This article was originally published in the December 2024 issue of Hungarian Review.

In 1952, at the University of Chicago’s Hillel House, Leo Strauss delivered a series of three lectures titled ‘Progress or Return? The Contemporary Crisis in Western Civilization’.1 The lectures present a remarkable and revealing overview of two fundamental orientations of human beings, and the two elements of the West—Athens and Jerusalem—that most profoundly manifest those orientations; of how modern thought brought about a dramatic shift toward a hope in social progress; how that shift has now become so doubtful; and why a ‘return’ to the thought of the pre-modern West by any serious person must be to one or the other of its two antagonistic roots. I hope to elucidate Strauss’s major arguments.

At the beginning of his talk,2 Strauss first lays out the disposition of ‘return’ by speaking of teshuvah, Hebrew for ‘return’, which also means repentance. ‘Return’ entails a going back from a wrong or sinful way to the original way, the way of one’s ancestors, hence the idea of a perfect beginning or golden age: ‘Originally we were on the right way… Man is originally at home in his father’s house. He becomes a stranger through estrangement, through sinful estrangement. Repentance, return, is homecoming.’3 Orthodox Jews observe still a special Sabbath, Shabbat T’shuvah, just before Yom Kippur. Christians (using metanoia or conversio) have the season of Lent, manifestly a continuation of this Jewish tradition.

But if the right, faithful way is recovered by return, then the origin, the first things, must be well ordered and indeed perfect. ‘The very notion of unfaithfulness or infidelity presupposes that fidelity or loyalty is primary’, as Strauss puts it. ‘The perfect character of the origin is a condition of sin—of the thought of sin. Man who understands himself in this way longs for the perfection of the origin, or of the classic past. He suffers from the present; he hopes for the future.’4 ‘Return’ entails hope for the future, but through renewed loyalty to the original, right way.

The Alternative to ‘Return’, that is, ‘Progress’, Strauss vividly presents as a path for humanity that we today will readily recognize: ‘Progressive man…looks back to a most imperfect beginning. The beginning is barbarism, stupidity, rudeness, extreme scarcity. Progressive man does not feel that he has lost something of great, not to say infinite, importance; he has lost only his chains. He does not suffer from the recollection of the past. Looking back to the past, he is proud of his achievements; he is certain of the superiority of the present to the past. He is not satisfied with the present; he looks to future progress. However, he does not merely hope or pray for a better future; he thinks that he can bring it about by his own effort, [he] lives unqualifiedly toward the future. The life which understands itself as a life of loyalty or faithfulness appears to him as backward, as being under the spell of old prejudices. What the others call rebellion, he calls revolution or liberation.’5

As Strauss adds a little later, the modern notion of progress is bound up with the Baconian/Cartesian turn to technology: ‘[This] idea of progress was bound up with the notion of the conquest of nature, of man making himself the master and owner of nature for the purpose of relieving man’s estate. The means for that goal was a new science. We all know of the enormous successes of the new science and of the technology which is based on it, and we all can witness the enormous increase of man’s power.’6

But since no corresponding increase in man’s wisdom has accompanied this increase in power, the idea of progress has now become ‘a matter of doubt’ throughout the Western world.7 Before explicitly addressing that doubt, Strauss first sketches the content of the idea of progress, starting—perhaps surprisingly, for some of his readers—with the pre-modern version of it, as it manifested itself among the ancient Greeks. Its first requirement is that change be understood as toward the good and not the bad. Its second is that the end of man, the good life, should be understood not as having existed in a golden age at the beginning, but instead ‘primarily as perfection of the understanding in such a manner that the perfection of the understanding is somehow akin to the arts and crafts’, to their development out of a radically imperfect beginning. ‘Accordingly, we find in Greek science or philosophy a full consciousness of progress: in the first place, of progress achieved, and its inevitable concomitant, looking down on the inferiority or the weakness of the ancients.’8 This leads to the expectation of infinite future progress in medicine and the other arts, and even in philosophy, at least in principle.9

Yet strikingly, this consciousness of progress in understanding went together, for the ancients, with a denial of infinite social progress; it went together with a claim concerning the ‘radical difference between laws’, on the one hand, ‘and arts or intellectual pursuits’ on the other, or the recognition of the different requirements of intellectual life and social life.10 But why? The brief reason Strauss gives here is that ‘[t]he paramount requirement of society is stability, as distinguished from progress’.11 But he then makes a crucial additional argument: ‘even the in-principle infinite progress in theoretical matters was thought to be limited, in fact, either by the finite duration of the visible universe’ or by the ‘periodic cataclysms which will destroy all earlier civilization.’12 That is, progress in theoretical matters always included, Strauss implies, for every philosopher, an awareness of what Lucretius called the ultimate collapse of the ‘walls of the world’. And this awareness is unendurable to most men. Modernity’s occlusion of it contributed greatly to its hope for social progress.

For, as Strauss now notes, turning to the modern conception of progress,13 or ‘progress in the full and emphatic sense of the term’,14 a conceived parallel between intellectual and social progress emerges in modernity. It emerges first in a challenge to the ancients’ claim that the intellectual life of science or philosophy is the preserve of a few; ‘method’ would make the results of scientific discoveries open to all; the general increase in intelligence would guarantee a rate of social progress paralleling intellectual progress.15 But an important second claim made by modern proponents of progress concerns ‘the guarantee of an infinite future on earth not interrupted by telluric catastrophes’.16

‘A conceived parallel between intellectual and social progress emerges in modernity’

This guarantee Strauss presents as a ‘hybrid notion’, one that combined admiration of what man had in a short time already accomplished with a great promise or hope of uninterrupted future accomplishments. This guarantee against future cataclysms, Strauss would have us notice, is not based on science, ancient or modern, but on ‘a certain interpretation of the Bible’, specifically, concerning the Noachic covenant—a problematic interpretation of it. For (as Strauss now repeats) the Bible presents the beginning not as imperfect but perfect; it highlights the power of sin and the need for (divine) redemption, over and against progress; the core of the process the Bible presents is neither progress nor an ‘intellectual-scientific development…The availability of infinite time for infinite progress appears, then, to be guaranteed by a document of revelation which condemns the other crucial elements of the idea of progress.’17

It is this ‘hybrid’ character of the modern idea of progress that eventually permitted that idea to undergo what Strauss calls ‘a radical modification in the nineteenth century’.18 He provides, as an example of this modification, a quote from Friedrich Engels,19 in which historical dialectic is presented as ever ascending, from lower to higher. Engels could cling to this notion only by arguing that a finding of modern science, that the earth itself will eventually go out of existence, concerns only the remote future and so not us. As Strauss comments: ‘Here we see infinite progress proper is abandoned, but the grave consequences of that are evaded by a wholly incomprehensible and unjustifiable “never mind”. This more recent form of the belief in progress is based on the decision just to forget about the end, to forget about eternity.’20 The modern idea of progress was sustained not by modern science but by an incoherent adoption of the biblical doctrine of a future guaranteed by God, followed by a decisionist evasion of what had ever been borne in mind by the ancient philosophers. The present crisis of that idea is, Strauss asserts, identical with the contemporary crisis of Western civilization.21 I note that in Natural Right and History Strauss argues that this occluding of eternity is present already in Hobbes’s argument for the sovereignty of man in the universe, that it was extended by his successors, including Hegel, who replaced Hobbes’s conscious constructs with the unplanned workings of history; and that it continues in Heidegger, whose doctrine of Dasein further ‘enhances the status of man’ by dint of this occlusion of eternity.22

Having given this account of the rise of the modern belief in progress, and its most recent iteration, Strauss pauses to recap the necessary components of that belief: ‘Infinite intellectual and social progress is actually possible. Once mankind has reached a certain stage of development, there exists a solid floor beneath which man can no longer sink… [T]hese points have become questionable, I believe, to all of us.’23 And it is here that Strauss points to modern, technological science and its conquest of nature, as well as the increase of man’s power without an increase in man’s goodness, as the most substantial examples of doubt in progress. But the very notion of progress, which has replaced the notions of ‘good and bad’ with ‘progressive and reactionary’, has left us without any ‘simple, inflexible, eternal distinction between good and bad’. That substitution is, he reiterates, ‘an aspect of the discovery of history’, a discovery that ‘is identical with the substitution of the past or the future for the eternal—the substitution of the temporal for the eternal’.24

Strauss turns next to an account of modernity and its crisis, of which the crisis of the idea of progress is a product;25 he provides a thumbnail sketch of modernity. He begins by noting the two roots or ‘elements’ of Western civilization, Greek philosophy and the Bible, and their two differing relations to modernity. He now argues that modernity also adopted from the Bible a certain version of morality26—justice, love of neighbour, charity—minus biblical theology. This has contributed to our crisis. As Nietzsche argued, ‘modern man has been trying to preserve biblical morality while abandoning biblical faith. That is impossible.’27

Turning next to classical philosophy and its relation to modernity, Strauss highlights modernity’s original attempt to replace the old philosophy or science with a new philosophy or science, one that made ‘the same claims as all earlier philosophy and science had done’, i.e. with regard to science being ‘the perfection of man’s natural understanding of the world’. But only a part of the new science and philosophy was successful and indeed enormously successful: ‘Science with a capital S’, such that the new science became higher in ‘dignity’ than philosophy, which became ‘the rump’. Indeed, ‘[s]cience becomes the authority for philosophy in a way perfectly comparable to the way in which theology was the authority for philosophy in the Middle Ages’. This could be so, however, only owing to a general misunderstanding of the nature of the new science, which merely presented (metaphysically neutral) hypotheses that allowed for the given world’s technological manipulation and conquest. This became ‘clear’ to all in the nineteenth century, with ‘the discovery of non-Euclidean geometry and its use in physics’. Modern science then came to be seen ‘as a radical modification of man’s natural understanding of the world. In other words, [modern] science is based on certain fundamental hypotheses which, being hypotheses, are not absolutely necessary and which always remain hypothetical.’28 Nietzsche, again, drew the logical conclusions: modern science is ‘only one interpretation of the world among many’, and not superior to other forms of science, such as Greek science. This development devastated the notion of a ‘rational morality, the heritage of Greek philosophy,’ for ‘all choices are, it is argued, ultimately nonrational or irrational’.29 This concludes the first lecture.

In the second lecture, Strauss addresses in greater detail the two pre-modern ‘elements’ of Western civilization, classical or Greek science and the Bible, in their original agreement and antagonism. He begins the second lecture, though, by revisiting the immediate cause of the decline of the belief in progress: the re-eruption of barbarism in our midst, which empirically refutes ‘the idea of progress, in the full and emphatic sense of the term… [It] is based on wholly unwarranted hopes.’30 Strauss’s contention is that this barbarism ‘is not altogether accidental.’ That is, it has knowable causes, and he now sketches them.

The first of these is the moderns’ turn from ‘ineffective’ appeals to moral principles, ‘preaching, sermonizing’, to effective ‘substitutes’ for moral principles: ‘in institutions or in economics, and perhaps the most important substitute is what was called ‘the historical process’.31 This turn eventually resulted in the fact-value distinction, by two steps. The first was a loss of ‘squeamishness’ about what is conducive to historical progress, or an adaptation to historical trends. The substitution of ‘progressive and reactionary’ for ‘good and bad’ entails an abandonment of the notion of deeds that are malum in se. It thus grants wide latitude to deeds done in the name of historical progress (e.g., the murder of kulaks as a class). The second step is obvious: it became clear ‘that historical trends are absolutely ambiguous and therefore cannot serve as a standard’. At this point, ‘no standard whatever was left. The facts, understood as historical processes, indeed do not teach us anything regarding values … value judgments have no objective support whatsoever’.32

Having provided this initial account of a cause of rebarbarization within the moral course of modernity, Strauss turns briefly to enumerating ‘those characteristic elements of modernity which are particularly striking’.33 The first is a certain notion of human beings and their place in the universe, one that goes together with the technological disposition he had spoken of earlier. The new disposition is not theocentric, as in the Bible and medieval thought, nor cosmocentric, as was classical philosophy, but anthropocentric. This shows itself in modern philosophy, which has become ‘a kind of conscience or consciousness of modern science’. Philosophy turned from causal analysis of the cosmos to ‘analysis of the human mind’—that is, the mind that prescribes to nature its laws: ‘The underlying idea, which shows itself…some places very clearly, is that all truths or all meaning, all order, all beauty, originate in the thinking subject, in human thought, in man.’34 Pursuits formerly called imitative arts are, accordingly, now called ‘creative arts’. By contrast, even atheistic, materialist thinkers of antiquity ‘took it for granted that man is subject to something higher than himself, e.g., the whole cosmic order, and that man is not the origin of all meaning’.35

The second, related modern characteristic is a ‘radical change in moral orientation’, visible in the shift away from the primacy of duties and toward the primacy of (individual) ‘rights’, with the basic right (that is, to life) coinciding with a passion (that is, fear of violent death). Virtue thereby ceases to be ‘a controlling, refraining, regulating, ordering attitude towards passion [and] comes to be understood as a passion’,36 while freedom acquires a radically different meaning: self-construction. ‘The good life does not consist, as it did according to the earlier notion, in compliance with a pattern antedating the human will, but consists primarily in originating the pattern itself… [M]an has no nature to speak of. He makes himself what he is; man’s very humanity is acquired.’37 (The self that constructs its ‘identity’ is the latest iteration of this idea.)38

The third element of modernity concerns a ‘corrective’ of this ‘radical emancipation of man from the superhuman’, one that ‘became fully clear only in the nineteenth century’:39 ‘The so-called discovery of history consists…in the alleged realization that man’s freedom is radically limited by his earlier use of his freedom, and not by his nature or by the whole order of nature or creation.’40 The new (moral) limits entail the alleged insight that it is impossible to ascend out of the historical cave in which one finds oneself thrown as the result of prior free human creative action (Heideggerian ‘guilt’).41 This element of modernity, Strauss notes, ‘is increasing in importance’.42

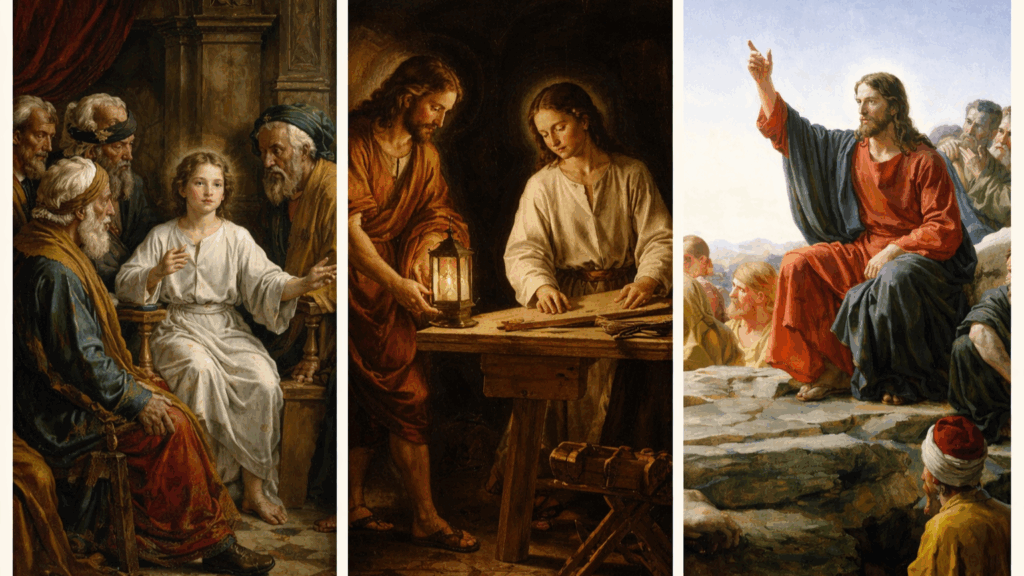

Having sketched these developments in modernity that have contributed to the present crisis, Strauss now floats the suggestion that we might wish to ‘return [to] Western civilization in its premodern integrity, to the principles of Western civilization’. But he presents this path as problematic and indeed impossible: Western civilization is not an integrated whole, since its two elements, the Bible and classical philosophy, cannot be harmonized or synthesized. For ‘[t]o put it very simply and therefore somewhat crudely, the one thing needful according to Greek philosophy is the life of autonomous understanding. The one thing needful as spoken by the Bible is the life of obedient love’.43 Syntheses of these ways of life entail subordination of one element by the other, against its own understanding. This is Strauss’s final argument: the antagonism of the Bible and classical philosophy.

‘Western civilization is not an integrated whole, since its two elements, the Bible and classical philosophy, cannot be harmonized or synthesized’

But before spelling out this antagonism, Strauss first sketches44 the important agreement presupposed in this disagreement, arguing that the classical understanding took seriously the demands of justice and the experience of ‘guilt’ for violations of divine law.45 ‘It is as obvious to Aristotle as it is to Moses that murder, theft, adultery, etc., are unqualifiedly bad.’ Strikingly, biblical and philosophic overlap on the matter of justice includes, Strauss argues, praise of humility, theocracy, patriarchy, and divine law.46 ‘This notion, the divine law, it seems to me, is the common ground between the Bible and Greek philosophy’.47 But, he adds, ‘I must be more precise. The common ground between the Bible and Greek philosophy is the problem of divine law. They solve that problem in a diametrically opposed manner.’48

Strauss will soon present that problem and the two antagonistic solutions, but he first illuminates their opposition by spelling out some of the ‘consequences’ of the antagonism. The Greeks’ ‘philosophic ethics’, he argues, includes two ‘foci’, justice and magnanimity, or ‘noble pride’, both of which foci encompass all the other virtues—one with respect to other men, the other ‘as they enhance the man himself’. The latter, ‘a man’s habitual claiming for himself great honors while he deserves these honors, is alien to the Bible. Biblical humility excludes magnanimity in the Greek sense’. The Bible self-consciously rejects ladies (like Michal) and gentlemen, and the high ‘dignity’ that they claim for themselves. But how or why do the Greeks’ ‘philosophic ethics’ move away from the humility (as well as the elevation of poverty) that characterizes obedience to divine law? ‘Magnanimity presupposes a man’s conviction of his own worth. It presupposes that man is capable of being virtuous, thanks to his own efforts. If this condition is fulfilled, consciousness of one’s shortcomings or failings or sins is something which is below the good man.’49

Strauss illuminates this move by reference to Aristotle’s account of tragedy. Man’s guilt was ‘indeed’, Strauss notes, ‘the guiding theme of [Greek] tragedy’. But the purgation (catharsis) of guilt, achieved by the tragic poet, afforded audience members, Aristotle suggests,50 a temporary approach to what was the day-to-day, permanently purged condition of the man ‘of the highest order’, the philosopher. This famous purging was an exit from what Strauss considers the elemental religious experience—that of guilt, grounded in ‘fear and pity, [of] pity toward him whom I have hurt or ruined and the feeling of fear of him who avenges my crime. [For] God, the king or the judge, is the object of fear; and God, the father of all men, makes all men brothers, and thus hallows pity.’51 Tragic purgation liberates one from ‘morbidity’ and to a life of noble action (though not to philosophy).52 The ‘philosophic ethics’ of the Greeks thus move away from the experience of guilt, the root of ‘religion’.53

This stance toward guilt is often made as a charge against the Greeks: a lack of depth, or a certain heartlessness. Strauss claims that it is born of thought—of ‘the place of man in the universe’. The conclusion of that thought—that God, if he exists, is not concerned with man’s goodness—weakens the disposition of the philosopher toward the concerns of the ‘heart’, just as the opposite belief, in divine providence, strengthens it.54 The Bible thoughtfully nurtures the root of religion, together with what goes with it: humility, repentance, and faith in divine mercy, which ‘complete’ morality and strengthen the ‘majesty of the moral demands’. But those demands have to do with actions on behalf of others in ‘the community of the faithful’, and the philosophic life (as Aristotle argues)55 is a life not of action but of contemplation, an ‘asocial perfection’. Such a life presupposes indeed the existence of political-moral life and of the arts, and hence philosophers considered these to be good—but as a mere means to the (rare) life of contemplation. And as Strauss argued earlier,56 that ‘which supplements or completes morality [is] the basis of morality’, and that is the philosophic life as a life of hard-won serenity.

For as Strauss argues next, the philosopher’s guiding awareness of the absence of divine promises to man results in a ‘serenity’ that excludes, or is ‘above’, the ‘fear and trembling’ as well as ‘hope’ of the believer.57 Elsewhere, Strauss links this philosophic serenity to ‘resignation’, an absence of hope in miracles in the face of human suffering and the eventual destruction of all human things, viewed from the perspective of eternity.58 As Strauss’s subsequent contrasting examples of the prophet Nathan’s upbraiding of David and of the philosopher-poet Simonides’s advice to a tyrant59 make clear, this philosophic serenity includes a remarkable lack of indignation in the face of moral wrongs.60 And whereas the Bible presents Abraham as unhesitatingly obeying an unintelligible command (to kill Isaac), Socrates’s response to an alleged command of Apollo is to investigate its truth.61

But what, finally, are the principles underlying these examples? ‘[T]he Bible teaches creation, implying creation out of nothing. The root of the matter, however, is that only the Bible teaches divine omnipotence, and the thought of divine omnipotence is absolutely incompatible with Greek philosophy in any form.’62 The discovery that moves the philosophers in their understandings against divine omnipotence is the crucial concept of ‘nature’. For, as Strauss now makes clear, ‘nature’ means necessities, impersonal necessities, principles and causes that cannot be otherwise, and above all with regard to first things that are indifferent to human affairs and limit what can be. ‘In all Greek thought, we find in one form or the other an impersonal necessity higher than any personal being, whereas…the concern of God with man is absolutely, if we may say so, essential to the biblical God.’63

But how is it that the Bible and the Greeks arrived at such diametrically opposed principles? Strauss indicates that it is not merely ‘cultural’. To ‘clarify this antagonism’, as he now puts it,64 he goes ‘back to the common stratum between the Bible and Greek philosophy, to the most elementary stratum, a stratum which is common, or can be assumed to be common, to all men’. He goes back, that is—as he does in chapter three of Natural Right and History—prior to the ‘discovery or invention’ of ‘nature’ (as he here evenhandedly puts it). The common, pre-philosophic equivalent to nature is ‘custom’ or ‘way’; that is, the way that classes of things (trees, Philistines, lions) regularly and distinctly behave.65 Most important for any people is ‘our way’, the right way—right because it is old and our own, or ancestral, and hence equated with what is good. The ancestors are superior, and hence ‘gods, or sons of gods, or pupils of gods. In other words, it is necessary to consider the “right way” as the divine law, theos nomos’. And as Strauss now repeats, divine law ‘leads to two fundamental alternatives:’ Greek philosophy and the Bible. It does so due to what he again calls the ‘problem’ of divine law, which he now defines as the encounter with the variety and contradictory character of allegedly divine codes, especially regarding what they say about the first things. What path, then, does each take in this encounter?

The path leading to philosophy is this: ‘[It] becomes necessary to transcend this whole dimension, to find one’s bearings independently of the ancestral, or to realize that the ancestral and the good are two fundamentally different things despite occasional coincidences between them.’66 Philosophy begins with the ‘basic question of how to find one’s bearings in the cosmos. The Greek answer, fundamentally, is this: ‘we have to discover the first things on the basis of inquiry.’ And inquiry entails (first) not accepting the lawful, the hearsay, or the mythical presentations of first things, but instead seeing things with one’s own eyes, and (second) distinguishing what is produced by human art from what is not so produced. This in turn elicits the question of whether the universe is indeed the artful work of a thinking being, God, whose existence must henceforth be established by demonstration.67 Such a being is no longer accepted on the basis of hearsay. It is this inquiry that leads to the discovery of nature. Divine law, the starting point of inquiry, is thus abandoned; it is replaced by a ‘natural order’. ‘And’, Strauss adds, importantly and for the first time, ‘if [divine law] is accepted by Greek philosophy, it is accepted only politically, meaning, for the education of the many, and not as something which stands independently.’68 (Here the exoteric character of the Greek philosophers’ teachings is briefly alluded to.)

‘If [divine law] is accepted by Greek philosophy, it is accepted only politically, meaning, for the education of the many, and not as something which stands independently’

A radically different path to the solution of the problem of the contradictory alleged divine laws is taken in the Bible. Its distinctiveness may be seen initially in the fact that ‘there is no biblical Hebrew word for nature’. Strauss suggests that the intention of the biblical redactors is to foreclose the path of inquiry leading to the concept of nature, and to do so for the sake of preserving the moral life. For in the first place, ‘biblical thought…contends that this particular divine law is the only one which is truly divine law. All these other codes are, in their claim to divine origin, fraudulent… Since, however, one code is accepted, no possibility of independent questioning arises or is meant to arise. ’69

The Bible intends—with admirable foresight—to prevent the raising of questions that lead to independent inquiry and thereby away from the life of trust. This eventually leads the biblical authors to proclaim the radical freedom, omnipotence, uncontrollability, and incomprehensibility of the one God.70 God freely chose, unintelligibly, this people to whom to reveal the true divine code. While God has freely bound himself, through a covenant with this people, and commanded them to perform the covenant, trust in God ‘depends on God’s word, on God’s promise; there is no necessary and therefore intelligible relation’.71 Trust, rather than theoretical certainty gained through autonomous reasoning about necessities, is precisely what the biblical solution aims to achieve. In presenting the biblical God as free and unintelligible, Strauss highlights how the tetragrammaton’s literal Hebrew, ‘I shall be what I shall be’, indicates a perfect freedom, including freedom from intelligibility. The translation by St Jerome is, by contrast, ‘Ego sum qui sum’.72 Natures/necessities mistakenly came, in the scholastic synthesis, to be compatible with creation ex nihilo.

The radical biblical solution to the problem of the contradictory character of the variety of divine codes similarly rejects the ‘mythical solution’.73 For mythology includes the impersonal power of ‘necessity’, another word for which there is no biblical Hebrew. The accounts of creation in Genesis 1 and 2 likewise serve to elevate the omnipotent God and obedience to his commands; they indicate that ‘man is meant to live in childlike obedience’ to God’s understanding of what is good. The well-watered garden into which Man is originally placed, moreover, precludes any compulsion to pursue his own good against the divine commandments. Man’s disobedience, his acting without charity or justice, is not compelled but ‘free’. Man ‘is to be fully responsible’.74 The Bible, to be sure, eventually accommodates the arts, politics, and human knowledge in general, presented originally as rebellions against God, but only on the condition that they be employed in service to God.75

Where does this antagonism leave us, in the face of the crisis of ‘progress’ and of modernity? In his conclusion, Strauss presents the ‘tension’ between the biblical and ancient philosophical understanding not as a cause for despair but as ‘the secret vitality of Western civilization:’ ‘The very life of Western civilization is the life between two codes, a fundamental tension. There is, therefore, no reason inherent in the Western civilization itself, in its fundamental constitution, why it should give up life. But this comforting thought is justified only if we live that life, if we live that conflict.’76 Yet as he immediately makes clear, Strauss does not think that the ‘living’ of that conflict can mean living both of its high components, though it does entail openness to the other way of life and its ‘challenge:’ ‘every one of us can be and ought to be either one or the other, the philosopher open to the challenge of theology, or the theologian open to the challenge of philosophy.’77

In suggesting a return to one or the other of these, Strauss points away from the modern project of progressive enlightenment and toward an individual ascent out of modernity. Neither of the two premodern ways of life, biblical or philosophic, partakes of the modern hope in social progress, nor in the late modern historicism that would confine all thought to its time and place and obscure eternity. The fruitful antagonism of the two pre-modern ways of life stands in sharp contrast to the failed modern synthesis. Especially through his presentation of the philosophers’ serenity, and the Bible’s intransigent demand for justice and hence for a free, unintelligible God, Strauss has quietly brought out the incoherence of the synthesis that modernity represents, its forgetful synthesis. And driving the late modern historicism is a rejection of the one element, philosophy, in the name of the other, morality—anthropocentric, decisionist morality. Strauss points us towards a return to one or the other of the two elements that the moderns vainly sought to overcome: biblical theology or classical philosophy. Insofar as he suggests any ‘social’ rectification of modernity, it is to the biblical—away from modernity’s ‘philistinism’78—but to the biblical ‘openness to’ the challenge of philosophy and its understanding of eternity.

NOTES

1 Leo Strauss, ‘Progress or Return? The Contemporary Crisis in Western Civilization’, in Kenneth Hart Green, ed., Jewish Philosophy and the Crisis of Modernity (SUNY Press, 1997), 87–136. The present essay focuses on the first two talks.

2 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 87–94.

3 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 87.

4 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 89.

5 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 89–90.

6 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 98.

7 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 94.

8 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 94.

9 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 95.

10 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 95; see also Aristotle, Politica, ed. W. D. Ross (Clarendon Press, 1957), 2.8.

11 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 95.

12 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 95.

13 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 95.

14 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 97.

15 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 96.

16 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 96.

17 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 97.

18 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 97.

19 Friedrich Engels, ‘Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy’. Strauss provides (on page 97) his own translation from the text of Ludwig Feuerbacb und der Ausgang der deutschen klassischen Philosophie. No edition is cited. Kenneth Hart Green (on page 133, note 17) provides the following reference to the original German text: Karl Marx und Friedrich Engels: Werke, Institut für Marxismus-Leninismus beim ZK der SED, vol. 21 (Dietz, 1962), 267–268.

20 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 97. (Emphasis added.)

21 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 97.

22 See Leo Strauss, Natural Right and History (University of Chicago Press, 1953), 175–176. Footnote 10 on page 176 contains the original German of the passages from Engels’ Ludwig Feuerbach und der Ausgang der deutschen klassischen Philosophie that Strauss had translated in ‘Progress or Return?’, 97.

23 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 98.

24 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 98. Consider Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, Parts III, IV, and V, transl. Joan Stambaugh (SUNY Press, 1996), 279–369.

25 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 98.

26 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 99.

27 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 99.

28 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 99–100.

29 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 100.

30 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 100.

31 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 101.

32 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 100.

33 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 100.

34 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 102.

35 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 102.

36 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 102.

37 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 103.

38 See ‘Perspectives on the Good Society’, in Liberalism Ancient and Modern (Basic Books, 1968), 261–262.

39 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 102.

40 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 102–103.

41 See Heidegger, Being and Time, 262, 264–265.

42 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 102.

43 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 104.

44 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 105.

45 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 108. See also On Plato’s Symposium (University of Chicago Press, 2003), 265; and Laurenz Denker, Kerber Hannes, and David Kretz, ‘Leo Strauss’s “Jerusalem and Athens”: Three Talks Delivered at Hillel House, Chicago (1950)’, Journal for the History of Modern Theology/Zeitschrift für Neuere Theologiegeschichte, 29/1 (2022), 146: ‘a sense of shame […] as Aristotle uses it, corresponds exactly to what is called in the biblical tradition feeling of guilt, of repentance, of sin, and so on.’

46 Strauss adds here that the Bible and Greek philosophy ‘also agree regarding the problem of justice’, which he then defines as ‘the difficulty created by the misery of the just and the prospering of the wicked’, providing as examples Glaucon’s description of the suffering of the just and Isaiah’s and Job’s similar descriptions, and the similar restorations (106). This problem, the problem of justice, is not further elaborated upon here. It appears to be different from what Strauss will soon call ‘the problem of divine law’.

47 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 107.

48 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 107.

49 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 108.

50 See Aristotle, Peri Poietikês, in Aristotelis Opera, Vol. 11, edited by Immanuel Bekker (Oxford University Press, 1837), 1453a7–11 and 1449b24–28.

51 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 108.

52 As Strauss will soon argue (109), the philosophic life is a life of ‘asocial perfection’. And as he indicates on page 108, the soundness of the magnanimous man’s self-assessment was questioned by Socrates.

53 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 108.

54 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 109.

55 See Aristotle, Ethica Nicomachea, edited by J. Bywater (Clarendon Press, 1894), 1177a13–1179a33; cf. Politics, 1255b, 1259a, 1267a, 1324a.

56 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 105.

57 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 109.

58 See, for example, Strauss, What Is Political Philosophy? and Other Studies (The Free Press, 1959), 28; ‘Social Science and Humanism’, in T. L. Pangle, The Rebirth of Classical Political Rationalism: An Introduction to the Thought of Leo Strauss: Essays and Lectures by Leo Strauss (University of Chicago Press, 1989), 7.

59 In Xenophon’s Hiero, on which Strauss had published his first book on a Greek thinker.

60 See also Plato, Politeia, in Platonis Opera, edited by John Burnet (Oxford University Press, 1903), 347d; and Apologia Sokratous, in Platonis Opera, Tomus I: Tetralogia I-II, edited by John Burnet (Clarendon Press, 1905), 32e.

61 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 109–110.

62 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 110.

63 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 110–111.

64 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 111.

65 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 111–112.

66 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 113.

67 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 113–114.

68 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 114.

69 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 114. (Emphasis added.)

70 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 114.

71 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 115.

72 Using this translation, Thomas Aquinas takes God’s name to signify the essence or ‘nature’ of God as his being, and presents creation as the creation of natures. Summa Contra Gentiles (Marietti Editiori, 1961), I.22.9–10, with Summa Theologiae (Marietti Editori, 1962), I.13.11.

73 This is more fully elaborated upon in the third talk, on page 119.

74 ‘Jerusalem and Athens’, Jewish Philosophy and the Crisis of Modernity, 371–372, 385.

75 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 116.

76 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 116.

77 Strauss, ‘Progress or Return?’, 116.

78 See 91–92, together with Strauss, ‘Perspectives on the Good Society’, in Liberalism Ancient and Modern, 272.

Related articles: