This article was published in Vol. 3 No. 4 of our print edition.

Nation as Interpretive and Complete Community

Although the concept of the ‘nation’ has somewhat different meanings in Central Europe and Britain, it is fundamental to deal with it if we are to try to grasp what kind of interpretive framework is referred to by conservatism. In his famous book, England and the Need for Nations, Scruton gives the basic reason why ‘nation’ is so unavoidable in the community-building process when ‘trust between strangers’1 has to be established: ‘Accountability to strangers is a rare gift, and in the history of the modern world only the nation state, and the empire centred on a nation state, have really achieved it’.2 There are more conditions of the first-person plural—tribal or creed communities—that can minimize the risk of social disintegration, but the nation is the only one that meets the requirements of the modern body politic: ‘Nationality is not the only kind of social membership, but nor is it an exclusive tie. However, it is the only kind of membership that has so far shown itself able to sustain a democratic process and a liberal rule of law.’3

According to Scruton’s arguments, which are convincing, ‘Panglossian universalism’4 and the supporters of transnational organizations, or the compulsive proponents of the world state, suffer from ‘oikophobia’, by which he means ‘the repudiation of inheritance and home’.5 We must ascertain that not only the British political identity ‘has entered a state of crisis’.6 What Scruton declares can be perceived worldwide: ‘This crisis has come about because the loyalty that people need in their daily lives, and which they affirm in their unconsidered and spontaneous social actions, is constantly ridiculed or even demonized by the dominant media and the education system. National history is taught (if it is taught at all) as a tale of shame and degradation. The art, literature and music of our nation have been more or less excised from the curriculum, and folkways, local traditions and national ceremonies are routinely rubbished.’7 In Scruton’s philosophy—and he elaborates it in other books, e.g. in the Fools, Frauds and Firebrands: Thinkers of the New Left—the social practice of legislation and jurisdiction could not be realized outside the national framework, because—regardless to their origins—the interpretation and the enforcement of the set of legal rules and moral duties, even human rights, are bound to nation states:8 ‘When embedded in the law of nation states, therefore, rights become realities; when declared by transnational committees they remain in the realm of dreams…’9

The cultural pattern of the common law is regarded as a main component of conservative thinking. Russel Kirk describes William Blackstone’s book, Commentaries of the Laws of England, as one of the four pillars of the British cultural heritage that have formed the American culture.10 In Kirk’s view—referring to Burke, T. S. Eliot, and Thomas Molnar—‘culture’ is a whole tradition that involves customs, taste, and spirit. Nation, in this point of view, is the community which is carrying on that tradition.11 Surprisingly, famous intellectuals in previous eras of Hungarian history repeatedly mentioned common law as an ideal way of thinking about the continuous, uninterrupted operation of cultural tradition.

However, it may be surprising for foreign researchers that the distinction between pro-national and anti-national attitudes is more relevant than distinguishing between the right and left in Hungarian intellectual history. There are many leftists (e.g. László Németh) standing for a pro-national attitude who can be deemed allies by Christian pro-national intellectuals. The question of the viability of national thought has been on the agenda since the term emerged. There is ample literature on the issue suggesting that the signifier of cultural nation—I use the concept in a cultural rather than an ethnocentric or legal sense—is neither identical to the definitions of the political nation and the body politic, nor to society and state (in the English terminology the government).

In any event, the nation is a specially developed cultural community that can be characterized in various ways. Stanley Fish’s term, the authority of interpretive community ‘sketched out an argument by which meanings are the property neither of fixed and stable texts nor of free and independent readers, but of interpretive communities that are responsible both for the shape of a reader’s activities and for the texts those activities produce’.12 His literary theory—contrary to the formalist New Criticism—assumed that ‘it is not that the presence of poetic qualities compels a certain kind of attention, but that the paying of a certain kind of attention results in the emergence of poetic qualities’.13 This approach affected by the speech act theory—introduced by Oxford philosopher J. L. Austin—prefers the reader’s accustomed pursuit, ‘the acts of recognition’ or ‘the common-sense intuition’ instead of the self-referential aesthetic object. Literary texts are as much social and conventional productions as legal texts.

The approach of Fish is very similar to that of Herbert Hart who introduced the ‘rule of recognition’,14 a master meta-rule which—among other functions—establishes a test for valid law in the applicable legal system, telling us what counts as law. This ‘secondary rule’ is mostly not written down, but is deduced from the deeds of official lawyers. Meaning is a ‘culturally derived interpretive category’, therefore it is true that ‘readers make meanings’, but its opposite is also true, ‘meanings make readers’.15

‘The political switch included mental stimuli generated by “formal justice” called rule of law and “material justice”…which is constituted mainly in the realm of literature’

Looking for the specific conditions of such a community, we may turn to the Thomist moral philosopher John Finnis. He examines the types of ‘unifying communities’ (family, friendship, play, and business communities), and identifies the so-called ‘complete community’ among them.16 Over family, economic, cultural, sporting associations, and friendship, ‘there emerges the desirability of a “complete community”, an all-around association in which would be co-ordinated the initiatives and activities of individuals, of families, and of the vast network of intermediate associations’.17 Finnis adds to that given definition that ‘there is no aspect of human affairs that is outside the range of such a complete community’,18 whose paradigmatic form—for Aristotle—was the Greek polis. This community implies politics and legal systems, the latter ‘claim authority to regulate all forms of human behaviour’. However, the complete community as modern state is not complete at all, hence the order of the international community is indispensable. Finnis—contemplating from a universal religious horizon—concludes that ‘the claim of the national state to be a complete community is unwarranted and the postulate of the national legal order, that is supreme and comprehensive and an exclusive source of legal obligation, is increasingly what lawyers would call a “legal fiction”.’19 Although it is unquestionable that increasing interdependence and intercommunication justify the need for an international community—e.g. in a Kantian manner, as suggested in Zum ewigen Frieden—the realization that the nation state is not a self-sufficient system of values does not entail the elimination or invalidation of the nation. Only the good order of individual nations can create the good international order, which is named by Kant ius cosmopoliticum.

The Development of Nation

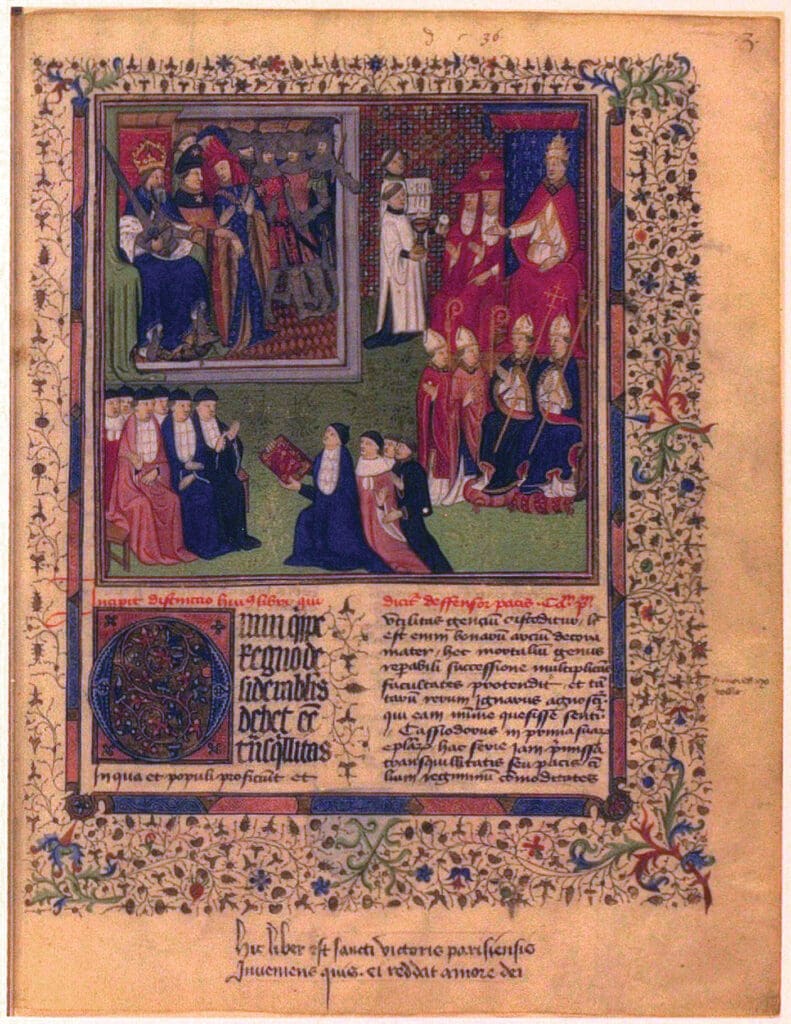

It is a key concept for me that everything we understand as human dignity can only be protected here and now inside the cultural framework of the nation. Most of the values belonging here and defining our European character were not born within this national framework because the Greek polis, the Roman Empire, the medieval Christian kingdoms, the Regnum Italicum which gave birth to our ideas of the European individual, religion, art, history, freedom, or the organization of the state in their soul-cultivating endeavours, did not know the modern idea of nationalism. Moreover, we bear in mind that a national culture must never be isolated from other national cultures; its intrinsic attributes are openness and curiosity. The Foundations of Modern Political Thought—the great inquiry of Quentin Skinner—shows us how the conquering, competing, and reconciling ideas of ‘regnum’ and ‘sacerdotium’ formed the conception of temporal and ecclesiastical power in Europe in the Renaissance and in the age of Reformation.20 The humanist universalism and critical way of thinking have remained a common heritage. Against ‘the underlying idea of a separate and privileged clerical estate’—according to the earlier doctrine of Marsiglio of Padua—a kind of ‘nationalist hostility’ is to be found in England in the fifteenth century. The cause of this legal interference is the history of England, ‘where the Roman code of law was never in force, and where the claims of the Papacy and the canon lawyers tended, in consequence, to conflict most radically with the demands of common law and the enactments of Parliament’.21

The development of nations has been a long process. This process has had a European perspective in which the Christian philosophies and the Enlightenment as a system of ideas are intertwined. As a guarantee of its life, the nation should never turn inwards, but should be ready to absorb and assimilate foreign influences. We must emphasize accordingly that the European Union—even in the given circumstances, or especially because of them—is the primary prerequisite for the existence of our specific cultural codes. There are no other real alternatives—neither supranational organizations, transnational institutions nor multinational corporations—worked out for us to avoid global value degradation. Otherwise, the devastating earthquake of mass culture and the global uniformity of commercial exchange will cause the collapse of European political identities.

Most believe that the nation is the enemy of the strongly appreciated practical reasonableness and dialectical or topical debates. In their opinion, the national framework is inconsistent with the operation of a democratic public. Based on this premise, truth can be constituted by scientific means or by deducing from a set of arguments derived from the rationality of the lifeworld, in the sphere of a universal moral philosophy. While it is absurd to expect national commitment from the scientific method, as we see now, trust in logical argumentation, the scientific worldview, and the reliability of scientific research are being eroded in proportion to the decline of statutory control and national traditions. If the remnants of a state’s bureaucratic functions deteriorated to the point of advancing the dissemination of mass culture, having promoted group interests without national commitment, freedom of research and academic autonomy would not be guaranteed at all. Likewise, while an artwork is not beautiful or authentic because its artist is a member of a specific nation, and a political argument is not convincing because it comes from the mouth of a member of a specific nation, an artwork seeking universal validity by breaking away from national traditions can only be described as a mass product, and a political argument not serving a specific community is at best a matter of indifference, or at worst a means of exceeding usual rates of profit.

I would not conceal the fact that this image of the nation is fundamentally aristocratic; it imagines the nation favouring a quality—realizing the ‘revolution of quality’, as a Hungarian writer, László Németh puts it22—which is not obvious at all. Today the essentially quality-oriented national principle is often confused with the quantitative principle of the democratic majority, which is crucial for some cases, but not the same thing. While it is not true that beauty is what the majority of mankind loves, it is also not true that beauty is what the majority of a nation’s members adore. The post-Marxist approach to culture, which converts the political community into an arena of emancipatory battles, and heralds—in Roger Scruton’s phrase—the arrival of the ‘culture of repudiation’,23 has its national equivalent when certain popular topics and issues supersede qualitative critical examination. The point is that young generations nowadays are susceptible to cyber-Leviathan chaos without any constraining connectedness to a national identity.

Organic and Critical Periods of History

The progressive concept of the nation—admittedly oxymoronic—is the prerequisite for the common good in the worldview of political identity. Jan Patočka—and citing a Czech philosopher is no coincidence—construes the concept of human development as an alternation of organic and critical periods. This distinction goes back to Auguste Comte’s positivism.24 Comte was not the first to make the distinction, although it is him that Patočka cites. Since his appearance, Western civilization’s community-forming mission—or, as István Bibó puts it, ‘the meaning of European social development’25—has been regarded as a transition from the organic to the critical era, and we endeavour to discover the new or restore the organic period that has been lost.

A schism developed between those who see the loss of the organic community as a tragic rupture in tradition and those who see the assumption of the ancient organic way of being as a false consciousness that is a fatal setback for progress: it can be referred to either in the realm of fantasy or in the distant future. Those taking up a position at one end of this imaginary axis portray an archaic or patriarchal ancestral state, a time of grandeur remembered as a golden era which was wiped out at some point, perhaps at the start of the shift to modernity. On the other hand, the fact that the organic period’s ideology is considered a repressive power formation may be driven by class (communism) or gender (feminism or radical LGBTQIA-activism), among other factors. On the one side are the believers in organic naturalness and righteousness, while others assume that history’s teleology is the elimination of the organic period’s oppressive tendencies, such as feudal vestiges, commodity fetishism in capitalism, or the phallogocentric worldview that subjugates women in the struggle for institutional dominance. Utopian social engineering may one day result in a genuinely organic era when the state goes away, an ideal society is created without class differences, or an ideal community emerges that transcends conventional binary gender norms.

Returning to his train of thought, Patočka associates the organic with a condition of balance, though without specifying whether this was of natural or artificial origin; ‘organic’ was rather identical with the status quo for him. He offers Jan Masaryk as an example of someone who, following the fall of theocratic governments—as a consequence of the First World War—recognized the victory of democracy as the new condition of balance. On the contrary, and almost simultaneously, Max Scheler identified democratic equalization as the source of decline and the reason for disequilibrium; nevertheless, he eventually amended his position to find equilibrium in the harmony of ancient metaphysical heritage and the current democratic status. In this framework, the nation as a substantive category is a sheer anachronism with which current democratic public opinion cannot deal. This is undoubtedly the Achilles’ heel of social theories using nationalism as a key notion today.

‘Nation’ is an overwhelmed concept in and of itself, but it is just as overloaded as, say, democracy, capitalism, or the rule of law. Those theorists who believe it to be an organic entity rooted in medieval history or anthropological considerations—this belief became widespread in our country through the impact of German idealism (Fichte and Herder)—perceive external criticism of their own vision as a kick against Providence, and therefore a metaphysical sin. Those who believe that the nation is a construct of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century elites, on the other hand, urge that the new contemporary state and social order transcend its antiquated value systems and move beyond its intellectual frame of reference. This is the conclusion that the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas draws, conceptualizing the ordinary trajectory of history as moving from ‘ethnos’ to ‘demos’, from blood alliance to ‘constitutional patriotism’.26 In other words, the organic period of nation has finished, and democracy is the new settlement, to use Patočka’s terminology. Aside from the fact that Habermas’s social philosophy has become increasingly difficult to justify in many ways, the description and normative substance of the nation’s existence is no more self-evident in the twenty-first century than it used to be.

‘Having experienced the weaknesses of liberalism, our dilemma is to avoid sheer decisionism and not to become doctrinaire’

We must not claim to speak on the basis of a discovered truth if preconceived value conflicts are to be resolved. It is an intriguing historical-philosophical problem whether a nation is a kind of organic order, a form of community complying with natural law and human nature, fitting into the divine history of redemption, or a modern, arbitrary construction; even the beginning of its formation is not clear. I myself would not make any strong statements about it. It is apparent that the nation is based on biblical, ancient, and medieval myths, concepts of theology, and the philosophy of law and its intellectual outputs have been heavily criticized in the history of ideas since its theoretical elaboration and political success emerged.

When János Erdélyi, a Hegelian philosopher in Hungary, limited national thought to emotionally constrained literature and contrasted it with the cognition of universal cosmopolitan philosophy,27 he narrowed the scope of its achievement in the same way as Alexander Bernát, another philosopher, in the last decade of the nineteenth century, who separated the defence of national spirit from aesthetic intensity.28 The country chosen as an example in Yoram Hazony’s book The Virtue of Nationalism is still anchored in the Old Testament and tribal foundations. In his theory, many issues are raised. He proposes the nation as the only viable option to avoid two types of danger: anarchy and empire.29 However, our Central European way of life necessitates a different idea of nation than his image, which alerts us to the fact that our task cannot be done by anyone else. ‘To be Hungarian is a question of commitment, not of origin’, wrote Hungarian writer Gyula Illyés. The ideology of liberal nationalism in the nineteenth century is said to be the climax of Hungarian intellectual history. István Széchenyi, József Eötvös, Ferenc Deák, and Zsigmond Kemény were able to reconcile the ethnic pursuit of the minorities and Hungarian national modernization. Nation and modernization, homeland and progress, seemed incompatible as that ideology became exhausted, symbolically from the time of the poet Endre Ady’s appearance. Although more and more people—both in political philosophy and literary history—argued that the dichotomy of ‘nation and modernization’ could not be fitted in one single programme, the most outstanding thinkers insisted on doing just that. These discussions erupted during the regime change in 1989; they set the nation on fire, consumed it, and we have been waiting for the political community to emerge like a phoenix from the ashes ever since.

The Normative Universe of Central Europe

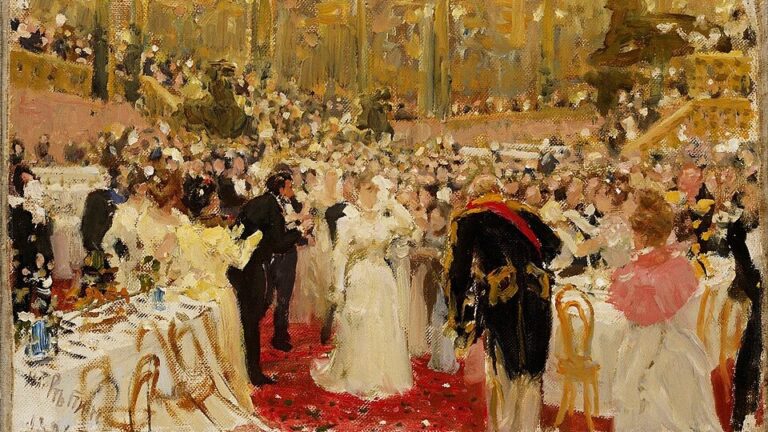

We owe it to ourselves to define our national image, rearticulate its conception, and preserve our modern political identity in the twenty-first century. But how did we start it, or, more precisely, how could a project like this have been started? In his famous book Die Kultur der Renaissance in Italien, Jacob Burckhardt assumes that the developments of art and state are related.30 High-profile artistic value entails political requirements, and the state itself is a piece of art. Similarly, Stephen Greenblatt notices that ‘we can fruitfully grasp the “recursive character” of social life and of language’, that of history and discourse. There appears to be a ‘single realm’ that ensures ‘the oscillation between totalization and difference, uniformity and the diversity of names, unitary truth and a proliferation of distinct entities’ which ‘is built into the poetics of everyday behavior in America’.31 Hungary lost sovereignty in 1944, when it was occupied by the Nazi Germany. After the subsequent Soviet occupation, having acquired constitutional self-determination, the country faced not just economic and legal problems, but also a more essential one about self-knowledge. Consequently, the establishment of the sovereign Hungarian state, or, as researchers frequently refer to it, ‘the third wave of democratization’, was also a cultural project initiated and codified in the literary artworld as much as in the field of law.

From my point of view, and it is the standpoint of a conservative, the problem is hostile to the procedural approach of ‘transitology’, which ignores the different social contexts, and shares the normative belief concerning the matter, which is of a neoliberal nature. In my opinion, the political switch included mental stimuli generated by ‘formal justice’ called the rule of law and ‘material justice’ (or substantive justice) which is constituted mainly in the realm of literature. These two spheres may have been cooperating in order to maintain the political identities not only of the Hungarians, but also of all Central European bodies politic. We may conceptualize Hungarian democratization using categories adaptable both to the realms of politics and art, relying on such cultural phenomena as elite participation strategies, ‘collective memory’ (by this, I mean the Halbwachsian collective memory), customs, attitudes, behaviours, and habits. This is the method by which we can recognize the nation’s political identity. I use the term ‘formal justice’ with the meaning of a set of rules that stand for the doctrine of legality, an ultimate reference for general, clear, and durable prescriptions. However, the determination of the principles of political morality must be extended beyond the limits of law and order without jeopardizing its validity. In this sense, ‘material justice’ is a complete programme for social justice that does not restrain the doctrine of rule of law, but operates as an amendment for the predictable interpretation of its provisions. Hungary as a political community had to bear the burden of freedom and needed to find out the meaning of the nation in the postmodern era. Hungary was faced with this problem, rooted in modernity, while Western countries were influenced by postmodern political thoughts, and the project of European integration was in progress.

In 1989, the Hungarian body politic could have recognized a double-sided problem. First, the legal framework of freedom was created by the new constitution in the sphere of legislation. In addition to this, a coherent interpretive (or textual) community should have been reconstituted in order to concede a shared epistemology, cultural code, system of beliefs, and narrative structures about the memorable events of the past and future plans. Both challenging tasks are interdependent, being parts—or subsystems—of the ‘normative universe’. These two spheres together constitute the so-called ‘nomos’. The idiom of Nomos, formulated by Robert M. Cover, means ‘a present world constituted by a system of tension between reality and vision’.32 According to this concept, law is merely a social construct, its meaning created not only by professional lawyers, but also by the practice of those particular groups, movements, and intellectuals who reveal the inhabited social order of right and wrong, predominating or deteriorating continuously. Cover’s famous proposition is the following: ‘For every constitution there is an epic, for each Decalogue a scripture.’33 The oscillating motion between the sphere of valid and void describes a core image that is shared by both literature and law.

Genuine community involves an interpretive community of law and literature. Historically, every spiritual movement or atelier which has affected the contemporary reception and cultural codes of literature has characterized itself as ‘counter-cultural’. The coherent and elevating vision of ‘nation’ and ‘modernization’. Jan Assmann introduced the terms ‘counterpresentic myth’ and ‘counterpresentic narrative’ in which collective memory opposes the present and resists the prevailing cultural authority by fabricating counter-narratives.34 We may conclude that the narratives that appeared in the Hungarian literary artworld in the twentieth century were vehemently and permanently challenging the officially codified ones. Literary narratives followed the same pattern after the Hungarian Revolution in 1956. Later on, the Prague Spring in 1968 and Polish Solidarity in 1980 gave another boost to their formation.

After the Revolution of 1956 was put down, it became a taboo. The regime considered it the most dangerous one besides two others: namely the social status of Hungarian minorities living in the neighbouring countries and the issue of Hungarians living in exile. It is notable that the revolutionary atmosphere emerged from the revolutionary innovation of the poetic language (e.g. László Nagy), plays (e.g. Gyula Illyés), novels, and films. The new dictatorial rule took various measures in order to repress it: some writers—especially those who had formerly been considered ‘loyal’ and who later became ‘traitors’—were arrested; others were discredited. Consequently, many strategies were established in the belletristical artworld that facilitated speaking about the so-called ‘sorrowful events’ without mentioning them explicitly. Moreover, ‘1956’ was put at the centre of collective memory. It was the main goal of the dictatorship to twist the truth and falsify the common narrative about the Zeitgeschichte, while writers were obviously committed to putting forward a counterpresentic narrative and creating an alternative normative universe in the shadows of intimidation and censorship.

The memory of 1956 played a central role later on, in the democratization period and the body politic’s new constitution, with judgments and debates over the credibility of all opposition strategies that tackled the ‘unspeakable’. In the absence of civil society, writers—mainly poets (Ágnes Nemes Nagy, János Pilinszky), novelists (Géza Ottlik, Miklós Mészöly) and essayists (Sándor Csoóri, György Konrád)—but also filmmakers (Miklós Jancsó, Sándor Sára), painters (the Zuglói kör or Zugló Circle), actors (Zoltán Latinovits) etc., maintained the continuity of the collective memory of national culture in the public domain. Given that there was no officially permitted institution, groups of writers were competing to determine the dominant opposition doctrine and narrative. Without elaborating on historical backgrounds or excavating their spiritual roots, I merely claim that there were two distinctive opposition groups preparing and later executing the democratization process.

The Hungarian Democratization

The common features of the opposition groups were manifested in the insistent claim for political pluralism, transcontextuality, and teleologicity. I mean by transcontextuality that the context of a text or speech incorporates multiple discourses, views, and disciplines. Writers played a prominent role in ‘social engineering’ through their essays, poems, and novels in a teleological way. However, they had no choice in that matter. Writers seemed to have an influence on the formation of the new interpretive community and political agenda. New narratives, values, scenarios, and ideas were scrutinized in the dictatorship’s tolerated or forbidden intellectual forums. Both originated in the thoughts and moral resistance of István Bibó, philosopher and essayist, the only revolutionary leader who stayed in the Parliament building when the occupying Soviet troops were about to arrive.

Bibó’s philosophy synthesizes two components: as a philosopher of law, his reasoning is embedded in the universalist character of formal justice, and as an intellectual, his essays explain the peculiarity and particularity of Central European social development which concerns material justice. This is the point that Milan Kundera explores in his famous essay A Kidnapped West: The Tragedy of Central Europe (1983).35 According to him, this region is a ‘Kidnapped West’, hence in its special development the word ‘culture’ means a more traditional, horribile dictu heroic form of life. Civil participation emerged from elite cultural practices instead of free mass media, which is a phenomenon that had been strongly affecting cultural codes until recently. Bibó’s emblematic figure initiated the famous Bibó-emlékkönyv (István Bibó’s Memorial Book, released as samizdat in 1980),36 an anthology in which prominent writers and sociologists wrote about their spiritual and moral relation to the great ancestor who died in 1979.

Authors in the literary artworld can be categorized according to whether they concentrate on the success of institutional standards or emphasize the substantive implications of material justice. Differences might be identified in three fields: (1) the usage of publicity; (2) epistemological premises; and (3) preferred poetic devices and genres. Universalists who mainly rely on universal social institutions interpreted the Revolution as a fight for human rights. This is the reason why they withdrew into internal exile, and chose to publish in samizdat forums urging the recognition of individual moral rights and the constructivist theory of modern constitutionalism during the 1980s. They referred to the so-called ‘Helsinki Declaration’ (1975), the liberal theories of John Rawls,37 and Ronald Dworkin,38 and—after the transition—Arthur Danto’s postmodern aesthetics.39 Moreover, the famous member of the Polish opposition, Adam Michnik, was also an idol for them.

On the other hand, particularists believed merely in the determination of the special features of the Hungarian body politic, and—similarly to the representatives of the theory of communitarianism, but traditionally insisting on a discourse based in Hungarian intellectual history—they postulated that the national community inevitably mediates between individual freedom and human rights. Consequently, writers of that atelier sought to make the most out of possibilities given in the restricted publicity that was controlled from above, trying to push limits further and further. They often participated in open debates with the representatives of the dictatorship, provoking the arrogance of power. As a consequence, issues of journals were banned because of their writings. Instead of publishing in samizdat forums, they chose to dispute with editors appointed by the regime, fighting for free publication, or gave speeches at general meetings of the Hungarian Writers’ Association. This is the reason why they comprehended the Revolution as the manifestation of the joint effort of the body politic, when the particular community identified itself and woke up to self-awareness. The Revolution was the specific event for them when the genuine nation was constituted.

‘We have no choice but to assume joint responsibility of self-conscious intellectuals’

Essentially the two wings of the alternative Establishment that derived from the character of Hungarian history were contesting to justify the political authority of the newly founded community. Since cultural identity and political legitimacy are related to one another, the epistemological considerations of writers—e.g. their language and philosophical standpoint—were correlated with the adoption of the new political system and constitutional order. The latter phrase implies not only a text-based jurisprudence, but also a social practice. Hungarian democratization, the development of pluralism, and political identities may be described in this framework as the discourse of writers about the question of how to tell the history of the twentieth century focusing on 1956. Universalists typically preferred deconstructive criticism in literature and formal-justice-based but constructivist interpretation of the law in politics, the authoritative aspirations of logocentrism and material justice having been undermined. This phenomenon may have been a direct consequence of the given epoch, in which Western nation-states carried out the switch from ‘ethnocentric hegemony’ to ‘postcolonial discourse’. However, post-communist republics, having attained liberty, had to constitute the collective identity of the new body politic, which was actually relatively undisputed in the West. These intellectuals treated reality with radical scepticism on the level of metaphysical principles in their art. Their epistemological standpoint did not rely on hermeneutics, nor on the mimetic function of literature, and not— above all—on a stable ‘self’. Identity is merely ‘moving’ and just an ‘option’ for them.40

They would not continue the endeavour of previous centuries in pursuit of a stable identity, be it the identity of a person or of a community. According to this vision, the act of traditional storytelling has become outdated, in the case of persons as well as of communities. Every narrative is a kind of suppression; every identity is pressure. History is also a type of storytelling, a system of narratives and counter-narratives, and it is impossible to find the ‘master narrative’ among them. Besides this epistemological consideration, there are recognizable poetic consequences as well. Universalists additionally eliminate any appreciation of the poetic ego—because it allegedly has an essentialist character—in favour of the novel’s democracy without any particular point of view.41 Therefore, they postulate ironic utterance instead of pathetic voice. The expression of personal convictions is a rather naive and unreasonable strategy in their view. This is the reason why representatives of such a vision declined the offer of the historical moment, refrained from ascertaining common values—except for the neutral principle of pluralism—and the major components of the community’s self-determination. The customary rhetoric says that the poetic ego in the works of many poets, taken at the very heart of the sensual world, is invalid in ‘lyric democracy’, and contradicts the concept of Umberto Eco’s ‘open work’.42

On the other hand, the postmodern novels of Péter Esterházy, for instance, introduce a poly-perspective world with multiple centres. Novel is the demonstration of Kundera’s implications in the theory of art and of Richard Rorty’s pragmatism, irony, and ‘democratic hermeneutics’.43 For writers—in an ontological sense—‘things of reality’ are regarded as a set of textual signs, the connections built up among them deemed intertextual relations, without any moral consequences for everyday actions. If a constitution even has a ‘moral reading’, it is determined in the human rights-based jurisdiction. If novels or poems even have any identity-forming capacity, it is no more than the deconstruction of stable identity. Derrida is a frequent reference for that standpoint.44

The other group of intellectuals did not cultivate such a radical critique of language, and focused on social criticism instead. For them, general doctrines of human rights are necessary but not sufficient criteria in a democracy. Harking back to a merely traditional attitude of Hungarian literature, they have been reinterpreting the idiom of ‘nation’ as a metaphysical reality which has its own history beyond individual lives. In this broader philosophical sense, nation is not discriminatory, and does not postulate any sort of ethnocentric features; it does not even equate to a couple of unique abilities. The nation is a relatively uncertain system of values that operates as a cohesive, community-building power. Thus the fact must be emphasized that the nation does not transcend elemental oppositions or binary codes, because it is not an enemy of either discourse or pluralism. However, it has an indisputable, essential character that implies moral findings and socially committed ambitions. ‘Ethnos’ means neither a genealogical exclusion, nor an uncriticized, imagined profile of ancestry. In this sense, the modern ‘demos’ can be transformed into a democratic body politic if a given cultural tradition is internalized and criticized by political agents. Nation ensures a framework of actions; it does not imply prescriptions or obligatory decisions. This alternative intellectual strategy is striving to find out common narratives for the new body politic. History as the origin or ontological background of a constitution must be elaborated upon by writers and other artists. Key figures of that form of political participation were Zoltán Kodály, Gyula Illyés, László Németh, and Sándor Csoóri.

I must emphasize that every political action is derived from the zeitgeist, which is—in Hungarian history—manifested in the realm of art, principally in literature. The constitutional order and practice of 1989 were fundamentally based on the concept of formal justice. In the same manner, Hungarian literary criticism implemented the so-called ‘linguistic turn’ as an obligatory rule that belletristic materials, or the so-called ‘republic of letters’ do not affect the reality and the republic of men. The first philosophical trend originally refrains from giving positive answers to essential questions, so the decisions made in its internal system are difficult to undermine or even criticize.

However, insisting on the postulations of the latter trend, failures can easily be made. Albeit in the first case, writers are regarded as ‘literary professionals’, sealed within their own language, separated from ’politics’, in the latter case they are so much involved in the political system that it is made difficult for them to preserve their autonomous critical sense. The first strategy, the one of non-committal attitude, has failed historically, while the second, the one of committed intellectuals who feel responsibility for the community, should stand the test of time, although it is the matter of a single person’s moral courage. This is one of the Central European models that Scruton would accept in the sense of his formula: ‘The art and literature of the nation is an art and literature of settlement, a celebration of all that attaches the place to the people and the people to the place’.45 This statement has a specific connotation in Hungarian intellectual history, because we lived for a long time without real legal order or authority. The disequilibrium today is the outcome of the state’s declaration about the secularism and value neutrality of the post-ideological age.

However, this phenomenon entails reversing historical ‘ressentiment’ and other old patterns under the veil of—not ignorance—constitutional preferences. Law spirits away the limits between private autonomy and the public arena, and tends to provide the coherence of the many layers of law. It has become the only sphere that guarantees the common good, commonwealth, and common sense in the absence of religious norms and the moral reading of cultural texts. In the new communication platforms, the ability to foster practical reasonableness and grounded judgements of taste is being deteriorated. Our debates are mostly legalized or manipulated instead of topics being substantially discussed. Legalized debates result in litigation, and do not create tranquillity. The procedural and substantive conceptions of the rule of law used to collide within liberalism. Having experienced the weaknesses of liberalism, our dilemma is to avoid sheer decisionism and not to become doctrinaire. We have no choice but to assume joint responsibility of self-conscious intellectuals. Literary gentlemen or the man of letters should perceive and play their role not in the sense Karl Mannheim’s theory did, postulating a ‘free floating intelligentsia’46, but in a mere classical variant, let us put it this way: obeying conservative instinct.

Translated by Thomas Sneddon

NOTES

1 Roger Scruton, England and the Need for Nations (The Institute for the Study of Civil Society, 2006), 8.

2 Scruton, England and the Need for Nations, 24.

3 Scruton, England and the Need for Nations, 10.

4 Scruton, England and the Need for Nations, 29.

5 Scruton, England and the Need for Nations, 36.

6 Scruton, England and the Need for Nations, 35.

7 Scruton, England and the Need for Nations, 35.

8 Roger Scruton, Fools, Frauds and Firebrands: Thinkers of the New Left (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019).

9 Scruton, England and the Need for Nations, 27.

10 Russel Kirk, America’s British Culture (Routledge, 2017).

11 Kirk, America’s British Culture, 10.

12 Stanley Fish, Is There a Text in This Class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities (Harvard University Press, 1982), 324.

13 Fish, Is There a Text in This Class?, 330.

14 H. L. A. Hart, The Concept of Law (Oxford University Press, 1997).

15 Fish, Is There a Text in This Class?, 337.

16 John Finnis, Natural Law and Natural Rights (Oxford University Press, 2011), 134–144.

17 Finnis, Natural Law and Natural Rights, 147.

18 Finnis, Natural Law and Natural Rights, 148.

19 Finnis, Natural Law and Natural Rights, 150.

20 Quentin Skinner, The Foundations of Modern Political Thought. Volume One: The Renaissance (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

21 Skinner, The Foundations of Modern Political Thought, 89.

22 László Németh, A minőség forradalma I–VI. (The Revolution of Quality) (Magyar Élet, 1943).

23 Roger Scruton, Conservatism: An Invitation to the Great Tradition (All Points Books, 2018).

24 Jan Patočka, Plato and Europe (Stanford University Press, 2002).

25 István Bibó, ‘Az európai társadalomfejlődés értelme’ (The Meaning of European Social Development), Bibó István összegyűjtött munkái 1–4. (Collected Works of István Bibó) (Európai Protestáns Magyar Szabadegyetem, 1984), 560–637.

26 Jürgen Habermas, Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy (MIT Press, 1996).

27 János Erdélyi, A hazai bölcsészet jelene (The Present Situation of Hungarian Philology) (Sárospatak, 1857).

28 Alexander Bernát, ‘Irodalmi bajok’ (Literary Troubles), A Hét: Politikai és irodalmi szemle, 1890–1899 (The Week: Political and Literary Review) (Magvető, 1978), 22.

29 Yoram Hazony, The Virtue of Nationalism (Basic Books, 2018).

30 Jacob Burckhardt, Die Kultur der Renaissance in Italien (E. U. Seeman, 1908).

31 Stephen Greenblatt, ‘Towards a Poetics of Culture’, in H. Aram Veeser, ed., The New Historicism (Routledge, 1989), 1–13.

32 Robert M. Cover, ‘The Supreme Court, 1982 Term— Foreword: Nomos and Narrative’, Harvard Law Review, 97 (1983), 4–68.

33 Cover, ‘The Supreme Court, 1982 Term’, 4.

34 Jan Assmann, Das kulturelle Gedächtnis. Schrift, Erinnerung und Politische Identität in frühen Hochkulturen. (C. H. Beck, 1992). In Hungarian, A kulturális emlékezet. Írás, emlékezés és politikai identitás a korai magaskultúrákban (Budapest: Atlantisz, 2013), 80–88.

35 Milan Kundera, A Kidnapped West: The Tragedy of Central Europe (Harper, 2023).

36 Bibó-emlékkönyv I–II. (István Bibó’s Memorial Book) (Budapest: Századvég, 1991).

37 John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (Belknap Press, 1971).

38 Ronald Dworkin, Taking Rights Seriously (Harvard University Press, 1978).

39 Arthur C. Danto, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace: A Philosophy of Art (Harvard University Press, 1981).

40 Ernő Kulcsár Szabó, A zavarbaejtő elbeszélés (The Embarrassing Short Story) (Kozmosz Könyvek, 1984)

41 Mihály Vajda, A posztmodern Heidegger (The Postmodern Heidegger) (Osiris, 1993).

42 Umberto Eco, The Open Work (Harvard University Press, 1989).

43 Richard Rorty, Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (Cambridge University Press, 1989).

44 Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology (John Hopkins University Press, 1976).

45 Scruton, England and the Need for Nations, 16.

46 Karl Mannheim, Ideology and Utopia: An Introduction to the Sociology of Knowledge (Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1966).

Related articles: