Hungarian Conservative has already covered prominent scientists whose worldview was profoundly influenced by Christian teachings. Among them are such personalities as Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, whose philosophical framework united science and Catholic teachings. Or, for another example Ányos Jedlik, Hungarian 19th-century inventor and a Catholic priest who is known as the first academic to ever lecture in Hungarian. Given that the aforementioned individuals represent Western and Central Europe respectively, it is time to cover the life and teachings of intellectuals emerging from the Eastern part of the continent.

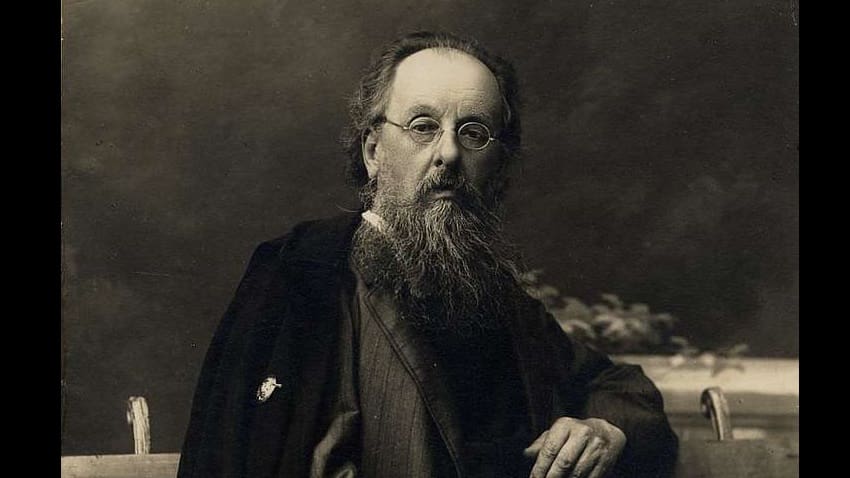

Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky (1857–1935) was a Russian and early Soviet rocket scientist of Polish, Russian, and Volga Tatar ancestry who pioneered human spaceflight.

It was Tsiolkovsky who first discovered the escape velocity from Earth into orbit (8 km/second, or 5 miles/second)

and envisioned that this could be achieved by using a multi-stage rocket technology fueled by liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen.

He published an immense corpus of scientific works dedicated to the field of rocket technology and left an incredible legacy that allowed for the first ever human steps into space, including the famous flight of Yuri Gagarin in 1962, the first man to fly above the atmosphere. Today, along with Robert Esnault-Pelterie, Hermann Oberth, Fritz von Opel, and Robert H. Goddard, he is considered to be the father of modern rocketry and astronautics, although he operated separately from these fields. For a self-taught scientist with debilitating hearing problems from the outskirts of a Russian provincial town, that was truly a heroic deed of unmatchable courage, intellect, and determination.

What is less known is that he essentially wrote his groundbreaking contributions to rocket theory as supplementary notes to his philosophy of space exploration, which was the primary focus of his attention and consumed most of his efforts. What is even less acknowledged is that the philosophical foundations of his framework had an inalienable influence of Christianity that played an important role in shaping his perspective, a fact which Tsiolkovsky himself recognized.

The ideas of Tsiolkovsky are set in the tradition of Russian Cosmism, a school of philosophy that essentially combined the overarching influence of natural sciences with Christianity, arguing for the compatibility of the two.

The forefather of Russian Cosmism, religious thinker Nikolai Fyodorov, believed that the message of Christianity to humanity is that Mankind should not indulge in escapism and ignore the miserable order that has been established after the Biblical Fall. Rather, the mission of Man is to change this order for the better, the order that now produces physical and moral hardships, struggle for resources, the existence of one form of life at the expense of another, and the alienation between people and death, which represents the highest and most horrendous evil of all. According to Fyodorov, by breaching the gates of Hell and freeing the tormented souls, Christ himself showed us evidence that the unjust world can be altered, even if we consider this injustice to be the natural order of things. In this grand quest, science shall serve humanity as the tool for improving the world for the better, as it is impossible to change anything without understanding how it operates.

He also thought that after finally defeating the inevitability of death, the next logical implication would be to liberate those who have already been ensnared by its cold grip—a notion reminiscent of and inspired by the Christian concept of the second coming. As when the resurrection of all who have passed away happens, there will not be enough place to accommodate all the reborn billions of people, humanity has the moral obligation to colonize the vast expanses of the Cosmos to provide living space for its resurrected ancestors. Thus, Fyodorov tried to combine Christian worldview and ethics with science, where the narratives of the former serve as the guiding light for the latter.

Tsiolkovsky influenced the development of this philosophical tradition by making notable contributions to it.

Independently from Fyodorov, he reaches the understanding that it is of paramount importance for humanity to colonize space,

which he viewed as a way for humanity to reach Salvation. Albeit he deviated heavily in some aspects from the traditional Christian teachings (he interpreted the immortality of souls through the indestructibility of atoms, which does not, to put it mildly, fit the Christian understanding of the subject), he nonetheless attempted to make his scientific worldview compatible with the Biblical teachings, probably owing to the fact that his father and mother were devout Polish Catholic and Russian Orthodox believers, respectively.

Whereas in his main works, such as Space Philosophy and The Will of The Universe, he primarily explains the philosophical system of his own, reflecting on Christianity only occasionally, in his more Christian-centred works, such as Palestine—the Birthplace of the Galilean teacher, The Gospel of John in Everyday Language with Explanations, and Christianity (Gospel of Matthew with Commentary), he pays more attention to the faith. He believed that, in order to understand better the creation of God, i.e. the Universe, it is imperative to study it wholistically, as humanity is an inalienable part of it. Hence, the imperative for space colonization resurfaces as a moral necessity, given the inherent impossibility of comprehensively studying the universe as a whole within the constraints of a singular planetary entity.

God in this picture is ‘supreme love, boundless mercy, intelligence and the cause of everything’. Interestingly, he understood the figure of Jesus not merely as the quintessential exemplar of morality, with his teachings serving as the ideal moral compass for all humans, but also as someone who understood the most fundamental laws of the Universe, thus possessing the ability to govern them effortlessly. In that sense, Jesus Christ was the most powerful naturalist and scientist that ever existed, as his understanding of the Universe allowed him to manipulate its laws, thereby demonstrating to humanity the imperative need to study and understand it.

This was especially important for the worldview of Tsiolkovsky, as he saw the rise of morally impeccable individuals with supreme intelligence as a necessary prerequisite for the subsequent exploration and settlement of outer space by the human race.

Besides, he also reflected on the nature of the Holy Trinity, agreeing with its message: ‘It is true that the spirit of truth comes from the Son, i.e. comes from Man, and Man or any other rational being comes from the Father, all together are one’.

Moreover, he emphasizes that his ethical system is inherently Christian, pointing out, however, certain discrepancies in the origins of the two: ‘[The teachings of Jesus] come from faith and life. They are more intuitive. Mine are from the depths of hard science’. Essentially, however, in that passage, he noted that the nature of the scientific inquiry is not just compatible with Christian ethics, it reaches the same moral conclusions.

The teachings of Russian cosmism and the ideas put forth by Tsiolkovsky can serve as a source of inspiration for us.

While it must be noted that Tsiolkovsky’s ideas undoubtedly align with aspects of Christian teachings not emphasized in traditional Christian churches occasionally, they nonetheless provide us with a compelling example. They demonstrate the possibility of basing our perspective on traditional societal foundations while embracing scientific progress, amalgamating the ideational influence of both realms to produce something of even greater value.

Related articles: