‘There is none’, answers Hölderlin in one of his poems (‘In lieblicher Blaue’), famous also for the commentaries made about it by Martin Heidegger in a lecture from 1951. For Hölderlin, the measure can come only from on high, where in the lovely blueness above the metal roof of a Danubian-style church tower dwells God. For Heidegger, the meaning of this line is principally that there is no measure on earth anymore, because we are measuring it (and what is on it) too much with our technical, geo-metrical mind, while we are losing contact with the authentic, fundamental measuring that belongs to the ‘heavenly’ metrum of poetry and of poetical living: ‘dichterisch wohnet der Mensch…’ is in fact one of the famous lines of this poem and the title of the mentioned Heidegger’s lecture.

Heidegger is probably right on this point. If we look back at the just passed Christmas festivities, we can probably agree that our experience of this time of the year, that should incline us to the joy and peace of shared, heavenly uplifted thoughts and feelings, too often ends up in a consumeristic frenzy of gifts, special food, special activities etc. What should be just the background of something deeper becomes the predominant goal of our festive efforts, the latter becoming therefore something for its own sake, a will with no real end and measure, a ‘Will to Will’, as Heidegger paraphrases Nietzsche’s Will to Power.

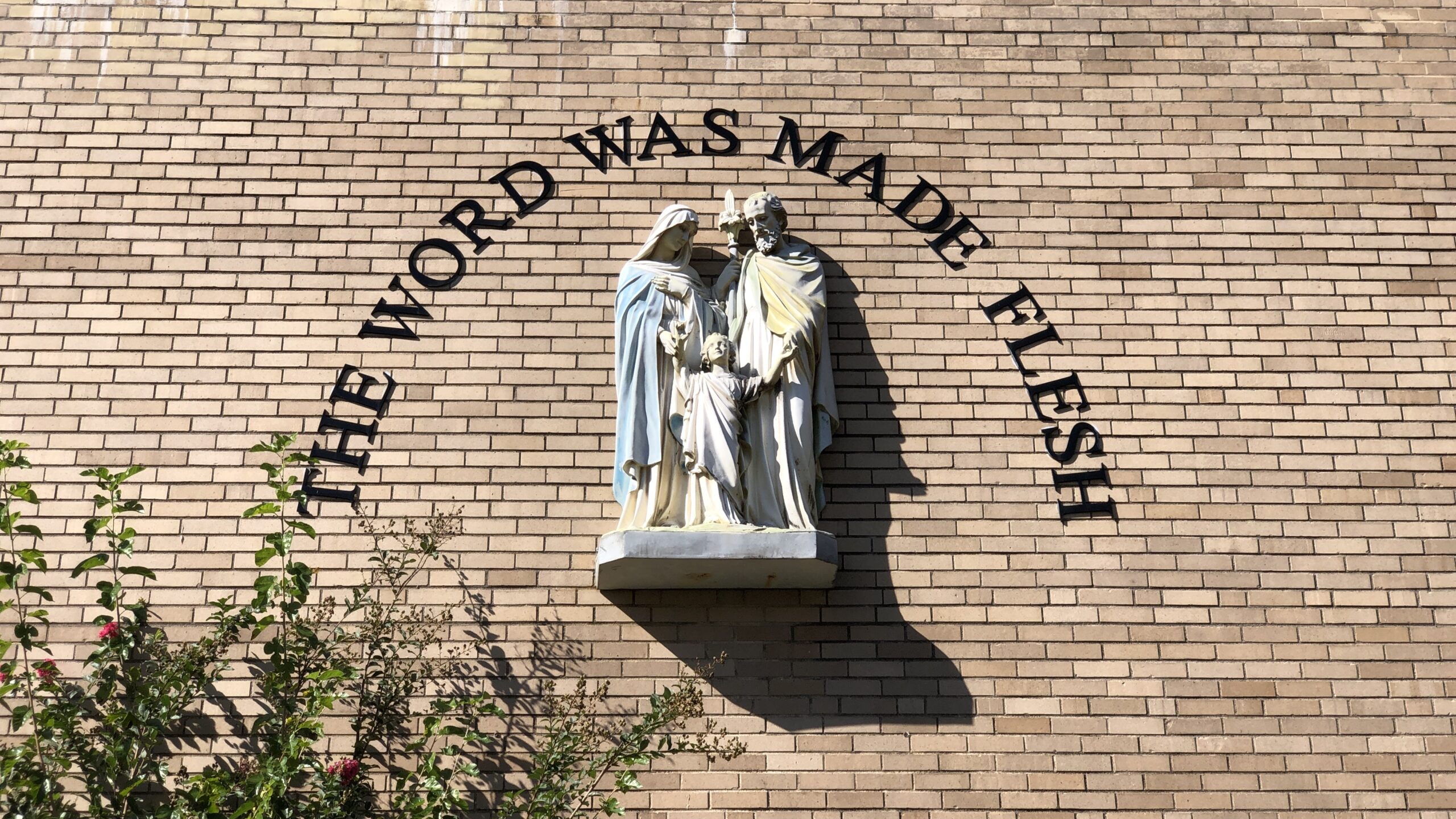

I think it would be a really good idea to think on these occasions (and on many others as well) about the possibility of a more poetical living, to which Heidegger’s interpretation of Hölderlin is calling us: shouldn’t we take, for example, the Christmas tree and the Nativity scene not just as objects to be made, even skillfully and according to local traditions, but also as something to be contemplated within the host of meanings and associations (frequently very personal) they evoke in the context of its main meaning—the Incarnation of the Son of God. Christmas is indeed a very ‘incarnated’ festivity also in the sense that it presents us its heavenly content (Hölderlin’s ‘Measure’, if you want) through an abundance of earthly traditions: lux in tenebris lucet. Isn’t therefore the meaning of Christmas that from Bethlehem onward there is a Measure on earth? But are we still able to experience it?

‘Christmas is indeed a very “incarnated” festivity also in the sense that it presents us its heavenly content through an abundance of earthly traditions’

It is quite obvious that present Western humanity is seriously obstructed on its way to such an experience: I think that one of the main reasons for this fact is the rejection of Aristotle’s Metaphysics (another topic dear to Heidegger) that happened in Modern Philosophy from Descartes on. Classical, Aristotelian metaphysics indeed provides us with the only natural measure for our living on earth: this measure is displayed in Aristotle’s distinction between being in act and being in potency. This distinction, which presents the only possible way to overcome the paradoxes of Early Greek Philosophy, namely those of Heraclitus and Parmenides, presents also the only possible way to designate the distinction between good and evil in a way that has not mere subjective but real, objective stringency. Good is, in this sense, the objective actualization of our objectively given potencies, while evil is whatever is contrary to such an actualization. For example: I am endowed with a rational capacity: therefore, it is good if I develop it through the study of different sciences, but it is bad if I hinder it with drinking too much alcohol. I am also endowed with a reproductive capacity: therefore, it is good if I use this capacity to its full actualization, i.e. to have children, but it is bad if I use this capacity in a way that hinders such a full actualization, as it happens with the use of contraceptives or in homosexual relationships. Evil it is also to kill an innocent human beings since in this way it is precluded the way to any actualization of its potencies, as it happens in the case of abortion and euthanasia.

Can there be another natural measure of our existence on earth than the distinction between act and potency? It comes, therefore, as no surprise that since Western humanity rejected this distinction in the context of Modern Philosophy we have lost any kind of measure for our existence and abandoned ourselves to mere arbitrariness, within which also the sense for the supernatural and sacred is lost.

Cleary, I disagree here with Heidegger. For him metaphysics is a unitary reality that goes from Plato to Nietzsche, including Aristotle, as well as the authors of Modern Philosophy, and it is something that we should overcome in a different, more poetical way of thinking, one that acknowledges the ontological difference between being in the verbal sense (Sein) and being in the substantive sense (Seiende). Since, for Heidegger, the first sense of being is the foundation of the latter and is, therefore, the foundation of everything, the foundation (Sein) should not be defined, should not be substantivized, and this is exactly what metaphysics does with its precise language, but should be left instead to a more allusive, poetical, open kind of language. This is why for Heidegger the Measure has to be a poetical, and not a metaphysical, reality.

Isn’t maybe Heidegger right also on this point? Isn’t the language of (Aristotelian) metaphysics a deeply technical, unpoetical language that narrows our experience and reduces it, at a basic level, to a shallow technical frenzy much similar to the one we are experiencing today and in the Christmas season as well?

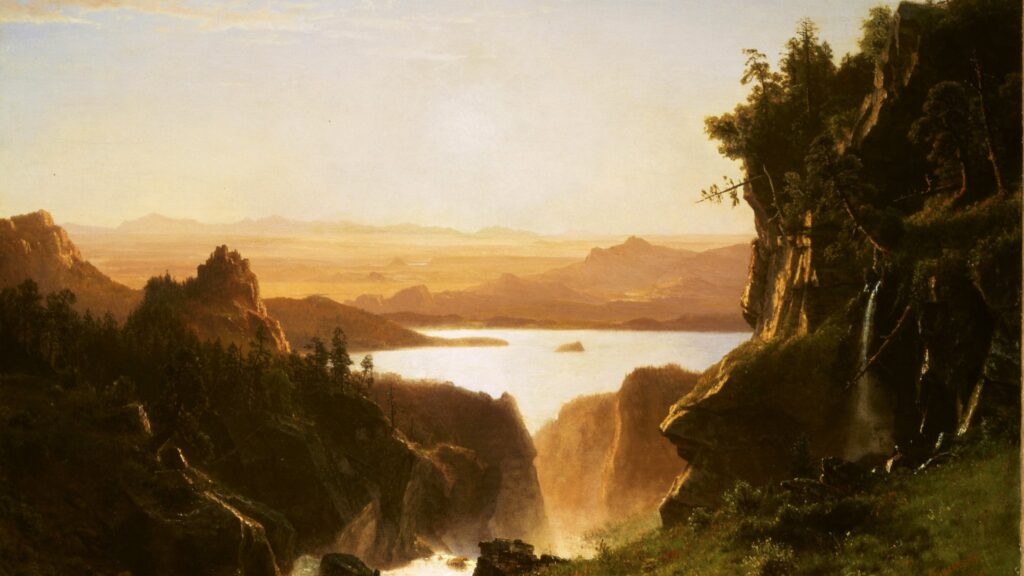

Exactly the contrary is true. It is the metaphysical distinction between act and potency that brings depth to being, since it reveals to us that being is not just a fact that is or is not in a shallow binary fashion, but is something that hides in itself a treasure, potency namely, that can be increasingly brought to light through a process of actualization, which is, in the end, open also to a supernatural, infinite actualization in God as Being Itself (Ipsum esse subsistens), as St Thomas Aquinas suggested, enhancing Aristotle’s view. Isn’t this the true source of the poetical experience of the world: seeing in the things around us something that transcends them but without negating them? Isn’t Heidegger’s concept of poetry a much less poetical one, since for him the difference between being (Sein) and worldly beings (Seiende) is so radical that the latter or the former has somehow to be negated, has to disappear in a Parmenidean or in a Heraclitean way in front of the Fundamental thought? But what is then left for poetry if there is nothing to speak about or if it is not possible to say anything about the heavenly Foundation of all things that bestows on them their poetic dimension? Poetry is not the synonym of silence.

Therefore, we can conclude that there is a measure on earth, if we want to use it, and that it is a poetical measure indeed, as Heidegger demands. This measure is the philosophy of Aristotle, rooted in his fundamental distinction between act and potency. The conservative movement must make use of it in the argumentation of its core values, if it really wants to bring back a measure to the world.

Read more from the author: