Modernity in its broadest sense, according to Prohászka, began with the Renaissance and continues to the present day. It is therefore a process that is far from complete, and one which cannot be reversed. The first modern man was, in fact, Petrarch.

‘What makes Petrarch the “first modern man”?…First of all, it is that he breaks free from the transcendent cosmos and stands on his own feet. This self-assertion, the assertion of the soul’s originality, its sole reality in the face of great attachments, the striving to draw everything from the soul and to understand it from the relations of the soul—this is what is typically modern and at the same time epochal in Petrarch’s personality.’[1]

Already in this period one of the fundamental themes can be grasped: ‘modern spirituality’, which in fact means a kind of subjectivism. Petrarch is also the embodiment of ‘spiritual solitude’. Petrarch’s action, ‘This detachment from the great, traditional contexts, this self-absorption of the spirit, however, necessarily makes man lonely in existence. The Middle Ages did not know this spiritual solitude because they did not know existential solitude.’[2]

This disconnection from the big picture is only one side of the nascent modernity. It also includes the ‘versatility of interests’. On the one hand, the soul detached from the great cosmos ‘resonates with everything’ and, on the other hand, it already ‘wants to become a cosmos in itself’—which is ‘the first source of modern man’s restlessness.’ The result: experientialism, immediacy, heightened sensitivity.[3]

‘This detachment from the great, traditional contexts, this self-absorption of the spirit, however, necessarily makes man lonely’

France is the final place of the emergence of modern man. Montaigne’s scepticism appears as a response to Petrarch’s sensibility; it is here that Petrarch’s traits are first associated with the permanent characteristic of modern man: disbelief.[4]

‘His doubt is not deep, but superficial. He takes pleasure in it. The best position is one of neutrality: no one should be offended by his opinions.’ Thus Montaigne becomes ‘the first apostle of modern liberalism.’ The other side is Pascal. Modern man is dizzy with the gaping abysses, for ‘there is no one among us who has not at least once in his life felt the terrifying silence of these “infinite spaces”.’[5]

According to Prohászka, scepticism and pensiveness thus be the attendant of those deeper spirits in modernity who are able to see into the incessantly opening chasms caused by the breaking of the great spiritual hierarchies, the great chain of Being. The so-called achievements of modernity, then, seem to be fully enjoyed only by superficial existences. However, total disbelief is still not Montaigne, but Voltaire: in fact, it is in Voltaire that Prohászka sees one of the most defining archetypes of the modern ‘scientific’ (or rather scientifistic, ‘science-worshipping’) spirit:

‘Fanatical disbelief was unknown at any earlier stage of history—it was born of the modern age. It is that unbelief which not only lacks mystical sensations, but is utterly incapable of comprehending anything beyond the grasp of the senses. And let us not think that this is a one-off or isolated phenomenon. The great masses have generally followed this path. And though religion and philosophy are incessantly struggling against it, we can have no doubt: modern man is generally a man of no faith. Unbelieving from convenience or cowardice, from the abhorrence of enduring the suffering of brooding. Unbelieving from indifference, often from the desire to act out vile instincts.’[6]

Modern man was thus born in the Italian Renaissance and developed in the French Enlightenment. Most importantly, the change (or rather, the rupture) in his relationship with the transcendent: ‘his metaphysical orientation determines all his other expressions of life: the scientific and the moral, the political and the artistic.’[7] The increasing specialization (the basic approach of modern scientific worldview) is also a consequence of this fact. Modern man does not see the Whole. Linked to this is rationalization, which becomes the form of the whole intellectual activity of modern man: reason as a principle. It is most emphatically expressed in Descartes, who ‘lays down the law for all modern thought.’[8] The condition and concomitant of rationalization is ‘predictability’ (Galilei). The cult of predictability, however, leads once again to superficiality, to a failure to sense the ‘essential Being’. Hence the fact that ‘moderns want to reduce everything to a formula, a rational formula…There is no greater stigma than “mystical”.’ [9]

‘Though religion and philosophy are incessantly struggling against it, we can have no doubt: modern man is generally a man of no faith’

The 16th and 17th century manifestation of an exaggerated rationalism is the ‘pursuit of method’ (Bacon) and a ‘heightened sense of reality’.

‘Such an appreciation of reality as the modern age has shown was not to be found either in ancient antiquity or in the Christian Middle Ages. Leopold Ziegler aptly says that facts are the only god before whom modern man still prays.’[10]

From the limitation to material phenomena also follows the position of modern man towards nature: ancient man personified the cosmos, but modern man sees the world as a ‘mere given’. In the modern age, the concept of nature begins to be depersonalized, and the idea of God is also relegated to the background. Modern science wants to explain everything from nature: it denies that phenomena can be expressions of essence. What follows is the most modern age, the ‘age of technology’.

‘If we speak of the modern age, and especially of its last phase, the 19th century, as the age of technique, this age was undoubtedly evoked by the naturalistic outlook of modern man. And even if modern man feels this new power of technology terrifying, far more impressive than the old mythical powers, he is no longer willing to give it up for the advantages it has given him.’[11]

Prohászka attributes to ‘an increased sense of reality’, in addition to technology, the phenomenon in the modern age which he calls ‘the gradual appreciation of human labour’. The modern age values more highly manual work (which the Middle Ages and antiquity, considered unworthy of a free man, even ‘banausic’) because its orientation is positivistic. It is linked to the spread of urban life and the establishment of capitalism, where ‘wider sections of society become workers’. All this brings with it a gradual nivellation of traditional ways of life. Here again, the process is twofold: the universally compulsory nature of work ‘raised modern man to a higher general standard’,[12] but at the same time, by levelling out contrasts, it led to a shallowing of life, of averageness. With the full development of modernity comes a decisive turn in the nature of the appreciation of work: ‘the incentive for work processes to produce results has grown beyond itself.’ Modern industrial capitalism:

‘…has no regard for work as a human vocation. Human labour is a qualitative achievement; profit, on the other hand, is always quantitative. Hence, where profit demands it, it substitutes labour with the machine without any sense of guilt…the labour which liberated men at the beginning of the modern age has, in the course of its development, finally enslaved the great mass of human society to a degree unknown in the Middle Ages, and even in antiquity.’[13]

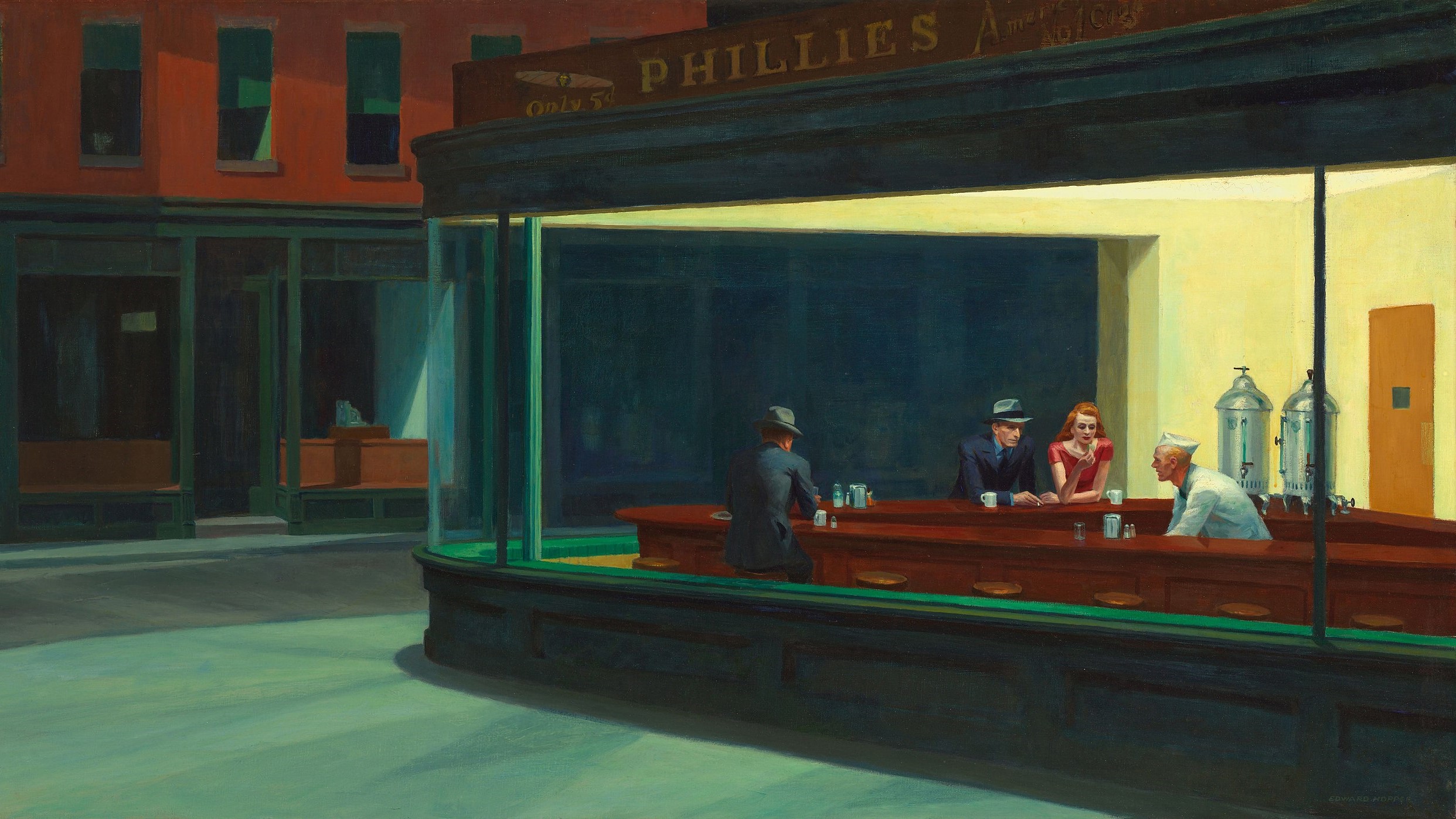

To the extent that modern man is liberated from his former bondage, he is also increasingly bound: even though scientific research is liberated from religious dogma, the conditions of the source research that replaces it are even more severe. The other side of modernity is ‘the gradual increase of mental sensitivity’ which ‘is proportional to the gradual increase of individual responsibility.’ Whereas ancient (and medieval) man was rather objective,[14] modern man is rooted in self-sensitivity—‘modern man does not look upwards, but into himself. He observes and analyses himself, he is reflexive, and therefore, in Schiller’s term, sentimental…The development of the modern novel is a whole line of character poetry, a dissection of soul, emotions and passions.’[15]

It is also paradoxical that the heightened susceptibility to impressions creates in modern man a specific duality: on the one hand, ‘Americanization’ (a hunger for life and factualism), and on the other, ‘impressionism’ (mental subtlety, dreamlike poetry). But the two are nevertheless in contact with each other in their interpretation, regarding the subjectivism of modern man.

In his essay ‘Modern culture’, Prohászka speaks of the four basic characteristics of modernity: it is areligious; technical; pragmatic; and democratic. In addition, according to him, modern culture is characterized by six other concepts: impressionism, lack of conviction, analysis (over-analysis), journalism, artistic (character), and criticism (attitude).[16]

In his essay ‘In the Spirit of Our Age’ he identifies, in a similar way to the above-mentioned study, three basic features: the growth of irresponsibility, massification and industrialism. In particular, a critique of mass accumulation and the closely related industrialism and capitalism is foregrounded:

‘[The masses are] “deaf and blind” to values that are non-hedonistic and utilitarian, to higher spiritual values…This levelling, in which it is the lower values that are decisive, which pull down, like a whirlpool, the higher values…is a process of mass accumulation that is terrifying in its effects, because it mechanizes the whole of life. Mass life…will only exist in loose forms, preferably on rationally calculated and defined tracks…Quality is no more: the spiritless apparatus takes the place of individual initiative, where man himself is no longer necessary. Political life itself is a cliché: dictatorship…it is the spirit of industrialism that has brought it about, and this is the third characteristic feature of our age…But this mechanization and degeneration is different today than it was in the last century: then man used the machine, today the machine uses man. The machine has become a creative force, a world-creator in fact, because it has transformed its world view; a tyrant and a tyrant’s tyrant, constantly demanding human sacrifice. With it, economic production and distribution have been taken out of the hands of human power; the machine commands.’[17]

‘[The masses are] “deaf and blind” to values that are non-hedonistic and utilitarian, to higher spiritual values’

Prohászka describes the social reality of modernity as ‘democratic in character’; and this is as true of modern dictatorship as it is of democracy proper: being both the result of the different ways in which the same principles (the principle of the mass) are politically realized. In his analysis the political reality is rather corrupt—it is almost the furthest from any previous realization of the ideal of the ideal community:

‘The vote of a creative genius is ultimately worth the same as that of a day labourer. The votes are counted and the majority is decisive…in a democracy, the self-government of the people is actually only a theoretical responsibility, while the actual power, as we well know, is usually in the hands of a minority of professional politicians…[From this follows] the entire culture is imbued with the democratic principle, and what is clear from this: its over-politicization…[T]his professional minority seizes every means to secure power for itself by obtaining the majority of votes, which is precisely why propaganda, suggestion, demagogy, and the favouring of selfish interests and aspirations are the usual weapons of democracy. In order to secure power, it brings politics into the state administration, into the practice of law, into economic life, and into school. Finally, religion and art are not spared from it either…People in political life toss from one side to the other like patients on a sickbed, believing that they are lying better.’[18]

Also, in Prohászka’s critique of democracy (and dictatorship), we can observe the manifestation of a crisis linked to the ‘great turn’ of the secularization of man. In his approach to modern science, there has been a turn from the spiritual to the material. What is observed in the spiritual sphere is also at work in the political: an increase in determinism and necessity, a decrease in freedom and individuality. The modern scientific world view, which Prohászka described as an increasing turn away from the medieval hierarchy of the cosmos, replaces the former with a much simpler and more homogeneous world explanation, denying the ontological differences between the ‘spheres of reality’. This is equivalent to democratism, which has conquered the political sphere in both its liberal and totalitarian forms. It conceives of the individual as an atom, without qualitative distinctions: man is not conceived as a Person, with an irreplaceable function, vocation and destiny. In the name of pseudo-equality, ‘everyone’s vote is worth the same.’ To sum up, what is in worldview is atheism; in philosophy anti-metaphysical positivism; in politics, it is Euro–American liberal democracy on the one hand, and fascism, national socialism and Soviet communist ideological manifestations on the other.

There is something that underlies all manifestations—whether these manifestations are decidedly decadent, like political democracy (and dictatorship), or value-neutral, like sensibility growth or impressionism; everything else essentially follows from this shift of emphasis. This is the areligious tone of modern culture. It is from this that all modernity unfolds, and in the background of all distinctively modern cultural phenomena we find the denial of religion and its replacement by the ‘religion of science’.

‘Whereas medieval culture and, as recent research has shown, essentially antique culture, too, was primarily a religious culture, that is to say, religious values prevailed over all other values, and the spirit of religion pervaded all branches of culture, art and state, morality and economic organization, in modern culture it gradually escapes into other cultural spheres and seeks objectification there. Thus, in ancient and medieval culture, state and art, science and morality, law and order and economic organization were predominantly religious; in modern culture, on the other hand, religion itself gradually becomes political and scientific, moral and artistic, and even – as we have already alluded to the connection between Protestantism and capitalism—economic.’[19]

Religion, of course, does not cease to exist in modernity, but it is clear that ‘it has lost its central importance in culture…Its centrality is the mythos atheos’ (Leopold Ziegler) of modern science.

The emergence of modern science, according to Prohászka, essentially means a change of the whole ‘world view and even world situation’: ‘man is regarded as a mere natural product’.[20] In essence, scientism leads to cultural naturalism, and to the modern culture proper: everything else, subjectivism, technicization, and the political consequences: democracy and dictatorship, and massification are only the consequences. Moral decline, or, to put it another way, moral pragmatism is also essentially linked to the great and radical turn of events mentioned above: at some point during the Renaissance (it is impossible to say exactly when or for whom: the turn has a spatial and temporal continuity) something happens that never happened before. The materialistic disposition, the disbelief, breaks through a certain invisible barrier.

‘Religion, of course, does not cease to exist in modernity, but it is clear that “it has lost its central importance in culture”’

But how did this great change occur in the Renaissance? Why and how did man turn away from the transcendent and lock himself into ‘immanent reality’? According to Prohászka, the interpretation of the reality of Christianity is not without fault in this process, which has unintentionally facilitated the process.

‘However much this modern conception of existence may be in direct contrast to the medieval Christian, it is nevertheless based in its development on motifs which are rooted in the feeling of Christian life, the transcendent direction of which, however, modern man has translated into this world, and thus, so to speak, actualized them. Two of these motifs in particular are striking: mechanization and a specific valuation of subjectivity. The mechanizing drive was the driving force behind the acosmistic sense of life of the Middle Ages. This world is not our real home, but only our vale of tears; the Greek cosmic vital sense of life is therefore replaced by a regimental will of Jewish origin: if we belong to this world, the soul must be master of all that represents this ephemeral world, that is, the body, all the mere manifestations of life in general, and our nature. But this inexorable control of life and blood by the power of the spirit, which has found its purest expression in Christian asceticism, has necessarily led to a certain mechanization of this earthly existence. There is no doubt that Christianity, from the very beginning, so to speak, had a vital aspiration which placed this whole existence at the service of a great Telos, the future life, and, above all, freed it from its constraints through the sacraments…but in the sense of medieval life in general, in accordance with the conception of the two worlds, this world of transience remained a lifeless “dead” world, given not to intellectual contemplation but to the working of the sweat of our brow. And where existence is thus subjected to the will, there is no quality, quality is only possible in the other, in the real existence and in the relation of the soul to it, there in fact everything is only quantity, and therefore it must be treated as such. And the modern age continues precisely this quantifying tendency, but again confined to this world, without the transcendent aim of the Middle Ages, with the total abandonment of the qualitative aspect.’[21]

A modern culture based on materialistically oriented science, therefore, represents a cultural anomaly unprecedented in the past. Prohászka also speaks of modernity not as an organic evolution, the result of a natural process of development, but as a peculiar system of relations unlike anything that has been before. Modernity, nevertheless, is, in his view, definitely a culture and not a civilization in the Spenglerian sense. However many parallels there may be, however much comparison with Spengler may be appropriate—especially in the line of criticism of industrialism and massification—, and however much Prohászka agrees with him in rejecting the over-technicalization of modern culture, he is firmly opposed to the ‘culture–civilization dichotomy’ articulated in detail by Spengler. He also rejects Spengler’s view that culture can be equated with creative forces and civilization with rigidity, with technicality.

‘Although we have seen that technology is an essential branch of all culture, without it there is no culture and cannot be a culture, and that it is even earlier in origin than either art or the state. When we say, therefore, that the spirit of technology has overflowed and overpowered us in modern culture, so that the whole of culture has been overwhelmed by technology, we are by no means saying that civilization has prevailed over culture. Technicization is not the same as civilization. Culture, as we have repeatedly argued, is a realized order of values that has become objective. Civilization, on the other hand, is the result of the reflection of this objective order of culture in the human soul, in other words, erudition. A civilized or educated man is one who lives within culture and not outside it, who has received influences from it and can process and develop them. Civilization is not a rigidity, but rather a cultural way of life: by it we express precisely that he who is part of culture is a member of the human or civil community—for culture can only develop in a civil community.’[22]

The question is, if Prohászka saw the phenomena of modern culture as predominantly negative or as fostering negativity, did he suggest a way out of this state of affairs? Beyond merely stating the crisis, what direction did he propose to take? Hamvas, for example, whose analysis of the crisis was akin to his own, found the way out of the modern world crisis in the rediscovery of the pedestal of the Universal Tradition, in the spiritual ‘untangling’ of the desacralized world. Hamvas’s solution to the crisis can be found in the resumption of the ‘basic position’. As he put it in Patmos:

‘Man, since he has stepped off the foundation, cannot find his way home. Europe is adventurous and experimental. Adventure and experimentation are called history. The modern European labyrinthine existence. Tradition has a threefold arc: I know about the founding, about the corruption at the beginning, and about renormalization, that is, the restoration of the lawful and regular order of existence in man, community, nature.’[23]

Hamvas saw in the possibility of a re-appropriation of the basic position, in the re-reading of the sacred books of humanity the antidote to corruption. He believed that it was possible to read sacred books (besides the Bible, for example, the sacred books of Hinduism, the Koran, but also other sacred books, such as the Tibetan or Egyptian Book of the Dead, or the surviving writings of Neoplatonic philosophy) in such a way that their innermost meaning could be understood as correlative content.[24] The sacred books, in essence, are diametrically opposed to modern scientism, and reveal three truths of existence: death is not annihilation, man is not an animal, and God exists.[25] In his view, the contemporary re-embrace of Christian religiosity is not enough: Christianity can only be revalidated or renewed if it corresponds to the archaic (or pre-modern) concept of reality as phenomenon and essence, conceiving of all reality as spirit, in terms of ‘immanent-transcendence’. In his essay ‘Maya’, written in 1946, a year after the end of the Second World War, Hamvas, in the title itself, alludes to the Hindu and Buddhist conception of physical reality: the objective external world, which is commonly regarded as reality, is an ‘illusion’ or ‘magic’, and the only ultimately real being is the only real subject: God. Hamvas argued that the cataclysms of the First and Second World Wars were ‘signs of the times’, as if they were widening rifts in the veil of the world, and that man then gradually, as he progresses through increasingly severe crises, is confronted again with the only reality, which until then had been hidden by the illusion of modern progress.[26]

Prohászka, in his attempt to resolve the crisis, tried to put it on the line of ‘culture–civilization’. He did not focus on a mystical path, on the immersion in the subject, or on the ultimate ‘unreality’ of world and history. Although his study of Leopold Ziegler brought him into contact with Eastern religious philosophy, he incorporated the metaphysics of Hinduism and Buddhism into his own system to a lesser extent than Hamvas. Despite the negative, negationist, atheistic character of modernity, it is important to note that modern culture, according to Prohászka, cannot be imagined as a block—its phenomena and activities are multiple and diverse, and the cultural whole, despite its basic crisis-characteristics, is not such that the consciousness of crisis reaches everyone and everything as one. In fact, only the deepest spirits are capable of perceiving the ‘tragic sense of life’ that characterizes the philosophy of Pascal and Ákos Pauler. Although the modern way of being is extremely tragic because of the denial of immortality, Prohászka did not, or rarely, describe modern culture itself with the apocalyptic images that often characterize Hamvas’s thought.

‘Modernity, despite its distinctness, also draws on expressions of earlier forms of cultural life’

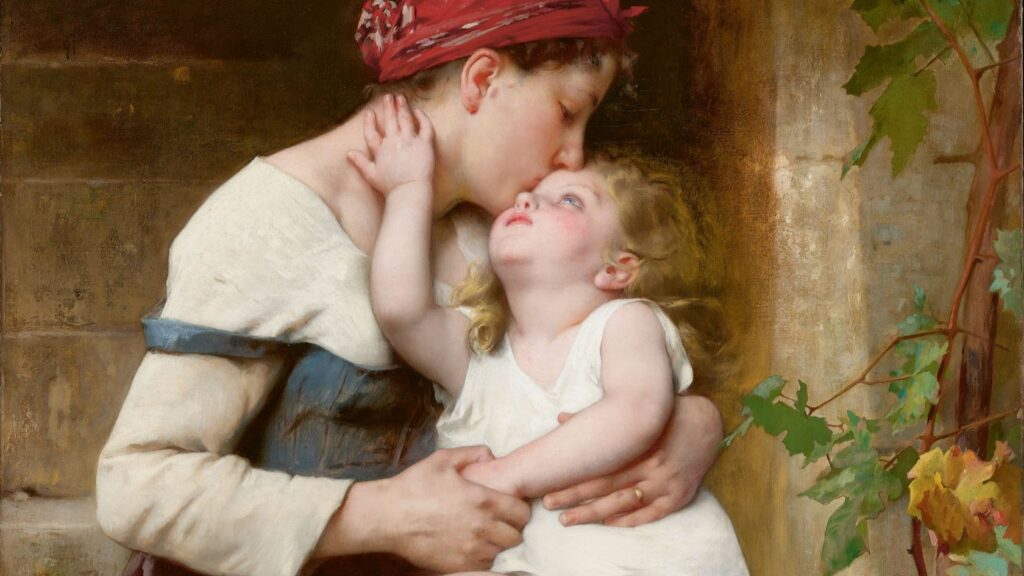

According to Prohászka, in modernity the tradition of earlier, non-atheistic ages does not die out completely, so that modernity, despite its distinctness, also draws on expressions of earlier forms of cultural life. If a positive turn is to be made, this must be grasped first and foremost. Such, first of all, are paideia, the idea of freedom (distorted in liberalism and democracy, but at least present) and the figure of ‘The Humanist’, who rises above the general mentality of the typical modern ‘mass man’. Such an individual represents the ideal community (the idea of community), far above the corrupt social and political reality. In one of his most important essays, ‘The Platonist Cicero’, he is perhaps the most complete exponent of the humanist cultural ideal that defines him:

‘Cicero followed a path for which posterity owes him a special debt of gratitude…Let culture reflect in man the harmony that philosophy recognizes in the cosmos. In other words, we must not develop our humanity according to our own will, selfishly and in our own grasp, but according to the objective order of the world…’[27]

So-called humanism is a concept whose meaning, today, needs explanation. In its communist period, dialectical materialism preferred to call itself ‘humanism’ and ‘humanist values’ are also often foregrounded in the sense of the liberal view of history (or the ‘Whig narrative’ transposed to the present). In these interpretations, humanism means, above all, ‘people-centredness’: this rather nebulous concept is taken to include a wide range of meanings, from simple ‘philanthropy’ to ‘anthropolatry’.

The ‘true humanist’ for Prohászka is, again not in the sense of modern political liberalism, a man ‘liberally educated’ (ie educated on the basis of the medieval liberal arts: artes liberales), who unfolds the human essence in individual and communal excellence and altruism for the betterment of the individual and the community. The character of the ‘true humanist’ is not simply a ‘philanthropist’—although his field of activity does, in fact, include this in regard of the paideia: for the philosopher, who was rather elitist in his outlook, did not reject the possibility of pedagogy (in the spiritual sense), but even elevated it to a high status. The Humanist is linked to the aristocratic spirit of freedom and generosity (liberalitas), whatever the turn it took in later modern political and economic liberalism. In fact, he is not the ‘man-centred man’ of modern (pseudo)humanism, but the ‘God-centred man’ of the antique and Christian traditions. The Humanist cannot be an atheist. Nor is he truly on the ground of modern culture, which Prohászka sees as superficial, quantitative, influenced by both pragmatism and ‘journalism’. The truly educated person is not a specialist, not a master of technical applications, but rather the opposite of the modern specialist, a creative subject with universal thinking, universal education. The antidote to the decadence of modern culture, then, may be, in essence, paideia—in the extended sense—and Ciceronian humanism. Cicero, in his Tusculum Discourse, defined culture as the ‘philosophical cultivation of the soul.’ What is needed is not a political subversion of the societal processes and the mythical atheism of a reductive, materialistic science, but a Ciceronian humanistic attitude.

However unfavourable this age may be to the higher possibilities of the human soul and spirit, it is not a necessity to become a mass-spirit, and people also have the possibility of again acquiring an individual, a cultivated character (in the sense of the philosophical cultivation of the soul). And true culture leads, in fact, to a knowledge corresponding to the objective order of the world: this order, in fact, is the eternal order with which the profoundly perceptive man is never out of touch, an order which is not affected by progress or decline, even if it is not currently realized in the world.

[1] Prohászka Lajos, Történet és kultúra, (Ed Orosz Gábor), Hamvas Béla Kultúrakutató Intézet, Budapest, 2015.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid. 103–104. By ‘sensibility’ Prohászka actually meant both subjectivism, lyricism, and a heightened propensity for depression and pensiveness, as it would appear in the figures of Pascal and Dostoevsky (as well as in the general characterization of the modern novel).

[5] Ibid., p. 106.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., p. 107.

[9] Ibid., p. 108. One might add to Prohászka’s analysis here that the term ‘sense of reality’ may be misleading in this context. By ‘sense of reality’ Prohászka means here, above all, a heightened appreciation of external, physical, objective reality, as opposed to the spiritual and more transcendent orientation of ancient and medieval thought. All this implies a heightened regard for the primacy of empirical facts (or material concretes) in modern thought, as opposed to concepts (abstractions): however, materiality cannot be the definition of reality. The concept of reality, cannot, by definition, be reduced to the domain of physical perception. The reality of ‘thought beings’ also cannot be doubted: the constant objectification of our ideas is proof of this. The reality of ‘transcendental beings’ also depends on their appearance in our experience: just as the reality of ‘dream images’ cannot be entirely doubted—the identification of ‘reality’ with the ‘material exterior’ is a rather arbitrary, illogical concept.

[11] Ibid., p. 109.

[13] It is not clear to us exactly what Prohászka means here by ‘standard’: probably the material standard of living, but he does not specify this. In this respect, looking back from the current phase of modernity, we cannot be at all sure what the material standard of living of premodern man actually was. Generalizations are impossible to make because of the differences in areas and periods, and the lack of data, and looking at modern mass culture, we can say with certainty that the cultural standard of the illiterate peasantry was far higher than that of the average person with a high school diploma in the present day.

[13] Prohászka, 2015, p. 115.

[14] According to Prohászka, this is also proved by the fact that he did not attach much importance to individual and subjective feelings such as love, nor was he moved by hatred to the same extent as modern man is influenced by his desires and feelings.

[15] Prohászka, 2015, p. 119.

[16] Ibid., pp. 121–154. Prohászka’s explanation of the ‘artistic’ or ‘impressionistic’ character is related to the duality of the modern soul mentioned earlier: lyricism, subjectivism and subjectivization are the characteristics of modern art. The foregrounding of subjective feelings (whether positive or negative) in modern culture is common, again a consequence of the ‘secularization of the soul’ which in essence already took place in Petrarch and Montaigne (with different emphases).

[17] Ibid., p. 157.

[18]Ibid., p. 140. As regards the political aspects, Prohászka, in a manner typical of conservatives in general, would, according to the study, have considered traditional monarchy to be more positive. In his study Democracy and Humanism (written between 1944 and 1946), however, he writes somewhat more positively about democracy.

[19] Ibid., p. 122.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid., p. 487.

[22] Ibid., p. 129.

[23] Béla Hamvas, Patmosz II, Életünk Könyvek, Szombathely, 1992, p. 19.

[24] See, above all, Béla Hamvas: Scientia Sacra.

[25] To paraphrase Hamvas’s sarcastically characteristic words from the ‘dogmatics’ of atheistic scientism in his Philosophy of Wine (A bor filozófiája) : ‘The name of atheistic bigotry is materialism. This religion has three dogmas: no soul, man is an animal, death is annihilation.’ Béla Hamvas, A bor filozófiája, Medio Kiadó, Szentendre, p. 8.

[26] ‘Let us not now speak of the shocks which modern man has been forced to undergo, all of which would have occurred only and only in order that man might awaken to the deeper and deeper foundations of his existence, and finally awaken to the deepest, the fundamental…And to think is nothing other than to be convinced that the given world is not real. Humanity’s faith in the reality of the world has today been universally shaken, the conviction that this sensual world is not reality has become universal.’ (Béla Hamvas, ‘Májá’, In: Arkhai, Medio Kiadó, Szentendre, 2012. pp. 171–261. p. 211.)

[27] Prohászka, 2015, pp. 232–233.

Read the previous parts: