuhle, it will lead to a legal disaster on the European road. The only form of symbiosis between the 27 member states and the European legal system within the framework of the current Treaties is an intensive and egalitarian dialogue between the CJEU and the national constitutional courts.

L. S. Many thinkers point out that—based on different historical experiences and attitudes—there is a fissure between the Western and Eastern halves of the European Union. What unique approach do constitutional courts in the Central and Eastern European region have vis-à-vis the European Union?

V. D. The East and the West have indeed been treated in European historiography as promoting two cultural paradigms, distinct but united by the force of common principles and values. Personally, I do not believe that there is a crack between East and West in terms of constitutional principles and of a constant concern in order to guarantee fundamental rights and freedoms, in other words, the protection of human dignity (see Judgment of the German Constitutional Court 2 BVerfGE 45, 187, in which the object-subject formula was imposed in the analysis of the human dignity concept, a formula common to all EU member states). The democratic values we support and promote are the same. They constitute a genuine lingua franca of constitutional courts.

At the same time, I emphasize that cooperation between constitutional courts is based not on geographical criteria, but on axiological ones. Of course, geographical proximity facilitates the exchange of ideas, and the new methods of online communication also proved extremely effective. It is an axiom the fact that where values are either close or similar, cooperation will exist. I will give you an example: the relationship with the Constitutional Court of Hungary, an excellent relationship created on a shared value substratum and a superlative interpersonal communication. We would like such relations with any constitutional court in the EU.

I must admit that I do not share the idea of regional coalitions of constitutional courts, but I believe that an association of constitutional courts or other forms of cooperation is based on the sharing of a set of constitutional values, which constitutional courts promote, whether they are from Spain, France or Hungary, Romania. That is why I strongly believe that constitutional courts must work together, regardless of the geographical criterion, areas from which they belong to, because a strong EU is based on constitutional structures that embrace and spread values specific to this area. At the same time, I appreciate that the idea of such a crack should not be promoted from top to bottom or from bottom to top.

I strongly believe that constitutional courts must work together, regardless of the geographical criterion, areas from which they belong to

L. S. The European integration is expanding and applies in a huge number of areas beyond the original largely economic areas in the EEC Treaty and thus more often intertwine with national constitutional values and political aspirations. This sets the stage for tensions in areas such as asylum, immigration, privacy or national security. How can judicial dialogue ease this tension in your view? Can we address this dialogue in terms of hierarchy, or should we rather think of it in other terms?

T. S. The dialogue between the courts discussed here is also a dialogue between legal systems of equal status. It is; therefore, first and foremost about values. It is not about different values, but about the diversity of values in the European legal area, which is also a fundamental element of our European identity. Therefore, a common respect for values must be the basis for this judicial dialogue. Moreover, unlike political discourse, dialogue between courts is always precisely traceable, since it can be seen in the specific form of the way in which judges reflect on each other’s decisions. Since it is a dialogue between legal systems of equal status, it cannot be conceptually hierarchical either, the 28 + 1 legal systems are not in a situation of subordination to each other, but rather in a situation of equal networking. Unfortunately, this is not always the case in the recent decisions of the CJEU.

L. S. As the scope of the integration is continuously expanding, the consensus among member states tend to weaken in certain areas. However, the stakes are enormously high as member states can decide to leave the European integration altogether. Some thinkers point out that the European Commission and the CJEU could only serve as the ‘engine of integration’ because there was a strong consensus among the member states on the need to create the internal market or the common competition rules for example. But what are the limits of the supranational approach including the judicial interpretation of the Founding Treaties and when should this give way to the compromises of member states? When is judicial dialogue useful and what are its limits in your view?

V. D. Indeed, Europe is an idea on the move which is defined, configured and structured over time and as areas of integration become more visible and substantial. We must recognize that extending the areas falling within the exclusive or even shared competence of the European Union, often through an overly creative case-law of the CJEU, is a challenge for the constitutional courts. Slowly, the case-law of the CJEU has become ubiquitous in many areas, so the assessment of the constitutionality of a law has become an extremely delicate task. There is a dialogue in the case-law leading to paradigmatic changes in the European constitutional area.

Let me make a comparison between the case-law of the Constitutional Court of Romania on issues of European law in the first years after the accession and the current one, 15 years after the accession. If we were initially reluctant to refer a question to the CJEU for a preliminary ruling, we would now not only identify the need for such a question, but also refer the matter to the CJEU. Secondly, since 2011 we have developed the doctrine of the interposed norm, which involves the acceptance of the EU norm in the assessment of the constitutionality of the national legal provision (Decision No 668/2011). The accurate application of this doctrine is the challenge that I see in the future, because the Constitutional Court of Romania must assess the extent to which a EU norm has constitutional relevance in order to be able to use it as an interposed norm in the constitutional review. However, once this has been established, it means that that EU norm will be a criterion for interpreting the constitutional norm itself. If, at first, we shaped this doctrine, we would now thoroughly apply it. Thirdly, the question arises of that level of scrutiny that the Constitutional Court must demonstrate in the competences assigned and shared with the EU.

The limits of the dialogue lie within the limits of the basic treaties – the ultra vires doctrine and the national constitutional identity are both concepts which were found and applied in the case-law of the German Constitutional Court

You asked me about the limits of the dialogue between constitutional courts and the CJEU. I believe that this is based on the correct interpretation of Articles 3 and 4 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) with reference to the exclusive and shared competences of the EU and Article 4 (2) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) as to the fact that the EU respects the national identity of the member tates, inherent in their fundamental political and constitutional structures. From a judicial point of view, this is the task of the CJEU, given that it has the power to interpret the provisions of the basic treaties. But I cannot help but note that there are certain specific situations involving tension between the national and supranational levels. The procedural solution is the dialogue, the path of the preliminary question, a dialogue which cannot be achieved through vertical steps (from top to bottom), but through horizontal ones. The limits of the dialogue lie within the limits of the basic treaties – the ultra vires doctrine and the national constitutional identity are both concepts which were found and applied in the case-law of the German Constitutional Court. The concept of national constitutional identity can be found in a similar form in Article 4 (2) TEU, so that it requires active cooperation between the national and supranational levels, the latter being unable to establish the sphere of constitutional identity of a State. Constitutional courts must not only be heard, but also listened in order for the judicial outcome to be fair.

I do not hide the fact that the Constitutional Court of Romania, by Decision No 390/2021, addressed the issue of national constitutional identity, since the Constitutional Court established that the priority of applying the European norm should not be perceived in the sense of removing or disregarding the national constitutional identity, as a guarantee of a substantive identity core of the Constitution of Romania and which should not be relativized in the process of European integration. By virtue of this constitutional identity, the Constitutional Court is empowered to ensure the supremacy of the Fundamental Law on the territory of Romania. Similar ideas are also found in the case-law of the German Constitutional Court (Judgment of the Second Chamber of the Constitutional Court of 30 June 2009, in Case 2 BvE 2/08, concerning the constitutionality of the Treaty of Lisbon, Judgment of the Second Chamber of the Constitutional Court of 5 May 2020, in Cases 2 BvR 859/15, 2 BvR 1651/15, 2 BvR 2006/15 and 2 BvR 980/16). Decision No 390/2021 continues the previous line of the case-law of the Constitutional Court. Thus, by Decision No 683/2012, the Constitutional Court referred to the national constitutional identity, which, even in the terms of the compliance clause contained in Article 148 of the Constitution itself—according to which Romania cannot adopt a legislative act contrary to the obligations to which it has committed itself as a member state—has become a constitutional limit in the application of that compliance clause (see Decision No 64/2015 and Decision No 887/2015).

At the same time, I would point out that the position of the Constitutional Court of Romania is not unique, since it was the constitutional courts in France or Germany that identified and capitalized the ultra vires doctrine, as well as the concept of national constitutional identity.

Finally, I would point out that the constitutional courts must not be concerned about political decisions relating to the departure from the EU by a member state, but rather about achieving integration within the conditions and limits of the Constitution.

L. S. The Hungarian Constitutional Court recently handed down a major decision concerning the joint exercise of the competence of the European Union. What unique approach does it take and what are its major conclusions?

T. S. The Hungarian Constitutional Court has taken two important approaches in this abstract interpretation of the Constitution. It seeks an answer to the topical question if European law is not effectively implemented for whatever reason, is a member state entitled to exercise the—non-exclusive—EU competence which it has conferred on the Union until such time as its effectiveness (effet utile) is restored. More specifically, if a member state is disadvantaged by the incomplete and unenforced implementation of international treaties concluded by the Union, for example, in that it cannot return foreign nationals illegally staying in its territory to another state, the question arises whether the member state can temporarily exercise the joint competence to remedy the unlawful situation. The panel answered this question in the affirmative, applying the principle of reserved sovereignty already elaborated in one of its 2016 decisions. This approach highlights the fact that the requirement of an ever closer union vis-à-vis the member states is not only a political one, but also a matter of public law, and that—as a consequence—the joint exercise of competences is not an end in itself, but a legal instrument whose application is a precondition for its being more effective than the exercise of national powers in achieving the objectives pursued. In other words, the joint exercise of competences by the Union must in any case be justified by the member states and cannot be regarded as an obvious determination of the direction in which the historical process has developed.

In the second approach, the Constitutional Court sought a legal solution to the question, open to the whole of Europe, of whether the state is obliged to give constitutional protection to the traditional social environment of man. The Constitutional Court ruled that a person is born into a predetermined linguistic, cultural, ethnic and religious environment, and that these circumstances, as natural constraints determined by birth, are very difficult to change, but that they do influence an individual’s personal identity in a certain way and constitute an element of the right to human dignity as a fundamental right. The state, in its duty of institutional protection to safeguard this fundamental right, is under an obligation to ensure that changes in the social environment in which a person lives do not cause significant harm to these elements of identity. Where, for example, mass migration or other causes are capable of having such an impact, the state must protect the people living in its territory by legal means against the negative effects of the reorganization of their traditional social environment. Although not relevant to this particular case, I find it thought-provoking that a significant proportion of Orthodox Jews living in Western European states have been forced to leave their traditional social environment due to inadequate state protection, but that the traditional social environment of the lives of citizens of other states is also directly affected by social influences against which states often fail to provide adequate legal protection. The Hungarian State has now become constitutionally obliged to do so.

L. S. How do you see the path taken by the Hungarian Constitutional Court? Judicial forums in most member states do not recognize the absolute primacy or supremacy of EU law while they protect their own constitutional identities, sovereignty, self-identities or fundamental rights as provided in their respective constitutions. What approach does the Romanian Constitutional Court take in this regard? What are the limits of the supremacy of EU law and to what extent is it justifiable that constitutional courts guard over the core provisions and values of their constitutions?

V. D. The decision of the Constitutional Court of Hungary of 7 December 2021 can only be classified as a decision originating from a constitutional court and as such is generally binding. Sovereignty justifies subsidiary intervention by the member state in areas of shared EU-member state competence, as a safety valve until European fora intervene properly.

In Romania, the Constitutional Court’s reliance on EU law is consistent, following the case-law initiated by Decision No 668/2011, according to which ‘the use of an EU norm in the context of the review of constitutionality as an interposed norm to the reference one implies, pursuant to Article 148 (2) and (4) of the Constitution of Romania, a cumulative conditionality: on the one hand, that norm must sufficiently clear; precise and unequivocal in itself or its meaning must have been determined in a clear, precise and unequivocal manner by the Court of Justice of the European Union and, on the other hand, the norm must be limited to a certain level of constitutional relevance, so that its normative content may support the possible infringement by national law of the Constitution – the only direct norm of reference in the context of constitutional review.’ Therefore, the contradiction between the national and the EU norms does not per se constitute a breach of the norm of reference in the review of constitutionality, namely the Constitution, but may be an argument to demonstrate a breach of the Constitution.

Therefore, in its case-law, the Court has held, for example, that the provisions of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union have such constitutional relevance and may be used in the context of the review of constitutionality (Decision No 1479/2011 or Decision No 967/2012). In that regard, the Court has held that the provisions of the Charter are applicable to the review of constitutionality in so far as they ensure, guarantee and develop constitutional provisions relating to fundamental rights, that is to say, in so far as their level of protection is at least equal to that of the constitutional human rights standards. On the other hand, the Court has held that the provisions of Council Directive 2006/112/EC of 28 November 2006 (Decision No 354/2013) or of European Commission Decision No 928/2006 establishing a mechanism for cooperation and verification of progress in Romania to address specific benchmarks in the areas of judicial reform and the fight against corruption are of no such relevance and cannot be used for the purposes of constitutional review (Decision No 137/2019, par.78). I would point out that, as regards the European Commission Decision No 928/2006, the Court has held that, even if it is not a norm of reference in the context of the review of constitutionality, it is a European act binding on the Romanian State (Decision No 137/2019, par.77), thus maintaining its line of case-law established by Decision No 2/2012.

The Constitutional Court of Romania makes an important distinction between the primacy and the priority of European law. Conceptually, the former does not exist because it presupposes different normative levels within the same system. The European order is not part of the national one, since the European one constitutes a ‘new legal order of international law, in favour of which the States have limited their sovereign rights’ (Judgment of the CJEU of 5 February 1963 in Case C-26/62- van Gend en Loos). On the other hand, the priority of European law is the concept which is substantially correct and must therefore be used because it expresses a priority for the application of one system in relation to another regardless of the normative level of the act issued by the latter; thus, a norm applies as a matter of priority precisely because it is a ‘law’ that has been issued at EU level, regardless of the European body/authority/entity. Moreover, even in France they speak of primauté du droit européen. It is true that, in the case-law of the Constitutional Court of Romania, the priority of application of the European law system does not apply to constitutional rules. In other words, the priority of application of the EU norms concerns the infra-constitutional level. Such an approach is explained by the fact that there is an express constitutional provision [Article 148 (2)], which refers to the priority of application over domestic laws and not over the Constitution. The aforementioned constitutional provision was regarded by the Constitutional Court as expressing an inherent identity essence of constitutional nature. In this context, a certain difference between the case-law of the Constitutional Court of Romania and that of the CJEU is well known (see the CJEU Judgment of 21 December 2021 in case C-357/19).

The European order is not part of the national one, since the European one constitutes a ‘new legal order of international law, in favour of which the States have limited their sovereign rights’

As to the latter judgment of the CJEU, which interprets the Article of the TFEU on the protection of financial interests, the question arises as to whether it could be applied as a matter of priority in relation to the constitutional obligation of the state to protect fundamental rights and freedoms and to structure the powers of public authorities to combat corruption offences. When public authorities themselves violate these obligations, it is the role and purpose of the Constitutional Court of Romania to restore them and place their action within a constitutional framework. Specifically, the Constitutional Court of Romania defended the principle of objective impartiality of the judge, an element of the right to a fair trial, and that of legality, putting an end to the High Court of Cassation and Justice’s practice of introducing contra legem its president in the composition of the five-judge panels existing at its level (Decision No 685/2018). At the same time, the Constitutional Court of Romania defended the principle of legality when it sanctioned the non-establishment of specialized panels on corruption offences at the level of the High Court of Cassation and Justice, whereas the law itself laid down the obligation to establish them already in 2003 (Decision No 417/2019). The Constitutional Court of Romania defended the principle of legality and the right to a fair trial when it established the exclusive competence of the prosecutor and the criminal investigation bodies to execute the technical supervision mandate (Decision No 51/2016), and when it excluded the competence of the Public Ministry – Prosecutor’s Office attached to the High Court of Cassation and Justice to conclude protocols of cooperation with the Romanian Intelligence Service (Decision No 26/2019). Neither of those decisions was aimed at creating impunity in respect of acts constituting serious offences of fraud affecting the financial interests of the Union or of corruption, nor the removal of criminal liability in respect of those offences.

In other words, does the defence of the EU’s financial interests at any cost justify sacrificing the axiological substance of a Constitution? It is hard for me to conceive such a thing and to believe in approaches like aut Caesar aut nihil.

Furthermore, in this context, I note that the CJEU recognizes, in its Judgment of 21 December 2021 (C-357/19), the binding nature of decisions of the Constitutional Court. However, the conclusions of the CJEU ruling that the effects of the ‘principle of the primacy of EU law’ are binding on all organs of a member state, without national provisions, including those of a constitutional nature, being capable of preventing it, and according to which national courts are required to disapply of their own motion any national legislation or practice contrary to a provision of EU law, require the revision of the existing Constitution. In practical terms, the effects of that judgment can take place only after revision of the Constitution in force, which, however, cannot be carried out by operation of law, but only on the initiative of certain legal subjects, in accordance with the procedure and under the conditions laid down in the Constitution of Romania itself.

Therefore, the basic values enshrined in the Constitution of Romania are guaranteed by the Constitutional Court of Romania and, in relation to the CJEU, they must be reconciled only in so far as, by means of interpretation, such approximation can be achieved. In this regard, the most appropriate thing to add is salus populi suprema lex esto (Cicero, De legibus), that is ‘Let the welfare of the people be the supreme law’.

L. S. Article 2 of the Founding Treaty enumerates some of the values that are common in the European integration and in its member states. Are these values organized in a bottom-up or a top-down approach in your view? What are the downsides of interpreting these values in a centralized way as abstract ideas that are extraneous to member states? What role subsidiarity play in these dilemmas? I am wondering how the pluralistic constitutional heritage of Europe can be best preserved when these values are being interpreted.

T. S. The system of values developed in society has essentially moral, legal, political, economic, religious and cultural elements. According to this approach, the values listed in Article 2 of the TEU are legal values on which the Union is based and which are common to all member states. It clearly follows from this formulation that the EU cannot represent values other than those which are common to the member states. Behind the elements of value in national legislation lie community values based on the principle of popular sovereignty. Therefore, if the requirements of democracy and the rule of law listed in Article 2 TEU are taken into account, only member states can make primary declarations of values, and the institutions of the Union, which do not embody statehood and popular sovereignty, are clearly unsuitable for this. The depositaries of values are therefore the member states. The solution lies in a possible convergence of values, for example through a dialogue between courts on the basis of equality.

As I said earlier, the diversity of values is a defining element of European identity, a tangible expression of unity in diversity. This does not weaken our Europeanism, but strengthens it.

The principle of subsidiarity indirectly supports national identity and pluralism of values, but it is also a way of reducing the negative effects of the Union’s democratic deficit. The principle of subsidiarity in itself supports the thesis that the existence of EU values is national in origin.

L. S. The principle of “an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe” was already included in the Rome Treaties. However, in the course of the history of the European integration, the meaning of this principle has shifted and became the symbol of an integration that is the end goal in itself and will substitute Member States over time. As opposed to this vision, there are those who insist that the European integration remains to be an instrument although a necessary and precious one. In their view, the end goal of the integration is the Member States. How do you see this dilemma between the “end goal” and “the instrument”?

V. D. The answer to your question requires an in-depth analysis of the Lisbon Treaty and involves a significant political load. The evolution of political thinking and mentalities is also an indicator in this respect. It is the time that will demonstrate whether the Member States are the purpose or the tool of integration. For the time being, they are the tool of integration.

Moreover, by Decision No 683/2012, the Constitutional Court of Romania emphasized that of the essence of the European Union is the conferral by the member states of powers—more and more in number—in order to achieve their common objectives without, of course, ultimately undermining the national constitutional identity by that transfer of competences. Therefore, in this line of thinking, the member states retain competences which are inherent in order to preserve their constitutional identity, and the transfer of competences as well as the rethinking, increase or establishment of new guidelines within the competences already transferred fall within the constitutional discretion of the member states.

L. S. The recently launched Conference on the Future of Europe initiative aspires to provide a forum for discussion about the potential reforms of the EU as well as about the future of the European continent. Hence, it also offers a unique opportunity to discuss questions concerning the reform of the competences or the composition of the CJEU as well as the interplays of national constitutional courts and the CJEU. What reform steps would you think worth considering in order to achieve a harmonious cooperation as well as an equilibrium that aims to better respect the constitutional structures and identities of the member states? What reform steps should be necessary to encourage a cooperation between the CJEU and national constitutional courts that is sincere and fruitful?

T. S. I do not think that the future of Europe, our own common future, is a simple question that can be settled once and for all in a conference, although such solutions may sound very comprehensive from the outside. The future of Europe must be determined by the peoples of the member states, starting from the democratic will of the member states, which alone have the sovereignty of the people, and reconciling them while maintaining the principles of mutual respect, equality and loyalty between member states. The path from the lower to the upper is always more difficult than the path of solutions devised from above, but the fundamental values of democracy and the rule of law do not allow the European Union to take any other path than this more difficult one.

It would be very important to make it clear that the competences of the CJEU do not extend to the interpretation of national constitutions

With regard to the powers of the CJEU, it would be very important to make it clear that its competences do not extend to the interpretation of national constitutions, just as national constitutional courts are obliged to respect the CJEU’s exclusivity in the authentic interpretation of EU law. However, it should also be made clear in the rules that in the European legal area, 27 national legal systems and one EU legal system coexist on an equal footing and that EU law does not take precedence over the identity core of national constitutions, since such a view would result in a hierarchical relationship between legal systems, with the CJEU having the final say in cases of conflict between EU law and national constitutional law. The CJEU could thus become the main depositary of judicial power throughout the EU, thus removing the role of national constitutional courts as a check and balance to review EU acts on the basis of national constitutional authorizations or national constitutional identity. To avoid this situation, it would be necessary to lay down rules in the Treaties guaranteeing the equality and autonomy of the 28 legal systems, since, as I have said, the situation has now changed in the direction of a need to protect the integrity of the core of national constitutions against the aspiration for omnipotence of EU law. At the heart of a judicial dialogue mechanism that mutually protects the equality and autonomy of legal systems in the European legal area could remain the well-established preliminary ruling procedures, but the rules need to be complemented by a procedure whereby the CJEU can refer to the national constitutional court any time a case before it raises a problem of national constitutional identity in relation to national constitutional rules, in order to protect the principles of equality, subsidiarity and the autonomy of legal systems. In this procedure, the national constitutional court would have the possibility to explain the national constitutional context of the specific case before the CJEU, which the CJEU would have to take into account in its decision, reflecting in its reasoning on the decision of the national constitutional court. In addition, the national constitutional courts should also be able to express their opinion on cases before the CJEU which have any connection with national constitutional law, on the basis of their own decision, as an independent actor of the litigants, which the CJEU would be obliged to take into account in its decision and reflect in its reasoning. This procedure could, of course, be reciprocal, that is, the CJEU could also have a similar position in the proceedings of the national constitutional court. This system would finally give the European judicial dialogue—the Gerichtsverbund described by Andreas Voßkuhle and Armin von Bogdandy more than a decade ago—a solid legal basis in European law, and would strengthen reciprocity between courts, while ensuring that the principles of equality and subsidiarity are duly respected. The current situation is quite absurd: a national constitutional court has no procedural standing before the CJEU, but can, at most, lobby the national government to express the position of the constitutional court before the CJEU, a situation which is a serious violation of both the separation of powers, a fundamental principle of the rule of law, and the principle of judicial independence. Recently, the Romanian Constitutional Court has been the victim of this very situation, as President Dorneanu tells us more about this.

Nevertheless, I do believe that, under the current procedural rules, the CJEU would still have the possibility to refer specific questions to the national constitutional court of a member state if a question of national constitutional law is raised in the case before it, as the former president of the Slovenian Constitutional Court, Rajko Knez, has already raised. Such a request could serve the same purpose as the initiation of a preliminary ruling procedure before the CJEU by a constitutional court.

I firmly believe that the equality and autonomy of the 28 legal systems operating side by side in the European legal area on the basis of the principle of networking is guaranteed by a Gerichtsverbund based on mutual respect, and I myself believe that the time has come for European law to finally make this concept, which is of essentially scientific origin, a binding legal term for everyone. Until this is done, I would encourage the CJEU, while applying the solution that already exists in the area of positive law, to have the courage to reach out to the constitutional courts of the member states when it is deciding on a question relating to the constitutions of the member states.

L. S. How would you increase the efficiency of the dialogue between the European and national judicial forums to achieve a more harmonious interpretation of the EU law that also pay careful attention to the requirements of national constitutions? What public law reforms would you suggest?

V. D. A short and frank answer: the supranational level needs to identify a constructive and appropriate way of institutional dialogue with constitutional courts. This way of dialogue must be carried out on an equal footing, without the possibility of creating or establishing hierarchies. Thus, I consider that, when cases concerning the Constitutional Court case-law are pending before the CJEU, a procedure for consulting that Constitutional Court must be carried out, by default, and, where the case in question relates to a matter of principle with regard to the jurisdiction or the role of constitutional courts, this consultation procedure must be carried out with all constitutional courts in the EU.

In this consultation procedure, constitutional courts may be invited to express an expert opinion or point of view. Otherwise, the dialogue between constitutional courts and the CJEU would suffer. This implies an amendment to the Rules of Procedure of the CJEU, but I believe that all member states would agree to such an approach. The CJEU must respect the particular role that national constitutional courts play in national law, and I am therefore fully confident that this role cannot be impaired, but only strengthened through a mutual consultation procedure.

My proposal is made precisely in view of the recent experience of the Constitutional Court of Romania. More specifically, in 2019, the High Court of Cassation and Justice of Romania (HCCJ) and the Tribunal of Bihor , Romania referred two questions for a preliminary ruling to the CJEU (Cases C-357/19 and C-379/19) directly concerning the Constitutional Court Decision No 685/2018 and Decisions Nos 51/2016 and 26/2019 respectively. As our Court had no legal standing in the case, we formulated two amicus curiae opinions, which were communicated to the CJEU. The latter subsequently returned the aforementioned opinions on the grounds that there was no provision in the Rules of Procedure of the CJEU allowing for such a dialogue. Following that reply, the Constitutional Court communicated its point of view to the Romanian government agent at the CJEU/ Ministry of Foreign Affairs, without however knowing whether the Constitutional Court’s arguments had been upheld in the Government’s viewpoint. In any event, it is not advisable for a constitutional court to approach the government in order to have the necessary dialogue with the CJEU. The route of communication between the two courts should be direct, transparent and carried out on an equal footing.