In the spring of 1792, the French National Legislative Assembly adopted the guillotine as a means of execution. But the guillotine was not only used to execute historical figures such as the French King Louis XVI, Danton and Saint-Just. The guillotine also became a symbol of revolutionary violence and terror, which unfolded with Robespierre’s “mystical” change of heart during the years of the French Revolution.

In school studies and in the public consciousness, the events of the French Revolution are most often associated with the ideals of liberty and equality, and with the struggle for civil rights and against tyrannical power. But the reality was much more disappointing and brutal: it is no coincidence that less than a decade after the adoption of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in 1789, Napoleon was able to orchestrate a coup and impose a military dictatorship.

As an example of the escalation of violence, the guillotine alone claimed the lives of more than 10,000 people.[1] The historian Reynald Secher estimates that almost 5,000 people were drowned in the last months of 1793 alone (including priests, children and women), and some 50,000 more were executed by other means or died in prison because of the poor conditions. Between 23 Prairial and 8 Thermidor, at the height of the Revolution, the Revolutionary Tribunal handed down 1,285 death sentences, but the number of people in prison kept rising. On 23 Prairial, 7321 people were registered; on 10 Thermidor, 7,800. ‘Batch after batch was sent to the guillotine in rapid succession,’[2] wrote the historian Mathiez.

The civil war between the royalists and the republicans became particularly fierce in the rural regions, with hundreds of thousands of people dying as the two sides fought:

‘Logic itself says that the crueller of the two sides was the one that believed it was avenging God, that sought to match unlimited suffering with unlimited crime. In shedding blood, the republicans did not have such an exalted vision. They wanted to suppress the enemy, nothing more; their firing squads and their drownings were means of shortening death and not human sacrifices,’[3] Jules Michelet wrote later, trying to justify the terror.

But what led to this terrible massacre, when the first period of the French Revolution seemed so idyllic, at least in terms of certain events?

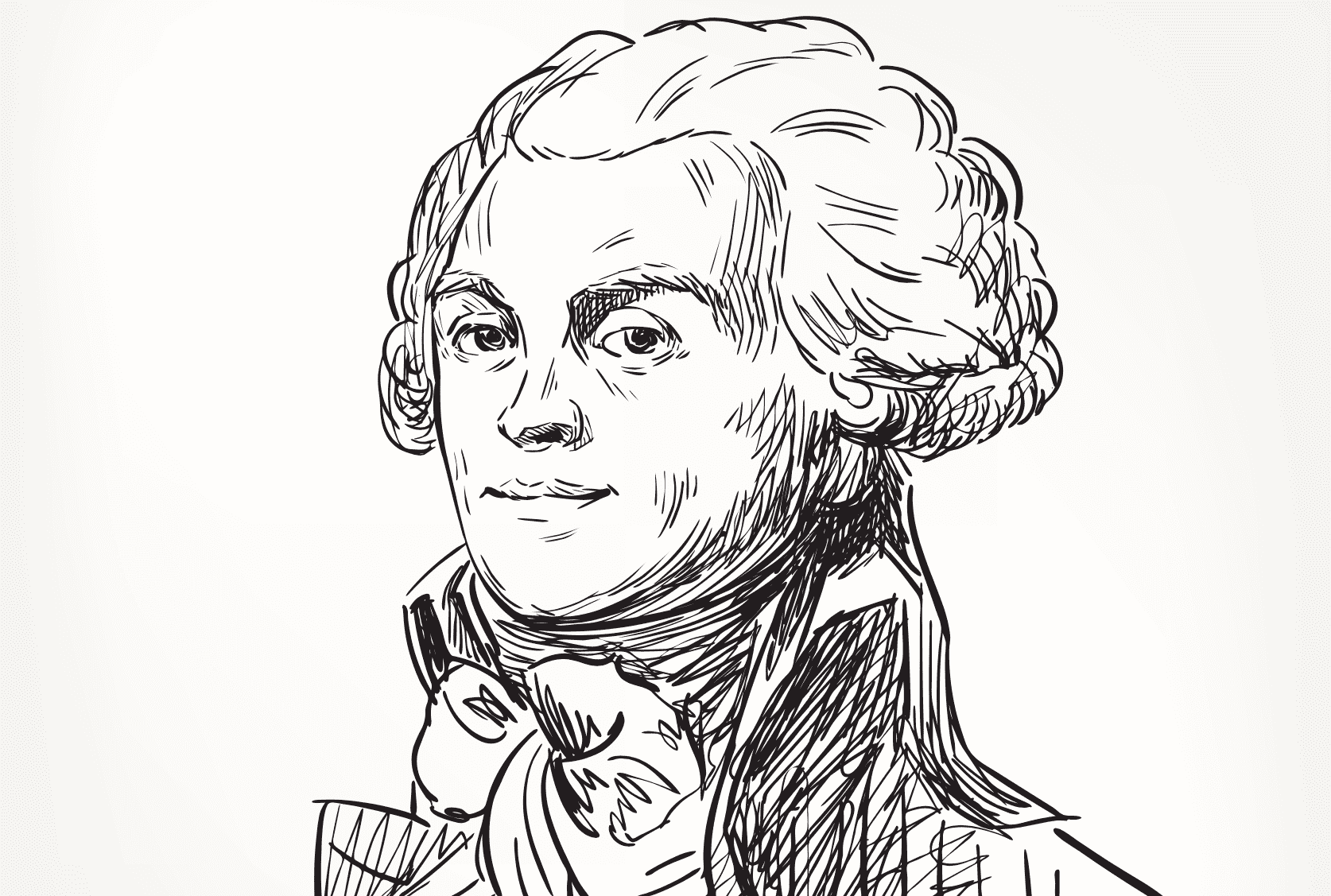

To answer this question, it is worth looking at the political turnaround of Maximilien de Robespierre.

‘My heart is true…’

‘For nearly thirty years now, since long before I became a professional historian, I have been haunted by a question: what led a man like Robespierre (and others like him) –a man who at the start of the Revolution was a humanitarian opposed to the death penalty– to choose terror four years later?’[4] historian Marisa Linton asked about one of the most fascinating questions of the French Revolution.

Until the beginning of the French Revolution, some historians described Robespierre as a kind of éminence grise. According to Norman Hampson’s portrayal, Robespierre was a diligent and ambitious person, unafraid of hard work and characterised by moderation. Before 1789, there were no signs that Robespierre would later become a radical politician.[5] As with his contemporaries, Robespierre was characterised by his adherence to democratic and liberal principles. His political career began at the same time as the French Revolution, and he was 30 years old when the citizens of Arras elected him as a deputy in March 1789. His speeches succeeded in attracting attention to himself.

Maximilien Robespierre’s Reign of Terror aimed at nothing less than the eradication of Christianity

His father was a lawyer, so it is no wonder that Robespierre focused his work on the legislative process in the National Assembly. He welcomed the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, supported universal suffrage, opposed the abuse of power–by the monarchy–and discrimination on religious and racial grounds. Robespierre was in favour of making the Papal estate of Avignon part of France (there is some debate about whether or not Robespierre was radically anti-Christian (or anti-Catholic?). ‘Reminiscent of the Great Persecution unleashed by the Roman Emperor Diocletian at the outset of the fourth century, Maximilien Robespierre’s Reign of Terror aimed at nothing less than the eradication of Christianity. And yet, the Jacobin Cult of the Supreme Being infused society with hymns, prayers, and festivals modeled on Christian liturgy,’ Manfred B. Steger noted about Robespierre’s later role. [6]

So Robespierre did take radical–and progressive–positions at the time, but initially there was no trace of him endorsing violence and terror. ‘My heart is true and my resolution strong. I have never borne the yoke of baseness and corruption. If there is anything with which I am to be reproached it is that I have never been able to disguise my way of thinking, that I have never said “Yes” when my conscience cried out “No,” that I have never courted the potentates in my country,’[7] was the political ars poetica of Robespierre.

‘A fanatic of an ideal’

The great changes in Robespierre’s political action took place between 1791 and 1793, and the trial of King Louis XVI in particular marked a turning point. Robespierre initially expressed serious reservations about violence, arguing that it was a contradiction in terms to use the same means to secure liberty as despotic power used against liberty. In the trial of the king, however, Robespierre said: ‘To what sentence shall we condemn Louis? The death penalty is too cruel. No, says another, life is crueller still: I demand that he live. Advocates for the king, is it from pity or cruelty that you want to shield him from the penalty for his crimes?…I myself abhor the death penalty generously prescribed by your laws; and for Louis i feel neither love nor hate, i just hate his crimes…Yes, the death penalty, in general, is a crime, and for the sole reason that, in keeping with indestructible principles of nature, it can only be justified where it is necessary for the security of individuals or the social body…I utter this deadly truth with regret, but Louis must die, because the homeland has to live…I ask that this memorable event be commemorated with a monument to nourish in the hearts of peoples the sense of their rights and horror of tyrants; and in the minds of tyrants, salutary terror of the people’s justice.’[8]

From then on, for Robespierre, terror became a centralised principle of government, designed to promote political ends effectively. He had already accepted the crackdown on the enemies of the revolution, but his attitude to the violence of terror gradually became more and more sacralised from this point onwards, almost until his death. This reign of terror was, however, a contradiction in terms, since Robespierre and his comrades were in theory promoting political freedom and religious freedom.

Many historians have therefore drawn parallels between the events of the French Revolution and the Russian (Bolshevik) Revolution, noting that in certain phases of the French–civil– revolution the violence was even more brutal than in the Russian Revolution.[9] As early as 1938, Fritz Hirschner saw parallels between Robespierre’s and Stalin’s reigns of terror, although he also stressed the main differences: ‘A tyrant sits within the walls of the Kremlin, long surrounded by a circle of fear and isolation. He is not, however, a fanatic of an ideal, like Robespierre, but increasingly a ruthless fanatic of his own ego, who eradicates what seems dangerous to his suspicions, which have grown into madness.’[10]

The progressive violence

Unlike Stalin, Robespierre was indeed a fanatic of the ideal: ‘It is time to state clearly the goal of the revolution, and the conclusion we want to reach; (…) What is the goal we are aiming for? Peaceful enjoyment of liberty and equality; the reign of that eternal justice whose laws are engraved, not in marble and stone, but in the hearts of all men, even of the slave who forgets them, and the tyrant who denies them,’[11] Robespierre declared in February 1794, years after the revolution had broken out (and a few months before his death).

‘The guillotine no longer comes crashing down by order of God and King,’ but ‘the people’ use violence

Robespierre became increasingly obsessed with terror in order to achieve his ideological goals. He wanted to achieve a moral society, a “state of virtues,” and to sweep aside everything that stood in the way of what he believed to be its realisation. According to Michael Blain’s analysis, from an etymological point of view, terror can be divided into three periods: pre-revolutionary, revolutionary and post-revolutionary terror. The revolutionary violence (revolutionary terror) can be identified with Robespierre and his system of “the Reign of Terror”. In this case, ‘the guillotine no longer comes crashing down by order of God and King,’ but ‘the people’ use violence. ‘Terrorism is the name applied to illegitimate and criminal, political violence by liberal governmental regimes in societies originally constituted by revolutionary violence.’[12]

Terror thus has two value judgements, from a liberal point of view terror can be good, terror can be “progressive” as it can serve to create a better society according to idealists. In contrast, the “conservative” –reactionary–interpretation of terror is that it is bad, reprehensible: ‘What distinguishes the French Revolution and what makes it an event unique in history is that it is radically evil; no element of good relieves the picture it presents; it reaches the highest point of corruption ever known; it is pure impurity… Only the evil genius of Robespierre could achieve this miracle,’ stated Joseph de Maistre in 1796.

Robespierre, on the other hand, did not see terror as merely necessary (positive), but as central to his political ideology: ‘…the principle of our Republic is this: to influence the people by the use of reason, to influence our enemies by the use of terror… In times of peace, virtue is the source from which the government of the people takes its power. During the Revolution, the sources of this power are virtue and terror: virtue, without which terror will be a disaster; and terror, without which virtue is powerless. But terror is nothing more nor less than swift, severe and indomitable justice.’[13]

In the end, Robespierre could not escape his fate and became a victim of the terror he introduced and then unleashed. It is symbolic that Robespierre and his companions were sentenced to death by the severe justice without a fair trial and without a verdict, which was implemented by guillotine in July 1794.

[1] Evan Andrews, ‘8 Things You May Not Know About the Guillotine,’ History.com, 2014, https://www.history.com/news/8-things-you-may-not-know-about-the-guillotine, accessed 28 Feb, 2022.

[2] Albert Mathiez, The French Revolution, London, Williams and Norgate, 1927, p. 499.

[3] Reynald Secher, A French Genocide. The Vendée, Notre Dame, University of Notre Dame, 2003, p. 259.

[4] Marisa Linton, Choosing Terror, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013, p. VII.

[5] David P. Jordan, ‘Robespierre,’ The Journal of Modern History. Vol. 49, No. 2 ,1977, p. 284.

[6] Manfred B. Steger, The Rise of The Global Imaginary, Political Ideologies from the French Revolution to the Global War on Terror, Oxford, New York, Oxford University Press, 2008, p. 21.

[7] Jean Matrat, Robespierre: The Tyranny of The Majority. New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1971, p. 44.

[8] Slavoj Zizek, Robespierre: Virtue and Terror, London, Verso, 2017, p. 144.

[9] Arno J. Mayer, The Furies. Violence and Terror in the French and Russian Revolutions, New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 2000, p. 102.

[10] Fritz Hirschner, ‘Stalin und Robespierre: Eine historische Parallele,’ Zeitschrift für Politik, Vol. 28, No. 4, 1938, p. 240.

[11] Zizek, Robespierre, p. 201.

[12] Michael Blain, Angeline Kearns-Blain, Progressive Violence, London-New York, Routledge, 2018, p. 68.

[13] Thomas E. Hachey, Ralph Weber, Voices of the Revolution. Rebels and Rhetoric, Hinsdale, The Dryden Press, Hinsdale, 1972, p. 17.