This article was published in Vol. 4 No. 2 of our print edition.

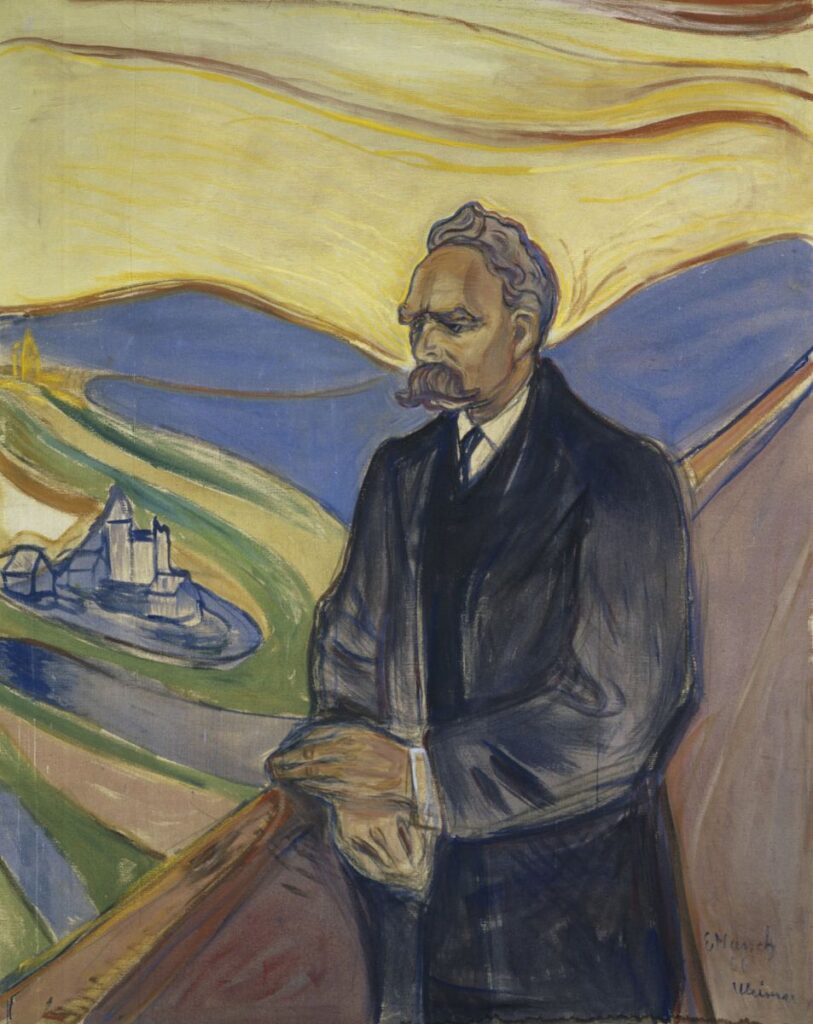

Nothing new happened in 2023. The struggle continues and anxiety remains constant. If there is any one thing that warrants attention, it is that the war in Ukraine, which has been set up as an existential issue, cannot be won by the West.1 It may be seen as boring to write about crisis, as it has been endlessly discussed over the last two centuries or more, but it can still be real. In recent decades, the number of books on the crisis of modernity, liberalism, or the West has perhaps been exceeded only by films on such topics. The concept of crisis has been with us at least since the French Revolution, but during the nineteenth century, it was more closely associated with the optimism inherited from the eighteenth century: utopias, redemptive (political) religions, and faith in progress and human reason dominated Europe. This optimism permeated the works of even the most critical thinkers on the topic of Europe, such as Marx and Nietzsche. Both thought they saw the solution, one in communism, the other in the coming of the Übermensch. Liberalism, like Nazism and socialism, believed in the perfectibility of social life and the existence of a final state—what Fukuyama called liberal democracy—towards which humanity is necessarily moving.2

This optimism, mixed with a sense of crisis, turned to pessimism even before the First World War, as exemplified by the works of Max Weber and Oswald Spengler.3 This pessimistic sense of crisis characterized the twentieth century, as it continues to do in our own day. However much Spengler’s contemporaries mocked him, pointing out the prosperity of the West, and the attractiveness of its liberal democracy, not long after he finished writing The Decline of the West, the nations of the West went to war with each other once again, and peace was only ultimately brought to Europe by two ideological empires located on its periphery. Both the United States and the Soviet Union were ideological states, established on an ideological basis, with both ideologies originating from, and indeed being mutations of, European culture. Les Trente Glorieuses were overshadowed by the possibility of nuclear war and the occupation of Europe by these two extra-European superpowers, albeit both with a partially European culture. Since then—or until today’s Facebook-world—Europe has been granted a seductively pleasant and prosperous existence in exchange for the loss of its independence. The two ruling superpowers still retained the optimism of the nineteenth century, partly as a means of defeating the other: if only the rival ideology and the empire it birthed and maintained were to fall, then humanity’s age of happiness would dawn.4 At the level of ideological geopolitics, each used an equivalent justification to that employed by Georges Sorel5 with regard to domestic politics, to justify the use of violence: the source of our problems is a social group, a way of thinking, which, if eradicated—by cutting out the rot—would leave society pure and healthy. Sorel and this way of thinking have had many supporters over the last hundred years, among whom the best known may have been Lenin and Mussolini.

The struggle between the two non-European empires ended for a time around 1990, which is when perhaps the most optimistic strand of modern thinking emerged, naturally from the pen of the victors: liberal democracy had won, and from now on we would face only local, manageable problems. Although this victory was indeed followed by twenty-five years of true hegemony, and a spirit of triumphant optimism was palpable at times,6 mass culture was dominated by dystopias and disaster stories. As Habermas put it, utopian hopes had been exhausted,7 so what remained was terror. The global liberal elite is old: ‘They’re tired. They’re scared. And they should be. Their time is up.’8 In other words, the fearful liberalism described by Judith Shklar9 does not even try to formulate a hopeful vision of the future with which to mobilize voters, but instead attempts to rally support by painting terrifying visions of potential future alternatives: this could be COVID, or some other kind of pandemic, or an apocalypse resulting from climate change (net zero), or the lack of freedom (called an authoritarian system, populism), or simply Putin; supposedly the only alternative to Western liberal oligarchs is electoral or democratic autocracy.

Liberal democracy is ‘liberal’ because it grants certain established minorities special protection against the majority. Oligarchy means rule by a privileged but not exceptional minority. Just as progressives once considered limiting the freedom of morally and/or intellectually suspect individuals who sought to slow the unstoppable march of progress—in short, reactionaries—now they seek limit the freedom of all opponents, citing these terrifying dangers.

Europe’s Geopolitical Insignificance Has Gone Hand in Hand with Its Economic and Social Crisis

The peace and economy of Europe was maintained by the Pax Americana, which is now falling apart for economic and military reasons. During the Vietnam War, it became clear that the enlisted American citizen did not want to fight, and neither now does the European. Europe has lost its industry, does not want to protect its borders, and its citizens demand through their votes that the state free them from the necessity of performing difficult and low-prestige jobs: industry has been relocated to Asia, while poorly paid, low-prestige service and construction jobs—which cannot be outsourced—are carried out by non-citizen immigrants. Countless studies have been made of the relative decline of the European economy, average incomes, and quality of life over the past fifteen to twenty years.

The disintegration of the Pax Americana stems from the internal problems of the West,10 as a result of which more and more countries have become strong enough to resist the imperial will. On the surface, the events of today bear a striking resemblance to the collapse of the Delian League. Notably, Athens, the ancient analogue of today’s democracies and ultimate loser of the struggle, uses amoral, realist reasoning in the Melian Dialogue.11

As Liberal Democracy Has Weakened, So Has the Geopolitical Position of the West

The oldest and most visible crisis is the demographic one, to which the attempted response is immigration combined with accusations of Islamophobia. The resulting diversity regime,12 a kind of asymmetric multiculturalism, is the elite’s answer to the problem of hyperpluralism: how to control a mass of people with endlessly diverse views, among whom there is no chance of forming a consensus or a stable majority. Asymmetrical multiculturalism, while proclaiming the equality of all cultures, is in practice based on the fact that the cultures of some recognized religious, ethnic, and lifestyle minorities are worthy of support and respect, while the local—European and Christian—culture must admit its past corruption and sins in order to be purified. Its identity and traditions must likewise be rejected, as there is nothing worthy of respect in them. The middle class is fleeing the big cities because in addition to underclass districts that do not respect the law, ethnic and religious ghettos that also reject the law have been created. At the same time, the middle class is slipping further and further from prosperity, and its distance from the elite is increasing. Partly due to economic problems and partly due to cultural disintegration, the willingness of citizens to cooperate is decreasing, so Western states feel obliged to increase direct and indirect control.13 The dreaded themes of liberalism serve to justify this. Today’s name for this Orwellian consciousness-formation and violent ideology propagation is ‘Woke’, which promises the usual liberation—though this time, paradoxically, from the world created by previous generations of liberal democrats. And its tools are universities, the media, and big tech companies.

‘The oldest and most visible crisis is the demographic one, to which the attempted response is immigration’

Mass illegal migration is in the interests of many in the West: the oligarchs (who need the workforce), the upper middle class (who need the cheap services), and the left (who have run out of voters and want to make up for the deficit by importing them).14 The dissatisfaction stemming from the above has increasingly turned Western peoples against the global liberal elite, as expressed in the rejection of globalization, Wokery, multiculturalism, and the global free market. The liberal elite has called these people ‘disaffected populists’,15 if not something much worse, and is responding to them in illiberal, freedom-restricting ways, such as the proceedings against Trump, or Donald Tusk’s coup attempt in Poland, and at times with blackmail.16 These actions of the international liberals are nothing more than attempts to restore the ancien régime of the globalist elite. Behind references to the norms of the rule of law there is nothing but the assertion of power interests, and an effort to preserve the status quo at all costs. They want to protect the normativity of the old order by pushing aside all norms: the status quo does not require justification; it is self-evident.

Nihilism

It has long been suggested that the European crisis has its roots in cultural or even religious sources. Ever since Rousseau’s Social Contract,17 a great mass of Europeans wanted to establish a new religion, ideology, or trend that promised some solution. The result of their scramble was that the various teachings, improvised before our very eyes, mutually cancelled out or relativized each other. At the beginning of the twentieth century, in contrast to the Christian outlook that promoted work, study, diligence, self-discipline, and moral and practical excellence, which once made the West great, there spread instead an all-pervading nihilism, as described at almost the same time by Marx18 and Dostoyevsky,19 before Nietzsche raised it to the level of philosophy.

According to the proud self-image of capitalism, it engaged in what Schumpeter called ‘creative destruction’, and the cultural revolutionaries have likewise striven after the same thing. However, while in economic terms there truly was creation as well as destruction, in a cultural sense only destruction could be discerned, due to the overproduction of isms. Competing explanations of reality extinguished one another’s credibility, and the West entered an age of ‘warrior gods’. The arrival of this age was presaged by the disillusionment and pessimism of the late nineteenth century, which continues to characterize our own time.

In this fin de siècle atmosphere, two forms of nihilism emerged, one characteristic of the manager–bureaucrat ruling elite, the other the bohemian nihilism of the governed. They had in common a generalized suspicion of the moral and religious principles and strictures handed down by tradition, and, more broadly, an absence of positive values. Nihilism is very appealing and alluring, as it frees the individual from various limitations. What is more, its long-term consequences are only felt later, when those who adopted it are no longer in charge. The first iteration was represented by Nietzsche, the second by Foucault. In the closing lines of one of his most insightful texts, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Weber writes about the disappearance of the way of life and mentality that made the West great. The self-discipline (asceticism) that created the success of the West is being replaced by amoral utilitarianism, and the age of the last people is coming: ‘specialists without spirit, sensualists without heart; this nullity imagines that it has attained a level of civilization never before achieved.’20 The sentence is presented by Weber as a quotation, though it is not known exactly of whom; the most likely candidate is Gustav Schmoller.21

Nietzsche’s Übermensch is beyond the moral categories of good and evil; they do not apply to him, and he cannot be judged by them, nor does he himself make judgments based upon them. The nihilism of the elite was called neutrality, or rationality. Burnham, for example, referred to them the new Machiavellians: ‘No theory, no promises, no morality, no amount of good will, no religion will restrain power…Only power restrains power.’22 The point is that the usual, familiar, expected, broadly observed moral standards do not apply to them. Their actions are free from those restrictions. Power is free from moral restraints and the elite has power. However, the (current) left-wing positivism of the bureaucratic elite is not the only version of elite nihilism. The more belligerent version of elite nihilism, heroic nihilism, is older and also well known, and likewise places itself beyond good and evil. It is no coincidence that the postmodern left rediscovered Carl Schmitt and made him a widely recognized author, particularly on account of his work The Concept of the Political, which radically separates political action from moral expectations. The political concept of this postmodern left has thus become agonism, according to which, in the power struggle, nothing matters except who hits harder. The dilemma of ‘dirty hands’ does not even arise for those who are above morality.23 The ‘dirty hands’ dilemma presupposes that the political actor accepts the existence of norms beyond his or her control, and also recognizes that the action deemed necessary contradicts them. Such an actor pays for political effectiveness with a guilty conscience, a theme in Shakespeare’s Henry VI:

Why, then, I do but dream on sovereignty

Like one that stands upon a promontory

And spies a far-off shore where he would tread,

Wishing his foot were equal with his eye,

And chides the sea that sunders him from thence, Saying he’ll lade it dry to have his way.

So do I wish the crown, being so far off,

And so I chide the means that keeps me from it,

And so, I say, I’ll cut the causes off,

Flattering me with impossibilities.

My eye’s too quick, my heart o’erweens too much, Unless my hand and strength could equal them...

And, whiles I live, t’ account this world but hell Until my misshaped trunk that bears this head Be round impalèd with a glorious crown.

And yet I know not how to get the crown, For many lives stand between me and home;…

I’ll play the orator as well as Nestor, Deceive more slyly than Ulysses could, And, like a Sinon, take another Troy. I can add colours to the chameleon,

Change shapes with Proteus for advantages, And set the murderous Machiavel to school. Can I do this and cannot get a crown?

Tut, were it farther off, I’ll pluck it down.24

Of course, it has been true throughout history that the holders of power, or those who aspire to hold it, welcome thinking that frees them from moral limitations, from Marsilius of Padua to Machiavelli, and from Nietzsche to postmodernism. Nothing, besides perhaps another, external power, limits one’s desires and ambitions. The elite is a power elite: it has no limits. And one who wields such power can disregard moral claims because they are claims made upon the basis of rival power, and as such are not to be considered, but merely overcome. At the same time, few eras in history have felt more need to moralize—i.e. to try to justify their right to rule by moral arguments—than the age of democracy. Hypocrisy is the normal method of the democratic elite,25 the experience of which only strengthens the tendency of those living within a democracy towards nihilism.

The embodiment of bohemian, popular nihilism is the hedonist, and the ideologist of this perspective is Foucault, who is himself entirely fixated on power, but in a different way than the elite nihilists described above. Alongside hedonism, it is characterized by the rejection of reality, as well as various forms of self-destruction (abortion, euthanasia, drugs). This form of nihilism can only be afforded by those living in great prosperity—such as the citizens of Western liberal democracies—while elite nihilism has a much longer history. It is rarely called nihilism, but more often referred to as hedonism, consumerism, or perhaps left-libertarianism, and is typically associated with democracy. Before Woke took off around 2010–2012, Gerhard Schulze called this nihilism characteristic of today’s West the ‘experience society’.26 But its apologists also call it the ‘aesthetic self-creation’ of the self, following Foucault, who called the lifestyle it represents the ‘ethics of pleasure’.27 Perhaps the very first description of them is to be found in Plato’s Republic, where they are referred to as lotus-eaters: people who live only for pleasure are characteristic of both democracy and tyranny.

The terms Genußmenschen or Erlebnisgesellschaft (‘people of pleasure’ and ‘experience society’) designate precisely what the term lotus-eater meant to Plato: it is a seductively pleasant way of life, and its ideologues to this day sneer at criticism. While elite nihilism frees political actors from normative constraints and expectations—at most tolerating what the political actors themselves create, such as the political religions and ideologies of modernity—Foucault would free the bohemians from all kinds of normative expectations. The first would make power unlimited, the latter would abolish all power. The basic idea is that normative expectations must in all circumstances be avoided, and continuously resisted and deconstructed, otherwise an oppressive regime of new norms will take over.

This nihilism is called ‘liberal’ because it extends the freedom and enjoyment of choice to everything: not only to desire but also to the self and even to the environment in which the self lives. Bohemians can not only create their own selves ‘freely’, but also their relationships and environment. In opposition to Nietzsche, Foucault continued Fourier’s anarchist thinking: in Discipline and Punish, he argues that to reject the idea of the criminal is to reject justice and the law. The criminal is a heroic resister. The normativity of Foucault’s bohemian nihilism can be grasped in this anarchism: all expectations are oppressive. The law is oppression, and decriminalization brings freedom. And he never explores whether there should be limits to decriminalization: should it also cover crimes against life?

According to Foucault, there can be no doubt that power is concentrated in the state, but it is not enough to weaken or eliminate the state because power also exists in interpersonal relationships in the form of normative expectations. No matter what we do, this pattern reproduces itself, so all forms of normalization must be continually resisted. He criticizes the Enlightenment and liberalism because these ostensibly free people and increase freedom, but in reality put chains on them (from which it follows that freedom and chains are real, so reality exists), whereas Nietzsche took precisely the opposite view. While for the last hundred years, we have debated whether the Protestant ethic or other religious teachings played a role in the creation of the mentality that made the West great, we must now come to terms with the fact that the disappearance of this mentality was accompanied by the disappearance of religion. Weber and his contemporaries experienced the beginning of this process, and later generations saw its consequences: totalitarian and then bohemian nihilism. We have all heard it said that there is no such thing as a free lunch; we have also heard that Westerners can be freed from the consciousness of limitations, and can boldly set out to finally take their destiny and history into their own hands. But this has been achieved with about as much efficiency as Oedipus. And supporters and champions of emancipation, both past and present, do not talk about the price of these liberating efforts.

The first great wave of modernist liberation, which continues to this day, was directed against religion, and chiefly against Christianity. As Mircea Eliade described it: ‘it is only in the modern societies of the West that nonreligious man has developed fully. Modern nonreligious man assumes a new existential situation; he regards himself solely as the subject and agent of history, and he refuses all appeal to transcendence…Man makes himself, and he only makes himself completely in proportion as he desacralizes himself and the world. The sacred is the prime obstacle to his freedom. He will become himself only when he is totally demysticized. He will not be truly free until he has killed the last god…To acquire a world of his own, he has desacralized the world in which his ancestors lived.’28

‘The West, seeking liberation, first killed the king, then God, then the father, and now nature’

However, the Holocaust and the Gulag sharply raised the problem of modernity: ‘ this is indeed the question: whether men can acquire the knowledge of the good, without which they cannot guide their lives individually and collectively, by the unaided efforts of their reason, or whether they are dependent for that knowledge I on divine revelation.

The West, seeking liberation, first killed the king, then God, then the father, and now nature, in order to remove these uncomfortable limitations. However, this liberation could only be enjoyed so long as the majority—despite all kinds of intellectual hand wringing—accepted limitations, tried to meet expectations, and did not see either norms or responsibilities as mere tricks of oppression. The experience of these modernist experiments has been that whenever the revolutionaries or reformers found they could not replace Christian religion with a new normative order, they resorted to violence. Whatever the world’s ideologues say, a world without normative order is neither pleasant for those who live in it, nor even in the long run a functioning system.

So What?

Fifty years ago, Daniel Bell already stated that the capitalist economy, the modern West, would require the disciplined worldview described by Weber, whereas mass culture promotes a bohemian approach—the worldview of 1968—that is its precise opposite.29 Western society treated these criticisms much like the proverbial man who falls from a tenth story window and, as he falls, says ‘so far, so good’. Now, however, we can see that many things are going wrong, from demographics and family to the desire to learn, the desire to work and, where appropriate, even to defend one’s country. Western societies have obliged their governments to create for their citizens the maximum possible number of bullshit jobs, in which there are no tangible performance metrics, and to free them from any remaining institutional authorities such as family, church, and school. Thus, in general, from all moral and practical expectations.

The West has increasingly attempted to solve its demographic problems through migration, hoping that those coming from distant lands would assimilate to the attractive Western lifestyle. And it happened. In liberal democracies, an ethnic working class has emerged in a surprising way: the workers increasingly have a different language, skin colour, and religion to that of the elite in a particular country—a common enough phenomenon in antiquity and the Middle Ages, but a difficult one to square with the self-image of liberal democracy.

However, the West needs people who try to meet expectations, who discipline themselves, study, work, raise children and, if necessary, defend the political community. Immigrants who align themselves with expressive individualists or self-creating egos—or any of the countless other terms used to describe popular bohemian nihilism—helped mask the West’s problems for at least a generation, but today they are no longer helping, because they had already adopted elements of the Western way of life through global media before they arrived. Who will work, study, and care for the old and sick, give birth and raise children, and defend the country? For many decades, the West has only been able to survive by constantly needing people who do not, or at least only partially, live according to the ethos of Western nihilism: they give birth and raise children, can postpone the satisfaction of their desires, and discipline themselves. The West has not responded to the problem of a sustainable society, even though its problems are more acute than those of the environment.

Although Schadenfreude Tastes Sweet, There Is No Cause for It Because Hungary Is Also Part of the West

Rebellion against liberal oligarchy offers no alternative to nihilism. Westerners love their way of life, and at best are now angry with the liberal oligarchy because that way of life seems to be over for many. The anti-liberal movements that appeared during the twentieth century were even more nihilistic,30 and at times violent, than the liberalism they sought to replace, but they did not want to return to the culture on which the success of the West was based. And just as liberalism did not succeed in transforming people after socialism, neither did the competing anti-liberal, post-Christian, nihilistic trends. The solution is certainly not political or movement-based: those had already failed by the middle of the twentieth century.

The situation offers few grounds for optimism. Those brave enough to face the liberal oligarchy, if they wish to be successful, seem compelled to accept and use both versions of nihilism to their advantage. And so Henri Brisson’s slogan remains useful: Pas d’ennemis à gauche (no enemies to the left).

The reaction of the right, tired of the neo-Kantian moralizing hypocrisy of liberal politics, is understandable: today’s cult of Schmitt liberates political action from moral constraints, just as Richard III freed himself from his conscience. The other reaction is to tinker with ideology. Let us have our own principles, morals, flag, identity, and so on. If nihilism contains attractive elements for the political actor, ideology is also suitable for the continuous mobilization of voters on behalf of some project of social engineering. For the manager-bureaucrat elite, both solutions contain attractive elements.

The third option involves the most problems: compliance with the inherited and familiar norms. Not merely observing them, but piously accepting their limits—and fighting only against opponents. Since no one likes to fight with one hand tied behind his back, this third option is not popular in practice, either in high or low politics.

Translated by Thomas Sneddon

NOTES

1 Emmanuel Todd, La Défaite de l’Occident (The Defeat of the West), (Gallimard, 2024).

2 See: John Gray, The Two Faces of Liberalism (Polity Press, 2000).

3 Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West, trans. Charles Francis Atkinson (Oxford University Press, 1991).

4 Hegelian Stalinist Alexandre Kojève called this the ‘universal and homogenous state’, and Fukuyama took his thesis of the end of history from him, but the latter took it to mean the victory of the American empire. See: Leo Strauss, On Tyranny (University of Chicago Press, 2000).

5 Georges Sorel, Sorel: Reflections on Violence (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

6 Steven Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (Penguin Books, 2012); Jeremy Rifkind, The European Dream (Tarcher, 2004); Thomas Roy Reid, The United States of Europe: The New Superpower and the End of American Supremacy (Penguin, 2005); Daron Acemoglu, and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (Crown Currency, 2013).

7 Jürgen Habermas, ‘The New Obscurity: The Crisis of the Welfare State and the Exhaustion of Utopian Energies’, trans. Phillip Jacobs, Philosophy & Social Criticism, 11/2 (1986), 1–18.

8 Kevin Roberts, ‘What I Learned at Davos: The Future of Democracy Is Secure’, The National Interest (29 January 2024), https://nationalinterest.org/feature/what-i-learned-davos-future-democracy-secure-208938.

9 Judith Shklar, ‘The Liberalism of Fear’, in Nancy L. Rosenblum (ed.), Liberalism and the Moral Life (Harvard University Press, 1989).

10 Todd, La Défaite de l’Occident; Douglas Murray, The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity, Islam (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017).

11 Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War (Oxford University Press, 2009).

12 Ben Cobley, The Tribe: The Liberal-Left and the System of Diversity (Imprint Academic, 2018).

13 Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (Profile Books, 2019).

14 In English-speaking countries, left-wing parties propose extending voting rights to illegal migrants—that is, to non-citizens.

15 Michel Geoffroy, La Super-Classe Mondiale contre les Peuples (The Global Super-Elite vs. the People), (Via Romana), 2018.

16 See: Grace Melton, ‘If You Want Our Help, You Must Accept Our Gender Ideology’, The Heritage Foundation (16 February 2023), www.heritage.org/gender/commentary/if-you-want-our-help-you-must-accept-our-gender-ideology;

‘At the same time, around EUR 20 billion remain frozen. They are suspended for reasons that include concerns on LGBTIQ rights, academic freedom and asylum rights. Some are blocked under the conditionality mechanism. And they will remain blocked until Hungary fulfils all the necessary conditions.’ Speech by President von der Leyen at the European Parliament Plenary on the conclusions of the European Council meeting of 14–15 December 2023, https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/news/speech-president-von-der-leyen-european-parliament-plenary-conclusions-european-council-meeting-14-2024-01-17_en.

It is difficult to say whether in the global culture war and the enforcement of Woke, gender, and LGBTQ ideology, the ideology is merely a moral justification for the regulation and control of the imperial periphery, or whether they really wish to implement an ideological order. It is probably both. Coincidentally, it seems that the moral self-confidence of the West today is derived from the spread of Wokery (as formerly from the export of democracy). But it may also be that they simply do not want any country to be left out and thus to inadvertently gain an advantage in global competition.

17 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract (Wordsworth Editions, 1998).

18 Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto (Oxford University Press, 1998).

19 Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Winter Notes on Summer Experiences, trans. David Patterson (Northwestern University Press, 1997).

20 Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (Routledge, 2005), 124.

21 ‘Genußmenschen ohne Liebe und Fachmenschen ohne Geist, dies Nichts bildet sich ein, auf einer in der Geschichte unerreichten Höhe der Menschheit zu stehen!’ Quoted in Max Weber, Gesamtausgabe, Die protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus (J. C. B. Mohr, 2016), 488; Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, 488.

22 James Burnham, The Machiavellians [1943] (Lume Books, 2020).

23 ‘Purity is a concept of fakirs and friars. But you, the intellectuals, the bourgeois anarchists, you invoke purity as your rationalization for doing nothing. Do nothing, don’t move, wrap your arms tight around your body, put on your gloves. As for myself, my hands are dirty. I have plunged my arms up to the elbows in excrement and blood. And what else should one do? Do you suppose that it is possible to govern innocently?’ Jean-Paul Sartre, Les mains sales (Gallimard, 1948).

24 William Shakespeare, Henry VI, Part Three (Oxford University Press, 2002).

25 David Runciman, Political Hypocrisy: The Mask of Power, from Hobbes to Orwell and Beyond (Princeton University Press, 2018).

26 Gerhard Schulze, Die Erlebnisgesellschaft (The Experience Society), (Campus-Verlag, 1993).

27 Michel Foucault, Politics, Philosophy, Culture: Interviews and Other Writings 1977–1984. Lawrence D. Kritzman, (ed.), (Routledge, 1988).

28 Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion, trans. William R. Trask (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1987), 203–204.

29 Daniel Bell, The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (Basic Books, 1976).

30 Thomas Molnar, Bernanos: His Political Thought and Prophecy (Routledge, 1997).