In 1787, on the eve of the most eminent modern political revolution, an anonymous pamphlet was published in Germany with the title ‘Wer sind die Aufklärer?’(‘Who Are the Enlighteners?’). The author of the pamphlet also indicated that a new era of knowledge is beginning in the world, where the separation of ‘superstition’ and ‘reason’ will now be definitive. According to the anonymous draftsman, spirit and nature are two completely different realities, which is why there is a need for a ‘spiritual science of the spirit’ (Pneumatologie des Geistes) which must be distinguished and separated from the description of the phenomena of nature. With this, it was possible to declare the separation of natural science and spiritual science into two —which until then was supposedly the main obstacle to progress.

According to the pamphlet, a kind of tabula rasa is needed, something according to which the desired new society could be created. Just like Francis Bacon’s ‘new science’ in the Novum Organum, it cannot take anything from the old; the new political reality needs to be created based on a central plan, a scheme, constructed only by reason. According to this pragmatism, which was precisely in line with the abstract demands of the Sieyès ‘third order’, we should start not with the position of the human being in the world hierarchy (Great chain of Being), but with the ‘general person’, defined according to a constructed rational plan. As for the ‘common man’ defined in this way, he is supposed to be ‘rational’, according to his nature, he just needs to be allowed to ‘function rationally’—as liberalism presupposes and things in the world will sort themselves out.

The other possibility is that the ‘rational man’ must be subjected to some kind of ‘rational plan’, the appropriate human action must be formed, with the effective support and help of a central power: as socialism and communism later thought. The intellectual revolution of modernity, propagated by the Encyclopédistes in the 18th century, proclaimed above all the supremacy of human reason over ‘superstitions and traditions.’

Scientific progress was perceived as also meaning moral progress.

The Aufklärist also hoped for their perspectives opening up to the infinite, while it was precisely in their age that the narrowing of human life to its purely material dimension began.

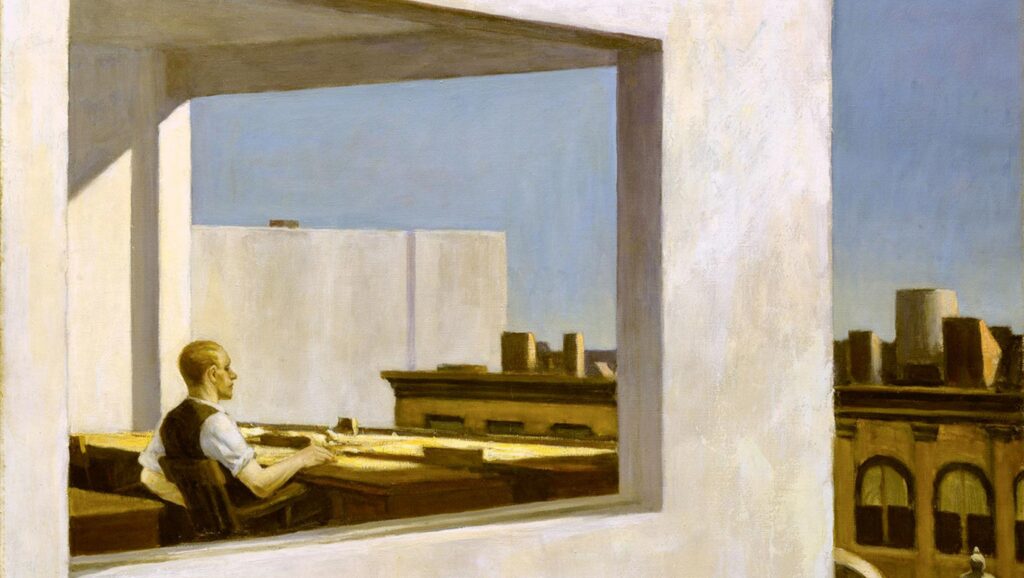

The same intellectual who first proclaimed the revolution of reason did not, or realized only later, that what he served was not leading to a higher order of freedom, but to a more complete determinism than ever before. The same intellectual who wanted to serve Humanity above all, and the same one who hoped to end political ‘tyranny’, will be at the mercy of a much more latent and at the same time much more sophisticated tyrannies during the 20th and the 21st centuries. As Kuehnelt-Leddihn puts it: in the highly technical modern world, we can encounter not only one type of tyranny, but a whole series of types of tyranny and slavery. The ‘tyranny of the clock’ affects everyone, the slavery of material prestige and ‘successful competition’ primarily affects the citizen, the salary-slavery above all the worker, and the school-slavery children. These different types of tyranny and slavery turn the modern metropolis into an ‘inhuman beehive’ completely subordinated to the demands of industrial work, and the modern employee (whether mental or physical) simply has no opportunity to set his own schedule, like a farmer or craftsman in pre-Industrial ages. Ge lives in constant fear of being fired, ‘the lack of independence is almost written on his face.’[1]

It would be difficult to describe the state of the world following the Revolution of Reason with the term freedom. Perhaps it was too late for the Aufklärist intellectual to realize that what he served was not freedom, but rather something, that could be characterized as the opposite of freedom: a machine.

The machine is pure—and sometimes deadly—rationality. The pure idea of efficiency that materializes in modernity, such as five-year plans, death camps, or carpet bombing. The machine itself was previously hidden by ideals such as: freedom, prosperity, abundance and, above all, the general concept of ‘progress.’ Just as the modern intellectual as an Aufklärist philosopher helped to eliminate the old aristocracy—partly by the aristocracy itself becoming modern intellectuals and partly by the intellectual making himself the aristocrat of the new world, he soon received other patrons: instead of the church, kings and landlords, technicians, bankers, manufacturers, and investors. The freedom of the spirit—as before ‘philosophy was the servant of theology—is now tied up by machines and the merciless rationality of the market and the almighty economy. All this not only eliminates the independence of individuals and states from the specific rationality of the market, but above all, it also eliminates the inner independence of man from the material sphere. The merciless rationality of the economy, in the current phase of modernity, imposes itself on everything and everyone, although typical modern politicians still talk about culture and the importance of ‘spiritual values’, it is becoming increasingly clear that, in fact, what is really important to them is only profit.

While the almost exclusive pursuit of material well-being gradually excluded the spiritual and religious dimensions from life, in capitalism as well as in socialism, work started to be glorified as a value for its own sake.

Real odes to the ‘asceticism’ of work began to be written.

Such an ode is Stakhanovism in socialism, or the ‘ethics’ of the ‘hard-working’ capitalist entrepreneur. But since in neither case can we find any characteristic that reminds us of the traditional concepts of knowledge, even vaguely, the modern intellectual also appeared as an inventor, a natural scientist, as a manufacturer ‘experienced’ in political and social issues, (and later: tech-manager), as ‘technical intellectual’. However, where the hope of economic abundance overwhelms outstanding intellectual performance, true intellect has few opportunities to manifest itself. In a world driven by efficiency and profit maximization, today the intelligentsia must provide more and more additives for the general and increasing mechanization of life.

This banalized understanding of knowledge ultimately gave birth to what the Catholic philosopher Tamás Molnár calls the ‘knowledge industry.’ It is the knowledge industry that places the intelligentsia in the service of a pragmatic order instead of the search for truth. It deprives the traditional arena of education, the university, of its dignity. Even if the young student has a thirst for knowledge for its own sake, the knowledge industry will soon replace it with the hope of successful integration into society. The future intellectual feels that if he hasn’t already done so, he must now adapt to the prevailing ideologies and do what is expected of him.[2]

The mind was defined by John Locke as a ‘blank slate’. According to Locke, it is up to us what exactly we write on the blank pages of our mind. Of course, all of this is possible only by taking a decidedly anti-Platonic position, denying all kinds of innatism, that is, completely opposing the greater part of the concepts of knowledge that preceded modernity. Convictions like this also give rise to the outstanding importance attributed to education in systems with a ‘progressivist’ approach.

However, it is rarely taken into account that forcing a general expansion of education also means levelling. And if something is extended in a general and obligatory way, then it will be quantitative rather than qualitative. If we imagine all of this in a school system that is universally compulsory for everyone, then according to today’s well-known hierarchization of knowledge, only knowledge that can be (easily) validated in the so-called ‘labour market’ will be truly appreciated. Only that kind knowledge will appear as desirable, which is inherently somehow mechanical, machine-like, technical.

Other kind of knowledges are, so to speak, labelled unnecessary in the modern world—one either learns literature and history or one does not—and there is hardly any mention of philosophy or theology as ‘meaningful’ knowledge. With a little exaggeration, we could even say that in the conditions of modern technical civilization, the existence or non-existence of humanities is almost completely irrelevant, and with this, we can clearly say that the classical endeavour of knowledge as truth completely disappeared. The abundance of material goods that can be obtained through the serving of the machine, as a need for the practical purpose of life, overwhelms any higher value and demand. The modern intellectual still desperately tries to maintain the appearance of his own importance, but in recent times, his knowledge is therefore almost only needed when it is aimed at some kind of practical application, regardless of how it is articulated rhetorically.

His metaphysical indifference to truth always results in his relativism. And relativism: if it simply declares that everyone is right ‘in a certain way’, then it is really little more than a simple wordsmithing. There is no ‘good’ and ‘bad’ or ‘true’ and ‘false’, only sentences with a practical meaning are acceptable. ‘I am right from my point of view, and you are right from your point of view.’

Accordingly, the modern intellectual no longer aspires to be a morally outstanding individual, perhaps the keeper of the ‘wisdom of the ancestors.’ As László F. Földényi writes, he views existence in a rather desperate way. ‘Personal life is subject only to the laws of origination and passing away, which in turn are not law-like, but blind, uninfluenced and unpredictable…man cannot withdraw himself from the universal disintegration; even when he tries to cover chaos with the mask of order, he is still a prisoner of complete anarchy.’[3]

But, no matter how we try to shape this bleak basic experience, decorate it with words, or cover up the undoubtedly serious, dark and even tragic nature of the matter, perhaps describe that the only decent attitude towards the facts of modern life is that ‘we can’t do anything about it’ a meaningful culture cannot be founded on this nihilistic experience.

If this worldview really lives up to the ‘top thinkers’ of our time: chaos instead of cosmos, determinism instead of freedom, all-encompassing relativism and scepticism, then where will it lead to the masses who, at a much lower level than the leading intellectuals, can only perceive the same things of modern existence as a pervasive, fundamental chaos-experience?

Resurrecting the Middle Ages —Middle Ages in the ideological and spiritual sense—against the most diverse modern tendencies of cultural decline could be a noble conservative idea, but it would be a utopian demand as well. The ‘medieval oikumené’ is lost. It is indeed the last unit in the history of the West in which one can still speak of true intellectuality, but today, even its resurrection in an analogical sense is quite impossible. However, in spite of the incredibly strong headwind, even in the most modern environment of the ‘knowledge industry’, there are people whose consciousness has not been completely put at the service of the machine-system.

They are those who see something of the essence, and who are not completely overwhelmed by the ever-accelerating flow of modern phenomena, who—if uncertain for the time being—can withstand the drift of the alleged ‘progress’. Even today, some people are able to rise above the soulless machinery of the economy’s supposed rationality, or simply decide to no longer serve the global ‘equalizing’ (levelling) mechanism of the industrial-technical interests of the modern knowledge industry. For those, who are contemporary but not modern, for those who want to grasp the object of knowledge in such a way that they are connected to it at the root of our being, a specific, new kind of attitude is necessary for knowledge.

[1] Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn (Francis Stuart Campbell), The Menace of the Herd, The Bruce Publishing, Milwaukee, Co. 1943, 137.

[2] Tamás Molnár, Én Symmachus/Lélek és gép, Budapest, Európa, 2000, 49.

[3] László F. Földényi, A túlsó parton. Esszék, 1984-1989, Pécs, Jelenkor Irodalmi és Művészeti Kiadó, 1990, 150.