In recent years, sections of the Western media have cultivated a tone of unrestrained scaremongering in their denunciation of Hungary. Predictably, the announcement of the general election in Hungary in April 2021 has led to a further escalation of anti-Orbán propaganda. Anti-conservative members of the European Parliament are lining up to demand that the Hungarian elections should be carefully overseen by foreign observers.1 Agence France-Presse is launching a website to fight disinformation in Hungary. ‘We are proud to be participating in this innovative initiative to help in the fight against disinformation in Europe, a major challenge for our democracies’, said AFP Global News Director Phil Chetwynd.2 The arrogant neo-colonial tone adopted by Chetwynd has as its premise the belief that the people of Hungary cannot be trusted to make the right choices without the benevolent support of Western information experts.

This neo-colonial tone was in full display when Lisa Nandy, the British Labour Party’s shadow secretary for foreign and Commonwealth affairs reacted hysterically to the visit by Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orbán to Downing Street in London. Her denunciation of Orbán communicated the arrogant colonial mentality directed at people who are not ‘like us’. In a series of tweets Nandy accused the Hungarian government of all manner of misdeeds, from undermining civil liberties to anti-Semitism.3 If Nandy’sfantasy depiction of the situation in Hungary corresponded in any way to reality, Budapest would be just a couple of months off its own version of Kristallnacht.

The principal motive fuelling a propaganda war against the supposedly authoritarian regime in Budapest is the concern that by its very existence Hungary is setting a bad example to the people of the European continent. From this perspective, Hungary must not be allowed to continue to defy the EU and its ‘woke’ values. The EU does not want the Hungarian model to serve as an inspiration to others. As Zoltán Simon, a commentator at Bloomberg, explained, the reason why the EU has attempted to punish Hungary is that ‘Orbán’s model was spreading in the bloc’:

‘In 2015, the nationalist Law & Justice party took power in Poland, pledging to emulate Orbán’s policies. In Slovenia, another populist ally of Orbán, Janez Janša, took power. Italy’s Matteo Salvini and France’s Marine Le Pen have also forged close ties with Orbán, seeing in the Hungarian leader’s track record a recipe to subvert mainstream politics in their own countries. In a bid to overhaul the EU, Orbán has also tried to unite European nationalist parties, though he’s so far failed. In the US, former President Donald Trump and the right-wing establishment have taken notice, with Trump even endorsing Orbán for April’s election.’4

According to Simon, should Orbán lose, the EU could breathe a sigh of relief. As a bonus, such a defeat would ‘also isolate Poland’s ruling party in its own standoff with the EU and inspire opposition parties there to unite’.

In the eyes of the EU oligarchy and the mainstream Western media, Orbán personifies what they fear the most, the spectre of populism. They despise the traditional and conservative values associated with populism and are therefore determined to prevent their spread to other parts of Europe.

The Liberal Elite on the Defensive

For some time now, American technocratically oriented liberalism and its European equivalent have felt uneasy about their future prospects. Britain’s vote for Brexit and the election of Donald Trump as president of the United States were perceived as a decisive rejection of the liberal elite and its ethos.

The current form of the anti-populist narrative should be interpreted as a sublimated critique of popular sovereignty and democratic decision-making

It is our belief that the Western liberal elite’s irrational hatred of Hungary’s political culture is driven by a deeply entrenched sense of insecurity regarding its own legitimacy. The current form of the anti-populist narrative should be interpreted as a sublimated critique of popular sovereignty and democratic decision-making. In recent years, sections of the Western political class have become disconcerted by the outcome of elections and referenda. In some cases, their disappointment with their own capability to motivate and influence the electorate has crystallized into an anti-democratic sensibility towards public life. For example, James Traub, an American critic of the ‘illiberal democracy’ prevailing in Hungary, sounds distinctly illiberal in his condemnation of the people who voted for causes he dislikes. In an essay titled ‘It’s Time for the Elites to Rise Up Against the Ignorant Masses’, Traub asserted that what developments such as Britain’s vote for Brexit indicate is that the ‘political schism of our time’ is not between left and right but ‘the sane vs the mindless angry’.5 He regards the ‘ignorant masses’ as his moral inferiors who need to be re-educated by the enlightened elites. He commented, ‘Did I say “ignorant”? Yes, I did. It is necessary to say that people are deluded and that the task of leadership is to un-delude them.’6 The conviction that the people of Hungary who support the wrong kind of political movements are ignorant and stupid allows Traub to adopt a paternalistic tone that is usually associated with the authoritarian elitism he decries.

The intemperate language adopted by anti-populist polemicists is underwritten by a disturbing tendency to regard democracy as a mixed blessing. They do not simply blame people for voting the wrong way or voting against their interests, but also accuse sections of the electorate of lacking the moral and intellectual resources necessary for acting as responsible citizens. Such pessimistic assessments of the capacity of the people to vote the right way have led to the questioning of the value of democracy itself.7 It seems that some anti-populists are far more interested in de-legitimizing the moral status of their opponents than in attempting to understand their own responsibility for the setbacks suffered by liberalism.

When you scratch the surface it becomes evident that elite hysteria regarding the threat of populism is animated by its distaste for the people and hatred for democracy. As I discussed in my book, Democracy under Siege: Don’t Let Them Lock It Down,8 ‘Demophobia’, or the fear of the people, has acquired a pathological form in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump. Since that time, sections of the Western elite have become habituated to using words like ‘fascist’, ‘authoritarian’, ‘illiberal’, and ‘anti- democratic’ as interchangeable with populism.

Populism is invariably represented as a threat to democracy, yet at the same time the reaction to it is animated by a powerful mood of suspicion towards democracy. The real reason why they despise populism is not because it is a threat to democracy, but because people who support it reject the moral authority of a failed political establishment. Populist movements believe that decisions should reflect the will of the people and not the outlook of experts and technocrats.

The current wave of anti-populist and anti-democratic literature is underpinned by a profound sense of anxiety about the loss of elite authority. Yet its authors find it difficult to openly acknowledge the fact that the authority of political order that prevailed in the West during the Cold War has gradually unravelled. The ‘crisis of liberalism’ literature rarely interrogates itself to ask why representatives of the political establishment struggle to challenge and neutralize the appeal of its populist opponents. Instead of exploring the implications of the loss of its authority it prefers to point the finger of blame elsewhere. Unable to face up to their crisis of authority, anti-populist ideologues blame their inability to win the arguments on the moral deficiencies of voters, who are spontaneously drawn towards the supposedly simplistic ideas of their opponents. Jason Stanley, in his book How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them (2018) notes that ‘the pull of fascist politics is powerful’ because it ‘simplifies human existence’.9 Instead of raising concern about the poverty of the intellectual outlook of those opposed to populists, Stanley prefers to point the finger of blame at an unsophisticated public who are moved by the simplistic message of the fascists. In passing, it is important to point out the unceasing allusions to the threat of fascism, which has become a constant theme promoted by anti-populists. Torn from its historical context, the term fascism has been emptied of its precise historical meaning. It serves as a term of abuse to be hurled at political opponents.

Jason Stanley’s dishonest coupling of populism with fascism offers a paradigmatic illustration of how elite hysteria now works as a medium of academic analysis. In Stanley’s fantasy world, America is in ‘fascism’s legal phase’ and supposedly authoritarian leaders like Viktor Orbán are following the screenplay of interwar fascists.10 He wrote:

‘Fascist ideology strictly enforces gender roles and restricts the freedom of women. For fascists, it is part of their commitment to a supposed “natural order” where men are on top. It is also integral to the broader fascist strategy of winning over social conservatives who might otherwise be unhappy with the endemic corruption of fascist rule. Far-right authoritarian leaders across the world, such as Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, and Russia’s Vladimir Putin, have targeted “gender ideology”, as Nazism targeted feminism. Freedom to choose one’s role in society, when it goes against a supposed “natural order”, is a kind of freedom fascism has always opposed.’11

Stanley’s takeaway message is that governments who oppose the ideology of gender neutrality are simply following the ‘fascist strategy of winning over social conservatives’.

In his heart of hearts he understands that millions of people throughout the world are profoundly hostile to gender ideology. The vast majority of people throughout the world are thoroughly opposed to transgenderist ideology. For very good reason! Throughout history the biological distinction between male and female and the conviction that these were the only two biological sexes served as a scientifically validated fact of life. Yet today, such beliefs are indicted as markers for authoritarian fascism! No wonder the crusade against populism appears to be increasingly driven by a moral panic.

It is worth noting that since the outbreak of the COVID pandemic, anxiety about the workings of democracy has mutated into a veritable politics of hysteria. In recent times, populism has sometimes been portrayed as a virus that is no less of a threat than COVID-19. Australian Labour politician Andrew Leigh’s book, Existential Risk and Extreme Politics, is paradigmatic in this respect. Leigh claims that existential threats like climate change, pandemics, and nuclear war are not unlike the threat posed by populist adversaries. In this scenario populism works as a destructive virus with a fascist face!

A Distorted View of Populism

Twenty-first-century liberals often regard the ‘forces of populism’ as their bitter foes. Yet it is far from evident what they mean by the term populists. The usage of the term populism to explain contemporary issues is devoid of conceptual clarity. The application of a single term to account for movements of both the far left and the far right, as well as those without any clear ideological attachments, and to the governments of Venezuela, Turkey, Russia, Poland, or Hungary, lacks conceptual clarity. Populism is increasingly used as a moral category in order to condemn and devalue its target. Today, populism is a term that anti-populists use to describe people, who hold wrong ideas.

The meaning of twenty-first-century populism is fraught with difficulty because its usage has been heavily influenced by the anti-populist temper that dominates public discourse

The meaning of twenty-first-century populism is fraught with difficulty because its usage has been heavily influenced by the anti-populist temper that dominates public discourse. In the past, populism served as a form of self-designation and people knowingly described themselves using the term. During the nineteenth century, the Narodniks in Russia, like the People’s Party in the United States, took pride in their populist outlook. In the twenty-first century it is the advocates of anti-populism who define their opponents as populist. The political scientist Ivan Krastev raised an important question when he asked ‘who decides which policies are “populist” and which are “sound”?’12 In the contemporary era, this decision has become the prerogative of a coterie of influential anti-populists.

In the twenty-first century the meaning of populism has been distorted through the tendency of its opponents to attribute a wide range of negative qualities to it. The academic literature on populism is typically hostile to its subject matter and often projects values and attitudes onto movements which its members would not recognize as their own. For example, a book on The Politics of Fear associates populist ‘EU-scepticism’ with a ‘chauvinist, nativist view of “the people”’ and with an extreme right-wing orientation.13 This coupling of extreme right-wing inclinations with Euro-scepticism is no doubt an outcome of a genuine incomprehension of the phenomenon, but it also distorts a reality where the aspiration for democracy and solidarity has left millions of people disillusioned with the EU.

In the twenty-first century, the main distinguishing feature of movements labelled as populists is their tendency to challenge the cultural values espoused by the political establishment. As the political theorist Margaret Canovan pointed out, unlike so-called social movements, populism does not merely challenge the holder of power, but also ‘elite values’. Therefore, its hostility is also directed at ‘opinion formers and the media’.14 Often the challenge posed by populist movements to elite values is expressed through their reluctance to abandon customs and traditions that elites have discarded: sentiments described by the use of that confusing term ‘nostalgia’.

Many of the reactions and attitudes associated with populism constitute what the political philosopher Hannah Arendt would have characterized as the search for pre-political authority. The common quest for gaining meaning through the forging of pre-political solidarity can often express itself in affirming traditional family and community life, religion, and solidarity. This attempt to re-appropriate morality goes directly against the grain of the cultural norms that prevail in the West.

Hungary and the Problem of Political Language

The language through which the political situation in Hungary is framed does little to illuminate events. In the Hungarian context, political debate is often described as a clash between the right-wing, populist government of Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz and his ‘leftist’ and ‘liberal’ opponents. Whatever these labels mean, they have little in common with the classical usage of these terms. The political outlook of Fidesz is best described as a synthesis of conservative nationalism and Christian democracy. Given that it seeks to address the people of Hungary, its politics contains an important plebeian dimension. However, though Fidesz criticizes neoliberal and EU elites, it is not strictly speaking against elites as such. Within the Hungarian vernacular, Fidesz is best described as a polgári party. In Hungarian, the word polgári encompasses civil, citizen, and bourgeois, and it is the middle-class bourgeois citizen who constitutes the imagined audience of Fidesz.

One possible reason why foreign critics of Hungary fail to characterize the politics of the government accurately is possibly because they very rarely encounter traditional conservatives in their own societies. Most parties that are associated with conservatism in Western Europe—such as the British Tories or the German Christian Democrats—have become estranged from the traditional values of their movement. Back in the 1970s they still self-consciously promoted traditional conservative values, and frequently argued for going back to basics. Going back to basics meant upholding the traditional family, affirming religious morality, and loyalty to the nation. As a result of the setbacks suffered in the culture wars, Western European conservatives went on the defensive and became hesitant about arguing for traditional values.15 That is why periodic attempts to relaunch the conservative project often ended with a plea to get rid of the old ideological baggage and to modernize.

In contrast to so-called modernizing Western conservatives, Hungary’s Fidesz government is unapologetically traditional.

Its celebration of religion, the traditional family, and patriotism echoes the narrative that European conservative parties actively promoted as late as the 1970s. That is why— unlike Western conservative parties—they are unashamedly right-wing. Whereas Western- European conservatives are reluctant to call themselves right-wing, their Hungarian and Eastern European counterparts have no inhibitions on this score.

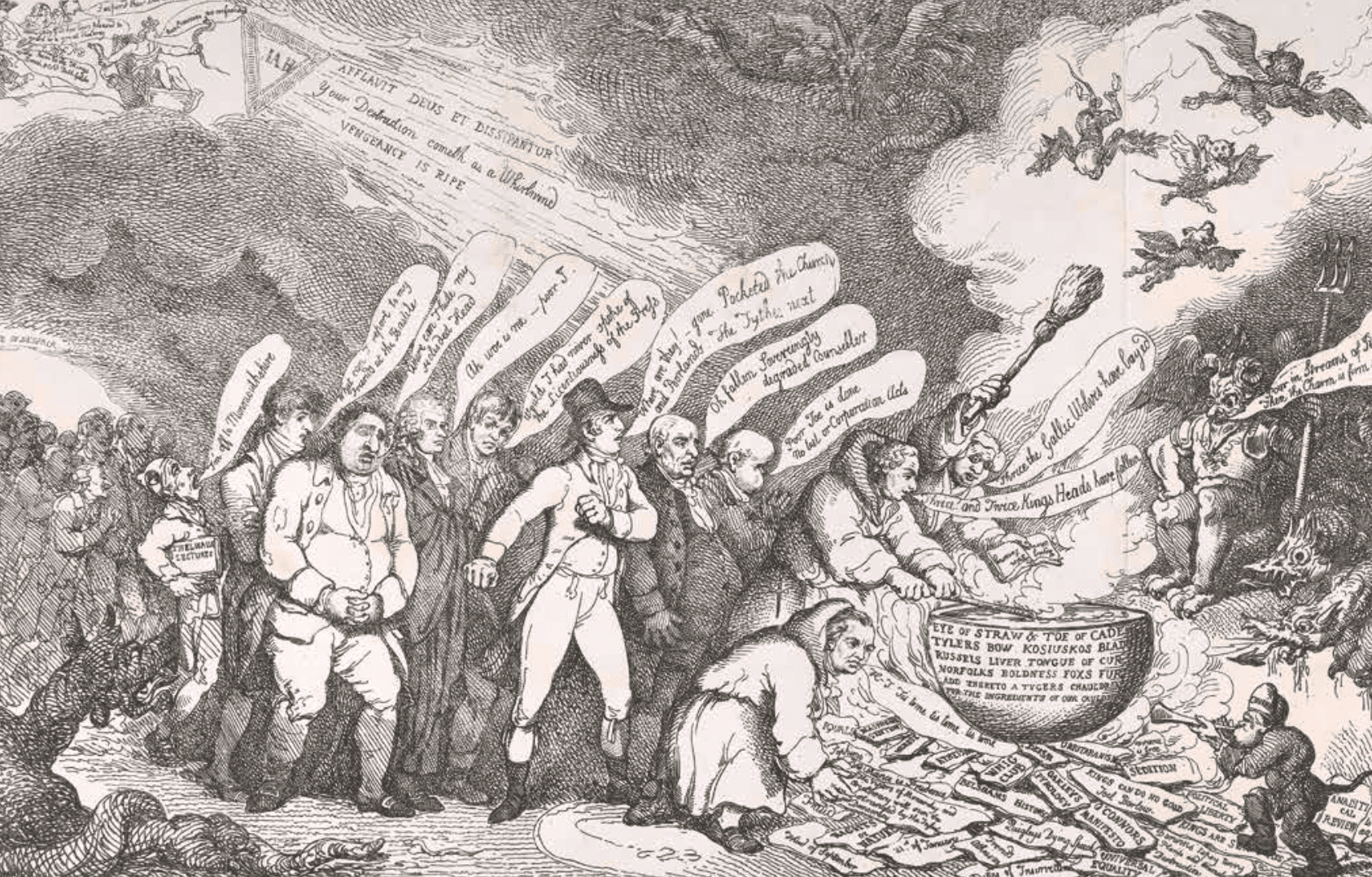

Recently, Jonathan Freedland, a leading columnist for The Guardian, reflected on the theme of populism as virus. He ended his article with the words, ‘Brexit is the virus. Boris Johnson was only ever its most visible carrier.’ Of course, the virus that Freedland dislikes is the virus of democracy. He is by no means the first individual to associate democracy with a virus. Indeed, historically, the fear of democracy was most strikingly expressed through its description as a deathly virus. In 1841, drawing attention to this supposed perilous disease, the Reverend Joshua Brooks noted that, ‘we have already seen France, Belgium, Italy, Poland, and other places, affected by the revolutionary spirit’, the chief incitement to which is the democratic virus!16 Thankfully, democracy has proved infectious. Without the infectious quality of democracy, regime change in Hungary, Poland, and other parts of Central and Eastern Europe would never have occurred.

Those who wish to put populism in chains hope to ensure that the democratic virus is placed under quarantine. To achieve this objective, Hungary must be taught a lesson and the technocratic woke consensus promoted by the American State Department and the EU bureaucracy must prevail. For the Western cultural elites, acceptance of its woke values is non-negotiable. Their culture war has gone global, and from their perspective Hungary must be taught a lesson. That is why the outcome of the April election is not just about the future of Hungary, but also about the soul of Europe.

NOTES

1 www.politico.eu/article/meps-call-for-full-scale- election-observation-in-hungary/.

2 www.euractiv.com/section/digital/news/eu-funds- fact-checking-website-in-hungary-ahead-of-crucial- elections/.

3 https://twitter.com/lisanandy/ status/1397895918498758660.

4 www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-01-21/ why-a-vote-on-orban-s-rule-reverberates-across- europe-quicktake.

5 James Traub, ‘It’s Time for the Elites to Rise Up Against the Ignorant Masses’, Foreign Policy (28 June 2016).

6 Traub, ‘It’s Time for the Elites to Rise Up’.

7 See for example J. Brenan, Against Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016).

8 www.amazon.co.uk/Democracy-Under-Siege Dont-Them/dp/1789046289/ref=sr_1_2?crid=2B-B5L5EBMLJK9&keywords=frank+furedi+ democracy&qid=1642502900&s=books& sprefix=frank+furedi+democracy% 2Cstripbooks%2C51&sr=1-2.

9 Jason Stanley, How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them (London: Penguin, 2018), xii.

10 www.theguardian.com/world/2021/dec/22/ america-fascism-legal-phase.

11 www.theguardian.com/world/2021/dec/22/ america-fascism-legal-phase.

12 Alan McPherson and Ivan Krastev, eds, The Anti-American Century (CEU Press, 2007).

13 See R. Wodak, The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean (London: Sage, 2015), 41–43, 54–55.

14 Margaret Canovan, ‘Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy’, Political Studies, 47/1 (1999), 2–16.

15 I discuss the defeat of conservative values in the culture war in my book First World War: Still No End in Sight (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), Chapter 6.

16 Joshua William Brooks, Essays on the Advent and Kingdom of Christ: And the Events Connected Therewith, (1840), 29, https://books.google.hu/ books?id=2wQ3AAAAMAAJ&pg=RA2- PA29&lpg=RA2-PA29&dq=joshua+brooks+we+ have+seen+France,+Belgium,+Italy,+Poland,+and+other+places,+affected+by+the+ revolutionary+spirit&source=bl&ots=bPyxt- Ga4ZG&sig=ACfU3U2iaWjEVW7fvsFLIL3Zl- b8Q5b8LRg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwirxp- 3d1P_1AhUO7qQKHakyAcYQ6AF6BAgmEAM#v= onepage&q=joshua%20brooks%20we%20have%20 seen%20France%2C%20Belgium%2C%20Italy%2C% 20Poland%2C%20and%20other%20places%2C% 20affected%20by%20the%20revolutionary%20 spirit&f=false.