This article was originally published in Vol. 5 No. 1 of our print edition.

War is upon us. Land war in Ukraine. Civil war in Israel, even with an interregnum via the ceasefire agreement. Both of these conflicts threaten to expand into regional wars. China continues to rattle its sabre over Taiwan. The so-called liberal world order, a unipolar system overseen by the United States, is crumbling as American hegemony weakens, increasing the threat of multiple regional conflicts.

The breakdown of the liberal system raises questions we have not had to answer since the early 1990s. Three decades of American dominance since the fall of the Soviet Union have meant that theorists, scholars, and practitioners emphasized peace rather than war. International relations theory has been marked by idealism and ‘peace studies’, and relations between nations saw an inordinate focus on economic rather than military diplomacy.

Christian thinkers have been no different in this regard. The muscles that had been exercised constantly prior to 1990 have atrophied in the neoliberal era. We need to revisit a Christian approach to thinking about the relations between nations and about war.

War in Christian Thought

There have been, broadly, two ways of approaching the problem of war in the Christian tradition. One way looked at war as an ethical problem. Thinkers directly addressed the issue of killing in war as a moral dilemma. For instance, Jesus Christ is depicted in Luke 3 as telling soldiers to do no wrong and to be content with their pay. It is notable that our Lord never told the soldiers he was addressing to forego their vocations and put down their weapons. We see a similar indifference to military involvement in the writings of the Patristic father, Tertullian (c. 155–c. 220). In his ‘The Military Chaplet’, the primary concern is not killing or the coercive nature of military life, but rather the dual allegiance that a Christian who is an Imperial solider has to deal with. ‘Shall he’, writes Tertullian of the soldier, ‘carry a banner in rivalry to Christ’s?’ Tertullian’s practical answer to the dilemma raised by the conversion of a soldier is to ‘keep clear of official responsibilities [to] avoid occasions for sin’.1

‘Niebuhr’s anthropological pessimism provides a foundation for his notion that nations can, and should, work towards a fragile justice’

The other approach to the problem of war offered by the Christian tradition addressed the issue of relations between kingdoms and the possibility of war. This line of discourse birthed ‘just war’ theory, which was articulated through the writings of two of the giants of Western Christendom, Augustine of Hippo (354–430) and Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274). There is no particular need to delve into this complex territory, as it is well mapped. Suffice it to say that the mainstream Western Catholic position on war is that it can be justified and, at times, ought to be undertaken. John Calvin (1509–1564), for instance, argues as much in his pointed polemics against his Anabaptist contemporaries. ‘Kings and people must sometimes take up arms to execute public vengeance’, writes Calvin, because ‘power has been given to them to preserve the tranquillity of their dominion’.2 Natural law lays the grounds for nations to defend themselves against external threats: ‘Princes must be armed not only to restrain the misdeeds of private individuals…but also to defend by war the dominions entrusted to their safekeeping.’3 The Apostles said nothing about this, according to Calvin, because ‘their purpose was not to fashion a civil government, [but rather] the spiritual Kingdom of Christ’.4 Apostolic silence does not equal Christian pacifism.

Nor does apostolic silence mean that there are no Christian principles, whether theological or philosophical, that we can reason from when it comes to relations between nations. In the brilliant nineteenth book of City of God, Augustine lays out some basic realities that ought to undergird a Christian vision of international order and disorder. In short, he writes that human society, from the household up to the realm of international relations, is marked by misery. Human discord occurs at an international level due to the diversity of peoples and tongues, such that ‘a man would more readily hold a conversation with his dog than with another man who is a foreigner’.5 Is there a solution to this discord? One, which the pax Romana exemplified, is war. ‘How many great wars, what slaughter of men, what outpourings of human blood have been necessary’ to bring about peace.6 Yes, Augustine says, war is a misery. And yet, war is necessary and can be just because it brings about peace and order in a world marked by human sin and disorder. ‘Wars themselves’, writes Augustine, ‘are conducted with the intention of peace…, it is clear that peace is the desired end of war’.7 War makes peace. Because of fallen human nature, war is necessary for peace.

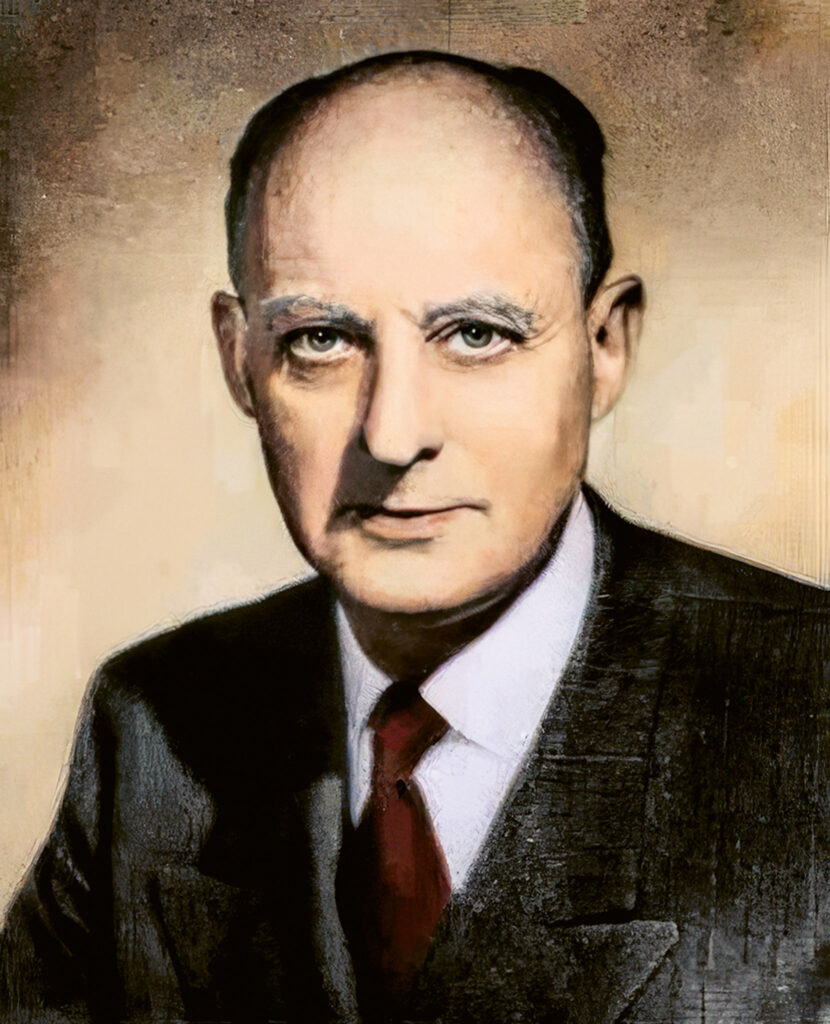

Augustine’s framework for understanding the relationship between sinful human nature and the inevitability of human conflict at all levels of community was analysed by the Protestant thinker Reinhold Niebuhr (1892–1971). In his essay on Augustine’s realist outlook, published in his 1953 book Christian Realism and Political Problems, Niebuhr unpacks the late Bishop of Hippo’s anthropology as it relates to politics. Niebuhr defines ‘realism’ as ‘the disposition to take all factors in a social and political situation which offer resistance to established norms into account, particularly the factors of self-interest and power’.8 In opposition to the great Greek thinkers of antiquity, who held that when reason reigned, so too would good order, Augustine painted a different picture. According to Niebuhr, Augustine ‘gives an adequate account of the social factions, tensions, and competitions which we know to be well-nigh universal’ in human communities.9 Human self-love, or ‘egocentricity’, undergirds the fraught nature of human relations. This leads Augustine to describe life in the ‘civitas terrena’ as, in Niebuhr’s words, ‘constantly subject to an uneasy armistice between contending forces’.10

Niebuhr further notes that Augustine’s assessment of human nature tames any optimism or idealism about the possibility of a peaceful supranational community. ‘The world’, according to Augustine, ‘is all the more full of perils by reason of its greater size’.11 According to Niebuhr, Augustine’s realism acknowledges that the ‘common linguistic and ethnic cultural forces’ are, at the level of world community, ‘divisive’ and should give pause to anyone who envisages any kind of world government. Here we find Niebuhr gesturing towards the ramifications of Christian realism for international relations and for our understanding of war. As intellectual historian Matthew Anderson correctly notes, Niebuhr was a complex Christian realist who remained interested in the possibilities for an international order leading to peace.12 Nevertheless, Niebuhr’s thought constitutes an intriguing attempt to frame a Reformed- and Augustinian-imbued approach to international relations. One key plank for Niebuhr’s realism is his critique of certain kinds of Christian pacifism, which he provocatively called a ‘heresy’.

Pacifism as Heresy

As with all heresies, the very definition of Christianity is at stake in Niebuhr’s framing of pacifism. Christianity is not ‘primarily a “challenge” to man to obey the law of Christ’, but is rather ‘a religion that deals realistically with the problem presented by the violation of this law’.13 The problem is man’s sinfulness, his fall from perfection, and the need to be rescued from the results of this fall. For the perfectionist who chooses pacifism, the problem is a lack of will to obey the law of love that Christ proclaims. It is true enough that every Christian, and every human person, is morally obliged by the law of Christ. But the problem that Niebuhr identifies is the fixation of certain Christians on obedience to this law. They frame this as the solution to man’s moral and spiritual quagmire. If people simply loved more, man’s condition would be righted, and peace would reign in social and political settings across the world.

The problem is, as Niebuhr points out, this simply is not true about man or Christianity. Christianity solves the problem of human sin by God’s intervention in history through the incarnation, death, and resurrection of the second person of the Godhead. To cite Niebuhr again, Christianity deals ‘with the problem presented by the violation of [God’s] law’. Salvation is of the Lord, not of man. Crucial to this discussion is the second aspect of the pacifist heresy: anthropology. Pacifists have, according to Niebuhr, ‘absorbed the Renaissance faith in the goodness of man, have rejected the Christian doctrine of original sin…have reinterpreted the cross [to mean that] perfect love is guaranteed a simple victory over the world, and have rejected all other profounder elements of the Christian gospel as “Pauline” accretions which must be stripped from the “simple gospel of Jesus”.’14

Because of this anthropological optimism, pacifists are prone to political utopianism. Man can be good and is fundamentally good, and therefore, if we fix the conditions of man’s existence, justice can be realized. This is folly, according to Niebuhr. There is a correct impulse here, where the pacifists refuse to ‘allow the political strategies, which the sinful character of man makes necessary, to become final norms’.15 The error, which is a grave one, comes in the impulse to extend this belief into the realm of political strategy, such that obedience to Christ’s law of love becomes a legitimate alternative to political strategies that aim at imperfect and fragile justice in our fallen world.

Niebuhr’s critique of this view is that it does not match with the biblical view of man, and nor does it accord with reality. According to Niebuhr, the heretical pacifist believes ‘that if you can abstract the rational-universal man from what is finite and contingent in human nature’, or cultivate the ‘mystic-universal’ part of man’s consciousness in the right direction, ‘you will be able to eliminate human selfishness and the consequent conflict of life with life’.16 However, this view of human nature is untrue, conforming ‘neither to the New Testament’s view [nor to] the complex facts of human experience’.17 The heresy lies in the substitution of ‘faith in man for faith in God’.18 The folly lies in the lack of correspondence with reality. ‘If we believe’, says Niebuhr, ‘that if Britain had only been fortunate enough to have produced 30 per cent instead of 2 per cent of conscientious objectors to military service, Hitler’s heart would have been softened…we hold a faith which no historic reality justifies’.19

Pacifism is not a tenable position for the Christian in this case for the reasons outlined. Put another way, pacifism of the kind Niebuhr attacks is not really Christian. We can have our behaviour governed by the law of Christ and yet still reckon with the realities of living in this fallen world. It is the precision and purity of the heretical pacifist that troubles Niebuhr, not the desire to live according to the ethic of the Sermon on the Mount. The heretic will find, says Niebuhr, that ‘an ethic of pure non-resistance can have no immediate relevance to any political situation; for in every situation it is necessary to achieve justice by resisting pride and power’.20 The law of love preached by Christ cannot ultimately be fulfilled by the pacifism Niebuhr critiques because the ultimate goal of the law is justice. In a world riven by conflict and hatred, Niebuhr rightly maintains that heretical pacifism is no ‘alternative for the conflicts and tensions from which and through which the world must rescue a precarious justice’.21 Humans are as they are, and sin is still universal and prevalent in this present age, so justice and peace must be rescued via a realistic vision of people and nations.

Niebuhr’s Christian Realism and International Relations

Niebuhr did not leave his discussion of Christian realism about morality and justice at the level of the individual. He was a prominent public intellectual during the interwar era, the Second World War, and the Cold War. Judging by his corpus of writings, one of his most intense interests was the ethical understanding of the relations between nations. Niebuhr was interested in international relations, in part because his context demanded it. He wrote extensively on the possibility and problems of world community, the history and moral responsibility of the United States, and the nature of democracy. He wrote an abundance of short articles on particular conflicts, the peace negotiations after the Second World War, and the moral hazards that followed that war for the victors.

Niebuhr lived in a world dominated by war and the possibility of war. This is why his thinking is a helpful foil for our naive, idealistic, unipolar age of peace. As a Reformed Christian, Niebuhr believed in the moral responsibility of people and nations. He also believed that the relations between people and nations are inherently fraught, and therefore, war is sometimes necessary. The international relations theorist John Mearsheimer calls Niebuhr’s brand of realism ‘human nature realism’. For instance, the influential jurist Hans J. Morgenthau argued, along with Niebuhr, that the moral side of human nature is crucial for understanding the actions and motives of nations and their leaders. Mearsheimer further argues that thinkers like Niebuhr and Morgenthau operated on ‘the simple assumption that states are led by human beings who have a “will to power” hardwired into them at birth’.22 Because of this will to power, states are constantly striving for supremacy, which results in regular jostling that often takes the form of military conflict.

Unlike Mearsheimer, who does not frame relations between nations through a moral lens, Niebuhr argues that nations are moral entities. Their morality, or more often their immorality, is founded on the human nature of the people that compose the nation. ‘The selfishness of nations is proverbial’ according to Niebuhr.23 Their actions are driven by greed and ‘egoism’. The egoism of the individual works itself out in the egoism of the nation, by which Niebuhr means that nations are driven by the need to assert themselves upon the international stage through conquest, empire, and economic achievement. Niebuhr is most acutely concerned with the unwieldly nationalism of the early twentieth century when he discusses the moral character of nations and suggests that ‘neither religious nor rational idealism’ can find a way to subjugate national egoism.24

Nations are also hypocritical. They lie, justifying their actions through moral posturing that has no basis in reality. Niebuhr’s example is the way German intellectuals during the Great War clothed ‘national aspirations…in the attributes of universality’.25 Thinkers like Adolf Harnack, Rudolf Euken, and M. Paul Sabatier deployed ‘the force of reason…only to give the hysteria of war and the imbecilities of national politics more plausible excuses than an average man is capable of inventing’.26 German aggression was clothed in the garments of defending and expanding the goods of European civilization. Justifications of American expansionism, better phrased as ‘American Empire’, provide a more recent example of this kind of hypocrisy. Invasions and military interventions based on the spreading of universalistic ideals of democracy and freedom have underpinned the foreign policy of the United States over the past thirty years. Perhaps we could say some similar things about the British Empire, although the goods that arose from British colonialism are more obvious and substantial than those of America’s imperial adventures.

Given this egoism and hypocrisy, does Niebuhr hold out any hope for international peace? He suggested in the early 1930s, before the cataclysm of the Second World War, that ‘the best that can be expected’ is that nations might begin to ‘justify their hypocrisies by a slight measure of real international achievement’.27 By this, he was pointing to the possibility of nations co-operating at a supranational level to bring about order from anarchy. Niebuhr hoped that they might ‘learn how to do justice to wider interests than their own, while they pursue their own’.28 However, his conclusions about nations were pessimistic. Nations are ‘too selfish and morally too obtuse and self-righteous to make the attainment of international justice without the use of force possible’.29 A League of Nations, or a United Nations, has the potential to bring about a semblance of order. Yet, even this will be limited and temporary due to the ‘will-to-power of individual nations’.30 Motions towards supranational unity needed to be organic and motivated by national interest, according to Niebuhr. He concedes that Thomas Hobbes was partly right. A unity based around coercion, a ‘world government’, would be nothing but tyranny; nations need to come together voluntarily and give up their interests for their own interests.31 But they will not. War will continue. Conflicts will abound. We can hope for international order, but there is little that grounds this hope.

Conclusion

Applying Christian theology and ethics to international relations is now an acutely important activity. The hopeful realism of Reinhold Niebuhr offers one way of recovering a Christian approach to the crisis that is hurtling towards our civilization at a terrifying speed. Niebuhr’s anthropological pessimism provides a foundation for his notion that nations can, and should, work towards a fragile justice. However, this justice will always be temporary, and any perceived ‘order’ of nations will be no more than a figment of one’s imagination. To use his words that describe Augustine’s social theory, Niebuhr believed in, at best, an uneasy armistice between nations. Niebuhr’s view of human nature, partially influenced by Augustine, led him to emphasize the self-love and self-interest of nations that act in the world upon the whims and egoism of their people. Furthermore, nations are readily deluded. They regularly frame their realpolitik in terms of universal ideals, a self-deception that can easily lead to disaster and escalation to war.

The best we can hope for is a temporary peace. That peace is the peace of the saeculum, the present age, the time of waiting that Augustine so powerfully articulated. Niebuhr’s variety of Christian realism is grounded in a philosophy of history as much as it is upon anthropology. The current age is a fallen one, marred by sin, coloured indelibly by human selfishness. Nations are affected by this as much as any other institution, a reality that ought to leave a deep impression on our thinking about international relations. At the same time, those same nations, and the people who lead them, have obligations to confront evil and seek to preserve peace and justice. This seems like a call to spread democracy and fight for the cause of freedom. But it is not. It is a call to seek peace between nations with prudence, which sometimes requires war. Ultimately, Niebuhr offers a Christian way of facing the flawed and fraught realities of geopolitics and the politics of great powers.

NOTES

1 Tertullian, ‘The Military Chaplet’, in Oliver O’Donovan, and Joan Lockwood O’Donovan, eds, From Irenaeus to Grotius: A Sourcebook in Christian Political Thought (Eerdmans, 1999), 27–8.

2 John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, 2 vols, translated by Ford Lewis Battles (Westminster John Knox, 1960), book 4, chapter 20, section 11 (4.20.11).

3 Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion.

4 Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, 4.20.12.

5 Augustine of Hippo, The City of God against the Pagans, translated by R. W. Dyson (Cambridge University Press, 1998), book 19, section 7 (19.7).

6 Augustine, City of God against the Pagans.

7 Augustine, City of God against the Pagans, 19.12.

8 Reinhold Niebuhr, ‘Augustine’s Political Realism’, in Robert McAfee Brown, The Essential Reinhold Niebuhr: Selected Essays and Addresses (Yale University Press: 1986), 123.

9 Niebuhr, ‘Augustine’s Political Realism’, 123.

10 Niebuhr, ‘Augustine’s Political Realism’, 127.

11 Augustine, City of God against the Pagans, 19.7.

12 Matthew Anderson, ‘The Myth of Reinhold Niebuhr’s Political Realism’, Centre for Intellectual History Blog, https://intellectualhistory.web.ox.ac.uk/article/the-myth-of-reinhold-niebuhrs-political-realism.

13 Reinhold Niebuhr, ‘Why the Christian Church Is Not Pacifist’, in McAfee Brown, 103.

14 Niebuhr, ‘Why the Christian Church Is Not Pacifist’, 104.

15 Niebuhr, ‘Why the Christian Church Is Not Pacifist’, 104.

16 Niebuhr, ‘Why the Christian Church Is Not Pacifist’, 105.

17 Niebuhr, ‘Why the Christian Church Is Not Pacifist’.

18 Niebuhr, ‘Why the Christian Church Is Not Pacifist’.

19 Niebuhr, ‘Why the Christian Church Is Not Pacifist’.

20 Niebuhr, ‘Why the Christian Church Is Not Pacifist’, 107.

21 Niebuhr, ‘Why the Christian Church Is Not Pacifist’, 119.

22 John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (Norton, 2014), 19.

23 Reinhold Niebuhr, ‘Moral Man and Immoral Society’, in Elisabeth Sifton, ed., Reinhold Niebuhr: Major Works on Religion and Politics (Penguin Random House, 2015), 210.

24 Niebuhr, ‘Moral Man and Immoral Society’, 218.

25 Niebuhr, ‘Moral Man and Immoral Society’, 220.

26 Niebuhr, ‘Moral Man and Immoral Society’.

27 Niebuhr, ‘Moral Man and Immoral Society’, 228.

28 Niebuhr, ‘Moral Man and Immoral Society’.

29 Niebuhr, ‘Moral Man and Immoral Society’, 229.

30 Niebuhr, ‘Moral Man and Immoral Society’, 230.

31 Niebuhr, ‘The Myth of World Government’, in Sifton, ed., 664.

Related articles: