Read the first part here.

Crisis Philosophy

Modernity, according to Prohászka, is first and foremost a crisis. It is not a crisis or crises of modernity that we can speak of, but rather, modernity is itself a crisis.[1]

‘…It is a peculiar and surprising fact that modern culture, built on science, despite the fact that it ultimately led to a crisis, and that there were always diagnostics of this crisis, nevertheless kept alive a constant and continuous sense of progress in modern man: the 18th century, and especially the 19th and early 20th centuries, until the outbreak of the world war, so to speak, were full of this slogan of progress, a slogan of triumphant progress. It is a characteristic symptom of this that even today there is a real indignation on the part of the older generation when someone is so bold as to describe this period as an age of decline.’[2]

Or elsewhere:

‘We do not see human development as linear, but rather as cyclical, and we feel that we are at the end of a long, centuries-long cycle; not the imminent golden age before us, but the decline and the imminent death…The mood of decline is triggered in most of us by the sight of the frightening massification of all modern life and culture. And this massification and other characteristic features characterize our time. It is not without reason that Spengler and cultural critics like him refer to his historical analogy, the late Roman imperial period, the secular mass movements of the late Middle Ages: the final weakening of every culture begins with mass rule.’[3]

‘What strikes the observer of the present age above all else is the peculiar feature that we have lost our faith in progress…We could not imagine then[4] that development could not be progress, that is, ultimately a straightforward progress, interrupted at most by stagnation. And for many, this progress was still the only thing they believed in…We are no longer proud of progress, and we are almost afraid of it, lest it should take away what remains of the fragments of the old world. And with our faith in progress, our view of history has been shaken.’[5]

Prohászka’s view of modernity cannot be understood without a broader analysis and interpretation of the crisis philosophy that was taking root in the 1930s and 1940s, and without a certain perspective on it. As Szilárd Farkas puts it in his work on the 20th century interpretations of crisis in Hungarian philosophy:

‘The first decades of the 20th century are in many ways of particular importance for the present study, since Europe was faced with a series of cataclysms as never before. At the same time, it was a particularly productive period in the scholarly and intellectual life of the continent, and of Hungary in particular. The problem of crisis is also receiving considerable attention.’[6]

‘What strikes the observer of the present age above all else is the peculiar feature that we have lost our faith in progress’

According to Farkas, the theme of crisis (especially under the influence of Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and Spengler) was thematized by the following outstanding figures of Hungarian intellectual life in the period between the two world wars: Béla Brandenstein, Béla Hamvas, Sándor Tavaszy, László Széles, Sándor Koncz, István Bibó, Lajos Fülep, and Lajos Prohászka.[7]

In addition to the names of Nietzsche, Spengler and Kierkegaard, it is worth mentioning the names of René Guénon, Frithjof Schuon and Julius Evola, and Leopold Ziegler, who is more distantly related to them, especially Guénon. Among the most powerful manifestations of the crisis philosophy are, for example, Guénon’s The Crisis of the Modern World (1927), Evola’s Revolt against the Modern World (1934) and Ziegler’s The Change of Colour of the Gods (Gestaltwandel der Götter) and Tradition (Überlieferung) (1936).[8]

The prominent emergence of crisis philosophy in the first half of the 20th century was not primarily the result of the political catastrophe of the First World War, the profound rearrangement of the continent’s political relations, the ‘transformation’ of monarchies into republics through revolutionary violence, or the great economic crisis of 1929–1933. The war, the economic and socio-political phenomena were merely expressions of the deep forces that accompanied the ideological and political unfolding of modernity itself.

In contast to crisis philosophy, many have said that every age is an age of crisis. It is true, as Hamvas argues in his influential essay ‘A világválság’ (‘The World Crisis’), that the Greeks of the time of Hesiod, the early Christian philosophers, or the thinkers of the Chinese Lao Tzu also spoke of the ‘crisis of their times’. However, crisis can be permanent, in the sense that it deepens and passes through history—just as, according to its proponents, progress can be slow and permanent.[9] However—and this tips the scales towards the possibility, credibility and relevance of crisis philosophy—, it is impossible to judge other ages as directly as our own, since our experience of other ages can only be indirect.

‘In contast to crisis philosophy, many have said that every age is an age of crisis’

As Prohászka puts it:

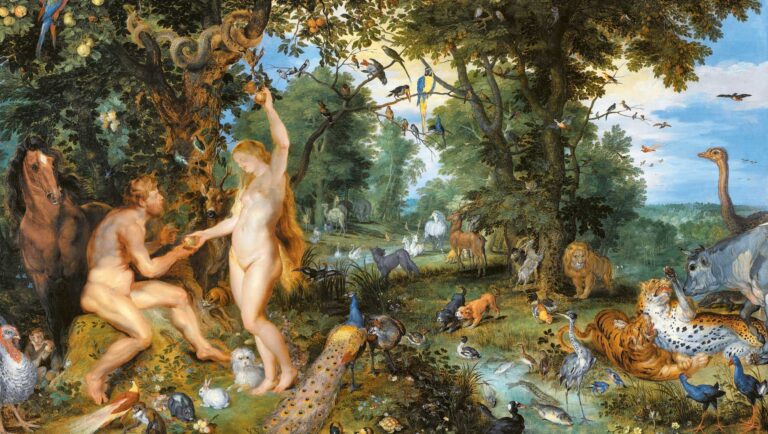

‘…In the great intellectual turn of the Renaissance, modern man is born. This process does not, of course, take place overnight. The threads of the modern man are slowly being prepared, and as we have already said, nominalism paved the way for him…The Renaissance man knows that he is different from the generations that preceded him, and he wants to be different.’[10]

We must therefore look for more fundamental connections, for roots that go further back in the history of ideas, if we are to answer the question of why crisis philosophy could become a dominant trend in philosophy (and especially in philosophical essay literature) between the two world wars. As in the case of Romanticism, or as in contemporary Germany, the phenomenon of the so-called ‘conservative revolution’ is in fact an elementary intellectual reaction against the ‘de-magicisation’, ‘Entzauberung’ of the world (see Max Weber).

The majority of Hungarian crisis philosophers (especially Hamvas and Prohászka) agreed that the crisis of modernity is above all a crisis of religion: the deep structure of the crisis is not the first total war, the subsequent political upheavals, the loss of identity of the masses of people forced into the cities, or the capitalist pursuit of profit, the general mechanization. These phenomena, according to Prohászka, can be traced back to a radical turning point in the history of European intellectual history, a turning point, which, on the one hand, far predates modernity proper and, on the other, belongs only partly to its history. This crisis is in fact: the secularization of man. One of the most important characteristics of modernity is the reduction of existence to a mathematical calculus, and this is above all to be found in the ‘de-meaning of the world’: rationalism as a philosophy is not a cause but a consequence, a projection of a spiritual turn in historical time.

Prohászka’s critique of modernity referred to three factors above all: the religious crisis (secularization); the proliferation of technology; and the moral crisis of modern man. His reflection on the crisis should be seen, above all, not in the light of other crisis thinkers, but rather in the light of the reflection on modernity given by the great majority of thinkers in the light of the ‘achievements of the age’. Progressivist worldviews, positivists, materialists and even thinkers with a religious or agnostic background, some of whom evaluated modernity positively, also viewed the decisive turn in human thinking, the secularization of man, as a positive development. (Conservative or modernity-sceptical thinking also reacted to the increase of man’s activity in the material sphere in the modern age: this is the origin of well-known concepts such as Spengler’s ‘Faustian man’.[11])

‘Prohászka’s critique of modernity referred to three factors above all: the religious crisis (secularization); the proliferation of technology; and the moral crisis of modern man’

Typical political forms of modernity, such as liberalism and congruent (modern) democracy (along with their close relations to capitalism) have been subject to many challenges and criticisms by political philosophers, thus, despite the big amount of ideologic faith concerning these forms of regimes, they can rarely provide a convincing reference point for a philosophically serious and convincing conception of progress. Totalitarian dictatorship, also closely associated with modernity and forms of democracy, was rejected by the genuine conservative and even some of the progressivist canon.[12] It was in Prohászka’s lifetime that the most negative consequences of modern totalitarianism became clear.

Thus, the theory of progress in the 1930s and 1940s (as today) could refer primarily to the material results of modern science as ‘objective results’ proving the fact of progress. It is argued that, as a result of the advance of the scientific worldview, by the last third of the 19th century humanity had overcome a number of difficulties which, in earlier phases of world history, had seemed insoluble. These include, first and foremost, food supply, health care, the reduction of high infant mortality and the reduction or disappearance of epidemics and diseases resulting from man’s coexistence with nature (such as, for instance, tuberculosis). This includes the general (material) enrichment that accompanies the increase in the financial economy, problems of public safety resulting from the general weakness of pre-modern state-power (lack of material resources and lack monopoly on violence), the resulting eradication of street violence, robber gangs or individual criminals (such as the so-called ‘betyár’ (outlaw) in Hungary). Among the arguments, ‘embourgeoisement’, ie the gradual disappearance of forms of life intertwined with animal husbandry and agriculture, and the employment of formerly agrarian populations in the industrial, commercial or service sectors, was also—albeit with more controversial emphases—included in the broader scope of ‘progress’.[13] (Some progressive thinkers, such as the very popular Harari in the present day, have also identified the ‘cessation of war’ as one of the main achievements of the breakthrough of the scientific worldview: this statement, however, in the light of geopolitics, can be described as utopian or unrealistic not only for the 20th century but also for the 21st century.[14])

Radical progressivism sought to extend the notion of progression to the realm of the human spirit.[15] If religion itself, in line with materialist and positivist assessments, is indeed only a ‘primitive explanation of the world’, then its loss or decline would not be a real disadvantage for ‘progressive’ humanity. If human beings are exactly what the stimuli of the objective environment make them, human beings (biological, cultural and social) are determined only by ‘evolution’: then culture and civilization are nothing more than a specific response to environmental conditions. Even if the human spirit does not exist as a substance or an entity in its own right, it too is a mere function of its environment, a reaction to it, does not exist even in the relatively stable condition of the human being (‘Conditio Humana’). If there is no distinction between absolute being (God) and relative being (the world), then there is no order in existence. If the idea of Order (world order) is merely the result of a rationalizing necessity existing on a more primitive level: the existing laws of reality are, in turn, merely properties, ‘laws without a Lawgiver’. Since there is no order, there is no displacement ‘with respect to what’. Or, again, in another way: in such a case, crisis can be appreciated, on the one hand, as a permanent feature of human existence, but since there is no crisis of religion, the crisis is always material: economic, political or war crisis; thus, crisis can always be overcome by finding a ‘method’.

Thinkers such as Nietzsche, who interpreted progress (and decline) primarily on a spiritual level, also perceived the crisis as a religious crisis, despite being explicitly atheistic and anti-Christian. Nietzsche, however, defined the ‘death of God’ as the possible beginning of something positive that could culminate in the possible deification of man. In Nietzsche’s powerful statement at the beginning of 20th century crisis philosophy: ‘God is dead’, however, the phrase ‘we killed him!’ is more significant than the mere statement of the fact of death.[16] (The Nietzschean interpretation of crisis and attempted solution, however, remained both a utopian and an isolated phenomenon in the history of European intellectual history.)

‘By eliminating the idea of God, they deny the very thing that distinguishes man from the animal’

However—and this has been noted, among others, by crisis philosophers like Prohászka—, in these self-confident deductions, there are actually too many ‘ifs’. On the one hand, the progressivist argument illegitimately conflates different spheres of existence, defines reality arbitrarily; on the other hand, it takes too much for granted. The results of the application of modern science, such as technological progress, do not prove or illuminate anything about whether modern science can answer the metaphysical context of existence, and the denial of a problem does not solve the problem itself.[17] Positivism and materialism, under the spell of extrernal results, are turning entirely outwards, towards the periphery of existence. And by eliminating the idea of God, they deny the very thing that distinguishes man from the animal: the reflection on one’s own being, the problems of human consciousness, the awareness or intuition of man’s mortality (and, by implication, its immortality). Here, in essence, such important fundamental philosophical questions are washed away or relegated to irrelevance as the principle and problematic nature of the ‘sufficient basis’ of existence: to deny the question of Being, or to define the basis of existence simply as ‘matter’ (itself a very problematic concept), is in fact as pseudo-solution.[18] Prohászka’s assessment of the crisis is also connected with his intense interest in the fundamental questions. He acknowledges or does not question many of the facts of material progress—and therefore he turns to the problem of progress, above all, as the problem of the general atheism of modernity. It is primarily in this context, and as a counterpoint to it, that he formulates his youthful essay ‘The Soul and the Absolute’:

‘The dialectical articulation of the soul in the world process is necessarily directed towards the Absolute, and form is the bridge that mediates between the soul and the Absolute…Throughout its history, metaphysical thought has been accompanied by the quest to find mediators between the Many and the One, the World and God, the Subject and the Absolute.’[19]

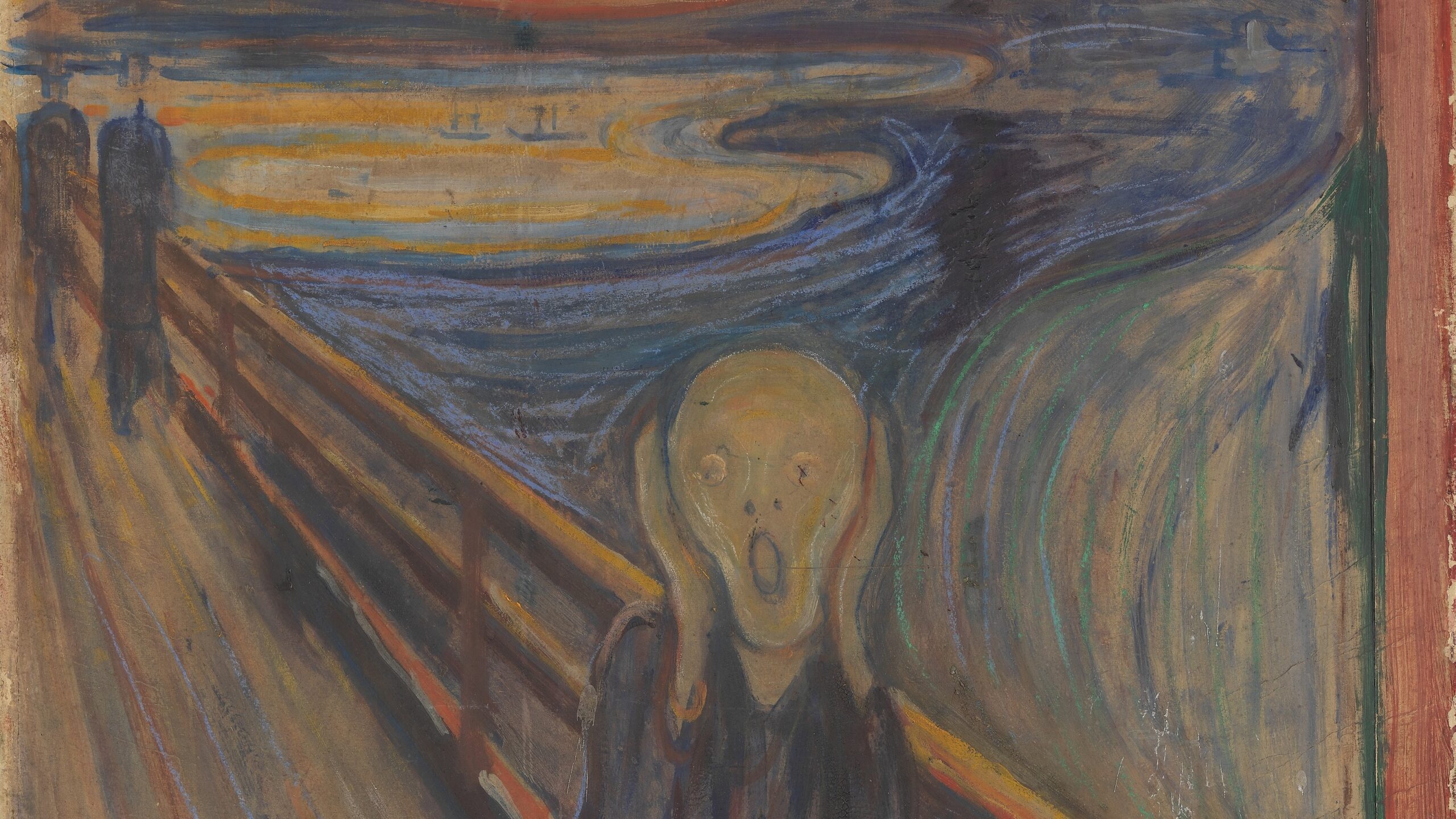

Prohászka have perceived that the blaring confidence of progressivist thought reflected only its inner emptiness, its blindness, its superficiality, its logical and philosophical inconsistency. What follows from these ‘new principles’ is, above all, a tragedy of human existence, more serious than ever before. It is the denial of the immortality (or the possibility of immortality) of the soul. In the light of this, all the material achievements of modern science, the improvements in hygiene, the conditions of healthcare, or the achievements of modern liberalism in terms of the assertion of ‘human rights’ can be considered as null and void. As Prohászka puts it so eloquently in his study ‘The Tragic Life Experience of Ákos Pauler’:

‘That horror of the lethal end which rushes towards us in Hamlet’s last words; “the rest is mute silence”, can only be experienced by the modern soul in its insoluble, unrelenting bleakness…Sickness, tearfulness, restlessness, the sight of the whirlpools that open on every side: this is the fate of modern man. No one has expressed this constant uncertainty, this metaphysical loneliness, with more despair than Pascal…“the eternal silence of these infinite spaces fills me with terror…” This terror, this fear of death, is the basic conception of modern man, the only haunting that confronts him everywhere, crueller than the ancient Moira, more terrifying than the eternal damnation of the Christian Middle Ages, for it is—Nothingness.’[20]

Although Prohaszka’s interpretation of the crisis, in comparison with contemporary thinkers influenced by Guénon and Evola—compared, for example, with the work of Béla Hamvas, was less strident, less rhetorically dramatized and in many cases more focused on the narrative aspect, alongside and behind a sober, even ‘academic’ vocabulary; still, it is no less upsetting and radical. In many respects, it also meets Hamvas’s interpretation: the basis, however, is different in more than one respect: Hamvas’s base is not explicitly Christianity, but rather universal (primordial) Tradition in the Guénonian sense. The way out is also seen in somewhat different approaches. Prohászka, even if in many respects he is like Hamvas, as he offers a very critical analysis and diagnosis of modernity, exhibits a more hopeful tone. He also does not believe in Spenglerian cyclical determinism, and for him the concepts of ‘Christianity’ and ‘Humanism’ are linked to the possibility of ‘pedagogy’: a belief that the erring human being can be corrected and educated—extending this experience to the whole of culture.

Faith in a possibility of healing was also described in the early Christian era in terms of metanoia—conversion/reversion. However, for Prohászka, too, this is only conceivable if the root of the crisis is revealed and the precise direction in which to turn is indicated: for metanoia is not simply a turning backwards, but rather a radical turn in the direction ‘perpendicular to history’ (Béla Hamvas). It does not simply mean philosophical, theological and political conservatism—although Prohászka’s thinking can rightly be called conservative, it does not imply ‘traditionalism’. Prohászka, despite his profound and radical critique, can hardly be called a complete and rigorous rejector of modernity, as Guénon, for example—but above all his philosophy is a kind of ‘rising above the drift’.

[1] In Arcanum ‘s interpretation, ‘crisis: is a turning point of an illness. International word from the Greek krisis (“to make a distinction, decision, turning point in illness”); its source is the verb krinó (“to divide, decide”).’ https://www.arcanum.com/hu/online-kiadvanyok/Lexikonok-magyar-etimologiai-szotar-F14D3/k-F287B/krizis-F2D45/, accessed 15 March 2025. It is clear from this definition that a crisis, according to this original proposition, is first and foremost a decision-demanding situation. Today, however, the interpretation of crisis as a process of decline seems to be coming to the fore: this may be linked to the fact that in modernity the outcome of the decision situations that have been set in motion is generally unfavourable.

[2] Lajos Prohászka, ‘A modern ember’ (‘The Modern Man’), in Prohászka Lajos, Történet és kultúra, (Ed Orosz Gábor), Hamvas Béla Kultúrakutató Intézet, Budapest, 2015, p. 127.

[3] Ibid., p. 155.

[4] Then refers to the period of 19th century positivism and industrial revolution, of expanding capitalism.

[5] Prohászka, 2015, p. 154.

[6] Szilárd Farkas, Nihilizmustól a krizeológiáig. Válságértelmezések a XX. századi magyar filozófiában, MMA MMKI – L’Harmattan Kiadó, Budapest, 2016, pp. 8–9.

[7] Ibid., p. 9.

[8] Rather than using the terms regardig the style of philosophical thought in question, as: ‘traditional school’, ‘traditionalism’ or ‘perennialism’, it is worth noting that the intellectual current was by no means as unified, as some historians of philosophy assume. The idea of a universal or ‘Primordial Tradition’, first put forward by René Guénon—the idea of a spiritual knowledge of the origin and unity of existence, the fragmentation and the variation of which give rise to the various ‘spiritual paths of realization’ and, later, world religions—was in fact already conceived by Plato. It is essential to mention the influence of this intellectual current in the case of Prohászka, since Leopold Ziegler, one of the authors important to him, developed his system of philosophy of religion under the influence of Guénon’s thought. Béla Hamvas, who was also inspired by Guénon (and Evola), was also in contact with Prohászka. It is true, however, that the Catholic Prohászka does not accept many of the fundamental points of Guénon’s and Ziegler’s philosophy.

[9] Béla Hamvas summarizes the thinking that does not live through, trivializes or does not understand the deep structure of crisis in his essay The World Crisis in the following, very apt words: ‘So, when people talk about a crisis and there is a clamor of crisis, something infinitely simple and natural is actually happening: what always happens. Someone has reacted with excessive sensitivity to something that is not exactly favourable. The terms with which they have explained an otherwise not very significant fact have become more serious; the thing has remained what it was, a simple reality. If a comet approaches, they immediately begin to fear the end of the world; everyone knows what mass hysteria took hold in Europe around 1000. It is a peculiar madness! There may be such a reason today, but it is not worth even looking for it. Nothing is ending here, Western culture is not fading away, nothing is going to ruin. The world is changing, but that is its nature. There is no need to be so frantically afraid of what is coming: it will not differ significantly from what is today and what has always been.’ https://mek.oszk.hu/05900/05945/html/gmhamvas0002.html, accessed 14 March 2025.

[10] Prohászka, 2015, pp. 102–103.

[11] Spengler conceived of the ‘Faustian man’ as a specific destiny of the whole European civilization, living under the spell of the conquest of ‘infinite space’ by an ‘archetypical symbol’ and characterized by the activity of the will of material power in all spheres of existence. In this connection, Prohászka wrote in his well-known essay, The Wayfarer and the Fugitive: ‘Wherever we approach the German spirit in its manifestations, in its will to think, in its aspirations, in its actions or in its creations, it opens up the perspectives of infinity in its fundamental idea, in its expression of change.’ (Lajos Prohászka, A vándor és a bujdosó, Minerva Könyvtár, Budapest, 1936, pp. 58–59.)

[12] By this he meant progressionists with a democratic and liberal orientation, and not, of course, communist or national socialist sympathizers. One of the most persuasive and coherent (non-totalitarian) critiques of democracy (and totalitarian democracy as: fascism, national socialism and communism) was offered by the Austrian Catholic political thinker Erik von Kuhenelt-Leddin. See for instance: Liberty or Equality:The Challange of Our Time and Leftism: From De Sade and Marx to Hitler and Stalin.

[13] ‘Embourgeoisement’ can be described as the penetration of cultural forms based on modern natural sciences into traditional popular culture. The ‘civilizing progress’ (Norbert Elias) not only provides ‘an opportunity for social ascension’, but also implies the devaluation of previous forms of knowledge, and the ‘impoverishment of the world’. It is also one of the main factors of cultural levelling, and the loss of economic autonomy in close association with the disappearance of the peasantry, and an increase in the general dependence of people on supply chains.

As Prohászka writes in his essay ‘Culture and literacy’: ‘What is commonly called “fundamental knowledge” can be derived merely from the culture of the individual, undoubtedly not as a kind of summation, but rather as an average. The notion of literacy is therefore in fact a statistical designation. Thus, for example, we judge the average level of literacy in a society by the knowledge of reading and writing or, more generally, by the completion of some degree of schooling. The measure of this judgement is only the external conditions and means of literacy: what one has experienced or, more correctly, what one has been able to experience from culture, but not how one has experienced it. And it cannot be denied that our whole school system today, with its developed apparatus of certificates and diplomas, is based on such a purely external judgement, which only points to the quality and degree of the cultural institutions and how one fits into the average of “public culture”.’ (Prohászka, 2015, p. 290.)

[14] To quote a famous passage by Clausewitz, it is indeed ‘nothing more than the continuation of political intercourse by the interposition of other means’ (Carl von Clausewitz, (1831): Vom Kriege, Dümmler’s Verlagsbuchhandlung, Berlin, 1853, p. 24.), which is proved not only by the failure of the Enlightenment’s plans for ‘perpetual peace’, but also by the fact that the ‘progress of science’ has by no means eliminated war or the threat of war. The cold war that followed world wars is still going on today, according to authoritative geopolitical analyses.

[15] Not all progressivists can be called atheists, of course, but non-atheistic progressivists can rarely coherently argue for progress, since transcendence, when it is seriously considered, implies an element of the irrational or mystical uncontrollable by man, which is in any case at odds with progress that appeals to reason.

[16] Nietzsche first speaks of ‘the death of God’ in paragraph 125 of The Gay Science. The death of God is announced by the madman who lights a lamp in broad daylight to seek God.

[17] Such is the case, for example, of the ontological distinction between ‘being’ and ‘existence’, between ‘phenomenon’ and ‘essence.’ The denial of these distinctions in positivist philosophies: the questioning of ‘metaphysical concepts’ does not, however, mean that the realities which the concepts designate well or badly are thereby rendered non-existent.

[18] As Étienne Gilson puts it in his work on the spirit of medieval philosophy: ‘Moses, in order to know who God is, turns to God himself…There is not a word of metaphysics here, but God has spoken, his voice has been heard, and the Book of Exodus lays down the principle on which all Christian philosophy will now depend…Among all the divine names there is one which is eminently God’s own (Qui est) – nothing other than being itself.’ (Étienne Gilson, A középkori filozófia szelleme, Paulus Hungarus/Kairosz, Martonvásár, 2000, p. 47.)

[19] Lajos Prohászka, ‘A lélek és az Abszolútum’ (‘The Soul and the Absolute’), In: Prohászka, 2015, pp. 7–20, p. 9.

[20] Prohászka, 2015, pp. 484–486. Béla Brandenstein, following Nietzsche, gives a similar interpretation of the modern situation of religion (Farkas, 2016, pp. 36–37).

Read more from the same author: