Over the last couple of months, the brutal crackdown on the protests in Iran has reminded us how the draconian the regime of Ayatollah Hosseini Khamenei is, paralleling those of Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin. The justification of the suppression of their citizens’ God-given natural rights, even to the point of murdering innocent people, by these dictators is based on the pretext that it is the only way to maintain harmony within their respective countries. While these despots have not spelled it out in such terms, their argument is founded on the philosophy of the laws of nature of Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679).

Hobbes devised a doctrine of natural law, essentially a collection of socio-political philosophical principles, based on his personal experience of and reflections on the actual course of chaotic human affairs in England. He saw first the struggle that led up to the deposition and execution of King Charles I, then the civil war campaigns under Oliver Cromwell, the anarchy after Cromwell’s death, the restoration the monarchy under Charles II, and the continual strife between the king and the Parliament, as well as among various religious groups.

Seeing the Church of England as unreasonable and ineffective in the aforementioned crisis, his concept of the law of nature subordinated the independent ecclesiastical law to the natural law of the omnipotent and sole person of the state represented by the monarch. His views can be compared to those of Martin Luther, who called for freedom of conscience in opposition to the medieval ecclesiastical authority, arguing that it would be man’s inmost freedom (his personal faith in Christ) and not the institutional Church that would save him. This concept of ‘emancipation’ would later be exploited by the Enlightenment thinkers, specifically by Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), as was manifested in his sapere aude (meaning dare to use your reason for yourself).

Hobbes’ Social Contract

The point of departure for Hobbes’ political philosophy on the natural law and natural rights was man’s state of nature, which he argued is nothing other than a continuous state of war. Given this situation, man being what he is, would naturally behave in an unethical manner ‘if there were no authority to enforce law or contract’[1] that would bind him to observe moral principles. Taking into consideration man’s appetitive and deliberative nature, without any law or contract enforcement from a secular higher authority, his conduct would by its own nature be a constant struggle with every man–an incessant clash for power over others. Hobbes’ point was to demonstrate that ‘this condition would necessarily thwart every man’s desire for “commodious living” and for avoidance of violent death, that therefore every reasonable man should do whatever must be done to guard against this condition, and that nothing short of every man acknowledging an absolute sovereign power is sufficient to guard against it.’[2]

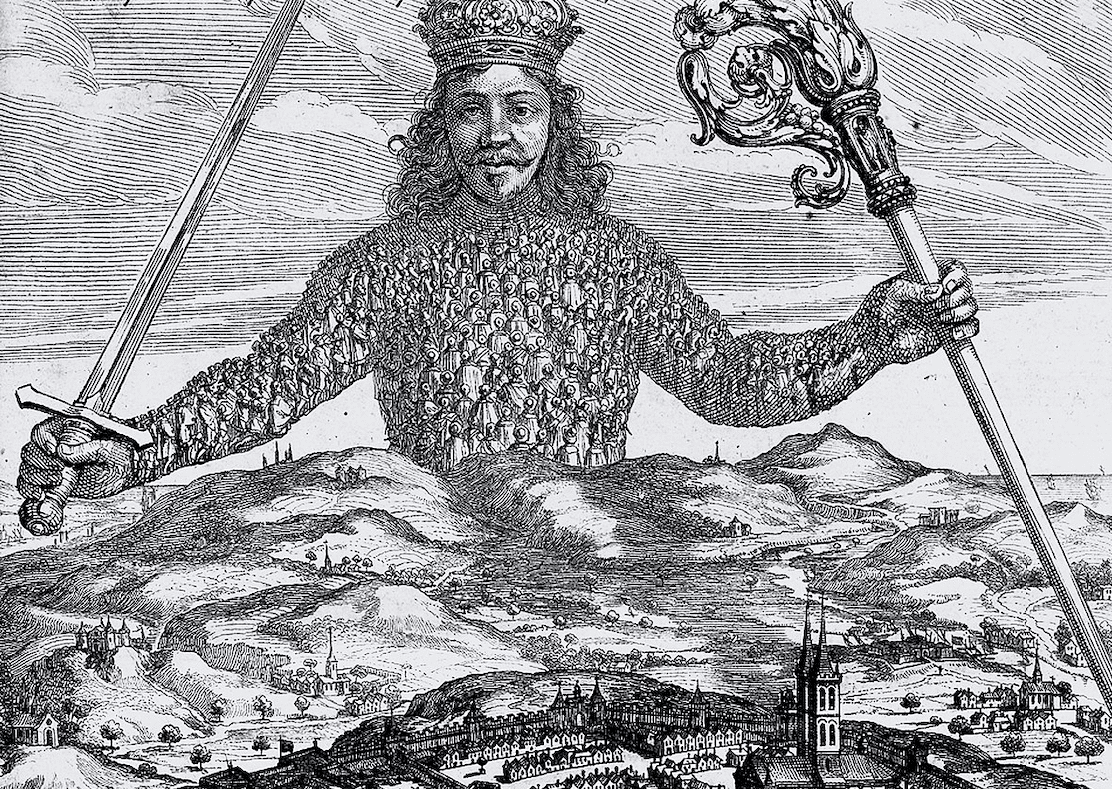

In his Leviathan (1651), Hobbes portrayed man as substantially ‘self-interested, always seeking “more intense delight” and a strong position, as Machiavelli had held, from which to secure their ends.’[3] Clashes of interest and the contention for power define the human condition.

Man’s knowledge is solely geometric, based on empiricism and rationalism.

Thus, ‘while God has decreed the laws of nature, man has no innate understanding of them, as is shown by varying human opinions over what natural law requires.’[4]

Hobbes inadvertently finds himself in a social world, in which the starting point is not a political concept, but the sole individual. The natural law, therefore, is reduced to the individual adhering to dealings with others only if there is enough ground for believing that others will do likewise.

In the state of nature, while man seeks more power to protect himself, some seek more over others. And the only way for social harmony is to show man that he lives in a society which necessitates norms from a sovereign.[5] His dilemma is not the laws of nature in relation to the will of God, but rather ‘under what conditions will individuals trust each other enough to “lay down their right to all things” so that their long-term interest in security and peace can be upheld?’[6] The solution was that man needs to be guided exclusively by the decisions of the state:

‘Since therefore such opinions are daily seen to arise, if any man now shall dispel those clouds, and by most firm reasons demonstrate that there are no authentic doctrines concerning right and wrong, good and evil, besides the constituted Lawes [sic] in each Realme [sic] and government; and that the question of whether any future action will prove just or unjust, good or ill, is to be demanded of none, but those to whom the supreme hath committed the interpretation of his Laws.’[7]

It is important to highlight that while Hobbes’ concept of the sovereign was one in which the state was a self-perpetuating absolute power, its authority is conceded to it by the people—through a social contract. It is, to use a modern term, a liberal position in that Hobbes seeks to resolve the dilemma of establishing ‘both liberty of the individual and sufficient power for the state to guarantee social and political order.’[8] In like manner, it is what Putin did when he illegally annexed the four Ukraine regions of Luhansk, Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson with the bogus referendum of 30 September:

‘A multitude of men, are made One Person, when they are by one man, or one Person Represented; so that it be done with the consent of every one of the Multitude in particular,’[9] Hobbes declared.

Hobbes contrives natural law as a means of self-preservation.

He refuted traditional higher law tenets and motivated people to accept the established laws and customs of their nations, even if they appear oppressive, for it is the only way peace and security can be obtained in society. The state thus becomes successful at the expense of justice, as it is today in the Islamic Republic of Iran, the People’s Republic of China, and the Russian Federation where power divorced from justice maintains order through oppression.

It was never Hobbes’ intention to justify the repression of human dignity. However, it is vital to understand that the (full) voluntary surrender of individual rights goes against the principles formulated by Thomas Jefferson in the Unites States’ Declaration of Independence:

‘…that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government.’

[1] C. B. MacPherson, The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2011, 19.

[2] MacPherson, The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism, 19-20; cf. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, London, Penguin Books, 1981, 223-228.

[3] David Held, Models of Democracy, Stamford, Stamford University Press, 2006, 60.

[4] Christopher A. Ferrara, Liberty: The God that Failed, Tacoma, Angelico Press, 2012, 57.

[5] Cf. MacPherson, The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism, 69-70.

[6] Held, Models of Democracy, 61.

[7] Thomas Hobbes, De Cive, New York, Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1949, 10.

[8] Held, Models of Democracy, 61.

[9] Hobbes, Leviathan, 220.